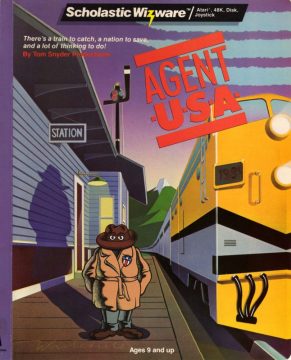

While console gaming was controlled by the companies that made the consoles themselves, computer gaming was always more unrestrained, allowing for more experimentation, more companies making games, and as a result, could even be called the first true indie scene. Some early computer games are even nearly impossible to classify under a known genre. One of these is Agent USA, a game published by Scholastic – that’s right, the occasionally educational book company best known for non-educational fare such as Goosebumps – and developed by Tom Snyder Productions – yes, the same Tom Snyder who created the cartoon Dr. Katz, Professional Therapist.

The game features a combination of mild action-like elements, mild strategic planning, and elements of real time simulation. It’s also the kind of thing that would be unlikely to be created by today’s indie scene, due to the sheer weirdness of its theme and ideas, and the limited nature of its gameplay.

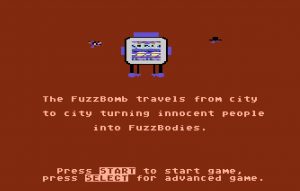

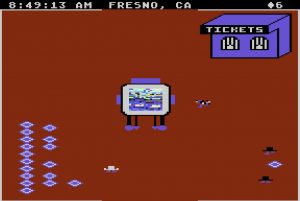

The story is that Elma Sniddle, a scientist trying to build a new kind of TV, accidentally created an abomination called the FuzzBomb, which began transforming people into “FuzzBodies:” people whose bodies are covered with TV static, who lose all their free will and begin to travel around the country touching other people to transform them into FuzzBodies as well. You are tasked with stopping this unusual form of pseudo-zombie apocalypse. Who are you? Agent USA, but what government agency you presumably work for is left unstated.

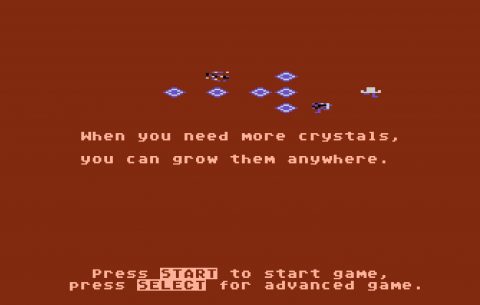

So what does Agent USA do? The gameplay is fairly simple at its core but also very original even by modern standards. It’s also somewhat complicated, so the game actually contains an element super rare for its era: a built-in explanation.

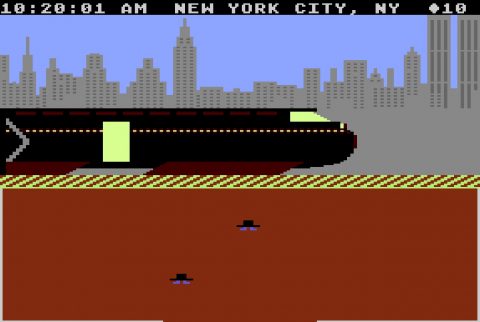

The 48 contiguous United States have all their major cities connected by trains. The 11 most important cities, such as New York City and Dallas, have high speed bullet trains that connect to each other. The state capitals all have information booths that contain various useful information. And the trains all run on time.

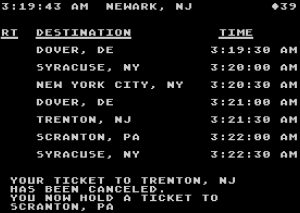

In each city, there is a schedule of all the trains, where they’ll go and when they’ll arrive down to the absolute second and which ones are bullet trains rather than steam locomotives. You have to type in the exact name of the city you want a ticket for, and then go and wait for that train to arrive. Or you can cheat, as any locomotive can be entered if you hop on a second before it leaves. Any time sooner than that, and you’ll get kicked off. That trick doesn’t work on bullet trains; those people won’t even let you on without a ticket!

Amusingly, there’s a minor glitch where if you enter a train exactly a second before it leaves without a ticket, the train will leave the screen but without it counting as you riding it or counting as you having left. The only thing you can do is push down to exit the missing train to get back on the ground.

