Albion might carry the logo of Blue Byte Software, but you won’t find the people who made the game when looking at the credits of Settlers. The Albion team was composed of former Thalion Software employees – Atari demoscene veterans who turned to game development (usually for Atari ST and Amiga) but couldn’t make enough money to sustain their company despite amazing technological achievements and favorable reviews. Albion is powered by a slightly modified DOS port of Thalion’s Amber engine, created for the RPGs Amberstar and Ambermoon.

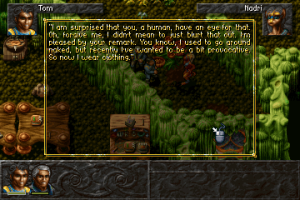

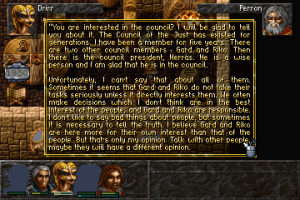

Albion itself is a strange beast: the Amberstar legacy is immediately visible and, like Thalion’s Amiga RPGs, the game approaches many things similar to the later Ultima games: almost everything can be picked up (although most things are useless), NPCs work on schedules, dialog uses both selectable keywords and a simple parser and the playable characters need to keep track of hunger, encumbrance and inventory space. On the other hand, the game seems inspired by the atmosphere, storytelling style and linear structure of Japanese console RPGs.

Albion is a game with a strong focus on narrative and worldbuilding. The story takes place in a future after humanity colonized space and in the process developed the need for an unimaginable amount of resources. To solve the problem, a technology was created that made it possible to excavate entire planets and haul everything valuable across the galaxy. The game begins on the excavation ship Toronto as it prepares to mine a desert planet the crew calls Nugget.

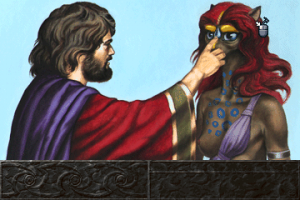

After two of the Toronto crewmembers crash-land a shuttle on the planet’s surface, the game’s science fiction aspect takes a backseat (although it never completely disappears and becomes an important part of the overarching narrative in the second half of the game) to the exploration of Albion, as it is called by its inhabitants. Not only is it not at all a barren desert, but also inhabited by two sentient races: Iskai (cat people) and humans. Probably the most interesting thing about the game is its portrayal of those civilizations.

Iskai live in harmony with nature and use its power to draw magical energy from seeds, but their society is far from a hippy utopia: their rules and taboos can be strange and labyrinthine at times, the laws are based on collective responsibility and Iskai themselves are not strangers to deception or cruelty. Possibly the strangest part of their culture is the Sebai ritual: a dying Iskai can (although the law requires the approval of the Council and a newborn’s mother) achieve de facto immortality by taking over the body of a newborn child. While most Iskai don’t have any problems with this practice, some raise moral objections against it – there’s even a character who refuses immortality despite the Council’s approval.

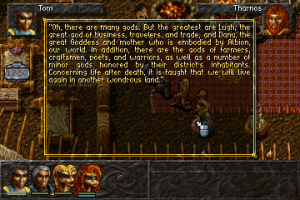

Humans living on Albion have societies resembling the early medieval Celts, although they form a few distinct societies with different economies and government types: there are villages ruled by tribal kings, which survive through farming and fishing, rich port cities ruled by councils and even a mysterious secret society with extremist political views, cult-like approach to religion and a penchant for assassinations. Humans use druidic magic which, unlike the kind used by Iskai, doesn’t require any seeds.

Albion, unlike most other Western computer RPGs of its time, doesn’t allow the player to create any characters. All the party members are predefined characters. The player’s influence on both their development and party composition is fairly limited. Albion’s playable characters are:

Characters

Tom

The game’s main character and the only constant party member. He’s one of the pilots on Toronto. Tom is an all-around decent fighter with the ability to use guns (provided you find a gun and don’t run out of ammo) but absolutely no magic skills.

