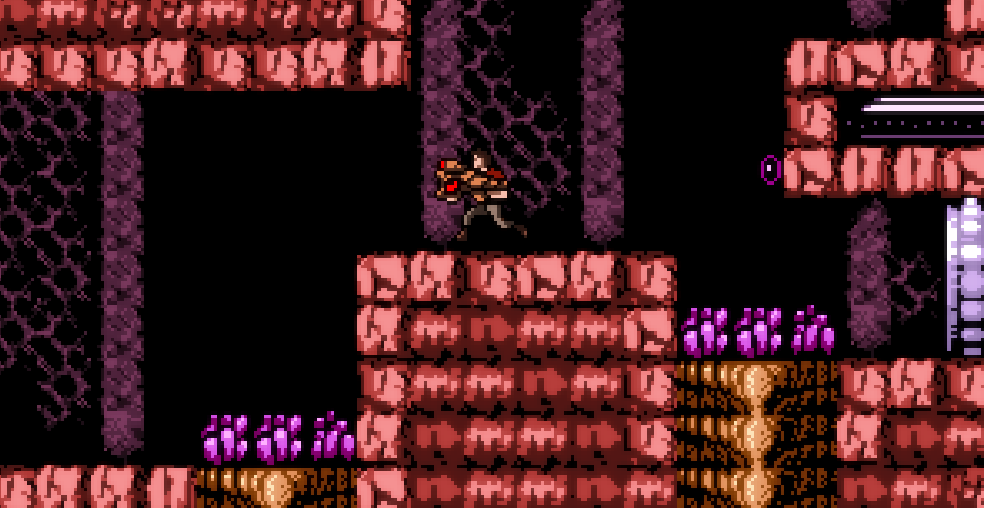

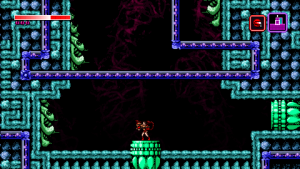

Metroid (together with Castlevania: Symphony of the Night and its successors) are the two names that created the “Metroidvania” subgenre, a style of game that has many indie developers are particularly fond of. Yet in spite of many of the games that utilize this game structure, none really fashioned themselves that closely after the original Metroid. Tom Happ’s Axiom Verge, however, wears its inspiration on its shoulder, with a visual style that directly homages many areas of the 1986 8-bit games, even including similar looking doors (though without the famous bubbles). At first glance, it does seem to tread a little too closely to this style. But, instead of a game that just imitates the graphics of Metroid or other NES games like Blaster Master, however, Axiom Verge is a game that understands them and also captures their sense of mystery.

When the game begins, the introduction sets an expectation for something typical. Our hero, a scientist named Trace, is transported to an alien world while performing an experiment. He is then saved by a benevolent being named Elsenova, that needs him to save her and what is seemingly her world. But despite the deceptively average setup, things quickly go in a very different direction, with Trace being thrown into the thick of a wrecked planet that holds several insights about both its massive overseers as well as Trace himself.

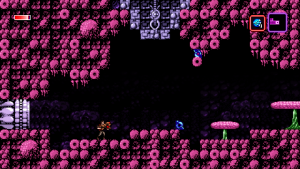

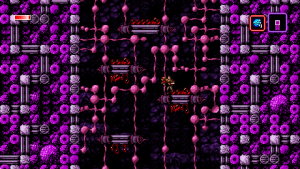

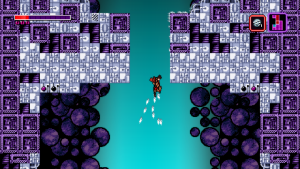

That’s not to say Axiom Verge accomplishes this at the expense of its graphics. They’re actually excellent, being colorful, varied, and immediately working with each area’s music to let you know the general tone of the confrontations you’re in store for. In fact, in contrast to the visuals, the music sounds closer to a Jeremy Schmidt album than a typical retro-style game soundtrack, and it’s all the better for it.