Then there’s the crystals and FuzzBodies.

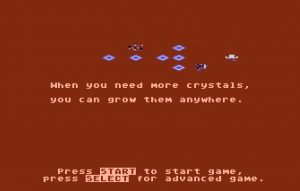

You can plant crystals in the ground by holding the controller button and walking. New crystals soon start to grow, but they also attract the attention of the game’s civilians, who all seem to have no understanding of the concept of personal property and soon make a beeline right for them. So you basically have to cultivate crystals from your impromptu makeshift farm, and keep them safe from the grabby hand idiots. Luckily these idiots can also be pushed around and walk in the direction they were pushed. You could try to push all of them out of the area, then head to a corner and start planting your crystals and be ready to guard them. Even push the civilians onto trains to force them to leave!

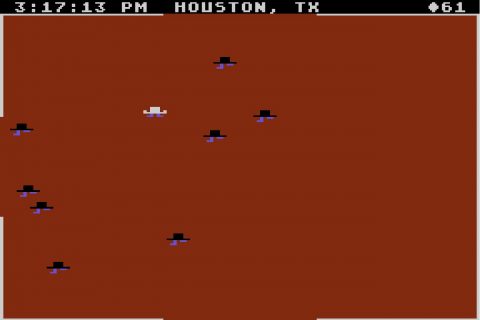

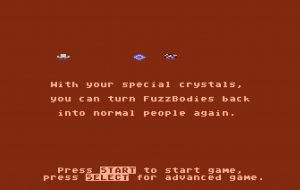

Crystals are the only line of defense against the FuzzBodies. When they show up, panicked civilians will start dropping crystals of their own until they run out. If a civilian with no crystals left is touched by a FuzzBody, they become a FuzzBody. If a FuzzBody touches a crystal, they become a regular civilian. But if you get touched by a FuzzBody, you lose half your crystals unless you have none left. Then, you also become a FuzzBody, and lose all control of your character!

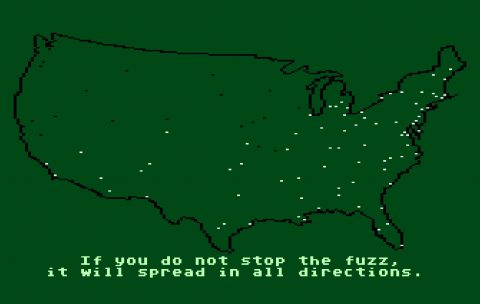

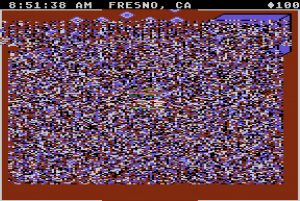

As a FuzzBody, you literally have no free will, and you simply move around randomly, even getting onto trains and spreading the fuzz virus (which raises the question of who is driving these trains and why they don’t just stop), until you either touch a crystal dropped by a civilian and become your normal self again, or the entire USA becomes fuzzed over and you lose, which takes a very long time. That means you can experience the end of a pseudo-zombie apocalypse in a basically zombified form in which you literally do nothing but watch your character move and hope to be rescued.

Yes, that can happen, as the game and its invasion all play out in real time. In fact, it goes to great lengths to simulate that real time.