Rainer

A scientist who crash-lands on Albion along with Tom. Rainer is fascinated by many of the planet’s lifeforms, the fact that humans live on its surface and, most of all, the existence of magic, which goes against everyhting he thought he knew. Unfortunately, he is a terrible fighter with no magic skills. He can use guns, but his long-range combat skills are so low he’ll miss most of the time.

Drirr

An Iskai warrior who doesn’t talk about his past; assigned to accompany Tom and Rainer when they are forced to solve a criminal case due to a certain weird law. He’s not the most clever person around (his carelessness will get the party in trouble in a certain dungeon) but he’s a fast and powerful melee fighter who quickly gains the ability to attack twice in a round.

![]()

Sira

An Iskai mage that got involved in the aforementioned criminal case against her will. Lousy in melee combat and almost competent with bows and thrown daggers, but her true strength is that she’s able to learn some of the most overpowered spells in the game.

Mellthas

Deaf and mute human druid who falls in love with Sira after the two manage to communicate telepathically. Most of the time neither the best fighter not the best spellcaster out there, although he can learn a few spells that, while useless against most of the enemies, kill demons in one hit. Because of their relationship, removing him or Sira from the party will cause the other one to leave as well.

Khunag

An optional party member: a human ‘scholar of magic’. He used to be a part of an evil cult and is a great help when going through their dungeons. Other than that, he’s a better magician than Mellthas but not as good as Sira.

Siobhan

Another optional party member: a human warrior living in Beloveno. She is the most powerful melee character in the game (especially when equipped with an artifact sword) but unfortunately for her, it’s generally agreed that it’s better to take Khunag along.

Joe

A technician from Toronto who joins the party near the end of the game. Generally a bad fighter with no spellcasting ability, but he can use guns at the stage of the game where guns and ammo are quite plentiful. He also has some very good plot-related skills, which make the final areas less of a pain.

Albion’s storyline starts off slow, but grows quite complex over the course of the game. It’s all about the struggle between science and magic, the philosophies behind them and their respective deities: Animenkna and Animebona. This plot can be pretty interesting but generally speaking, the smaller sidequests are far more intriguing and the backgrounds of some of the characters can be more memorable than anything about evil AI threatening nature. The main storyline is also hindered a bit by the typical 1990s environmental soapboxing in the later part. (If you think that cat people, humans gathering resources from distant planet and environmental messages sound like James the Cameron’s movie Avatar but over a 10 years earlier then you’re not alone, some of the game’s developers have noticed it as well.)

The graphics in Albion sometimes show their demoscene roots, but unlike the team’s earlier games at Thalion, it was in certain regards technologically behind its time. Yet the game features a great art direction, which really supports the nature of its setting: the organic cities of Iskai, the wooden huts of the Celts, the cold and futuristic corridors of Toronto. The designs of non-humans are pretty great too: the usual monsters look strange but still resemble wild animals, the demons range from threatening to bizarre and the Iskai have features which, despite low resolution, distinguish one from another and make all of them look like individual characters.

The game has a few cutscenes in the important moments, but they’re generally simple static pictures with occasionally a few frames of animation or a zoom-in effect. They’re nothing special for 1995, but they’re very competently made – the pictures feature a really great use of dithering to create the illusion of shading despite the limited color palette. This extends to everything else about the game’s presentation – it’s well made (and it would have been amazing if released a few years earlier on Amiga like Thalion’s games) but it does nothing to innovate and seems to be working around limitations that simply weren’t there anymore at the time of its publication.

Albion’s soundtrack is consistently, good but none of it really stands out and it tends to get repetitive quickly because of the limited selection of tracks. The music was composed by Matthias Steinwachs, who also made soundtracks for some of Thalion’s games, including Ambermoon – and just like Ambermoon’s soundtrack it just isn’t as great as the music from Amberstar (by demoscene legend Jochen Hippel). The sound effects are serviceable and inoffensive, with a single incredibly annoying exception: there’s a bug that triggers loud, high-pitched and jarring PC speaker tone. If this occurs during a battle, it’s not unusual to hear it every turn.

