Despite rarely being recognized as such, the 1988 presidential election was one of the more influential elections of the modern era. In fact, it was where modern American politics became what they are today. The Republicans adopted Reagan’s anti-government attitudes and carried them further than he did, with Bush opening his bid for the presidency with a call for “a taxpayer’s bill of rights.” “Liberal” saw its first use as a pejorative, and political correctness (or, rather, rebelling against the mere perception of it) was just starting to emerge. The Democrats responded to these developments by beginning their drift to the center, which would be solidified four years later under the Clinton administration. The 1988 election is also when Super Tuesday became what it is today, even if this wasn’t the first election to have a day like that. In light of all this, it only makes sense that somebody would make a game about this election.

What makes a little less sense is that a Japanese video game company would be the ones to make that game, and as the election was still happening. Enter America Daitouryou Senkyo, Hect Co.’s foray into the world of strategy/simulation games. This game was the product of a different history. While this wasn’t the first strategy game Hect Co. ever made (they published Shogun a few months prior to this), the company had largely only worked on action games beforehand, meaning this was likely their attempt to cash in on the popularity of the simulation genre. Or maybe it was the product of director and future legislator Shintaro Ito’s interest in politics. So why didn’t they make a game based on the Japanese electoral system? Putting aside the fact that the latest election in Japan had wrapped up while primary elections, made for a more interesting design challenge.

On the one hand, this makes America Daitouryou Senkyo an interesting look at how Japanese culture (or at least this one game developer) may have envisioned the American political system. On the other hand, it’s a definite product of its time, which proves to be a double edged sword. Although its emphasis on systems and processes above all else lends the game an optimistic tone, it also limits that game’s scope in a way that sometimes does more harm than good.

The game’s basic premise shouldn’t need any real explanation. You choose which one of the six candidates you wish to run as, and then campaign across America in a bid to win the presidency. Playable candidates include:

George H. W. Bush (Push)

64 years old, blood type A. From Texas. Current (soon to be former) vice president. Moderate Republican, WASP. Supports free trade.

Margaret Thatcher (Sasha)

62 years old, blood type O. From Michigan. Former Senator. Conservative, nicknamed “The Iron Woman.” Opposed to a strong Japan.

Pat Robertson (Robert)

59 years old, blood type AB. From Virginia. Televangelist, ultra conservative. Member of the New Right branch of the Republication party. Anti-communist.

Michael Dukakis (Dekakis)

55 years old, blood type O. From Massachusetts. Former Massachusetts governor. Moderate Democrat, Greek. Strong support from labor unions.

Jesse Jackson (Zackson)

47 years old, blood type B. From Illinois. Pastor. Liberal, African-American. Years of experience working in the civil rights movement.

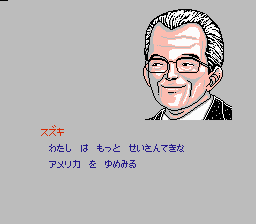

Suzuki

51, blood type A. From California. Former Senator. Conservative, Japanese-America. Member of the agricultural committee.

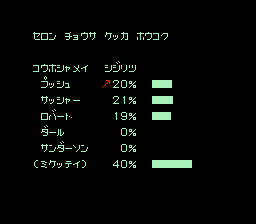

(Note: There are two other candidates running in both parties (Dole/Sanderson for the Republicans, Gore/Schrer for the Democrats), but neither of them are playable. They only serve as opposition during the primary election phase and potential vice presidential candidates during the general election phase.)

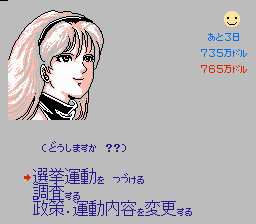

In addition, you’re prompted to select one of four assistants to provide support during the campaign. Unlike the candidates, the assistants aren’t limited by party lines.

Alan

Blood type AB. Originally worked for an agency. Specializes in marketing and polls.

Scott

Blood type O. Originally worked for the state department. Has an ear for fiscal policies.

Penelope

Blood type A. Originally a television correspondent. Fluent in five different languages.

Basil

Blood type B. Originally a newscaster. A well informed person.