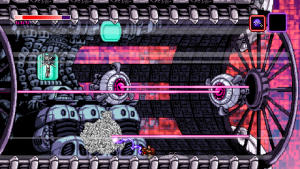

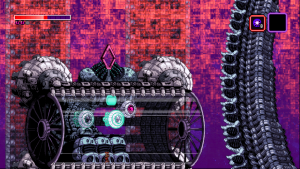

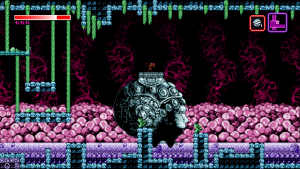

An especially inspired touch is that the dimensional pandemonium rampant throughout the game’s world is represented by the scrambling of enemy sprites and garbling of background tiles. Indeed, some of the “keys” to get around the game’s structural “locks” play with this, like allowing you to ungarble these areas to proceed. Nearly all enemies can be glitched, making them behave differently. Sometimes these just neuter their damage or otherwise let you use their altered forms to proceed, much in the same way that the Ice Beam in Metroid let you climb on frozen creatures to new heights. It’s incredible in practice, both making it immediately clear what items and abilities are needed to pass an area while at the same time tapping into nostalgia for the graphical glitches that would appear often in NES games as players pushed them to their limits. This concept is evident throughout the game, where each aspect of its design works both as a way to make this type of game accessible to new players while also showing great aesthetic insight for fans of the classics. There’s even an in-game password system, where you can input certain passwords in specific areas to unlock them and find new stuff (and there’s some specific homages to Metroid‘s swimsuit outfits here too). Plus, there are several glitched worlds, whose appearances are displayed as it through a static CRT, whose locations are randomly determined at the start each game. Owing to the “secret world” bugs of some NES games, it gives more of the impression that there’s some unknowable area sitting just outside of the boundaries of the game’s code, waiting to be explored.

The focused presentation achieved here is rare. The same way Dust: An Elysian Tail‘s design makes it look like a game that would have been made on a hypothetical “Sega Saturn 2”, so with Axiom Verge, Happ masters a similar visual balance. The game’s content is obviously beyond the scope of the NES, with several extra effects and an impressive variety of areas to explore. At the same time, he presents an amalgamation of modern world building in games with the use of color and enemy design needed to be immediately evocative of NES titles from Sunsoft, Capcom, and others. It’s very refreshing to see a game developed with such a passion for these older titles not succumb to more dated aspects of their design out of a misplaced sense of authenticity or trying to attain the non-goal of being a “real” video game. Happ understands that the raw appeal of adventure games like Blaster Master and Metroid comes not just from an obtuse level complexity or dark graphics, but from balancing these elements together to create an air of mystery that begs us to explore the game as deeply as possible.

What becomes clear the more you play, however, is that the way you control Trace is not just an imitation of a single NES game, but rather a combination of ideas found in a variety of them. When Trace gets a grappling hook, as an example, it would have been easy to have it function the way a similar item does in Super Metroid in keeping with the game’s primary inspiration. However, it’s instead based on the excellent grappling controls found in Bionic Commando. This allows for some intricate platforming action while still making the item intuitive to use compared to Super Metroid‘s looser swinging action. It’s a pleasure to find new ways of traversing the world of Axiom Verge, as each ability drastically changes the way players will approach each section of the game. Other weapons recall other games, particularly a gun that’s a lot like the Diskarmor from Rygar. You also get many of these items early on, letting new players quickly get used to poking around for secrets and experimenting to reach new plateaus. And indeed, many weapons are actually completely optional, giving the player lots of extra stuff to hunt for.

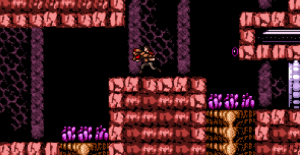

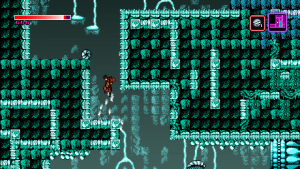

A huge part of the appeal of these types of games is not just that the player can get lost, but that their worlds are designed around the idea of breaking them. One crashes through boundaries constantly to uncover new areas. To put things in perspective, when Metroid was first released, it was one of the earliest console games where the screen could scroll both vertically and horizontally. This combined with having to blast through walls and find secret passages made for an incredibly labyrinthine and challenging experience when combined with its Alien-inspired sparse atmosphere. Not many developers attempt to duplicate this type of exploration where it’s less about passing by the scenery and more about laterally traversing through it, but Axiom Verge pulls it off. More importantly, it pulls it off in a unique way, with abilities that will let the player teleport through walls and perform other tasks that are evocative of exploiting glitches in the classics, but functioning here as refreshing ways to get around the idea of hunting a world just for keys or a way to jump higher. So again the game’s structure is able to both look and feel fresh despite the constant homage to older games.

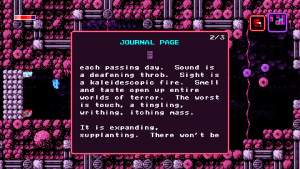

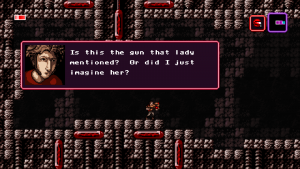

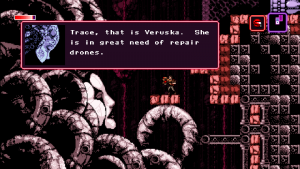

Axiom Verge definitively nails the sensation of falling into the unknown. A big part of this is in the quality of life improvements here compared to 8-bit titles. Aspects of the game are made more convenient, but not too convenient. There’s a map that shows the Trace’s location, but not his objectives. There are numerous places to save our progress in, but no way of quickly traveling from one end of the game world to the other. There’s a character in the game that tells us about the setting but her explanations are often fragmented and teasing. Otherwise, much of the backstory is relegated to finding notes and records scattered throughout the game world.

