The situation PlatinumGames faced while making Bayonetta 2 was completely different from the one they faced making the first Bayonetta. They weren’t a new studio relying on the big names working for them to build a reputation. With games like Vanquish and Metal Gear Rising, they’d established a reputation for themselves; a reputation strong enough to attract attention from Konami (Metal Gear Rising), Microsoft (Scalebound), and Yoko Taro (Nier Automata).

In particular Platinum’s critical success brought them into contact with Nintendo. The development studio offered Nintendo convenient solutions to the problems critics had levied against them for the better part of a decade: weak support from third party developers and a lack of games to attract the lucrative enthusiast market. Hence Nintendo’s willingness to publish The Wonderful 101 and hire them directly to work on their revival of the Star Fox franchise with Zero and Guard.

Between these projects was Bayonetta 2, the centerpiece of that partnership. Not only did the original leave a strong impression in players’ minds when it was released in 2009, but it was the kind of impression that would suit Nintendo’s needs and play into Platinum’s greatest strengths. While supervised by Hideki Kamiya, it was directed by Yusuke Hashimoto, a visual effects designer who had previously worked with him on other projects (including as a producer on the original game.)

Set some time after the events of Bayonetta, Bayonetta 2 begins with several of the main characters (most notably Bayonetta and Jeanne) Christmas shopping in New York City. It doesn’t take long for an Angel fight to break out and interrupt this brief moment of peace. Bayonetta maintains control throughout most of the early moments, but something unexpected happens: one of Bayonetta’s attacks accidentally sends Jeanne’s soul to Inferno. This forces Bayonetta in a race against time to get to Noatun, a mountain town located somewhere in Tibet (or maybe Belgium or Italy; the game is surprisingly unclear on this point); climb the mountain Fimbulventr to open the Gates of Inferno at the top; and break into Hell to retrieve her sister’s soul. Despite the change in setting, most of the cast from Bayonetta (minus Cereza, for obvious reasons) reprise their roles for this story, albeit with minor visual and inflectional changes: Jeanne’s longer hair, Luka’s more strongly pronounced role as a journalist and friendlier relationship with Bayonetta, Enzo’s slight contributions to the plot, etc. Outside them, there are only two new characters introduced for this story:

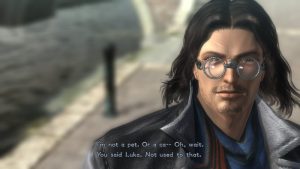

Loki

The deuteragonist who escorts Bayonetta to Fimbulventr and through the gates of Inferno. Narratively speaking, he’s somewhere between Cereza and Luka in terms of his role in the narrative. His cocky attitude and inexperience allow Bayonetta to quip off him when the moment suits it, but he comes across as more sympathetic than Luka ever did. Some of that stems from his importance to the plot, but just as much stems from the competence his abilities gives him. He can control the passage of time in certain areas and he attacks with magic infused Tarot cards. Also, he can transform into a squirrel at will.

Loptyr

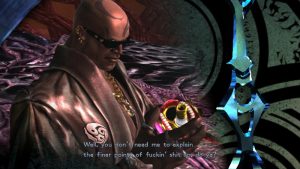

The ultimate antagonist of Bayonetta 2. Since Loptyr operates from afar for most of the story, his motivations remain vague outside his interest in capturing Loki. Other than that, he’s very much a villain molded after Balder: calm, in control, coded religiously, and exuding power in every scene he’s in.

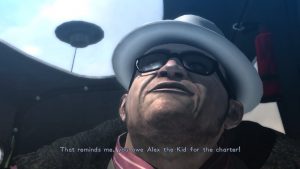

Confident and flamboyant, Bayonetta 2 seeks above all else to have fun with itself. Sometimes that fun is found in a sly cultural reference (this time from sources like Alex Kidd, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, and Futurama) made just for the sake of making it. More often, it’s found in the game’s admiration for action movies, blockbuster video games, and the impossible stunts often associated with both. Stylish cinematics, elaborate choreography, sweeping and purposefully ridiculous set pieces like the one the game begins on – these are what Bayonetta 2 delights in the most, and these are where Hashimoto’s visual design skills are most apparent. Indeed, the game begins with a similar over-the-top spectacle as the first, narrating the back story, before the game begins proper, as Bayonetta fights enemies on the top of a jet fighter speeding over New York City. Naturally, these over the top performances produce the same charismatic pull that they did in the first Bayonetta. After all, if Bayonetta 2 can have this much fun with itself and it’s willing to share that fun with all who seek it, how can you resist taking the game up on its offer?

