Chris Roberts has become a name synonymous with the term “video game designer.” Like Richard Garriott with Ultima and Shigesato Itoi with Mother/EarthBound, Roberts’ claim to fame has come primarily through a single series, namely Wing Commander. Roberts designed, directed and produced the initial title and remained involved throughout the series’ run, even directing the theatrical feature film based on the game.

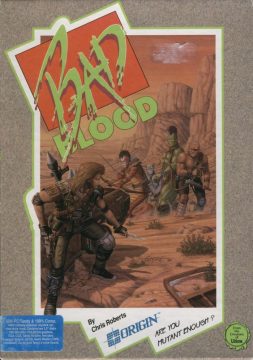

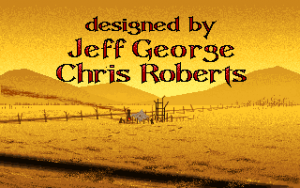

But Roberts didn’t start his career there. After programming a few games for the British computer BBC Micro, he joined Origin and released Times of Lore, a game he directed, designed and co-wrote. Although critically acclaimed, Times of Lore was not hugely successful. Jeff George, another Origin employee who got his start by writing the manual to games like Knights of Legend, came up with a post-apocalyptic Mad Max-esque setting far removed from the “swords and sorcery” type games that Origin had become known. Working together with Roberts, Bad Blood was born.

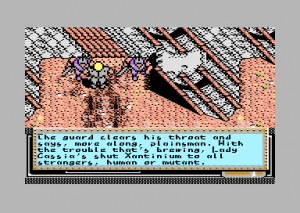

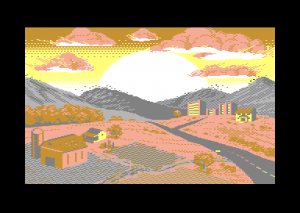

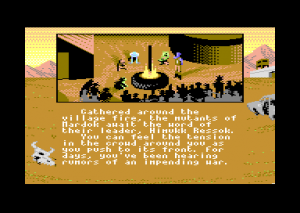

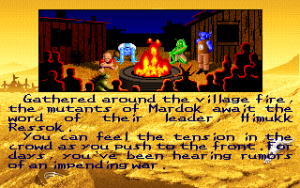

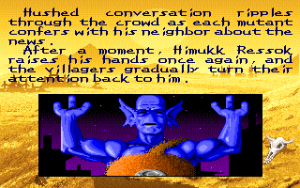

In the near future, an atomic bomb is launched, rendering much of civilization a barren wasteland. Some of those who survived began to feel the effects of mutation and radioactivity and were cast out by those who lived with their humanity intact. As time passed, society has split into two major factions: the humans (or “humes” as they are referred to in-game) and the mutants (“mutes”). Bad Blood begins with the rumor that the humans are threatening all-out war against the mutants to finally eradicate their kind. The mutants, who are under-powered and lack the force necessary to withstand a human attack, wish to sidestep any potential conflict and seek peaceful resolution instead.

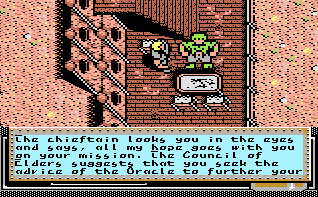

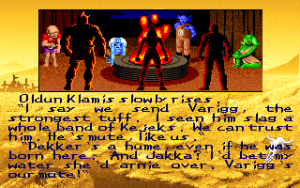

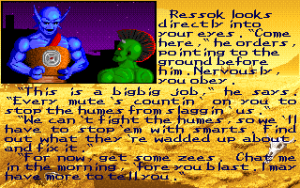

For one of three different “tuffs”, it is their job to see if there is any truth to the rumours, and if so, attempt to negotiate with the humans. The characters can be chosen include Varigg, a full mutant with super strength but noticeably green skin; Jakka, a female who looks human in appearance but has mutated with the ability to shoot lasers out of her eyes, or Dekker, a full-blooded human who is sympathetic to the mutant cause. The game gives both pros and cons for choosing who should undertake this mission, but ultimately, it is up to the player to decide.

