When Ensemble Studios made the original Age of Empires in 1997, few seemed to expect that this Civilization-inspired work would spawn what has since been considered one of the classic franchises in the real time strategy genre. Although not the first of its kind, the series stood out sharply from the fantasy and science fiction themes of many other RTS – barring the fantastical, if still somewhat historical spin-off Age of Mythology – in the process codifying many staple mechanics that fans of the genre tend to take for granted. All the while helping popularize historical gaming and set a precedent for games as varied as Rise of Nations, the Cossacks series and the Total War saga.

Thus, when Age of Empires III came out in 2005, there was much in the way of anticipation. Moving the setting forward in time into the Age of Exploration and introducing new twists into the established formula, the game went on to win GameSpy’s “Top Ten PC Games of the Year” and PC Gamer’s “Editors’ Choice” for the same year; around two million copies were sold by 2008. But though the game had received generally good reviews upon release, AoE III had gained something of a mixed response from gamers and fans. Whether it’s the introduction of the RPG-like “Home City” system, a single-player campaign that largely deviated from previous entries or the tweaks done to gameplay, some saw it as lacking and paling in comparison to its predecessors. Others even went so far as to view it as a disappointment if not a “huge mistake,” as series co-creator Bruce Shelley was quoted as saying in a sensational Kotaku article in 2011; with regards to the game, the article also highlighted how the developers may have made too many deviations from the mold such that Shelley even tried to have Microsoft rebrand it away from being a direct sequel, further adding fuel to the fire. By that point, though, the series itself seemed to risk sliding into limbo thanks to Ensemble Studios having since closed down and a changing environment where the likes of Starcraft II and MOBAs were beginning to gain popularity versus more conventional RTS titles.

It’s no surprise, then why Age of Empires III tends to be seen at least by some as a black sheep in the series. But long after the dust has settled, perhaps it’s time for another look. In light of rekindled popularity through its Complete Edition on Steam, a persistent modding community and renewed interest in the franchise itself, it makes one wonder whether the game really does stand the test of time.

A New World

What stands out immediately from the get-go is the setting. Age of Empires III takes off more or less from where Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings ended, spanning the Age of Exploration up to the mid-19th Century. Befitting the premise, it’s not surprising that the New World features heavily, maps largely being based on various locations in North and South America with a considerable emphasis on exploration. In addition, the game makes an effort to reflect the social and technological changes that happened in that timeframe through the five Ages (Discovery, Colonial, Fortress, Industrial, Imperial) depicted as lands are discovered, settled and fought over. This also means that firearms and other gunpowder-based weapons take decidedly more prominence in gameplay, especially in later Ages; it’s no surprise that, while pikes, swords, bows and halberds are still very much present, ranks of musketeers and cannons are spotlighted in the game’s art. And while the game doesn’t put much focus on issues like slavery, neither does it really trivialize topics related to the period like colonialism, which are instead treated as historical givens. In classic AoE fashion, it’s left to the player rather than spoon-fed.

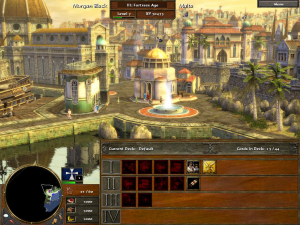

The graphics and overall audio make a solid effort to drive the new changes home. Although AoE III’s not the first 3D entry in the series – that honor belonging to Age of Mythology – it nonetheless doesn’t shy from embracing graphical fidelity to new levels, mirroring the trend of other RTS games of the period. To that end, the developers made a point to give as much attention to detail and scale as possible, be it the finely-textured structures, radiant vistas or even the large galleons traversing the vibrant seas. The incorporation of the Havoc physics engine meanwhile allows for more dynamic, destructive spectacles such as cannonballs ripping through units or buildings buckle under the weight of enemy attacks rather than simply burning to show damage, and all with proper physics and ragdoll effects. Coupled with a vibrant color pallet and copious bloom effects, the game comes across as stylized and more than a little dream-like without sacrificing too much grounded realism. This is to say nothing of the generally solid sound design and ambiance which all match fittingly with the setting, complete with a soundtrack that combines original orchestral setpieces, folk-inspired rustic tunes and Native American influences. Or how, as an added touch, a variety of languages are used for the voice acting, even if it’s for mercenary and one-off units; these can range from the usual suspects like French and Spanish to Scottish, Swiss German, a plethora of rather accurate Native American tongues (such as Cherokee) and even Japanese. Granted, the presentation can be dissonant at points, especially as cannon fire rips through masses of infantry. Even now, it speaks volumes of how much the presentation holds up and how much effort was put in by the developers.

