- Another World / Out of this World

- Heart of the Alien: Out of This World Parts I and II

During most of the ’80s, the real hotbed of game development was primarily Japan and the US. The Atari 2600 kickstarted the home console business in the late ’70s and with it, gaming skyrocketed into mainstream and the homes of thousands. With this new popular entertainment device came a lot of both creative and unforgivably bland products by American developers. When the video game market crashed in 1984, it took the Japanese Nintendo to resurrect it with their Famicom\Nintendo Entertainment System console which showcased their technical superiority and vibrant creatively.

One continent lurked in the shadows while the other giants continued to push the limitations of the technology to seemingly never ending limits. Europe didn’t clearly showcase its potential until the later parts of the ’80s with companies like Rare, Ocean, System 3 and Rainbow Arts putting out some of today’s biggest cult classics across the Commodore 64 and Amiga. Because of the dominance by Nintendo and Sega in the home market, these titles didn’t have the same reach in North America as it had in Europe where the home computers had a much more solid user base.

France in particular had and still has today a very interesting take on the entertainment medium in general. In the late ’70s the anime Goldorak (UFO Robot Grandizer) took France by storm and made Japanese animation and manga into the most popular form of entertainment in the country. While the American entertainment industry has always focused on the bigger blockbusters and Japan always striving to give their games heart and clear life philosophies for the audience to digest, Europe offered a unique blend of both worlds while offering a very distinct imagination based both on the long strong history of society and mythology not found in the relatively young history of America and the closed society of Japan. One man might have proved this better than anyone else with one game alone.

Eric Chahi

In 1983, this young French student started working freelance and creating his own games on the ORIC 1 and Amstrad CPC. It was on the Amstrad that he gained the interest of bigger developers with his release of Le Pacte (The Pact) which included many groundbreaking elements for a text adventure at the time with a Day\Night cycle, an Insanity meter and an engaging storyline which drew players in. After releasing a handful of games on the Amiga for the developer Chips, he soon found himself working for the up and coming Delphine Software on the title Future Wars. Through both frustration and enlightenment, it would be his work on this title that would inspire him to make his biggest game and the most important European game ever released.

When working on Future Wars, Chahi became increasingly frustrated doing only graphics works on someone else’s vision and story. Having come from a background with complete control over his output, he felt the process was too limiting and unsatisfying and even though he was offered a spot as a graphic designer and animator for Delphine Software, he soon lost inspiration and ambition to work on games through other people’s ideas. This would all change when Chahi got his hands on the Amiga release of Dragon’s Lair. This version of the game was quite remarkable for being able to bring home the full motion video laserdisc game onto an affordable storage medium, 6 floppy disks in total. Having always wanted to make a proper cinematic experience through video games, technology finally seemed to allow this to become reality.

From his past experiences with graphic coding across platforms, the decision was early made to employ vector graphics and polygons because of the resource efficient nature of the techniques. After a few weeks coding on his Atari ST, Chahi already had his graphic engine up and running and all that remained now was to bring the pieces of the puzzle together. Through a conversation with the French director Costa Gavras where Chahi revealed a few details on his new project, he came to the realization that the best approach would to not plan any story elements before actually starting work on the levels, but rather draw on his subconscious thoughts and natural emotions to the ever expanding visuals he was creating. While Chahi had set his goals on making a science fiction adventure game with similar style to that of Karateka and Prince of Persia, most of the content was all from improvisation and ideas springing to mind during the work session. In fact, the only thing that was made clear before development was the introduction movie, and that the game was to use a combination of puzzles and action.

Distancing himself from friends and family in order to become completely consumed and to let his inner feelings, fears and total seclusion take over his young mind, Chahi properly put himself in the shoes of the hero to be in the game he was crafting. It would take almost 2 years of constant work out of his basement to complete the game all by himself. In November of 1991, Eric Chahi finally released Another World on the Amiga. To avoid confusion with daytime American soap opera Another World, it was titled Out of This World in the US market (which in turn accidentally associated it with a different television show, a lousy sitcom), and Outer World in Japan.