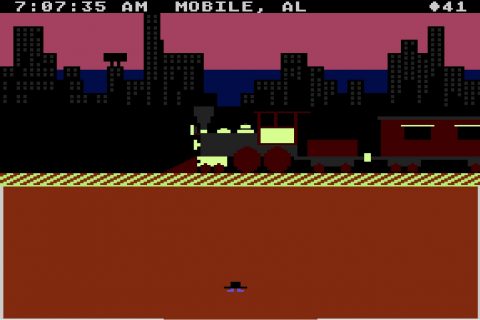

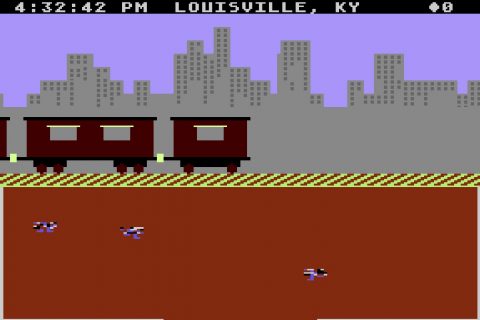

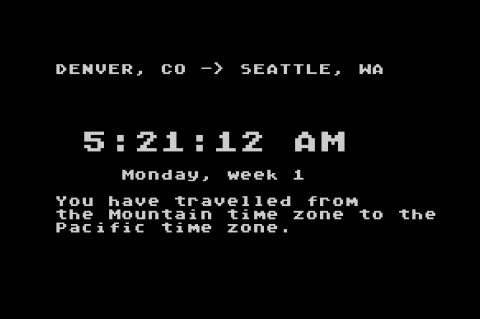

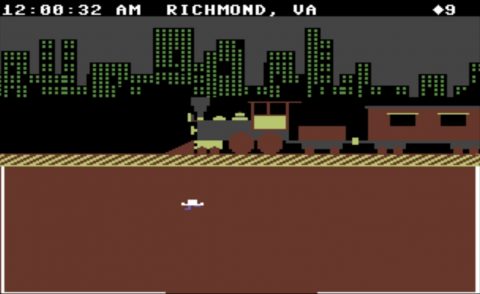

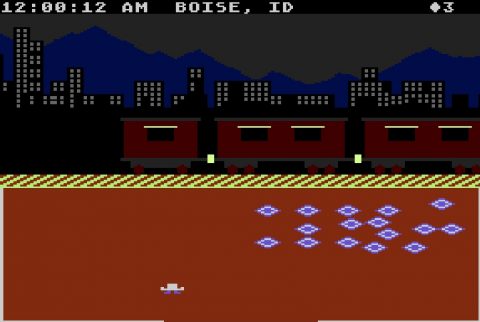

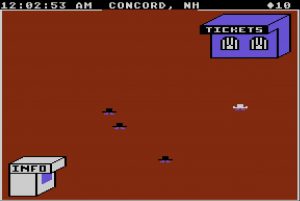

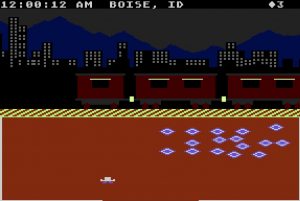

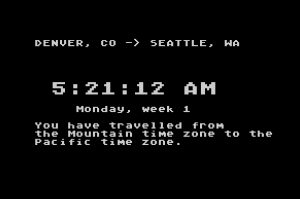

Beginning on Sunday, at 12:00:00 AM, the game’s clock counts second by second. Trains arrive every 15, 30 or 60 seconds depending on the time of day and importance of that city. The clock speeds up rapidly during train rides, with greater distances taking longer than shorter distances, then slows down once you’ve reached your destination. The game even lets you know when you’ve passed across time zones, and adjusts the clock accordingly.