AoE III’s gameplay itself, while building on the same basic mechanics established in earlier games, tries to incorporate and streamline elements taken from those very predecessors – especially Age of Mythology – in various ways to improve on the formula. Settlers, for instance no longer require warehouses or camps to bring in their gathered resources – in effect allowing them to be virtually autonomous much like Atlantean citizens in AoM – while most military units can be trained in groups of up to five, making it possible to field sizable armies more quickly albeit at a heftier price. Explorers are hero units that double as scouts, grow more powerful with each Age and can be recovered (for a certain amount) instead of being permanently killed. Maps are filled with random bonus-giving treasures (which take the place of relics in older titles) that can be claimed by wiping out any surrounding “guardians,” whether it’s a pair of bears or a band of rogue cowboys. “Aging up” involves choosing a “politician” that provides additional units or bonuses, similar to choosing minor gods for the same purpose in AoM. The static settlement system also from that spin-off, meanwhile, has been modified in the form of trading posts, which are not only built along pre-existing trade routes for a steady stream of various resources (and could be upgraded into stagecoach and railroad lines given enough time) but also play into the “Native Allies” mechanic. Setting up such posts in certain villages scattered throughout the map (each one representing various Native American cultures like the Cree and Inca) not only grants access to special upgrades and techniques, but also unique indigenous units to complement armies. All the while incorporating classic game modes and updating the established “rock-paper-scissors” unit dynamic to accommodate archaic, modernized and mixed builds alike. The end result generally makes for fluid, dynamic matches that while noticeably distinct from other games in the series doesn’t sacrifice the established formula.

The playable nations, meanwhile, while more limited compared to Age of Kings, similarly make an effort to be as distinct as possible. With the exception of the Ottoman Empire, the eight-man roster is comprised entirely of European factions (that at the very least had some historical capability of settling in the New World) such that British and Spanish. Each one of them has unique units, perks and in some cases, buildings that all play into their respective strengths. The Dutch, for instance can build gold-generating banks to bolster their financial bonuses, while the Russians can fill their ranks with expendable masses of infantry. Given the timeframe, they also inevitably come across as relatively anachronistic even with Age-related upgrades put into account, some being more blatant than others; it can be a tad weird to find British longbowmen fighting alongside 18th Century Redcoats or comparing the somewhat archaic Spanish unit roster with the more Napoleonic one for the French. Which isn’t even getting to how each one, building on trends in mimicking multiplayer experiences and live players seen in Age of Kings and Age of Mythology, has an AI personality (representing leaders like Suleiman the Magnificent and Queen Elizabeth I) that not only has voiced taunts reflecting its respective culture, but can respond dynamically to your actions to a point and even remember whether it’s won or lost matches. Granted, the aesthetic differences between each nation aren’t as pronounced as they’d otherwise be – the Ottomans, even with their Janissaries and Islamic touches, still share the same general palette as the Portuguese – and leave a bit to be desired. But even with that caveat, the way AoE III tries to make factions even more varied than before is commendable though not always as intended.

Compared to previous entries, the multiplayer has seen a considerable overhaul. While online and LAN connectivity weren’t strangers to the franchise by that point – AoM in particular was the first to use Ensemble Studios Online (ESO) – AoE III has its multiplayer integrated into the game’s interface to a much greater extent. Players can easily find others through ESO matchmaking, and also have access to a host of other features such as the ability to set up clans and a ranking system that helps balance out matches, mitigating any unfair “veteran rips newbie” scenarios. In addition to accessibility, this has helped extend the game’s longevity provide a rather seamless, largely trouble-free experience that brings the series firmly into the 21st Century. As of this posting, not only are the ESO servers for AoE III still live, but they also remain remarkably active for an old game with hundreds if not thousands of people playing on average.