Another World‘s plot revolves around Lester Knight Chaykin, a young scientist who is teleported to an unknown world when an experiment goes terribly wrong due to a lightning strike while in his laboratory. In a blink of an eye he suddenly finds himself deep underwater swimming for his life to survive and as he gasps for air and slowly comes to, he quickly realizes that he is far from safe, and far from home…

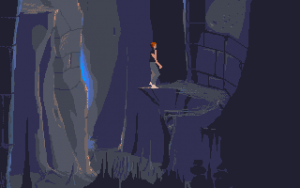

The introduction to this game is incredibly creepy as the music sends chills down your spine and even though all the elements seen on screen are somewhat familiar to us, the experiment and technology is far too advanced for the common man to understand. So the only thing we can draw an immediate relation to is Lester since he is seemingly a completely normal young man, lanky, plain. The opening cinematic was quite amazing for its time, offering cinematic camera angles and impeccable attention to detail which stood out leaps and bounds from the often redundant pictorial introductions that can found in other games released during the time period. As soon as Lester is teleported into the game has started, and here you get your first glimpse of brilliance in this game. There is no HUD to be seen, no scores to be acquired, no indication that the game has started, the only thing you see is Lester floating in the deep. On the top of the screen you see trickles of light on the water surface, while on the bottom there are what seem to be tentacles reaching for you. You draw from your natural instincts and swim up as fast as you can towards the light, towards the surface.

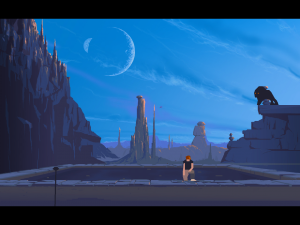

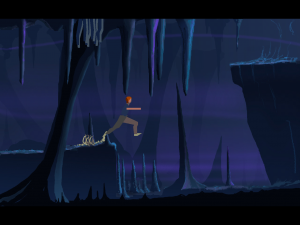

And the entire game is played through these instincts, the reaction to what you see on the screen and what it triggers within you. Another World itself will never tell you or teach you anything. The first stage takes place in a mountain area completely barren of anything resembling human life. In the far distance you see a black shadow run out of the screen, creating suspense in that you know something is there, you just don’t know what…yet. When you start walking you’ll see small leeches on the ground crawling towards you which you can either kick or jump over depending on what you choose to do and when you finally reach the end you’re confronted by the beast, where the only reaction is to run in the opposite direction in sheer desperation and absolute panic.

The graphics only enhance the desperate state of panic. Through the use of polygons, the game has a very clean simple look with little detail to the objects. Because of this, you are left to draw your own conclusion about where you are and why it’s there. It’s through this simplicity though that the game becomes so incredibly detailed, because by giving you so little, it leaves so much room for you to envision the purpose and to speculate on the situation. With so little direct given detail, you create perhaps one of the most detailed game worlds you’ve experienced. All the animations are done by rotoscoping, a technique popularized by Ralph Bakshi in Lord of The Rings and introduced into gaming by Jordan Mechner in Karateka and Prince of Persia, where actual live action footage is traced with animation frames to create a lifelike flow. A lot of details was put into all aspects of the animation as you can see with the beast. While the create itself is virtually just a black blob with 2 red dots of eyes, the movement creates a visual of muscles and flesh with visceral brutality, leading you to see the beast as much more than what given to you visually on screen. It’s speed, size, it triggers your internal human instincts, making you fear it and sense the immediate danger, this is a strong and extremely dangerous animal and Chahi makes use of primal human psychology to illustrate it, making the black shape a manifestation of the inner view we have of a monster. For those who played the game when it was new, most would tell you quite honestly, being chased by the black beast still brings a chilling feeling down our spines and it was a moment where we felt real fear, not a cheap scare or excessive gore, but real deep rooted fear.