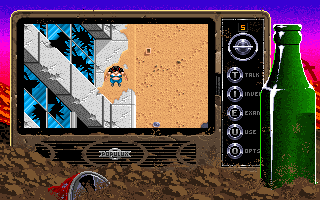

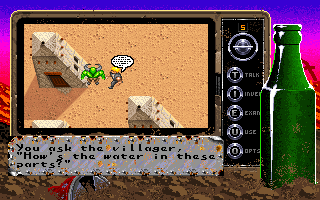

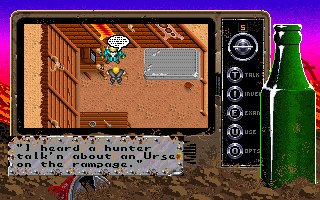

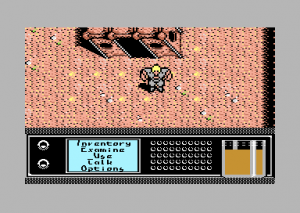

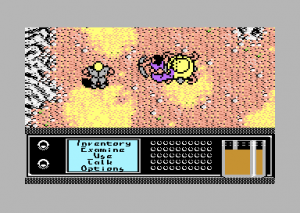

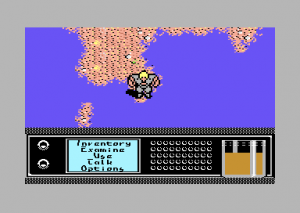

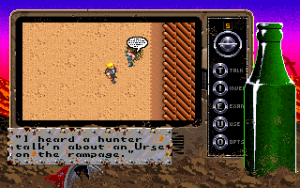

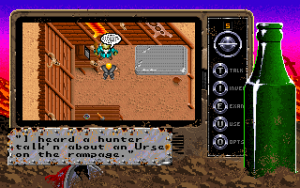

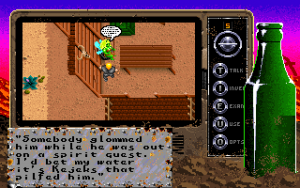

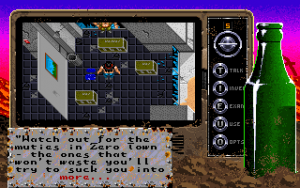

Once the character is chosen, the game shifts to a top-down view on a television screen where the action for the rest of the game will take place. The thing that is immediately noticeable is that the actual playfield screen is…small. Approximately 55% of the screen is decorative border The buttons on the actual TV serve as reminders for each function the character can perform (and can be cycled through and selected if using a joystick). The large bottle on the right hand side actually serves as the character’s health bar. The liquid inside will drop as the player gets hit or injured and the player will die once it is completely empty. The skyline around the top of the television changes through the day/night cycle from morning to evening to nighttime and back again as the player progresses through the game. Speech boxes and choices appear below the television. Although these extra trappings are not particularly useless, redesigning the main screen to have a bigger playing field would have helped the view seem not as cramped.

Unlike Brian Fargo’s Wasteland, released two years prior to Bad Blood, there is no party or turn-based combat. Instead, the character travels solo; enemies are fought in real time and are visible on the screen. Much like other RPGs of the era, however, very little hand holding occurs. The first task given to the player is to go find the Oracle, but who or where the Oracle can be found is up to the player to find. Fortunately, there is a rough map inside the manual but most of the world is up for exploration. If things get too out of hand, the player can switch from the default “Warrior Mode” to “Wimp Mode.” In Wimp Mode, there are fewer monsters to battle and time will stop whenever the menu is used rather than progressing no matter what.

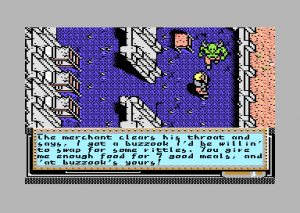

Combat is a simple affair. Even in Warrior Mode, enemies can be dispatched with a few hits from the standard weapon, not to mention the bow and arrow or “nades” (grenades) that the player can use. There is one enemy that routinely drops an item that can replenish the player’s health as well. Most other enemies will drop food, which is needed so that the player doesn’t starve, but doesn’t replenish any health. After dispatching only four or five enemies, there will be enough food to last for a couple of in-game days. Figure in the countless hordes that inhabit the wasteland, and there will be enough food to last a lifetime. Unfortunately, with combat being a simple affair, the player can actually choose to avoid most battles. Coupled with a knowledge of the world’s cities and villages and where major plot points occur, the game can be easily beaten within a couple of hours.