Enemies are a bit more durable than in most 2D action games but the controls let you aim your weapons much more effectively. It’s a perfect balance, giving us an experience that is accessible and modern while still focused on delivering the sense of travelling through the completely alien, barren existence. It’s also quite a bit more difficult, because while there are ways to expand your life meter, they’re never as expansive as the many Energy Tanks you could find in a Metroid game. Thankfully, upon death, you’re simply transported back to the last save point you reached with no other penalty.

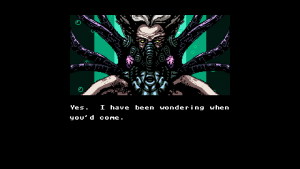

From a storytelling perspective, while Trace may seem bland at times, the script’s pacing is excellent. Happ creates an intelligent merger of level design and story, with Trace coming to the aid of a barely functional artificial intelligence that gradually dispenses more and more information to him. While this slowly increasing ebb of knowledge from your taskmaster is a hackneyed prelude to betrayal and plot twists in most adventure games, here it is both plausible and appropriate. As the game goes on, Elsenova’s condition improves along with her ability to speak English, so her blunt explanations and sudden silences never feel out of place thanks to her form initially being as decayed as the world she inhabits.

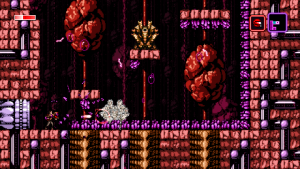

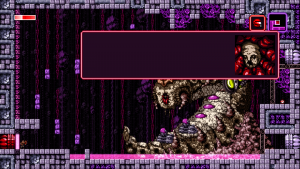

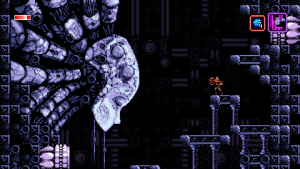

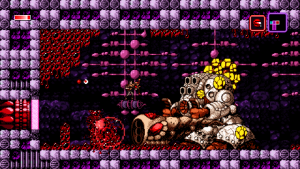

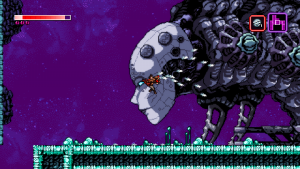

If there is a flaw in the execution of Axiom Verge‘s story, it lies in an inconsistency with Trace himself. There’s a bit of a disconnection where the character carries himself with levity and cynicism, almost above the bizarre situations he finds himself in. He is then suddenly confused and regretful during dialogues with the game’s early bosses. This is a bit jarring, and is a disservice to the game’s outstanding art direction. Trace has no problem blowing away dangerous local fauna and bending the fabric of reality, all the while pointing out how he does what he does only to defend himself. But suddenly it’s these massive biomechanical behemoths which exist only to destroy him that give him pause for thought. You start to see why this is reasonable as the story progresses, but one can’t help but think that Happ inadvertently had Trace’s personality informed by information the character has yet to learn. It’s difficult to balance the suspense gained from having a character know too little or too much compared to the audience, but in this case the early boss encounters feel at odds with the rest of the script. When the bosses look and behave the way they do – as gigantic, terrifying monsters – having no pre-fight dialogue for the early ones may have been ideal when some body language as well as the massive form of the bosses themselves would do.

Any areas surrounding Elsenova and the game’s other AI are great examples of this visual storytelling and implication. Too few games attempt to do this so ambitiously, where there are cues of terrible things that have happened without being given the full picture for some time (or possibly never depending on how aggressively the player seeks out hidden memos and notes). According to an interview with Hidetaka Miyazaki via The Guardian, when he became the director for Demon’s Souls (and later two of its spiritual successors), his growing up in a poor household was a major inspiration for how the story is delivered in those games. Without access to the comics, movies and toys other kids had, he’d spent a lot time in the library devouring stories he often couldn’t fully grasp due to his age.

This opaque narrative is integral to that series, and it’s great to see a similar delivery in Axiom Verge. It taps into a very primal aspect of how our fears and hesitations function, hitting us not because we are unaware of what’s going on, but because we are acutely aware of certain details while lacking the knowledge and experience in the world around us to fill in the gaps. For this reason Axiom Verge‘s pacing leaves one insatiable, with fragments of the game’s plot being just as rewarding as finding a new weapon. This is also helped by the player being introduced to Elsenova very early in the game. Players run into what is effectively a towering goddess of exposition early on that is incapable of immediately giving us answers. Even the ending (which, as is tradition, changes due to various completionist factors invisible to the player) is ambiguous, meant to inspire conversations with other enthusiasts.

It’s also an ideal way to make use of the visual design found in those NES games where getting lost is part of the experience, so Axiom Verge offers the best of both worlds. It’s a loving tribute to the pharaonic iconography of the Metroid series, the sprawling wilderness of Shadow of the Beast, and the labyrinthine ruins of Legacy of the Wizard. At the same time, Happ uses all of these to great effect, providing a foreboding and rewarding experience that can resonate with both fans of these classic games as well as new players. Metroid has had plenty of imitators that function like it only on the most superficial level, failing to capture the sense of exploration and truly alien culture featured in that series.