The most significant inclusion though, for good or ill, would arguably be the “Home City.” An attempt to incorporate RPG-style elements into the series, the idea behind this much touted feature is to provide a persistent “character” that would “level up” in both single-player skirmish and multiplayer, with said “character” representing your faction’s homeland, the Home City often being based on a major port or the capital. This features as well in gameplay, as experience gained over the course of a match – this is usually earned by killing enemies, getting certain treasures or just gathering resources – not only helps “level up” said Home City but also (at certain thresholds) unlocks the ability to use cards from a shipment deck that can provide useful benefits, if not turn the tide of battle if played just right. The further up you go, the more varied and powerful the cards become, ranging from extra supplies, reinforcements and mercenaries to nation-specific upgrades, team-wide bonuses and potent unit enhancements and shipment-only specials like factories and elite regiments. On paper and in practice, this allows for significant customization as well as a degree of unpredictability if not challenge. This is especially evident in multiplayer, where Home Cities both complement the ranking system and provide an added sense of character. In other respects, however, its execution is less than successful. It can take quite a bit of time to “level up” especially in single-player, which can lead to some grinding just to rank up the later levels. Neither is the payoff as rewarding given how, improved decks, better cards and high-tier unlockables notwithstanding, “character” upgrades (such as speech bubbles and new building colors) are mostly cosmetic. Which isn’t getting to how accessing the Home City in the middle of gameplay tends to break the pacing, at times seeming as though existing in a vacuum even in the midst of a massive battle. One gets the impression that while undoubtedly an innovation that’s helped AoE III stand out from other RTS games at the time, it’s held back from of its potential and to this day hasn’t really been replicated. What is present, though, is still impressive for what it’s worth.

The same couldn’t really be said of the single-player campaign, which breaks from the mold with rather mixed results. The three-act tale chronicles three generations of the Black Family, from the Siege of Malta in the 16th Century to the frontier of early 19th Century America. Unlike the other main games, however, history takes more of a backseat, at points seeming more like an afterthought; the story focuses instead on the Blacks’ centuries-long struggle against the mysterious Circle of Ossus involving the legendary Fountain of Youth. While events like the Seven Years War do intersect at times – complete with a cameo by a younger George Washington as a colonel in the British Army – you’re treated to something more befitting Assassins’ Creed (with the Circle’s schemes and antics against the Blacks foreshadowing the Templars) than Age of Empires; even the fantastical, cross-mythological narrative of Age of Mythology made more effort to put attention to the source material. That isn’t to say that the campaign doesn’t have its moments, particularly in its solid presentation, varied objectives, decent if at times cheesy acting and how each successive member of the Black Family grows more and more “native” to the New World; compare the very Scottish knight, Morgan Black to his mixed-race, American descendant Amelia Black. Or how the Home City system is integrated into the campaign mode, where accomplishing objectives can provide substantial experience boosts and thus access to better shipment cards. But for a series that has for the most part featured some degree of educational value upfront in its historical fiction, it sticks out like a weird deviation if not a sore thumb from other entries and even in contrast to the rest of the game.

Which isn’t getting to other unavoidable issues. The graphics, beautiful as they are, can still tax older PCs due to AoE III’s system requirements; while not quite as resource-hogging as relative contemporary Company of Heroes (released in 2006), for a RTS of the time it’s somewhat demanding if one want performance beyond the bare minimum. Pathfinding bugs combined with unit scale mean that it’s not unheard of for those grandiose frigates to glitch about in otherwise traversable canals or whole regiments getting stuck while going from A to B. While multiplayer is sound, the ranking system (based on both Home City level and ESO rank) and the fact that a Home City used for offline skirmish can’t be carried over may not be for everyone. The AI, meanwhile, for all the effort put in difficulty and mimicking real opponents can become predictable if not repetitive after a while, which could make “grinding up” a Home City more tedious and may limit the game’s longevity offline. The changes and streamlining done to the gameplay itself, though generally successful, may come across by those more familiar with past entries as too simplified and different.

Even with the setbacks and faults – and perhaps in spite of the worries from some of the developers – AoE III remains an impressive game in its own right. Though the game may not surpass the lofty standards set up by its predecessors, it still doesn’t stop it from being on par at least. Indeed, it would become popular enough for an expansion pack to be green lit not long after release. One that would provide an ample opportunity for the developers to further work on and improve the foundations that had been set up.

The Warchiefs (2006)

Ensemble Studios released The Warchiefs in 2006, with quite a bit of anticipation. The title of Age of Empires III’s first expansion alone gives away one of its main selling points: making the Native Americans fully fleshed out in their own right. And not only that, but also all the while building on what’s worked and bringing back more classic elements.

