- Banner Saga, The

- Banner Saga 2, The

The Kickstarter crowdfunding platform has changed the gaming industry landscape quite a bit in recent years by reintroducing smaller, software house-style game development studios that seemed to have been largely disappeared in the early 2000s. On a good day, those companies produce games that fall somewhere between the higher production values of their big-budget peers, the creative freedom and niche focus of the indie scene, using the experience of industry veterans to their full extent – think Wasteland 2 and Shadowrun Returns. On a bad day, they give us high hopes for the products that never get finished or just end up sucking.

The Banner Saga was one of the first big crowdfunded game projects and fortunately it belongs to the former category. The result, created by a trio of ex-Bioware employees (known mostly of their work on Star Wars: The Old Republic), might not be a flawless game, but it definitely deserves attention – the important things are done well as it has an interesting premise, solid gameplay and a beautiful art style.

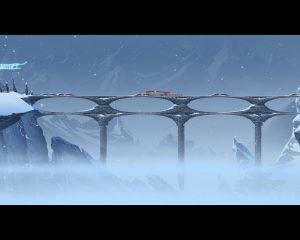

The first thing to note about this game is how great it looks. The Banner Saga features beautifully painted backgrounds (with a detailed landscape and surprisingly diverse cities and villages) and amazing character artwork reminiscent of an old Disney film (the look was achieved by rotoscoping – tracing over live-action footage – such as in Jordan Mechner’s games like Prince of Persia and The Last Express). The visual style of the game is also noticeably influenced by Viking art – very fitting for a game inspired by Norse mythology.

Amazingly, The Banner Saga manages to keep its look consistent throughout the entire game. Sure, the sprites used during battles are not as big and detailed as the characters in dialog screens or cutscenes but the style is the same, the animation is very fluid and you can clearly identify each individual character (well, at least the playable ones; enemies use the same sprite for every enemy of the same class). Banner Saga wants to look like an animated movie and it manages to do so as much as the formula of a turn-based tactical RPG allows.

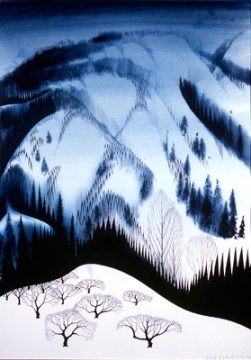

The post-game credits cite Eyvind Earle as the main inspiration for The Banner Saga’s art. Earle was a painter known for his work as a background illustrator for some of the classic Disney films, most famously Sleeping Beauty. His non-Disney work consisted mostly of natural landscape paintings, although he also produced sculptures and portrait sketches.

The world of The Banner Saga is not a happy place. In a surprisingly depressing twist on the idea of a Viking legend, the gods (not the familiar ones from the Norse mythology, as the setting is an original world, only inspired by the myths) have already died – and it didn’t happen in a giant, world-ending battle. But the world still seems to be ending, just in a different way – the sun has stopped moving, the cities are being attacked by stone people called dredge and somewhere deep in the mountains a mysterious Serpent laments that soon there will be no more world for him to devour.

There’s been a lot said about the non-linear nature of The Banner Saga‘s story and the importance of player decisions. The game delivers on it only partially, similar to most of the games made by Telltale: there are events that can be influenced by your choice (often related to different characters being recruited or dying) but the major plot points can’t be changed (for example there’s no way to avoid destroying a certain bridge). The characters who might die because of your decisions are also mostly the less important ones, although there is one notable exception near the end of the game that’s supposed to carry over to the sequels, so at least there’s hope for more non-linearity in the future.

