Most retro game fans will have heard of Assault Suits Valken on the SNES, known as Cybernator in the West. A fantastic and deservedly loved action title where you roamed maze-like levels blowing up other robots, with an impressive sense of scale, some explosive set-pieces and a decent storyline. It was actually preceded by the lesser known Assault Suits Leynos (Target Earth in the West), and unsurprisingly it also spawned several follow-ups and imitations, such as Metal Warriors and Front Mission: Gun Hazard.

Aquales could easily be mistaken for just such an imitator, except that it was released in 1991, after Leynos but prior to Valken. Along with its similarity to the Assault Suits series it also has resemblances to other games – for one thing, certain weapons almost feel like something out of Ranger X, and one music track in particular sounds like it’s lifted straight out of Ecco the Dolphin. Of course Aquales predates all of these. The only obvious game known to the West which it does draw inspiration from would be Bionic Commando, since Aquales features the same rigid grappling mechanics (those expecting the realistic, stretchy physics of Umihara Kawase should look elsewhere).

Aquales is a forgotten evolutionary ancestor. Likely influenced by obscure titles such as Zoom’s 1989 mecha-actioner Genocide – except instead of Genocide‘s slow ambling bipeds and insipid combat, developers Exact pumped things up to create something special – but only released within Japan’s home computer bubble. It never made the jump to popular consoles the way Genocide 2 did and, while it possibly influenced later Japanese developers, Aquales remained unknown in the West.

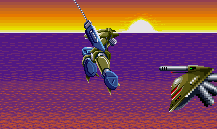

Nothing in Aqaules should appear new or ground-breaking; despite only existing on an archaic Japanese home computer it contains elements found in dozens of later, far more common titles. What makes it special is the panache with which it pulls things off – everything about it oozes the kind of 16-bit energy you’d expect from a Mega Drive Treasure title. It may not be as refined as a Treasure game, since the enemy AI is a little too scripted and the action is never quite as spectacular as something like Alien Soldier, but Aquales tries very hard to make you like it. Almost every sprite-based game lazily mirrors the left and right sprites to create ambidextrous characters. Not Aquales, where you only ever shoot with the right arm and grapple with the left! Colourful anime cinemas explain the backstory. Despite originating in Japan, all the intro text is conveniently in English.

The music throughout is nothing short of incredible, containing a blend of hard-rocking heavy metal, with some outstanding guitar riffs, mixed in with more ambient and eerie tunes for the underwater ruins. Gameplay, while not overly varied, is solid and compelling. There are 12 weapons to find over 8 lengthy stages, each of which pulsates with the kind of detailed parallax scrolling (8+ layers), enormous sprites and special effects which we’ve not seen since Thunder Force IV. It’s difficult to capture this splendor in screenshots – only in motion can you appreciate it.

Along with the expected swords, chainguns and rockets, there are also bouncy bullet weapons, blades on retractable chains and, the coolest, gravity flame throwers where the fire clings to and races along whatever surface it touches. The most significant item though is your grappling hook, capable of latching on to any surface and carrying you safely across hazards. Required throughout, as commonly as jumping or attacking, it keeps the game’s tempo interesting, There’s a myriad of other small touches too, such as gaining experience points for defeating enemies. Rather than artificially lengthening the game this instead allows for semi-random power-up moments. Grinding is never needed, but it rewards thorough playing.

It would be easy to nitpick at Aquales various faults, such as the difficulty, which sometimes wildly fluctuates between too difficult and too easy, or the at times clunky controls endemic of computer games, but for a game released in 1991 its ambitious nature – faults and all – is admirable. It is at once wholly familiar, and yet also exotic and captivating because it’s on such a relatively obscure platform