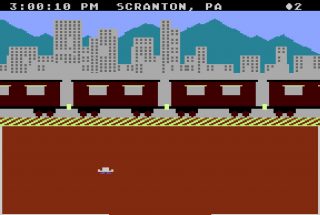

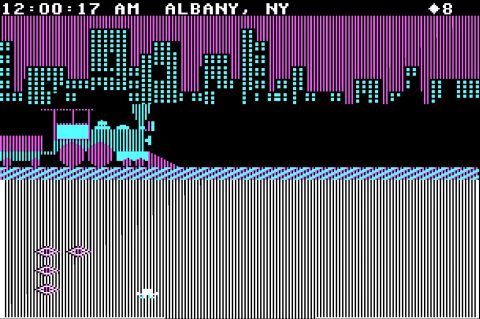

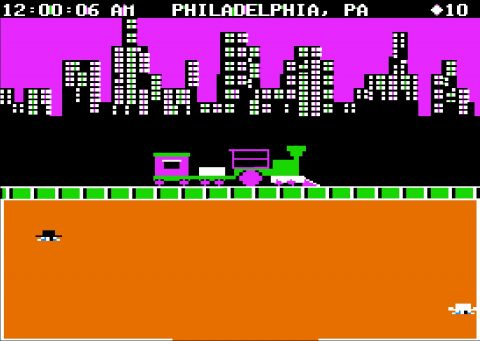

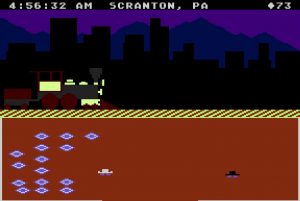

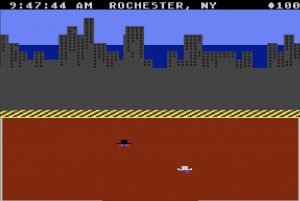

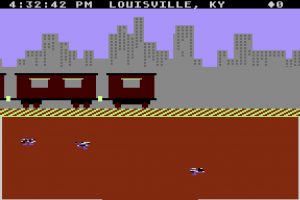

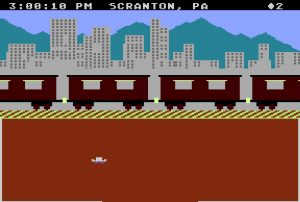

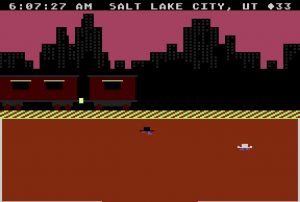

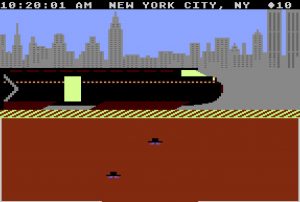

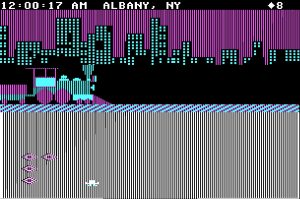

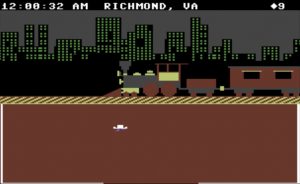

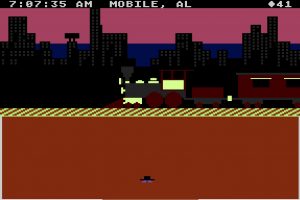

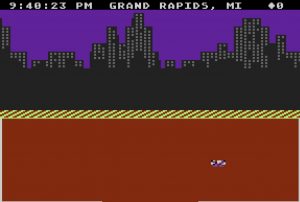

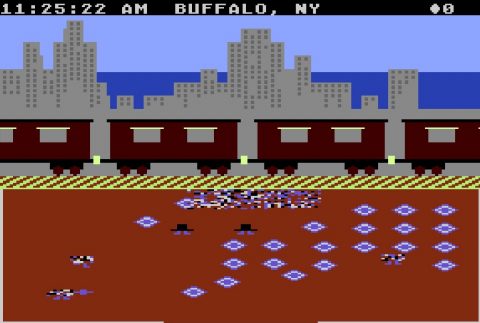

Visually, the game actually portrays each time of day with a different color scheme. Skies can range from different shades of gray, blue or purple to a vibrant pink, buildings can be black or shades of gray, and the windows can be light or dark. Well, depending on the version of the game, as it was released for four different computers of the time, with the Atari 8-bit computer having the most colors and putting them to use. Overall, there are 12 distinct times of day for every two hours and in the Atari version at least, no sky color is repeated.

The same city can look very different at different times of day.

This attention to visual detail extends to the city backdrops themselves, with New York City having recognizable landmarks (including the twin towers that were destroyed in 2001), and cities that are in mountainous regions or near the ocean having a mountain or ocean in the background that also changes color with the times of day. Even the gameplay portrays the importance of various cities: trains arrive more frequently in more important cities, major cities have fast bullet trains which only take you to other distant major cities, and capitol cities have information about the real time spread of the FuzzBodies. There is however some attempt to conserve disk space by having multiple cities share portions of backdrops, as some of the screenshots in this article show.

As Scholastic published this game, it was intended to teach kids geography. Let’s just say that many kids learned that New York City wasn’t the capital of New York, when they reached it and were surprised it didn’t have an info booth!