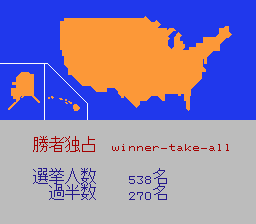

No matter who you choose, though, the campaigning process ends up being the same. It also ends up being so full of little idiosyncrasies that America Daitouryou Senkyo becomes less of a representation of the American political process as it is an interpretation of that process. For one, primaries get far more focus than the general election. Most of your campaigning occurs on a state-by-state (or voting-bloc-by-voting-bloc, in the case of Super Tuesday) basis, whereas the general election is just a single event at the end of the game. Those familiar with the American political system may think this an odd choice. Not only do primaries and general elections receive about the same amount of media coverage in a given election cycle, but this format also seems to emphasize campaigning within a given party above all else, maybe even to the point of treating the larger population as an afterthought.

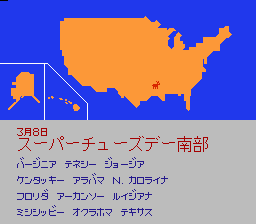

In practice, it’s difficult to tell how much of a problem this actually ends up being. Whether or not it is a problem, facets like these are products of the game’s process-oriented approach to the electoral process. America Daitouryou Senkyo couldn’t care less about individual candidates or political beliefs or any other factors in the election. All it wants is to see the electoral process unfold, and to that end, the developers designed a set of systems that would allow them to venerate those processes. Returning to the primary/general divide, it’s a format that lends itself well to tense moments and dramatic arcs. Super Tuesday provides the first such moment in the game: for an event that’s known for removing less viable candidates from the running, it feels appropriate that this take on it is challenging enough to bring most playthroughs to a screeching halt. Likewise, it’s hard not to feel invested in the final moments on election day. Tension mounts as the results of the election come in state by state. All your hard work has led to this moment, and you spend the whole time hoping that it pays off; that you cross the 270 vote line before the other candidate.

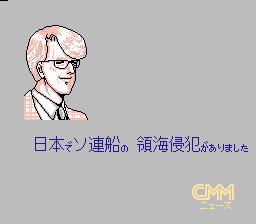

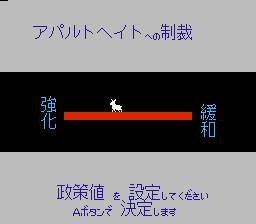

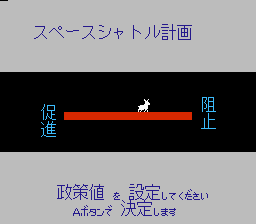

This level for admiration ends up defining nearly every aspect of the game. It shows itself in the tone, whether that be the hopeful look on the characters’ faces (assistants especially) or the calm, somber music that plays all throughout. It shows itself in the level of research that went into the game’s production. This doesn’t just apply to what goes into the game – obvious topics like gun rights and tax cuts and military spending exist alongside more obscure ones like the Star Wars missile defense system (yes, the game actually refers to it as “Star Wars”) – but also to how those elements are implemented. All the tiny variations in how a given policy is received imply differing political cultures on a state-by-state basis which you’ll be forced to understand if you want any chance at success.

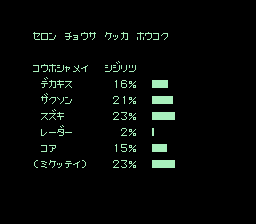

But most of all, that respect shows itself in how mathematically focused play is. Like a lot of these kinds of games, much of what you do in America Daitouryou Senkyo boils down to managing numbers. You maintain a budget; you check poll numbers; you check demographics and records; you decide how many units left or right you stand on any three policies (out of 48, spread across six categories); you choose how many public appearances you’ll make; and you set amounts of money to be spent per state and per channel on political ads. For a lot of people, gameplay like this sounds unbelievably dry and tedious. At its worst, playing the game feels like carefully managing an Excel spreadsheet.

Still, as a piece of political commentary, the game communicates a certain level of trust in the efficacy of American politics. For all its quirks and irregularities, the American electoral process can ultimately be reduced to a set of perfectly understandable mathematical rules and variables. Even when surprises present themselves, like current events changing public opinion or political factions calling you and promising to donate to your campaign if you support their cause, they never threaten to disrupt the system, as it’s built to accommodate them. All in all, you get the feeling that whatever thoughts the developers may have for this specific campaign or those participating in it (they never say much about either), they believe the larger system works, or at the very least, that anything preventing it from working can be easily identified and dealt with.