Yet for as enticing as that charisma can be, most of Bayonetta 2‘s errors can be traced back to overestimating how far this charisma can carry the game. The logic behind the game’s design is conventional as far as video game sequels go: its focus is on adding new features, fixing old problems, and always preserving its predecessor’s core. As conservative an approach as this may seem, there are advantages to it, the most important one being that it guarantees the game a certain level of quality. However, there’s also a risk in designing games like this: because the method is reliant on what the designers identify as the previous game’s core, misidentifying that core can lead the team astray.

Bayonetta 2 exhibits both of these outcomes. It has no trouble replicating the intricate and flashy combat systems that define its predecessor, and the additions it makes to those systems seem sensible enough: a few extra playable characters (some very briefly, some as unlockables), new modes like online co-op, perhaps a few tweaks to the physics, and minor changes to make the game more accessible to a wider audience, like toned down difficulty. The biggest and most noticeable fix is the removable of the immediate-fail QTE segments, but it also scales back on some of the more tedious minigames. The visual style is the same, but it’s brighter and even more dazzling than before. “Fly Me to the Moon” has been replaced by stylish renditions of “Moon River”. And despite being credited in the game, many of the Sega references give way to Nintendo ones, including some costumes (including Star Fox, of all things).

Despite this, something feels off a little off. In identifying charisma as Bayonetta‘s core, Bayonetta 2 overlooks a much more essential force that grounds everything else, including that charisma: Bayonetta herself and all the things she represents. The first game was more or less a character study; its success stems from every facet of its design relating to this alluring figure with so much to say and do.

By contrast, Bayonetta 2 believes these facets of the game strong enough to stand on their own without anything to unify them; or that the Platinum charm is a strong enough force to do just that. Whatever the case Bayonetta 2 ends up a less consistent game because of that judgment. For example, the step down in difficulty makes the Muspelheim segments a better counterpart to the Alfheim because it opens up that part of the game to more people while preserving the core idea.

The same cannot be said for Torture Attacks. Once a major part of Bayonetta’s character, they now exist as an extraneous feature embedded in combat. The new ability, Umbran Climaxes, are partially to blame. This basically amounts to a magic meter that, when filled up and activated, allows even more powerful attacks until the meter is drained. Why bother inflicting a lot of damage to just one enemy when Bayonetta’s magically powered super attacks can zone many enemies at once? Even putting aside Umbran Climaxes, another question concerning Torture Attacks arises: what do they code for this game? For Bayonetta, the answer was obvious. They were the eponymous heroine’s method of sexually humiliating her foes, and the design reflected that, whether it was the S&M themed nature of each attack or the resistance in performing them coding foreplay leading to sexual climax. But between the (perceived) ease with which Torture Attacks are performed here and the smaller number of sexually themed Attacks in general, neither meaning makes sense for Bayonetta 2. If anything, the feature now codes as a frenzied continuation of the action; consistent with the rest of the game, but a flat meaning that doesn’t relate to much outside the game’s sense of style.

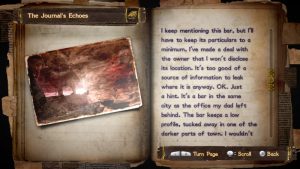

Unlike Vigrid and its witch hunts, what defines Noatun specifically is a little more difficult to answer. This isn’t to say the writing doesn’t try to lend the city an identity of its own. In fact, the lore goes to great lengths to establish water as dense with religious meaning for the citizens of Noatun. Legends of great floods depict those floods as acts of destruction and renewal. And because the waters that bring the floods contain the memories of everything that is and ever shall be, the writing is also tinged with intrigue toward the divine unknowability behind ordinary existence. Of course, why the writing expresses so much interest in the water when the plot revolves around scaling a mountain (whose significance goes uncommented on) is never addressed.