From among the otherwise minor Native Allies, three new civilizations are brought into the fray: the Iroquois, Sioux and Aztecs; the latter in particular had made an earlier appearance in Age of Kings’ expansion, The Conquerors in 1999. Compared to the main game’s factions, however, each one is deliberately made to look and feel more distinct from each other – each of them even speaking accurate forms of their respective languages like Nahuatl – such that from a glance, one can’t mistake any of them for being identical. This extends to their strengths and bonuses, be it the Sioux’s strong emphasis on mobility by horseback (most exemplified by their famed Dog Soldiers) or the somewhat “Europeanized” unit roster of the Iroquois (being the only ones with access to cannons). The traits they do have in common are intended to further distinguish them from the Europeans, such as having “Fire Pits” (where villagers can dance for various bonuses) and warriors capable of stealth, which compensate for their generally inferior technology; this is especially evident for the Aztecs, who lack any gunpowder and cavalry units of any sort. Then there are Warchiefs themselves. Taking the place of Explorers for the Native Americans, they’re able to convert treasure guardians, provide passive bonuses to friendly units and become much more powerful with each successive Age. While they’re not guaranteed to defeat regiments of enemy musketeers single-handedly, they can quickly turn the tide of battle when played right. As an added touch, their Home Cities are represented by tribal councils – save for the Aztecs and their nicely rendered capital of Tenochtitlan – and their respective leaders are given fitting AI personalities (such as the proud if hammy Montezuma) without being too dependent on clichés.

The two “acts” comprising the single-player campaign also feature these cultures. Serving as both a sidestory and epilogue to the Black Family saga (the latter stretching the game’s timeframe into the 1870s), there’s a noticeable shift back to more traditional Age of Empires conventions, though the Aztecs are oddly absent. Instead of rehashing or continuing the Circle of Ossus and Fountain of Youth plotlines, much more attention has been placed on the historical aspects that had been previously been sidelined – be it the Iroquois involvement in the American Revolution or the events leading up to and during “Custer’s Last Stand” at Little Bighorn – with the Blacks being caught up in the middle. While the stories told can be a bit predictable (such as Amelia’s half-Sioux son Chayton finding himself torn between two worlds), they manage to provide a more personal take on the characters as well as a decent justification/tutorial for the Native American mechanics, further helped along by solid pacing and new tracks that easily fit the expansion’s motif. And in classic series fashion, it succeeds better in delivering rather bittersweet take on history that respects each side of the conflicts depicted without resorting to cheap “evil white man” and “noble savage” clichés that would otherwise be all too tempting for something like The Warchiefs.

This isn’t to say that the original civilizations are left out. Along with a new “Native Embassy” building that allows you to recruit indigenous units (so long as you remain allied with the corresponding tribes), the expansion introduces the “Saloon,” which makes it possible to recruit outlaws and mercenaries outside of a Home City for a sum of gold (be it lowlife bandits or expensive, powerful soldiers of fortune like Italian Elmeti) as well as units like horse artillery, petards (“suicide bomb” units that function just like their counterparts in Age of Kings) and spies that can also counter any interloping Explorer or Warchief. But the most significant addition for the “vanilla” nations, arguably, would be the “Revolution” mechanic: instead of simply going into the Imperial Age, your colony now has the option of rebelling against the homeland under leaders such as Washington and Bolivar, in the process gaining access to powerful end-game units like Gatling Guns; the soundtrack even changes to be much more reminiscent of American folk music to reflect this shift. This is counteracted, however, by how rebelling cripples your faction’s economy (by turning every single settler into militia), making it a risky gamble that could easily backfire unless you’re willing or desperate enough.

Yet for all the new additions and adjustments – which also include new maps, Native Allies like the Navajo and Huron, and a “Trade Monopoly” victory condition based on trading post control – not everything has worked out for the better. The Native American factions, whether as a consequence of balancing, tend to function closely enough like their European counterparts that they can come across for some as more of the same in different skins. Indeed, even with the attempts to bring back elements from past entries, the gameplay still doesn’t quite succeed in downplaying the changes that have occurred between AoE III and Age of Kings. Which isn’t getting to how the Home City system, though tweaked and with a higher level cap among others, remains more or less unchanged, with the Native American ones not even having unlockable cosmetic upgrades.