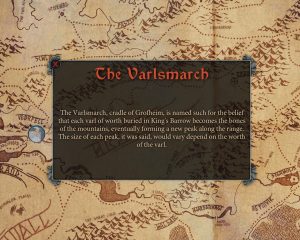

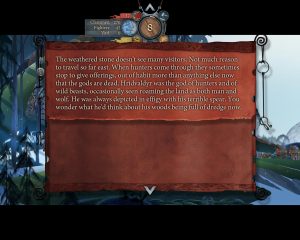

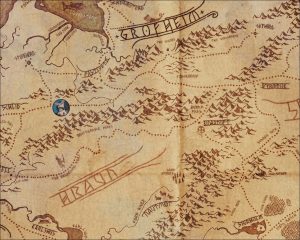

The principal characters in the game are humans and horned giants known as varl. They travel through the world, fight against the dredge and try to survive in the unfriendly environment. The game’s story is revealed slowly through dialog, narration and, to an extent, the world’s landscape where the once great cities have turned to ruin and the godstones (monoliths inspired by real-life menhirs and runestones) either abandoned or surrounded by people desperately praying to the dead gods. The background slowly changes as you travel through what is possibly the best video game representation of what a long journey actually feels like. Patient players can find out more about the land from an in-game map, which contains a description of every region, city, island and mountain range.

Characters

Ubin

The main character in the early game and the only POV character that is not playable in combat. Ubin is a tax collector and a scrivener who avoids fighting as a part of a strange competition: to be the oldest varl alive. He leads the expedition to rid the surroundings of the city of Strand from bandits.

Hakon

Hakon is a legendary warrior who travels with the caravan led by Vognir, heir to the varl throne tasked with stopping the invasion of dredge from the north. He becomes the leader after Vognir dies in the battle early on.

Rook

A hunter from the village of Skogr who notices the arrival of dredge forces. He escapes with the rest of the village and – just like Hakon – soon enough becomes the leader of the caravan after the current chieftain is killed in the battle. He is the central player character for most of the game.

Alette

Rook’s daughter and a very skilled archer with a unique ability of shooting multiple enemies in a turn as long as they stay in a line. She’s a potentially powerful fighter but a reluctant one, as she initially dislikes fighting against humans and varls.

Oddleif

A wife of the late chieftain of Skogr, she was a de facto leader of the village before her husband’s death. Oddleif is an archer who wishes to teach women in the caravan how to fight with bow and arrows. She seems to develop romantic feelings for Rook during the course of the game.

Iver

The only varl (at least at first) in Rook’s caravan. Iver seems to prefer humans to varls – but there’s a reason behind it, as he has a past as a warrior that he isn’t very proud of.

Eyvind

A mender (the equivalent of a wizard in the world of Banner Saga) found by Hakon’s caravan in a ruined fortress. He temporarily saves the varl city of Einarfort from a stonesinger (a dredge wizard). His name is a reference to Eyvind Earle.

Juno

Eyvind’s mentor and romantic interest, Juno is a member of the mysterious mender council. She’s presumed dead by the Hakon’s caravan but returns some time later and devises the plan to defeat the game’s final boss.

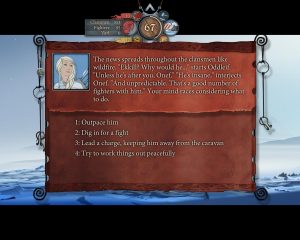

The gameplay of The Banner Saga is based on three core elements: picking decisions in style of choose your own adventure games, resource management and tactical combat. The first two – combined with mythology-inspired setting – might make the game sound a bit like King of Dragon Pass, although there is a major difference between the two: while King of Dragon Pass uses random semi-random events triggered by exploration, relations with neighbors and owned resources, everything in The Banner Saga is scripted, with some difference based on your previous decisions.

The resource management aspect of the game is quite simple. First thing you need to care about is your supplies, as a lack of them causes warriors and villagers to die and morale to drop. Supplies are used along the way as your caravan travels to another destination, Oregon Trail style, and the biggest strategic choice related to them is between resting after combat so that your characters are at full power and rushing to the next town so that you won’t starve. The second resource is renown, which you gain by winning the battles and use in order to upgrade your characters and to buy items and resources. The third is the size of your caravan – larger ones have an easier time in large-scale battles while smaller ones consume less supplies. Generally speaking, you won’t need to worry about any of those things while playing as Ubin or Hakon, but you will be forced to make some tough choices in Rook’s chapters.