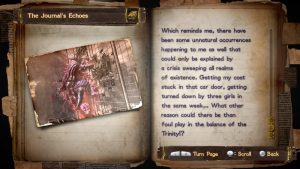

And although it’s made clear that Noatun has a history with the Umbran Witches and Lumen Sages, little is made of the relationship between these groups and the humans that lived there. That relationship is clearly present, judging by the Umbran Resting Places scattered throughout the city. Some even make use of magics only available in Noatun: their remnants are scattered across time, forcing Bayonetta to run through the nearby surroundings collecting all the pieces. Yet the cause for the Witches’ deaths and why so many of their graves are spread across Noatun is never elaborated upon. This gap in the writing is especially conspicuous if one assumes Noatun is located in Tibet, like one of the early cinematics implies.

As the story progresses, the reason why these tensions exist becomes clear. It loses its interest in the eponymous heroine and instead places that interest in the theoretical deuteragonist Loki and all the possibilities he opens up. Over time the story expresses more interest in Loki than it does in the character whose name is in the title, meaning she fades into irrelevance as the game moves to explore the possibilities that Loki opens up. More often than not, it’s his time manipulating powers that drive the plot forward and define the environments, even if he doesn’t have all that much control over his powers. In fact, the plot abandons anything to do with the Umbran Witches and Lumen Sages as the conflict between the Aesir comes to dominate the story, and the thematic flourishes reinforce that: the occasional invocations of the power of free will make more sense through Loki than they ever would through Bayonetta.

Despite the amount of attention he receives, Loki’s role was always meant as a side one, meaning his character, adequate though it may be, doesn’t benefit much from the added attention. But what of the eponymous heroine? With so much of the game’s attention fixated on Loki, there isn’t much left to spare for Bayonetta. The camera has wrested itself free of Bayonetta’s grasp, either focusing on her moves out of sheer coincidence or wandering away from her in favor of what it sees as a more interesting sight. Sexuality is all but evacuated from the game, and as stylish as Bayonetta is, that style wants for context. She is no longer the subject of her own story, but an actor forced to follow another’s direction, making clever quips whenever she can. She’s prone to make significant mistakes and encounter genuine moments of vulnerability she has trouble compensating for.

Take note, for example, of how the plot begins with power inexplicably leaving Bayonetta’s hands (depicted as a mistake on her part) and continues with outside forces compelling her into action. True, one could say these additions were made in the interest of expanding her character to make her richer and more complex. However, it’s an odd argument to make for a game that isn’t concerned with theme, and it assumes Bayonetta’s character was previously lacking depth. With this not being the case, Bayonetta 2’s subtle changes amount to contradicting the very things that make the protagonist appealing in the first place.

Altogether, Bayonetta 2 straightens out many of the rougher edges of the original, resulting in a prettier, more replayable game. But at the same time, the lower level of difficulty is simultaneously welcoming and disappointing (the hardest difficulty level is about par with normal of the original game), and while the action maintains the same level of exhilaration, the characterization and storytelling don’t. It is, like many video game sequels, seemingly perfect on the outside, but still missing something essential. But it’s also a fundamental problem with a game this over-the-top: at the end of the original Bayonetta, the heroes summon a demon to punch the universe’s creator and send its soul flying into the sun. How do you even follow that up?

The irony of all this is that Bayonetta 2‘s straightforward approach paints a complicated picture not only within the game, but outside it as well. On the one hand, the game solidified Bayonetta’s success as a character. Nintendo would later include her as a fighter in Super Smash Bros. for Wii U and 3DS and critics lavished praise on the sequel for, in their eyes, polishing an already successful formula.

Unfortunately, Bayonetta 2‘s critical success wasn’t matched financially, as the game didn’t quite light up the sales charts. It’s hard to extrapolate much from this; there are just too many factors at play to draw neat conclusions. What is clear is that Bayonetta 2‘s situation signaled a shift in Platinum’s plans toward smaller, safer (often licensed) projects that would keep the company afloat: Transformers, The Legend of Korra, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

As Nintendo was responsible for funding the production of Bayonetta 2, it has only been released on the Wii U, though a Switch port is due in 2018, bundled with its predecessor, and leading up to a third game down the road.