Such faults, however, don’t significantly tarnish how The Warchiefs largely succeeds at once in returning to old form and polishing the changes brought about in AoE III, especially with the patches. In spite of whatever concerns may have emerged by then, the game in its “Gold Edition” (which includes the expansion) continued to garner enough sales and popularity for one more significant addition, albeit one that would take it to unexpected territory.

The Asian Dynasties (2007)

The second and last official expansion pack, The Asian Dynasties was released in 2007 and is notable for more than its premise. The titular Asian spotlight notwithstanding, for the first time in the series, Ensemble Studios wasn’t alone in its development. Instead, it’s the child of Big Huge Games of Rise of Nations fame. And this fact shows in how it differentiates itself, even while being remarkably faithful to the rest of the overall franchise.

Befitting the title, three varied new civilizations are introduced into the game: the Chinese, Japanese and Indians. Compared even to the Native American factions in The Warchiefs, there’s a considerable effort made to distinguish them from both each other and from the rest of the roster, whether it’s the Japanese’s ability to attract wildlife to their shrines instead of hunting them or how Chinese units are trained in myriad “Banner Army” configurations that can respond to various threats. There’s also the overall way Asian nations Age up by building “Wonders” that grant various bonuses and abilities, similar to their equivalents in Rise of Nations; the Indians’ Red Fort doubles as a defensive castle, for instance, that can be upgraded to be even more powerful. This extends as well to an altered tech tree, monasteries taking the place of saloons and how their Monks (the Asian take on Explorer and Warchief units) look and function rather differently, complete with ones riding atop elephants. As an added touch, not only are their respective leaders/AI personalities given due dignity, but the various unique units tend to speak in different tongues don’t normally pop up, such as Manchu or the Hiroshima dialect of Japanese. Granted, there’s still a bit in the way of anachronisms; the Chinese are a mélange of Ming and Qing Dynasty influences, Japan looks seemingly straight out of the Sengoku period, while in contrast the Indians are largely based on the 19th Century with some Mughal-style touches. But compared to the other nations, the results speak for themselves.

In addition to new maps based on various parts of Asia – complete with new types of Native Allies like Jesuit Missions and the Shaolin monks – and the introduction of naval treasures among others, a major addition to gameplay is the passively gathered “export” resource accessible to Asian nations, which in turn is related to the “Consulate” system. Building consulates allows you to establish ties with certain European powers (or go isolationist, if playing as Japan) for various bonuses, depending on the faction. Such ties also provide more tangible benefits – be it shipped fortifications from the Russians, a British expeditionary force full of Redcoats and artillery or even unique Japanese units like shinobi for isolationists – provided enough export. You can, however, decide how much export is generated at any given time through those same consulates, albeit at the expense of your actual economy the more you opt to be dependent on those ties. These in turn open new strategies and risks that could either backfire horribly or turn the tide of battle, all while giving a sly nod to how such arrangements actually played out in real history; all that added firepower and support come with strings attached which, if you’re not careful could wind up self-defeating in the long run.

The three distinct campaigns, meanwhile, are also much more akin to Age of Kings than the rest of AoE III, dropping the Black Family saga altogether in favor of self-contained stories involving each of the Asian nations. Save for the Chinese campaign – which follows a “what if” scenario based on claims that Zheng He’s fleet may have reached America before Columbus – they are heavily focused around real historical events, such as the Sepoy Rebellion for India and the Battle of Sekigahara for the Japanese. It becomes evident that much attention was put in the various arcs in terms of authenticity; in the case of the Chinese arc, the developers still made a point to keep it somewhat grounded despite the fantastical premise, while the Indian one is all but lifted from the life of revolutionary figure Nana Sahib. This also extends to how the campaigns retain the solid pacing and production values of an Ensemble Studios production, while providing ample opportunity to let you grow familiar with the new factions. If anything, they show not only how much Big Huge Games respects the material but also how the franchise could potentially survive even without Ensemble Studios’ guidance, provided the right hands.

Needless to say, The Asian Dynasties is not without some blemishes. Most of the new additions are rather lopsided in favor of the new nations, which can make the rest of the lineup seem left out altogether. In addition to Asian factions coming across so distinct that they unwittingly make the similarities among the Europeans and Native Americans all the more glaring, the focus away from the New World can seem a bit jarring. Even with the improvements across the board and the patches, the pathfinding and graphical issues from the game was first released in 2005 never really went away. And like The Warchiefs, there’s limited customization for Asian Home Cities, with cosmetic options being nigh nonexistent. One gets the impression that more could have been done, which isn’t to discount what’s already there.