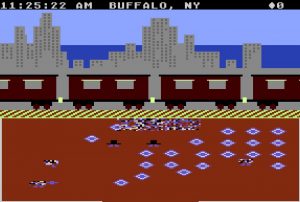

The fuzz infestation plays out in real time. If you’re in a city which is dangerously close to one that’s been “fuzzed” as the game puts it, then if you hang around long enough, you’ll eventually see FuzzBodies getting off the train and spreading their fuzz. You’d better have been planting and collecting those crystals! Sometimes you may even arrive in a city that’s erupted in a big battle: once you arrive and hear the distinct sounds of crystals being dropped, FuzzBodies spreading their fuzz and FuzzBodies being changed back to normal, you know exactly what’s going on.

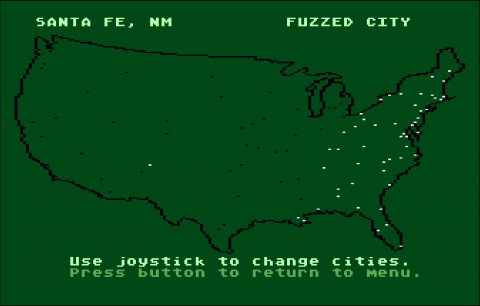

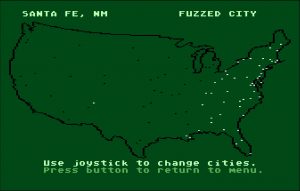

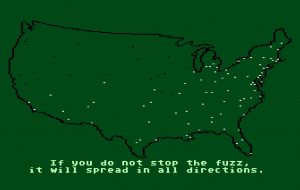

Each capital city has an info booth, which can be entered to view a map with various information. You can examine the location of cities near each other and get an idea of the distance between the major cities of the US, as well as plan out a good path to take from point A to point B. You can see the FuzzBomb’s known location, useful for trying to escape it or get closer to it and hunt it down. And you can even watch a prediction of the fuzz’s spread, showing the cities being taken over one by one on the map. One confusing aspect of the info booth is that the map of all cities lists them as “FUZZED CITY” or instead says something like “4 CRYSTALS” or “12 CRYSTALS” but what the latter means is anyone’s guess. Even the manual doesn’t explain it.

How do you win the game? Make sure you have 100 crystals, go to the FuzzBomb’s current location, and – going completely against the game’s previously established logic – walk right into it. It explodes. You’re then congratulated and told how long it took you to win the game, based on the game’s timer of days and hours. That said, doing this is super hard for one simple reason: as you get closer to the FuzzBomb’s location, you must pass through more and more “fuzzed” cities, and getting through those cities without turning into a FuzzBody yourself is very hard, especially for very populated cities! And if you ever run out of crystals, the only way you’ll ever get new ones is if a civilian drops some, which they only ever do if there’s a fuzz attack. This means you can screw yourself out of a required resource and only ever get it back when in imminent danger.

Making things trickier is the game’s randomized elements that change how each session plays out. You never know which city you will start in or which one will contain the FuzzBomb. Sometimes you’ll start very close to it, and sometimes it could be as far away as the opposite side of the country. There’s a hard mode which begins with a large chunk of the country already fuzzed, which sometimes includes the city you start in! And when you enter a fuzzed city, you never know what exactly you’ll find: will there be a bunch of FuzzBodies everywhere, or a group of civilians bravely fighting them off?

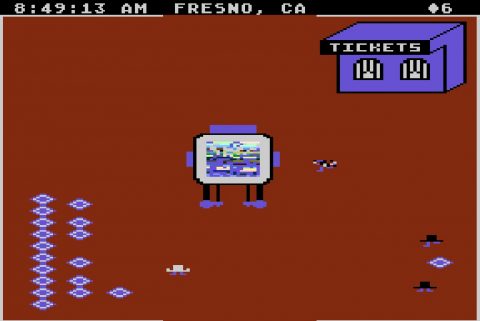

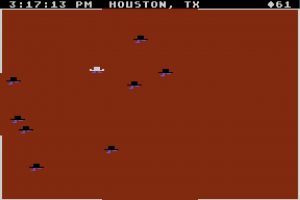

Here, Agent USA has turned into a FuzzBody, and can’t be controlled by the player. The civilians are dropping crystals and running in panic. If Agent USA happens to touch a crystal, the player turns back to normal and is in control again.