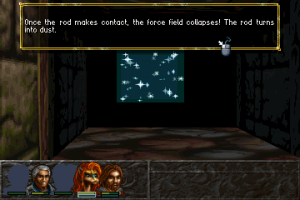

Albion is played from a slanted top-down perspective similar to that of Ultima 6 and 7 (with an either zoomed-in or zoomed-out view, depending on whether the characters are in a building or outside), with the dungeons and larger settlements rendered in first-person view – not a grid-based one with turn-based movement along cardinal directions, but something more akin to Ultima Underworld (although without slopes or any other elevation differences). This works quite well in the dungeons where light sources are limited, corridors are narrow and you usually move slowly and methodically (although looking at the map is still necessary due to the fact that there are not many distinguishing features and textures are very repetitive), but the extremely low field of vision makes navigating through the cities a living hell for those prone to motion sickness.

The game runs in an accelerated daily cycle, which affects the schedules of NPCs and the exhaustion and hunger of playable characters. The former isn’t a big problem because food is cheap, but the latter gets annoying when you can’t find a place to rest in a town or, conversely, are unable to heal your party in the dungeon by resting because they’re not tired. The clock is also used for a few puzzles.

Encountering wandering monsters in either first person or top-down mode switches the game into combat mode. The battles are tactical, with close combat specialists needing to move adjacent to the enemies on a small board, but the turns are resolved in a first-person view. The escape mechanic is interesting, because whatever the player was fighting doesn’t disappear, but instead will try to chase the party, forcing the player to actually run from enemies.

Unfortunately, the combat is easily the game’s weakest aspect. While the battle engine itself is quite good (if a bit slow), the game suffers from a lack of both variety and balance. The former manifests mostly in each location having only a few types of enemies (often with stronger palette-swaps as the level progresses). When the correct way to fight a certain monster is figured out once, it won’t surprise you again. The balance issues lead to the game having no middle ground between very easy (because the player can spam overpowered spells and is equipped with the best gear) and very hard sections (which means slogging through the dungeons, saving all the time, coming back to towns when possible and waiting until you can rest). There’s not much depth to it and unfortunately, the only way to make the hard parts easier is through grinding.

Albion is a slow game and it gets slower as it goes on. The early locations aren’t too challenging, but preparation for the later ones means grinding money to buy equipment, grinding levels to get training points, grinding money again to turn training points into skill increases, grinding even more levels so that Sira can learn her most powerful magic and grinding spell proficiency (by casting spells repeatedly). Spells need to be taught and levels are only a necessary condition – if you leave the first island before learning all of Sira’s spells, you’ll need to wait a long time for the next opportunity. As the game goes on, adequate items become more expensive (equipping characters just with loot from the dungeons won’t do) and teaching spells to characters other than Sira starts requiring money – thus, even more grinding is necessary. Dungeons become much larger, puzzles stricter and backtracking more frequent.

Albion is a fairly buggy game. The aforementioned sound glitch is annoying, but unlike several other ones, it’s not game breaking. On the flipside, some of the bugs make it possible to gain a large amount of money faster than through fighting monsters and gathering loot, so at least some of the grinding can be reduced (not by much though – you still need to grind levels/spell proficiency, and the exploits can be time consuming as well).

The game was released exclusively for DOS PCs. The 2015 digital release is running through DOSBox and has a few problems – the emulation runs too fast when in a city, which isn’t too much of a problem until you’re trying to talk to an NPC and he keeps running past you. The full screen view tends to either get stretched on wide-screen monitors or to get drawn outside of the screen on non-widescreen ones (this is probably because the game has a native resolution of 360×240, which is in a now-uncommon 3:2 aspect ratio).

Albion is an interesting game: a fusion of the highly interactive world simulation style of the late 1980s/early 1990s computer RPGs, the dramatic narrative of Japanese RPGs, the aesthetic sensibilities of the European demoscene and the then-common preoccupation with environmentalism. It’s a unique, very creative world with a lot of detail put into background, history, culture and individual characters. Unfortunately, playing the game to completion can be quite frustrating as the game is slow and grindy even for the standards of 1995. It’s certainly worth playing for its story and setting, but after some time, the tedium begins to set in and many players will not have the patience to go through some of the longer dungeons.

Links:

Albion on GOG

Matt Chat: Albion