During the tactical portions of the game, you’ll need to pick individual characters to participate in fights, decide the order in which they attack and position them on the map. Player and enemies will take turns, moving on a grid-based map and attacking their opponents. The attacks can target the enemy’s strength (which determines both hit points and damage caused by attacks) or defense (which determines the possibility of deflecting attacks completely and reduces their damage otherwise). There’s also a willpower stat (partially determined by caravan’s morale) which allows the characters to use special skills or simply move further and hit stronger during their turns. It’s an interesting system, although it gets reptetive after a while due to the limited number of enemy types.

Characters level up by killing enemies (and spending renown), which allows you to allocate points to different stats. The stats can also be increased by wearing special items bought or found during the game (keep in mind that stronger items are restricted to high-level characters). Interestingly, a character who is defeated in a fight isn’t removed from the game – that can only happen through events – and is given a ‘wounded’ status instead, which causes their stats to drop until they rest for a certain amount of time. In fact, losing a battle doesn’t always end the game as the caravan often rescues the defeated fighters. There are always consequences though, and a string of failures might lead to a long, drawn-out death as underlevelled characters lose one fight after another, until they run out of supplies and starve.

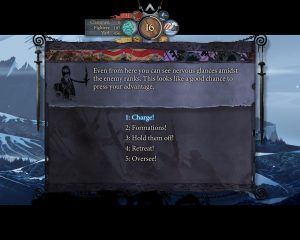

Occasionally, the caravan will meet a large group of enemies. In that case, you’ll have to pick a strategy that your army will use. Most of these lead to your characters taking on some of the enemies in a tactical battle, and the one that doesn’t is not worth using. The results of the large battle depend on the chosen strategy, the outcome of the tactical battle and the number of fighters on each side. The biggest difference between this and the usual combat is that a failed battle results in the deaths of your caravan members and has a bigger effect on morale.

The Banner Saga features a beautiful soundtrack by Austin Winthory. The music has an obvious folk inspiration and is appropriately suspenseful and melancholic, fitting the game’s atmosphere perfectly. The linear and scripted nature compared to the aforementioned King of Dragon Pass, for example, allows the tracks to be associated with certain scenes and characters, which really helps create emotional impact.

The soundtrack’s highlights are definitely the vocal tracks that play when you pass a godstone. Singing isn’t usually expected from video game music (with an exception of intros, final bosses and ending credtis) so hearing it might be a bit of a shock the first time it happens. The sorrowful singing combined with the general atmosphere of The Banner Saga‘s music greatly amplifies the sadness of abandoned places of worship as it genuinely feels like your caravan is mourning the dead gods.

The sound effects are generally very well done. As can be expected, they are mostly battle cries, screams and sounds of weapons – and there’s nothing to complain about here, especially given that each named character is voiced individually. There is not much voice acting outside of combat though – the POV character will occasionally do some narration as the caravan enters an important place, but everything else is told through non-voiced text.

The Banner Saga was first released for Macintosh and Windows PCs, an identical version was then ported to iOS and Android. In fact, it feels like the game was designed with touchscreen devices from the beginning, as nothing except skipping cutscenes or dialog in the game requires the keyboard or the right mouse button. That is not to say that there’s something wrong with the interface design – it’s intuitive without being dumbed down. The only complaint is that skipping cutscenes always jumps to the end or to a player decision, without an option to advance to the next line. There is a PlayStation 4 and PS Vita port underway and how the game is handled with a controller remains to be seen.

The Banner Saga is a great, well-thought out game with a unique atmosphere. However, it is simply too short and ends just when the plot is getting more interesting and the player choices become more important.

Links:

Stoic Studio The official website of The Banner Saga developers

The Banner Saga soundtrack on Bandcamp

The Banner Saga Wiki

The Banner Saga on Steam