After 90s FMV drove head-long into the wall of reality, Trilobyte Games had a lot of trouble making a sequel to their seminal title, The 7th Guest. There were a few re-releases to the original game, generally passing over The 11th Hour, but that was it. In 2013 they attempted to crowdfund for The 7th Guest 3: The Collector, but failed twice. Ironically, it was Kickstarter that would give the series its next kick, as an officially-approved fan game by indie studio Attic Door Productions made its smaller target it 2015. The result would be The 13th Doll, which hit digital shelves amid a resurgence for FMV games headed by Her Story and more. But where other, modern FMV titles were ready to use improved technology, file sizes and acting to push the former dead-end medium in a new direction, The 13th Doll was ready to look backwards, not in parody, but as a loving, detailed tribute to a very specific era of gaming, warts and all. In fact, warts especially.

The 13th Doll is set quite a few years after the chronologically wobbly ending of The 7th Guest. Tad, the titular seventh guest, has escaped Henry Stauf’s mansion, but has been dubbed insane by his stories of ghosts and the mental health standards of the day. When a certain Dr. Richmond takes over the asylum where Tad is held, his revisionist policies lead him to take Tad on a trip to the Stauf Manor for some exposure therapy. Tad however, guided by a ghostly woman in white, escapes and both characters head to the mansion independently. The player is allowed to follow either character in their journey through the mansion and its surrounds, each storyline with its own unique puzzles and challenges.

Controls are much like you’d expect from the previous games in the series. Walking speed is somewhere in between The 7th Guest‘s original sloth-crawl and The 11th Hour‘s zooming from place to place, maybe still too fast to be atmospheric but certainly not slow enough to be obnoxious. Similar to Myst V, The 13th Doll allows you to use either node-based movement or free movement in the real-time 3D environments, though since the game smaller environments than Myst V, free movement isn’t the clear winner this time. While walking, the player can find the old “chattering teeth” animations (just as corny as ever), as well as various 3D objects to examine just to bring life to the house. The game encourages further exploration with two collection side-quests tied to achievements: teeny gold coins refering are everywhere, and you can also find cleverly-integrated names of major Kickstarter backers, disguised as signatures and bylines. While the game doesn’t feature the talents of George “The Fat Man” Sanger on music, the soundtrack is fairly strong, with a unique track for every puzzle.

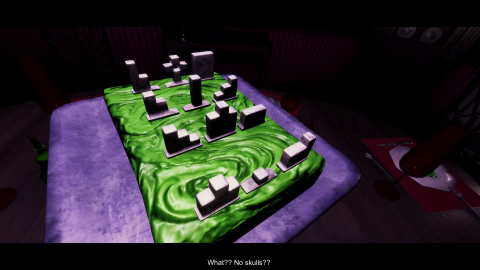

Of course, the centerpiece of the game are those puzzles. Between Tad and Richmond, there are slightly more puzzles than the previous games, a little over two dozen. Of course, The 13th Doll was released in a very different market than the its predecessors: the Trilobyte titles had in the neighborhood of two dozen puzzles as well, but the high-quality Professor Layton games offer hundreds, and low-end puzzle collections can be purchased off Steam for pennies. To keep up the modern pace while maintaining the same feel as the Trilobyte games, The 13th Doll would have to be tough as nails, and most of the puzzles keep up, even if it means being obtuse or unfriendly. In fact, the game seems determined to homage some of the worst puzzles of the past: AI-driven board game puzzles, an unnecessarily large underground maze, with a map found elsewhere in the mansion, and a new piano puzzle too. There’s also an homage to the opening cake puzzle from The 7th Guest, and it’s pretty rough, too. If you need a hint, The 13th Doll is generous enough to provide immediate instructions for each puzzle, and hints only require a short cooldown. The end result is arguably par with the previous games, though the period-appropriate frustrations won’t be for everyone. On the plus side, the game offers excellent colorblind and hard-of-hearing support for its puzzles, but its closed captions are riddled with typos and timing errors.

Speaking of period-appropriate, the FMVs are here to entertain. Tech limitations from back in the day are emulated through modern trickery. The game’s happy to show this off in the opening few minutes. The camera passes through a door backwards, there is a brief pause as the game swaps 3D sets… and a completely different style of door appears in its place. When Richmond looks into Tad’s cell, he finds a flat FMV not an inch from the window, barely feigning depth. Child characters are performed by undisguised adults. The story as a whole is as janky as The 7th Guest, though that approach might not be a positive. Still, the game reminds of other high-quality salutes to low-quality pasts, like Garth Marengi’s Darkplace. The acting is the trickiest bit: it’s hard to feign such a highly specific slice of 90s amateur acting that made the Trilobyte games what they were, and as a result, The 13th Doll‘s acting feels more like its own thing. The script is also full of references that none of the actors, not even Hirschboek, seem to be trying to emulate. Obnoxiously, the game won’t allow you to skip most custscenes.

In addition to the new cast, Robert Hirschboeck returns as Stauf, and is just as great as ever. His antagonist role isn’t universal, however: he and the ghostly woman in white are in competition, with Stauf trying to control Dr. Richmond and the woman trying to control Tad. As a result, they only taunt the opposite character during puzzles. Unfortunately, both sets of taunts are just sort of annoying, as they’re shared in common across the entire puzzle set and will quickly run out.

Besides the puzzles, each player character is expected to collect a number of items from the environment: Richmond is collecting parts for a machine that Stauf wants constructed, while Tad is assembling the titular 13th Doll. These are a little less meticulously hidden than the coin and donor names from the original game, and are thankfully marked on the map if you miss them. Once these are found, the player can choose from multiple endings per character, after which they can return to the game for the newly-unlocked graveyard, which includes the final collectibles and the game’s optional bonus puzzle, a “versus” puzzle against the AI which is arguably too easy. It only makes sense the developers banished to limbo like this considering you might solve it in seconds, but it’s nice to find all the same. This isn’t the only secret. Entering the mysterious number from the TV show Lost, of all things, will also unlock a weird, sepia-esque filter and free access to the mansion with both sets of puzzles. The toughest secret is the secret ending, which arguably alludes to The 11th Hour: to get it, you have to go through both storylines, see every ending, and solve each puzzle without using a hint at least once. Since there’s no in-game indication of which puzzles have been cleared in this manner, this is a bit of a pain.

All-in-all, the game is an excellent salute to the past, and a great example of the potential of fan-projects in general.