Even with the inconsistencies and flaws though, the expansion more than succeeds in providing a fresh take on the game that stays faithful to the Age of Empires name. If anything, it’s contributed a good deal to the series’ popularity and visibility among RTS fans well after release.

By the time the Complete Collection (containing all the expansion packs and patches) came out on Steam in 2009, however, AoE III risked being the last main entry in the franchise. In January of that year and following the development of its last game Halo Wars, Ensemble Studios closed down permanently. With the growing popularity of MOBAs and with RTS behemoths like Starcraft 2 all but stealing the spotlight, the likes of the Age of Empires series were increasingly seen (at least by some) as an outdated dinosaur left behind into the dustbin of gaming history. Microsoft for its part attempted to keep the series going with Age of Empires Online in 2011, only to close down the servers three years later due to being “too expensive” to maintain.

It seemed like the storied franchise that helped popularize and codify the RTS genre wasn’t just in limbo, but was on the brink of oblivion. Not everyone, though, agreed with the sentiment. Much like with the Command and Conquer saga, fans of the Age of Empires series saw it fit to keep the embers alive. Their efforts, however, didn’t stop with forming a niche that grew as more strategy gamers returned to the genre’s roots or even attempting (successfully) to revive Age of Empires Online through “Project Celeste’s” fan server. Some among them have cultivated a small but persistent modding community spanning across entries in the franchise, AoE III included.

Mod Spotlight: Wars of Liberty

Paralleling the continuing mod support given to Age of Kings – which contributed to the release of a HD re-release on Steam in 2012 and The Forgotten the following year by modders-turned-development house Forgotten Empires (who as of this post even have ex-Ensemble Studios senior engineers among its ranks) and SkyBox Labs – Age of Empires III has more than its share of mods, some which continue to see active development, with even a few new ones popping up as of this posting. Enough time has passed that the ensuing works, at their best, would impress Ensemble Studios if it were still around. One such passion project is Wars of Liberty.

The backstory of Wars of Liberty, which has been in development since 2006 and continues to receive update patches, is as noteworthy as the mod itself. Beginning as War of the Triple Alliance, it originally focused around Latin America and in particular the titular conflict – fought in the 19th Century between Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay on one side and Paraguay on the other – which while lesser known outside South America is often considered one of the bloodiest wars waged there. Despite periods of seeming inactivity and myriad difficulties, it eventually attracted interest from Latin American and eventually, Anglophone gaming circles. Its scope expanded to include factions as far afield as North America, the Balkans, Middle East and Africa; it helped that some of these additions were incorporated from other abandoned projects that the modders were involved in. Eventually, the mod had evolved to the point wherein the planned “Delta” release in 2015 was retooled into what it is now, complete with its present name. The result after all those years in development (its current form requiring all the expansions and patches) is a work that’s at as much an evolution of AoE III as it is a fan sequel in all but name.

One of the mod’s major features is a substantially expanded list of playable nations (with over 40 available), including those that don’t usually get featured in RTS games, if at all. It’s not often that you get to play tribal peoples like the Tupi, lesser-known European powers like Habsburg Austria or the oft-neglected Brazilians. But instead of being simple reskins and palette swaps of existing sides however, the modders seem to have taken some cues from The Asian Dynasties and Rise of Nations. Much has been done on making each one (and each general “cultural group”) as distinct as possible. Latin American factions like the Mexicans and Argentinians, are as distinct (in terms of architecture, strengths, overall aesthetics. units and so on) from African ones like the Ethiopians as they are from each other. This also extends to more varied tech trees, pronounced national traits/bonuses, separate hero units and unique gameplay mechanics; Serbians, for instance, are able to torch their own structures “scorched earth”-style, while the Americans can choose between “Union” and “Confederate” routes as they Age up. The modders have even gone to the extent of sorting out balancing and difficulty levels for each cultural group and nation. The scope as a consequence is decidedly much more global, which surprisingly complements AoE III’s original New World focus and doesn’t make you feel overwhelmed.

