Chunsoft is one of the great pioneers of Japanese storytelling. In 1991, they developed and published Otogirisou (“St. John’s Wort”), a horror tale for the Super Famicom, involving a couple that get in a car accident and spend the night at a spooky mansion. This was followed up by the even more successful Kamaitachi no Yoru (“The Night of the Sickle Weasels”), taking place in a resort mansion haunted by demons. These were a unique type of a visual novels the company called “sound novels”, which feature text over minimalist graphics, accompanied by sound effects and music. They are structured like a choose-your-own-adventure story, where you read plenty of text and then make decisions at key points, sending you through a variety of good and bad endings.

This basic style was then used for the 1998 Saturn/PS1 game Machi: Unmei no Kousaten (“City: The Intersection of Fate”), though now featuring stills of digitized actors. This game was then followed up in 2009 by 428: Fuusasareta Shibuya de (“In a Blockaded Shibuya”), initially released for the Wii and then ported elsewhere. These later two titles were beloved by Japanese fans, with Machi being voted the 5th best game of all time in a 2006 reader voting poll by Famitsu Magazine, and 428 earning the coveted perfect 40/40 score from the same publication.

Despite how well loved these games were in Japan, they were scarcely known outside the country, as visual novels (and Japanese adventure games in general) are a tough sell to American and European audiences, especially when they were initially released. This is especially true in these cases due to their stark visuals and emphasis on storytelling over gameplay. Kamaitachi no Yoru was translated into English by Aksys in 2014 and released on iOS as Banshee’s Last Cry (given an extreme localization to change the setting from Japan to the United States in order to appeal to the more casual iPhone-using audience). This was the only Chunsoft sound novel available to non-Japanese speakers, until they decided to take a chance and localize a port of 428 for the PlayStation 4 and Windows. It’s now given the subtitle Shibuya Scramble, a reference to the setting of Shibuya, Tokyo, the intense criss-cross nature of the storytelling, and the world famous Scramble Crossing located within the city. The numeric title reference to both the single day where the story takes place (April 28, or 4/28), plus the Japanese characters for the numbers can be read as “shi-bu-ya” – a type of Japanese wordplay called goroawase – again referring to the locale. 428 is not technically a sequel to Machi, but since it uses similar mechanics and also takes place in Shibuya, so it’s viewed as its successor. It does have some references to it, though, at it takes place in the same universe ten years later.

Like Machi, 428 is presented entirely with still digitized pictures of actors, authentically shot on the streets of Shibuya. It’s a huge difference from typical visual novels, which just shuffle static portraits in front of various backgrounds. In order to effectively capture the drama, the actors still had to read dialogue (even though none of this is ever heard), and then the developers chose from well over 100,000 pictures to best represented each shot. There is some FMV, but it’s used very sparsely. This is probably for the best – the cheesy, amateur efforts from the 90s CD-ROM era still linger long after their heyday, and bad acting could potentially undercut whatever effects the writers were going for.

If you’d peg the story of 428 in any genre, it’d fit nicely as a thriller, focusing on a kidnapping of a teenage girl named Maria Osawa, who just so happens to be the daughter of a scientist of a gigantic pharmaceutical corporation. This in turn ties in with a terrorist plot involving the newly discovered Ua virus, which, if left unchecked, could have devastating effects on Tokyo, if not the entire world. In spite of the apocalyptic premise, it’s actually quite breezy and light-hearted in spots. As the story begins, Maria’s twin sister Hitomi is charged with making a handoff of a suitcase containing a ransom…and then things go hugely awry from there. There are five main viewpoint characters that you can switch between, each of whom serves a different role in the story.

Characters:

Achi Endo

The young adult son of the owner of Endo Electronics, Achi is so attached to Shibuya that he formed a gang, the SOS, to help protect it. He’s since left the organization, which has devolved into a group of thugs, but continues to help the city by picking up trash. He becomes embroiled in the central story pretty much by chance, running around with Hitomi Osawa, protecting her from a foreign mafia as well as a crazed assassin, as they investigate her sister’s kidnapping.

Shinya Kano

A detective assigned to the kidnapping case, on stakeout in Shibuya. Simultaneously, he’s dealing with a potential meeting with his fiancee’s gruff father. He swears by a code written down in his “Dick Diary”, inspired by a senior detective named Tateno. His partner is a strange man named Sasayama, who changes into increasingly absurd undercover costumes during the story.