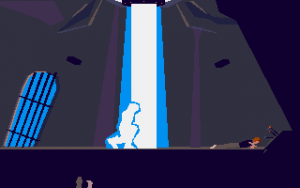

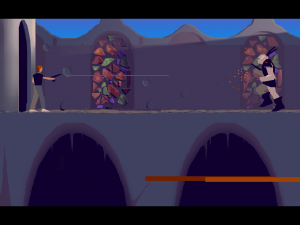

Lester isn’t completely defenseless in his journey through the unknown world he has been thrown into, nor does he remain alone. While during the first stage, all you have at your offensive disposal is a nervous kick to rid of deadly leeches, the action greatly expands its horizons as Lester comes in possession of a gun. This mysterious gun beholds an amazing power which will prove essential to Lester’s progression through the alien terrain. Its use is not only aggressive but also defensive, as well as practical. The default action of this alien utility is a simple laser, which upon contact with living organisms will engulf it and only leave behind bone ashes of the deceased. By holding down the trigger, Lester unlocks the amazing capabilities this gun beholds. Once energy saves up, a ball of energy appears at the end of the barrel. At first this energy ball is rather small and by releasing it, a small force field will appear. This temporary field is a protective barrier which will repel any laser shot in Lester’s direction. By holding down the trigger for a longer period of time, the energy ball will become greater and releasing it will unleash a giant beam of incredible force. This beam can break through walls, shatter large boulders and penetrate the force fields. This massive force beam will drain your gun however and must be used sparingly and strategically, because once drained there are no more power left. At certain points in the game you will find recharge rooms to re-power the energy cells and you once again have the ability to fire and protect yourself. The deadly force beam has a very similar appearance and power to that found in Dragon Ball Z, more specifically the Kamehameha which serves as the most devastating move Son Goku, the main character, has at his disposal. Chahi has admitted that during the time of development, his only other hobby was to read Dragon Ball manga when taking breaks from coding.

Most important to Lester’s aid, and perhaps the most interesting aspect to this game, is the friendship he finds early on in the story. After being chased by the unknown beast through the wastelands, the red headed man finds himself seemingly saved by a pair of cloaked beings, towering over him with great size and presence. The nature of these men is quickly uncovered when they shoot Lester with a sedated shot and imprisons him in the mines. It is here that you meet your ally and best friend. The nameless friend (who was later given the name “Buddy” by Interplay, but the name is disowned by Chahi) is caged along with Lester as he comes to from sedated sleep. He is stripped of any striking facial features or detail, essentially a walking gray sheet for the viewer to draw out. It’s through gestures and body language that you instantly feel a sense of companionship to this individual. There is no distraction through facial expressions, he has none, no confusion of intent, he always aids by guiding you through a world he knows so well. It’s really this dynamic that places this game in a completely different league, not only compared to its contemporary competition but also games released in today’s marketplace.

The game never makes use of dialogue to tell its story, never writes out a narrative for us to follow a direct way to view or digest the story, it only makes use of the world within it. The flora and fauna, sounds and environment, what we see and experience develops the entire story and relationship between the characters and the players, and not a single word is ever spoken. Lester is thrown into a world of unknown filled with dangers, emptiness and turmoil. The players cannot strongly attach themselves to anything in this place, but when we meet the alien companion, we start seeing something very familiar to us; trust and friendship. In such a bleak and depressing situation that we find ourselves in, we clutch onto these familiar feelings and develop a strong bond and care for this friend, which becomes very evident as the game throws emotional triggers and challenges at us. When the alien is in danger, there’s a rush of panic to help him and save him like he has saved you, when you are separated and cannot see him, he is a constant in your mind with questions of what he is doing, if he’s okay, your mind is filled with worry and care. It’s baffling to look at the games of today with the incredible budgets, real life graphics, recorded dialogue and double digit amounts of hours required, they seldom manage to incite any true feeling of care or immersion, but this game not only manages to connect us deeply emotionally, but also provides proper character development without a single piece of dialogue and does so in under 15 minutes – all this from a game made by one man. It’s a true testament to the genius of Chahi and proof that a game is not always restricted to being “time wasting” hobby, but can be a work of art that provokes our imagination and emotions.

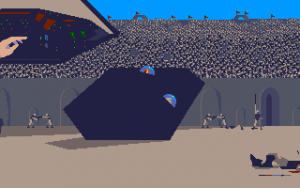

The game is relatively short, even for its time. With some practice, the game can be finished under an hour or so and follows a strictly linear structure to follow. While the first location is a barren wasteland, you will eventually find yourself roaming through the prison camp, caves, mansion resort, a coliseum and even a bath house. As noted, the game offers no narration as to what has happened, but it is made clear through backgrounds and scenarios that there is some sort of oppression that is put upon a certain race of people in this world, as they are used as slaves and fodder for the brutal games that takes place in the coliseum. Chahi himself never gives interviews to speak about the game and has stated that there is no official story to what you see on screen, it is all up to the viewer to craft their own take on what exactly is going on. The ending really cements this idea, with it providing little to no true explanation to where you truly are and what will happen. It’s all left for the player to answer. Some found this ending to be frustrating and overly pretentious, claiming that it didn’t provide sufficient closure to close out the experience, while others found it mesmerizing and artistic with its demand for interpretation and viewer involvement. The game also contains very little music, relying on sound effects and ambience to set the proper atmosphere and life into the picture. The sounds and music was all composed and implemented by Jean-François Freitas, a lifelong friend of Chahi.