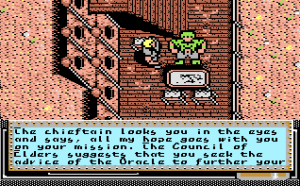

Not only does Bad Blood owe a debt to Mad Max in terms of setting and plot, but also in the dialogue and language that is spoken between the characters. The manual has a glossary printed inside of it so that players can decipher what exactly is being said, although it’s not that hard to decipher. Consider this opening exchange from the first NPC when the player asks him about the Oracle: ”Buzz is, the Oracle’s oldest, shivviest mute on the Plains. Some say he saw the Great Fires. If he’s still kick’n, he’s turkelled up somewhere like a hermit.” It almost feels like everyone should be speaking with an Australian accent.

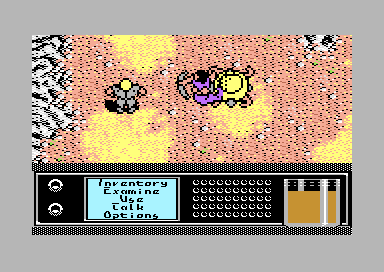

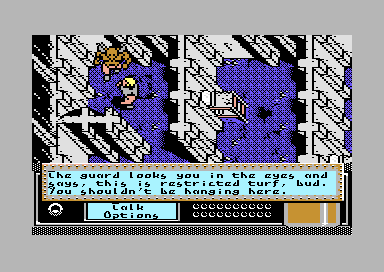

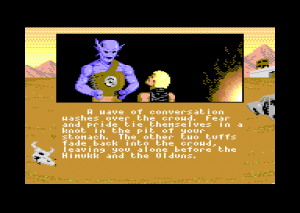

Unlike Roberts’ previous game, Times of Lore, Bad Blood only received one port from the original DOS game and that was for the Commodore 64. This version keeps the intro and the basic gameplay intact but has a few differences than the DOS version. The main difference is that the action screen is more streamlined. Gone are the TV screens and water bottles, replaced with a simple taskbar and a mug to ascertain the character’s health. The player and enemy characters are visually more pronounced, making use of the extra space of the playfield. Despite the lack of colors as compared to the DOS version, the visuals almost seem more vibrant at times. A curious decision was made regarding the speech of the characters. All of the “flavor” and slang has been stripped away and replaced with standard English. The effect is especially jarring coming right after the intro, which is identical to the DOS version. Why such a change was made is not immediately known, but it takes one of the unique features of the game and completely removes it.

There has also been mention of a re-release of the game in 1994 that adds 256-color VGA graphics. However, the original version already supports VGA, and both the marketing materials and the gaming press in 1990 after the initial release make mention of it. There doesn’t seem to be much more information about it beyond a brief description, and is devoid of any other media surrounding that particular release. It’s possible that the game was still re-released in 1994, but changed nothing beyond a few bug fixes.

Overall, Bad Blood presents an interesting entry into the Origin gameography. As an action game masquerading as a RPG, no one would ever mistake it for being an early Ultima title. And yet, for a company renown for its RPGs, it puts its own spin on the style before the next big franchise, Wing Commander, would move away from the genre as a whole. Although those new to RPGs and classic computer gaming probably won’t find much to be excited about here, those who have been looking for something different than the usual medieval settings or those who have been enamored with the recent rise in post-apocalyptic games should give Bad Blood a try.

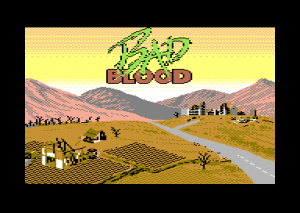

Screenshot Comparisons