Another aspect, which has remained consistent throughout Wars of Liberty’s various incarnations, is how AoE III’s timeframe is more focused towards the 19th Century onwards. This seemingly small detail influences most of the mod’s changes, in more ways than just new sounds or scenery. Many factions, for one, were overhauled – from aesthetics and models to Home Cities and whole unit rosters – so as to be accurate to the broadly Napoleonic, Victorian and even early 20th Century periods covered while mitigating some of the more glaring anachronisms; this time around, the Japanese no longer look like they’re from the Sengoku era, while the Spanish lineup is much more modernized than their original one. At least some of the new cultural group mechanics are similarly designed to reflect the times depicted, such the Latin Americans being able to build post offices allowing them to attract unique “Immigrant” groups. And as it immediately becomes clear, the mod doesn’t shy away from topics like slavery, colonialism, revolution and imperialism, instead approaching them in a more upfront manner than the original game while – in keeping true with both the source material and series tradition – treating such topics as historical reality, warts and all. As potentially controversial as stuff like Confederate-route Americans and Brazilians being able to buy slaves with gold may be for some, the changes provide a more educational and insightful experience without sacrificing the overall tone (darker as it might be) or patronizing players.

This isn’t getting to how the mod goes through lengths to improve AoE III’s gameplay by taking inspiration from the rest of the franchise and other RTS classics like of Rise of Nations or Empire Earth. The Home City system is integrated even further into gameplay, especially in how shipments and experience points are incorporated into certain nation and cultural group-specific mechanics. Religion figures much more as well – alongside with the introduction of a new “faith” resource – making it possible to choose various creeds to follow depending on the faction (ranging from Catholicism to Shinto to atheism), each with their own bonuses and potentially powerful perks, complete with clerics capable of both healing friendlies and condemning foes to death. Some of the new maps introduced, meanwhile, have in addition to new Native Allies particular gimmicks that can make matches more interesting, such as the Congo map having almost little visibility in the jungle. There are even references made to past entries in the series, be it subtle (with some Greek units using soundbites from Age of Mythology) or explicit (the Maltese designed to be reminiscent of an Age of Kings faction in terms of units and playstyle). At times, it can almost seem like a thinly veiled love letter to the historical RTS games of yesteryear even while pushing the series into new ground.

Mind, it’s still a work in progress when all’s said and done. Naturally, there remain bugs, unfinished content and planned additions aplenty, including new factions like the Belgians, a campaign mode and even the incorporation of World War I as the sixth, final Age. But what’s present in Wars of Liberty is an impressive feat that stays true to the material that earns its high rankings on ModDB, though it’s not the only diamond in the rough; others of similar caliber include the Ottoman Empire Mod (which thoroughly overhauls the titular faction), Struggle of Indonesia (which increasingly focuses on Southeast Asia in general) and Napoleonic Era (which substantially expounds upon the European nations). That these fan projects tend to be affiliated with one another further help in both raising the standards expected among modders and sustaining a remarkably international community. All of which, in one way or another demonstrate how dynamic and solid the underlying game that’s AoE III really is, once again in spite of series co-creator Bruce Shelley’s fears.

This is saying nothing on how the game’s continued longevity, alongside its predecessors, has contributed to the franchise’s persistence among strategy gamers. Whether it’s the Age of Mythology remaster or entirely new content in the form of DLC expansions, the years following 2012 didn’t just signify rekindled interest on Microsoft’s part – in noticeable contrast to EA and Command and Conquer’s limbo status – but also an implicit, official acknowledgement that there remains a stable, lucrative niche for more traditional RTS, one that’s grown even more vibrant despite its size. Then in late 2017, it’s revealed that among the games announced alongside the reveal of Age of Empires IV (to be developed by Relic Entertainment of Company of Heroes fame) is Age of Empires III: Definitive Edition, potentially giving it the same treatment as with other entries. It seemed like for fans, all those years of dedication have finally been vindicated.

In light of all that, perhaps it’s premature if not unfair to call AoE III a “huge mistake,” just as it is to pull the curtain down on the Age of Empires series as a whole. Its efforts in combining convention and change, including the flawed yet innovative Home City, into an entertaining package help make it stand out now just as over a decade ago. And while the “good old days” when old-school RTS were significantly popular may not come back and the game itself may not surpass the high expectations set by its predecessors, it still more than carries its weight around; its planned remaster further means that its longevity for the foreseeable future is likely to be assured. Even now, you’d be hard pressed to find a game of its type that manages to capture the Age of Exploration and beyond in such a fun, insightful way.

So at least until the next chapter in the storied saga comes along, there’s more than ample room and time to sally forth into the frontier and leave a mark on history.