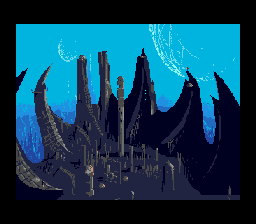

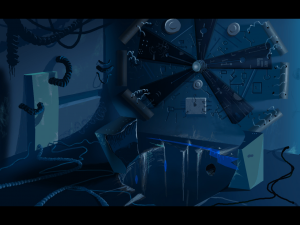

The presentation is truly unique, and still to this day retains a special aura not often replicated. Making use of vector and polygon graphics, it not only allowed for an art style unseen to gamers, but also screen-filling objects with fluid animation. Despite having no words, the game is undoubtedly cinematic, with careful attention to lighting and shadows, and the cut scenes are directed with cleverly placed camera angles. The environment has a shade of blue constantly flowing through it, lending itself to a subconscious feeling of depression that never truly leaves you. The feeling of solitude is constantly reminded as small glimpses into an unknown world is given to us, with a look out the prison window will give you a view a panoramic view of the alien world you have been transported to. There’s a constant feeling of darkness, with dark corridors, confined spaces and air ducts and caves always putting you in a state of claustrophobia and frantic suffocation from your surroundings.

There are also moments in the game that separated it from every other game at the time, giving the player an early taste of controlling a cinematic action piece with their controller. The most memorable scene for many is the one that takes place in the mansion resort. Lester is knocked off screen by a guard and lifted by his throat into the air. Your gun is now on the other side of the room, and it’s immediately clear that Lester is in quite the predicament. When you instinctively click the button during this, Lester will give a well-placed kick into the groin of the alien guard, and is dropped to the floor. You then have to run over, do a roll to pick up the gun and shoot the downed guard as quickly as possible. While it in writing sounds like a lot of motion and rather complicated, it comes quite naturally with the whole presentation of the game. There is also a noteworthy stage which takes place within the cockpit of a tank in the coliseum grounds. Dealing with alien technology and no way of knowing how it works, the only logical thing to do is to mash buttons until something, anything at all happens, and that’s exactly what you do. The animation is fluid and consistent with Chahi recording all actions himself with his camcorder before rotoscoping the footage.

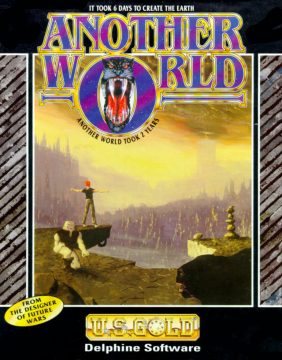

Its artistic content is not limited to the in-game product however. Chahi always had a strong passion for doing illustrations, particularly those in the science fiction genre. He had grown frustrated with the lack of control on how the games he had earlier crafted would be improperly promoted through the box art and product presentation. When Future Wars was finished, Chahi had lobbied himself to do the artwork for the cover but would not be permitted by Delphine, the publisher. It was the disappointment from this that would be the initial spark to create his very own game independently from any guidelines or demands from the business suits. The painting he made perfectly illustrates the game, with Lester battered and torn on the edge of a cliff looking out on the vast alien landscape, completely engulfed in the oppression and darkness of the unknown world while the alien is looking out for danger. Even though this beautiful piece of art was used on the Amiga and PC packaging, it would be changed on many of the international releases to a stock look more in tune with the other titles on the market.

When one looks at the game itself, stripping it of all cultural and historic significance, you might find that the game isn’t as smooth as its art and atmosphere. Indeed, the controls are legit cause of complaint. Drawing its inspiration on Mechner’s work, the controls and maneuvers are quite similar to that found in Prince of Persia in particular. Lester can carefully stroll at a cautious pace or run to escape oncoming danger or gain extra launch in his jump. The leap comes handy as environmental dangers come from all places, even the floor. The player is given an unlimited number of lives and encourages a trial/error approach by giving you checkpoints throughout the levels. The alternate world is not a safe one, and death lurks in every single corner. Deadly leeches, wild beasts, seismic hazards, plants, trigger happy guards, you can be sure that Lester will become an pile of ash more than once. The controls are bit loose which causes some trouble with timing and precision. Especially underground, you will find many pits and plants that will kill you upon impact. Lester’s jump is an awkward leap which is hard to truly predict, and the window for error is very slim, meaning that at near pixel to pixel connection, you will die if you touch the danger in front of or below you. The game doesn’t scroll and makes use of scenes, so with your quick run it’s not uncommon that you will run into the next scene and be quickly disposed of due to Lester taking too long to stop running and prepare his gun. While far from a bad game by any means, its basic qualities are a bit uneven when analyzed by itself.