That isn’t to say there aren’t problems in in this version of America, because there are definitely problems in this version of America. America Daitouryou Senkyo is a game that bears the assumptions of both the American political systems of the time and of this particular election, for better or for worse. For example, there’s no place for any policies left of center. Even running as a Democrat, conservative policies like curtailing civil rights or cutting taxes tend to be more successful than their left-leaning counterparts.

Add in the mathematical impossibility of certain candidates ever getting the nomination (poll numbers are almost certainly fixed upon entering a state and some states vote completely outside your control), and you end up with some accidental political commentary. The system is beyond affecting, the game says, as any candidate who even considers challenging prevailing political views will be swiftly punished for doing so. Successful campaigning has less to do with the integrity of a candidate’s beliefs as much as it does their ability to match a given political climate. As dismal as all this may sound, it may make more sense to interpret this as political realism rather than cynicism. All America Daitouryou Senkyo does is depict the American political landscape as it is, warts and all, meaning these criticisms have more to do with the systems the game follows than they do the way it follows them.

Yet while it would be unfair to criticize the game for what it acknowledges, it’s perfectly fair to hold the game accountable for what it doesn’t acknowledge. Superdelegates don’t appear to play any role in the Democratic nomination process, and which assistant you pick doesn’t affect your campaign in the slightest. But in the grand scheme of things, these are minor problems. More worrying is the utter lack of a human element in this game. Anywhere such an element may exist, it’s nowhere to be found. The expectation that candidates succeed on policy eclipses whatever personality those candidates may have, reducing it to a few stock lines before each phase of the primary and a short speech at the convention. And while the news plays a significant role in the game, it isn’t designed to address what role the press may have in supporting or undermining candidates through their coverage because none of the coverage you see has anything to do with the candidates themselves. And where are the debates?

These aren’t trivial concerns. Without that human element, the game can’t address how these systems are used in practice, meaning it can’t consider (much less respond to) potential abuses. For example, it can’t respond to a situation like the 2016 election, where a candidate who espouses xenophobic ideologies and calls for violence has become a serious contender in part by ensuring that any news outlet that covers his statements gets a significant boost in ratings. Or, responding to something America Daitouryou Senkyo could have predicted for, the game finds itself unprepared to acknowledge that voters may be convinced to vote based on fear instead of reason, sometimes to the point where they’ll vote against their own interests.

Rather than being confronted, these problems are instead obfuscated; explained away as something that only happens when politicians act in bad faith (which none of the candidates appear to do here). Topics like these may be uncomfortable to tackle, but if the game wants to hold true to its admiration for American politics, then it has to confront faults like this for what they really are. Otherwise, it can’t really claim to represent the system it claims to be represented. The idealism that’s so central to the game’s premise turns into naivete at best and willful ignorance at worst.

Take political ads, for example. Although America Daitouryou Senkyo is aware of their existence, it never says much about how they’re used. You never see them and (presumably) other candidates’ ads never affect you, so if you were take the game at face value, then it would be safe to assume political ads play only a marginal role in any presidential campaign. So what about the the Willie Horton ad, which was definitely a factor by the time the game was in development? That ad represented a significant milestone in the Bush campaign, since he was able to score points against his opponent by claiming Dukakis was soft on crime. Yet he was only able to do so by appealing to white voters’ fears of black crime/violence. The ad represents an ugly moment in American history, both drawing on a long tradition of dehumanizing African Americans and foreshadowing many other acts of dehumanization that continue to this very day. America Daitouryou Senkyo is ill equipped to handle subjects like this.

In the end, the game is ultimately unable to internalize some of the nuances of the American political system, even if it is aware of them. Still, thirty years after its release, America Daitouryou Senkyo remains an interesting little game. In applying Japanese simulation game sensibilities to American politics, the game foreshadowed the electoral simulation games that would emerge in the 1990s and proliferate in the 21st century. And even ignoring that, it’s still an intriguing historical artifact. How many other contemporary video games directly represent political institutions in how you play the game?

Links