Kenji Osawa

The father of the twins Maria and Hitomi, and a high ranking scientist in Okoshi Pharmaceuticals. His attachment to his work and detachment to everything and everyone around him sends him into a guilt spiral, as he learns his research into the Ua virus has put his family in danger.

Minoru Minorikawa

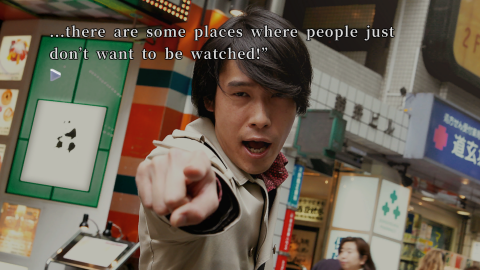

An abrasive (but talented) freelance writer who volunteers to help an old friend by saving his publishing company. He does this by running around Shibuya to interview as many people as possible to help fill the pages of a magazine before its deadline. This, of course, eventually leads him to cross with the main story. He loves to yell and point dramatically.

Tama

A mysterious girl stuck in a mascot cat suit, she ends up taking a temp job at a presentation to sell a shifty diet drink called Burning Hammer. Hers is the only of the main chapters told in the first person.

The story takes place across ten hours in a single day of Shibuya, with most chapters broken down by the hour, and even event further split down into increments as small as five minutes. In that way, it’s sort of like the early 2000s American TV show 24. When reading each story, you’re occasionally presented with multiple choice actions. All five characters’ stories run in parallel to each other, and actions in one can affect the other. And here is the game’s main gimmick – in any given character’s story, they’re predestined towards a “Bad End”, which can range from failing their objectives, or, more often, flat out getting killed. In order to stop this, you need to switch to another character and have them make a specific decision so the other can continue unabated. You can hop straight into any event you’ve already seen, so there’s very little time spent re-reading things you’re already familiar with.

The bad endings shouldn’t be regarded as failures on the part of the player – there’s simply no way to avoid many of these without clairvoyant powers (or using a FAQ). Instead, they show how drastically someone’s life can be affected by others, even things that seem inconsequential. Since time is of the essence for many characters, something that causes them to be even temporarily delayed can have catastrophic consequences. Indeed, the constant failures you’re forced to witness really just makes you root for the heroes even more. So you can view yourself, the player, as sort of a god, trying to find order in the chaos that is everyday life in order to save not only their lives, but everyone in Shibuya as well. The storylines finalize at the end of every hour, so once you’ve cleared it, you don’t have to worry about any previous choices affecting later outcomes. For example, a decision at 10:15 will not have affect beyond 11:00. This also prevents the story from having too many far reaching ripple effects, thankfully.

A key difference from Machi is while that story had multiple protagonists (eight in the original release, many more hidden or added in later ports), their stories didn’t directly intertwine despite their decisions affecting the others, plus many were written by different authors, making for wildly different tales. 428 is much more tightly wound together, with a central plot and the protagonists’ paths converging at several points.

At most bad ends, there’s a hint that tells you which character can prevent the outcome and when, so there’s rarely much guesswork in figuring out to do. The exception is in the last chapter (encompassing two hours), which not only removes the hints but makes the triggers much more complicated. At this point, you really just do need to experiment with different things, plus the true end in hidden behind a few flags that you may need to read about in a FAQ before you can unlock it.

A few times during each story, you’ll come across a “Keep Out”, booting you out of that particular thread. Theses usually involve the characters crossing in some way, so you need to play another’s story until you find their names highlighted, allowing you “Jump” back to it, open up the “Keep Out” and continue with the story. It seems contrived at first, but it does allow the story to keep some dramatic tension, since what happens in one story could spoil the others (and still does, on a few occasions).

The text also routinely highlights specific words or phrases, allowing you to access “Tips”. This concept should be familiar to anyone who’s played the Science Adventure games like Steins;Gate – most of the time, they give some background information on the term in question, but every once in awhile, it’ll be a humorous aside or a silly joke. There’s a sly, understated feel to much of the writing, the kind that’s rare in these types of games, and creates a very specific type of charm. The game was translated into English by Alexander O. Smith’s Kajiya Productions, known for their high quality of work with games like Final Fantasy XII and Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney, and 428 continues their consistent streak of excellent writing.