Or will the place be nearly empty, making it safe to use crystals to change the few FuzzBodies back to normal and then grow yourself a little crystal farm as a barrier against any new FuzzBodies riding the train in? Good crystal and civilian management is part of an effective strategy to making it far in this game, as is good planning of which cities to go to in order to find the best route to the FuzzBomb. Maybe Scholastic is right: this game does teach geography!

Let’s talk about the presentation. For the time it was made, Agent USA had a very detailed and stylized presentation. The game opens with an intro that explains in great detail how the game is played and what all of its features are. Most games of that era tended to be super simple, considering the limited capabilities of computers and consoles of the time, as well as the inherent simplicity of a controller that literally had only one stick and one button! But the developers of Agent USA went so far as to create a narrated demo that shows most of the game’s features: FuzzBodies walking into crystals and changing back into civilians, Agent USA dropping crystals and then picking up the ones that grew, entering a train, using the info booth and its functions, and even encountering a rare bullet train.

The sound design is limited to a handful of sound effects and a single song. The song is a sort of 1970s-esque spy theme which plays when riding a train, so it’s going to be heard a lot. The sound effects are simple but appropriate, including the locomotive whistle or bullet train horn and the coming and going of both types of trains. Sounds that play offscreen are not only softer but muffled to give the feeling of distance, a super rare effect for the time.

Visually, Agent USA has a character design that’s become synonymous with the game: everyone is represented as a walking hat. You’re a white hat with upturned corners, and everyone else is a black hat with flat corners. FuzzBodies are walking bundles of old-style TV static. And the FuzzBomb is… a giant box filled with static that stands on four wheels and has two eyes.

Cities themselves not only show visual differences in their skylines based on location and time of day, but the actual physical size of the explorable area also varies based on the real life size of the city. In addition to the skyline, each city has a certain number of “screens” that can be walked around, ranging from one to four. Civilians wander around randomly, and frequently get on or off trains. Combined with the game’s sound effect-driven rather than music-driven sound design and its many elements used to simulate taking place in real time, Agent USA is arguably one of the most atmospheric games made in its era.

The Atari 8-bit computer has the most detailed version of the game. The Apple II, Commodore 64 and IBM PC versions have major differences in details such as different or fewer varieties of colors used for the times of day, crackly and worse sound, choppy movement, and even whether or not the FuzzBomb has visible eyes behind the transparency effect of its fuzz. The Apple II version even cuts down the size of the locomotive from a large 4-4-0 American to a tiny Jervis.

Agent USA is a product of the early computer gaming scene, which in a way can be considered the first true indie scene. It wasn’t dominated by a small handful of big companies, nor were computer manufacturers able to limit the output of publishers or developers with licensing agreements. At the same time, while genres existed and conventions were established, games were super experimental. The severe limitations of these computer systems meant that many of the creative ideas indies are making today were impossible, but that meant that many of the ideas back then were both original and very simple.

After all, how many games exist in which you can become “zombified” and literally spend anywhere from seconds to over a half hour unable to control your character until either you randomly get rescued or the world ends? Or run out of a required resource and only be able to find it again when other people are using that resource to protect themselves from an invasion? Modern games are built to be more fair to the player and avoid frustration and wasting their time, but Agent USA commits to its ideas.

That was what games did back in the experimental era before genre conventions and game design theory were more established. We had games like Nautilus with its split screen competition involving a submarine that must destroy an underwater city while a ship tries to protect it. Frogs and Flies with its simple fly eating competition as time slowly progresses from day to night. Final Legacy, which had players juggle attacking enemy ships, destroying missile launchers, shooting missiles out of the sky and maintaining their fuel all in real time.

None of these games would likely be enjoyed by modern audiences due to their sheer simplicity, limited gameplay and design flaws. Agent USA‘s real time simulation of a zombie-like infestation of an America connected by trains is certainly unlike the games made today. Does it hold up? Probably not. But it is an interesting footnote in early computer gaming’s very experimental history.

Links:

The Internet Archive’s copy of the Atari 8-bit computer version of the game, with some visual glitches (controls: F1 is Start, F2 is Select, Num Pad is the controller): https://archive.org/details/a8b_Agent_USA_1984_Scholastic_Wizware_US_a

Screenshot comparisons:

IBM PC

Apple II

Commodore 64

Atari 8-bit