Before creating the Syberia franchise, Benoît Sokal cut his teeth in the world of game development with Amerzone. Based on one of his older comics, L’Amerzone (which had a significantly darker ending), Amerzone is the first major popular release developed under Microïds, selling over a million copies on first release. Looking back at it, you can see the pros and cons of the later Syberia series taking form. They all stem from Sokal’s inexperience with game design, which does show up in this release – but not as much as you’d think. For a newcomer, Sokal proved he could do something impressive with the graphic adventure genre. It’s mechanically simple and plays to his strengths as a storyteller and comic artist, and he had a refreshing focus on making the game approachable to wider audiences.

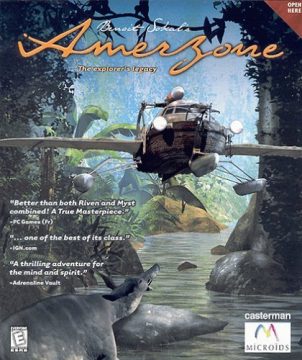

Amerzone casts you as a faceless, voiceless journalist. You learn of a past expedition explorer Alexandre Valembois went on to Amerzone, a small country currently ruled over by a dictator. Valembois betrayed the people of Amerzone when he stole an egg belonging to legendary white birds, sacred to the country, and tried to find success back home with this discovery. This failed when no one believed him on the true nature of the egg, but he kept the egg for decades and looked after it, realizing the birds within were still alive. After he dies upon a visit, the player character decides to take the egg to Amerzone and hatch it, using Valembois’ amazing Hydrafloat, a mechanical wonder of a vehicle with multiple forms, and fulfill his life ambition and dying wish.

Like Syberia, there’s a surprising lack of conflict here. The journalist’s story is just bringing closure to the people from that horrid expedition. All those grudges and pains are already dying off – literally. Just about every major player from Valembois’ time die as soon as you meet them, or are already dead. You don’t even get to fight that dictator when you finally meet him. However, that lack of conflict in the here and now fits the themes of the story. It’s a story about both life and death, as you have to watch old men filled with regrets dying without joy or satisfaction. We see fallout of the mistakes they made, and the motivating factor ends up just trying to give their stories a proper ending. The birth of the white birds is both to give the people of Amerzone something to believe in again, rekindling their hope, and bringing an end to the personal stories of the three men and Valembois’ love.

Playing Amerzone is sort of like going through a museum. Every screen and setting adds to a narrative, carefully arranged to get to to reflect on everything you come across. The first chapter has you exploring Valembois’ lighthouse and learning more about this man, seeing just how serious he was in setting things right through exploring his intricate contraptions and systems that make his home. We get an idea of how alien Amerzone is in the second chapter, as we see the last remnants of regular life mixed with ruin and wildlife. The third chapter shows us the results of the selfish actions of Valembois and his former friend turned dictator, including one haunting extra monologue you can listen to at the bar. Even when you start exploring the jungle and see less human life, you’re still learning more about this mythical place and the natural life that the dictator tried to erase in favor of scientific progress. It’s a quiet, reflective game, telling a strong story with very few human characters or bits of dialog. Also must point out that the acting here is far better than most Microïds games. There’s still some cheese to be found, but Sokal’s script is so strong at points that you hardly notice. Even the most cartoonish voices can’t ruin some of these sentences.

Late 90s/early 00s 3D character models are a pretty significant issue, looking horrifying at moments, but they have a more interesting style and sense of expression that something like Necronomicon. The team also had the bright idea to hide them heavily in shadows, which both hides the poor quality of the models and adds to the atmosphere. The rest of the game simply looks gorgeous for the tech at hand, even overcoming poor resolution issues at times through sheer variety and environmental detail in each screen. Credit also has to be given to the animals on display, a mixture of real creatures and fantastical beasts. Even the white birds somehow manage to be magical, despite looking like seagulls, once you see how they’re born. The game holds up remarkably well, mainly through art direction, and the soundtrack fits well with it. It’s low key, with moments of whimsy mixed in.

As for the game part of the equation, Sokal wanted to make something more approachable for players, something that could be experienced, played and beaten with little issue. He arguably went a bit too far in this angle. The puzzles are pretty simplistic, outside trying to learn secret codes in letters at a few points, and other segments feel like they’re missing something. There’s a moment in the third chapter where you’re imprisoned by a soldier that’s over as soon as it starts, and a later chapter has you grappling between rocks that lacks any sort of challenge or need to think. You just find the rock, click on it, pull a lever, and go. The lax puzzles help keep the narrative at focus, which is nice, but they sometimes feel too simple for their own good. Even Sokal admits he was a little disappointed by this and promised to do more if he ever made a sequel.

Amerzone is an overall good game and an interesting piece of graphic adventure history. So much of it holds up to modern eyes quite well, and it has a maturity to it not often see in this genre. It’s a short, cheap game absolutely worth experiencing. Despite its shortcomings, it’s kind of remarkable for being a work so strong for someone so new to the medium. Amerzone is simple. It says what it is upfront, has no real surprises, but manages to draw one in despite. That’s a rare quality worth celebrating.