The storytelling also remains lively because it manages to balance the tones between serious drama and more overt silliness. Obviously the characters closer the main story – Achi and Hitomi’s escape, Kano’s police work – lean more towards action. Osawa’s introspections are more emotional, though they keep from getting too overwrought since the otherwise stunted protagonist has a curious affliction for a J-pop star and enjoys posting on message board forums, while the oddball detective Kajiwara (sort of like a Japanese Colombo) consistently lightens the mood. Meanwhile, Minorikawa’s story is a bit sillier, just because he’s such a over-the-top character, dealing with some of Shibuya’s stranger denizens, typically by berating them into giving interviews. Even his story has an aura of despair over it, because it’s made clear that if they can’t finish the magazine in time, his friend will commit suicide and leave his daughter without a father.

Tama’s initially seems more divorced from the main story, and by far the silliest, especially when dealing with their boss, the perpetually unlucky business man Yanagishita, whose actor pulls off a stunning amount of physical comedy despite (mostly) being limited to still pictures. There are a few parts where the story gets a little too goofy or incredulous – the super powerful adolescent assassin girl Canaan strains credibility, even in a scenario involving deadly viruses, CIA agents, and international terrorists. Plus it features cameos by real life pop star Aya Kamiki, whose song “Sekai wa Sore Demo Kawari wa Shinai” routinely appears in the game. Though to players who aren’t familiar with Japanese pop, she may as well be a fictional character anyway, so her presence won’t feel quite as cheesy.

It’s also extraordinarily well paced. Many visual novels tend to be overwritten, but since the story here keeps to a strict, roughly real time schedule, there’s rarely any time for it to dawdle meaninglessly, and in the cases where nothing of consequence is happening, the game simply skips over those time blocks. The plot remains riveting from pretty much the get-go, and escalates naturally over the course of the day, culminating in a brilliant finale where all of the disparate threads (including some unexpected ones) finally comes together. Indeed, while many visual novels are inspired by manga or anime, 428 feels more like a television drama, not only with its visuals but also the type of story it’s telling. Its wide variety of characters allow for a variety of perspectives and conflicts, like Kano’s hero worship, and Osawa’s parental guilt, while Achi’s attitude still makes room for a typical selfless do-gooder. In other words, the game largely steers clear of many visual novels tropes some might find offputting.

There’s quite a bit of bonus content after the main story. In addition to a weird Wizardry-style wireframe dungeon (which acts more like a puzzle rather than an actual first person dungeon crawler), there’s a meta-game to find as many bad endings as possible (there are over 80 of them), plus there’s a pop quiz about various in-game facts. These can unlock brief stories focusing on the many secondary characters. There are two larger scenarios too – one written by Kamaitachi no Yoru scribe Takemaru Abiko, which acts as an epilogue for the main story, and the other by Type-Moon, the studio behind games/anime such as Fate/Stay Night, focusing on Maria’s assassin friend Canaan. This is by the far the most divergent story of the game, since it’s presented with drawn anime stills instead of live action photography, plus there’s voice acted dialogue. This was actually a prologue to a spinoff anime, also called Canaan, which actually managed to be localized into English back in 2010, long before 428 officially left in Japan. (This anime contains some spoilers for the game, so don’t watch it first!) This chapter is so strange because it’s so drastically different, though it does sort of explain why Canaan seems less grounded and more “anime” even within the main game. There are a few other things to unlock too, including a recreation of Koichi Nakamura’s (Chunsoft’s founder) classic game Door Door, starring Eco, the environmentally themed mascot on Achi’s shirt.

428 was written by Yukinori Kitajima, who worked on assorted novels, and whose first game was RPG 3 Ben B Gumi Kinpachi Sensei: Densetsu no Kyoudan ni Tate!, also by Chunsoft. Since then, he’s also contributed to 9 Persons, 9 Hours, 9 Doors, Ace Attorney vs. Professor Layton, Ace Attorney 5, and several Senran Kagura games. He also wrote Level 5’s 3DS/PSP/Vita game Time Travelers, which takes place in the same universe as 428, though 20 years later.

Altogether, 428 works so well because there are so many different characters, so many tones, so many themes, that somehow interweave together into an extremely satisfying whole. It’s riveting, it’s silly, it’s emotional, it’s weird, but it’s all extraordinarily effective and ultimately unforgettable, making it essential reading for anyone interesting in video game storytelling.