Another World is also one of the earliest games to include specific death animations or death scenes, in which Lester is killed off due to the different hazards he fails to overcome. Everything from leech bites, decapitation, impalement, drowning or fatal beating can be triggered and gives the game a rather unsettling element to its treatment of death, rather than just simply treating it as a mere setback in the player’s progress. This would eventually become a very popular feature in video games, especially those in the survival horror genre.

When released in Europe, the game was an amazing success. The majority of the game magazines at the time would run multi page features previewing and reviewing the game, giving rewards of best game of the year and highest rated game in history. In France it would win the prestigious Tilt D’ Or award for best game of 1991, while in the rest of Europe, it would be hailed as a masterpiece and embraced as a true showcase of the difference in European ideology and artistic design. With the massive success seen on Amiga, publishers were eager to bring the game not only worldwide, but across different platforms as well. As a result, Another World has seen more than 12 versions since its release.

The first version was the Amiga, which was the birthplace of game. This version is the most unpolished with few checkpoints and stiffer controls. An Atari ST port would soon follow which was near identical, with lower quality graphics and sound being the biggest difference maker. The one thing that sets the Atari ST port apart from the others is during the beginning of the game, as Lester swings on a vine to avoid the monster, he can be heard yelling in fear. This was omitted from all later versions of the game. Seeing room for improvements, Chahi would oversee the port of Another World onto Macintosh and DOS, while letting the port coding duties go to Alan Pavlish and Bill Dugan for the Mac version and Daniel Morais porting Pavlish’s work over to DOS. These home computer versions differ significantly in some areas. New sections were added to certain levels, more hazards in the maze air ducts and better enemy placements along with more checkpoints. Between them, the Macintosh version has higher quality graphics than its DOS counterpart.

All these initial ports were overseen by Chahi to ensure no unneeded changes were made to his art. However, when preparing for launch in the US market, Delphine signed the publishing rights to Interplay, an American publisher who at the time had published other science fiction works like Neuromancer and the Star Trek games. It was through the collaboration with Heineman that this deal was struck, and while it enabled Another World to see a much deserved worldwide release, it would be a deal that would prove near catastrophic for Another World and Eric Chahi.

Interplay came early in the relationship with a list of demanded changes for the game to “work” for an American audience, and to extend the value for the console gamers. Among the demanded changes were a more elaborate ending, harder difficulty and most severely, a complete replacement of the sound and music by Freitas. Chahi, who had always been a lonesome worker and very protective of his creations, was infuriated with the demands and would send faxes daily vetoing every change that Interplay saw required. The communication became so tense that eventually, Chahi devised a plan where he would put “KEEP THE ORIGINAL MUSIC” on 2 sheets of paper, tape the ends together and create a circle fax that would loop infinitely until there was no more paper in the fax machines at Interplay HQ. When informing Delpine’s lawyer, Anne-Marie Joassim, of his fax terrorism plans, she insisted that she would first call Interplay to clear up the situation. The results of her phone call, the original music was to be kept, but new music be added during the levels. Chahi agreed, and Charles Deenen composed a cinematic score to go along with the action.

In 1992, the game was released on the SNES and Sega Genesis through Interplay. These versions would become the platforms where Another World would achieve its greatest success and acknowledgement, and while both versions are great games and easier to access than the computer versions, neither version should be considered ideal. The Genesis suffers the most setbacks out of the two with a limited color scheme with fewer and brighter colors, which dulls out the blue melancholy tint. The sounds are also of lower quality. The SNES version looks fantastic and has a wonderful sound but trouble arose yet again when going through the approval process which Nintendo enforced. All traces of blood and nudity had to be removed for it to be released and Chahi had no choice but to apply the changes. The nudity in question is a visible cleft on the rear end of the aliens in the bath house near the end of the game. The console versions got a new level. To lengthen the game, a citadel/training camp level was added before the coliseum fight. It is one of the longest stages and adds a lot of content into the game, as Lester must help out his alien friend who is stuck hanging from a curtain after a failed attempt at bouncing up from it. Also new to the game is the inclusion of a prologue text which tells an entry into Lester’s diary. The content of this prologue differs slightly between the versions. The SNES version was ported to Apple IIGS, and this was apparently the only time a SNES was ported directly onto the computer system despite sharing the same W65C816S processor. All these ports were handled by Heineman.

Years would pass and with the legacy of Another World having come to a peak, Chahi had moved onto new ideas and games. With his new founded company, Amazing Studio, development was well underway on Heart of Darkness. It was because of this fact that Interplay now could bypass Chahi’s tight grip and make the changes they saw needed in order to make Another World fully realized per their opinion. In 1993 the 3DO port would perfectly illustrate not only the mistake in their beliefs, but also disrespect to the original intentions of the work of art Chahi had worked two hard years on. On paper this version might sound great, all new hand painted backgrounds, all new soundtrack by Andrew Dimitroff who had a prolific career as a music supervisor for DIC animation and last but not least, an extended ending. While the backgrounds are of mostly high quality, they serve as a great distraction to the game, with the original polygon characters looking out of place and stale because the pieces do not complement each other. The blue tint and density is completely gone, and the backdrops simply gives too much visual information to the player, eliminating a lot of the mystique that originally made the game so different, and without any animation, the world feels slow and static. The soundtrack is a miscast beast in itself, with a bombastic sci-fi sound that constantly keeps itself in the foreground of the action instead of back dropping it. While in itself a rather interesting and experimental soundtrack, it is something that would fit an episode of Bravestarr more than Another World.

But maybe worst of all is the ending. After flying into the horizon as we previously have seen, the credits will start rolling and everything seems normal and to have come to an end. This all changes when you suddenly see your alien friend landing with Lester in his arms unconscious, and having flashbacks of what happened to his once peaceful village. The scenes we are seeing here are actually the intro that what would become Heart of the Alien, a sequel produced by Interplay and released one year later. While using the ending to promote the new game, it wouldn’t actually be released on the 3DO but rather on Sega CD. Chahi has expressed deep regret over not having paid more attention to what Interplay was doing to the 3DO version of his work.

The original Another World would be included on the Sega CD sequel. This version is probably one the best of the console ports. Though similar to its Genesis sibling, it features another new soundtrack, though this time by Freitas returning to score the game with direct influence from Chahi. It sounds great and in comparison to the 3DO soundtrack is leaps and bounds more fitting to the soul and spirit of the game. This would be the last commercial port until 2007.

Several homebrew ports have been developed during the 2000’s. In 2004, Cyril “Foxy” Corgordan reverse engineered the Atari ST version, which allowed the game to be ported to other consoles, in this case, the Game Boy Advance. Initially Chahi put a halt to the distribution of these files fearing loss in potential business, but would later embrace the port and allow the game to be released as freeware. Due to this, the game was also ported to Dreamcast, GP32 and it would be the groundwork for the Symbian phone port. The GBA and phone ports are all made brighter to make up for the smaller screen and less details.

In 2006, the game celebrated its 15th anniversary and Chahi saw a chance to go back and release what he would personally dub the ultimate edition of the game. Released for play on Windows, this version supports HD resolution, has all new backgrounds drawn by Chahi, a completely reworked and re-recorded soundtrack and sound effects by Freitas and comes with plenty of extras. On the disc you will find the soundtrack, the tech diary Chahi kept during the development of the original game with all the code and physics that went into the game, a design diary with concept art and character designs and a 20 minute making of documentary. The package is magnificent, and provides incredible value and collectors’ items for your money, but when initially released, it had a severe problem. The initial batch of CD-ROMs came with a DRM that would only allow 5 installs from the disc and once that number was reached, the disc would render itself useless as it could not apply its serial anymore. This forced you to buy another copy if you wanted to install it yet again. It was eventually removed altogether. The 15th Anniversary version can be downloaded DRM-free at Good Old Games.

Links:

Another World.fr Eric Chahi’s personal Another World website with development notes, art and other trivia.

Heart of the Alien Redux Gil Megidish’s SDL engine for the sequel.

Screenshot Comparisons

Versions

Intro