Revolution Software was founded by Charles Cecil, Tony Warriner, David Sykes and Noirin Carmody in England in 1990 as a reaction to Sierra’s adventure games. Their reasoning was simple enough – they thought they could do better. Their first game, Lure of the Temptress, failed to light many fires, but their second game, Beneath a Steel Sky, quickly became a cult favorite, and time eventually recognized it as a true classic of the point-and-click genre.

Beneath a Steel Sky takes place in futuristic Australia, with most of the population living in huge, corporate-run cities, with a small group of outliers living in the wilderness known as The Gap. The intro, told in comic book-style panels with artwork by artist David Gibbons (The Watchmen), who also drew all of the backgrounds, tells the story of a young boy whose helicopter crashes in The Gap and is raised by the aboriginals. Remembering only his first name, Robert, they give him the surname “Foster”, after a beer can they find (a joke lost on American audiences due to some changes to avoid trademark infringement – the beer brand became “SS IPM RAW” or “Warm Piss” spelled backwards). Foster is a bright boy, and manages to create a robotic friend named Joey to keep him company. Soon, he grows into adulthood, when a helicopter kidnaps him and takes him back to the expansive urban jungle known as Union City. Things get further complicated when his transport crashes yet again and Foster is left as the only survivor. If that trauma wasn’t enough, the local police have classified him as a terrorist and begin hunting him down. Foster gets even more confused when the policeman sent to apprehend him is fried right before his eyes, as if some unseen force was protecting him. With nowhere to go but down, Foster descends through the towers of the city to find some answers.

Union City is socially stratified into various different levels, with the poor, blue collar workers practically living in factories at the top level and the rich upper class living at the bottom in fancy apartments. The whole of the city is controlled by LINC, a computer which not only monitors every aspect of life, but has apparently also taken on a consciousness of its own after melding minds with one of its creators. Foster himself is subjected to quite a bit of culture shock, both due to the excessive governmental control and the weird folks he runs into.

Much of the story of Union City is told by its inhabitants. At the top are the shop workers, like the slightly disgruntled Hobbins, who doesn’t really care who you are as long as you don’t mess with his stuff. (This being an adventure game, it’s naturally something you need to do.) In other areas, you’ll find more bored and apathetic employees, enamored with seemingly inane minutiae like their clipboards and uninterested of the workings outside of their own immediate circle. At the top of this bureaucracy sits the game’s most amusing character, a boorish plant supervisor named Gilbert Lamb, who trots around in a garish fur coat (“made from the last ten beavers in the world!”, he brags) while his lowly workers toil in grey jumpsuits. He’s so fat that you can actually see his double chins rendered in glorious low-res VGA. He also knows little, nor cares, about what his factory actually does, but enjoys the status that his job title provides despite the fact that it’s not entirely clear how he got there. It’s a fun little satire of corporate culture, which works to tie in how closely Union City’s dystopic world is to our own reality. At any rate, messing with Lamb is probably the most fun part of the game, as you can drain his bank account and demote his social status, much to his chagrin. One of the game’s only real faults is that there isn’t more of him.

There are a number of other quirky characters. In true cyberpunk fashion, in order to interface with LINC, you need to get an operation to get a port installed in your head. This is done by one Dr. Burke, a deranged maniac who huffs his own anesthetics. He has a patient in his office with a gaping hole in his chest, which he routinely fiddles with. (You can talk to the bed-ridden man, who’s still conscious – apparently he doesn’t mind at all.) You can only afford the operation by donating organs, but since you spent your life in the wilderness, free of urban pollution, you’re simply far too healthy and your body parts would fetch far too much money. In return, you have no choice but to donate your testicles – which, the doctor politely informs you, are thankfully harvested after your death.

Further down the line, you accidentally end up as a defense attorney in court case for Hobbins, who has been ineptly framed due to some of your earlier mishaps. The judge seems to think the whole thing is sort of game show, further convincing Foster that everyone has gone mad. You also need to request the aid of one Mrs. Piermont, the richest (and fattest) woman in the city. Revolution Software apparently felt the character was so amusing that she (or perhaps a long lost, distant relative) shows up as another minor character in their next game, Broken Sword.

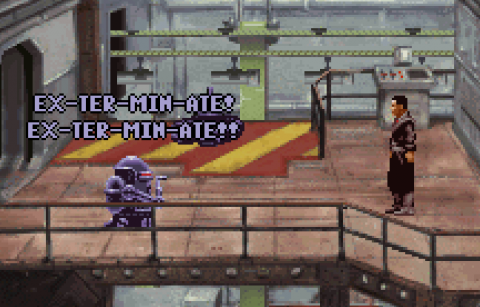

And of course, there’s Joey, your robotic companion. You escape from The Gap with his circuit board, which you can place in various different shells throughout the course of the adventure. He’s initially quite disappointed – and suitably sarcastic – when you stick him in a dumpy little cleaning model, but gets considerably more excited when inhabiting a welding robot, where he does his best Dalek impression. (“EX-TER-MI-NATE!”) He’s easily one of the best lil’ buddy robot companions since the lovable Floyd from Infocom’s Planetfall/Stationfall text adventures.

Most of the characters are brought to life by the excellent voice acting in the CD-ROM version. Foster has a cool voice, although some of his line readings are a bit awkward – perhaps intentionally so, to illustrate his naiveté. It still doesn’t explain how he has an American accent, or why everyone else has various British accents rather than anything Australian, but even extremely minor characters, like the goofy cops Sam and Norbert, remain memorable. If anything, a lot of the characters feel underwritten, and dialogue options are exhausted before you feel like you’re done talking with them. And much like comics books, which tend to bold certain words for emphasis, Beneath a Steel Sky capitalizes them in the subtitles. This, of course, looks a little bit odd.

The game’s all a bit on the silly side, despite its oppressive atmosphere – even the music is a bit jaunty – but things get a bit more serious once you infiltrate the long abandoned subway tunnels to uncover the mysteries of LINC. In addition to reading news at the local terminals, you can also jack into the system and walk around cyberspace. Here, Foster is represented by a blue avatar, and all of the inventory objects are replaced with various commands, programs and documents. You need to jack into this space a few times, each using different ID cards to decompress and decrypt various files that you find.

Beneath a Steel Sky uses an enhanced version of the Virtual Theatre engine used in Lure of the Temptress. The NPCs are given simple scripts that determine their patterns, so they walk around rather than sitting in one place. It was immensely awkward in Lure of the Temptress, but here it’s used for an appropriate amount of realism, and it’s never too tough to track someone down, because they’re never more than a few screens away. The interface is quite simple, with left clicks looking at objects and right clicks interacting with them.

The game’s not terribly long or terribly difficult, although a number of puzzles involve timed elements, absolutely requiring that you bring up the status menu and set the speed to the absolute lowest setting in order to get things done. There are a few cases where you can yourself killed – including one right at the beginning if you’re not careful – but generally death only comes if you’re not careful enough to avoid the warning signs. For example, when wandering in the sewers, there’s a foreboding crack in the wall. Walk past it, and some kind of horrible creature grabs you and pulls you to your death. It’s almost better to save just to see this, because you never see the monster other than its claws and eyes, nor is it ever referenced at any other point in the game. It brings you to wonder – just what kind of crazy experiments is LINC doing?

Other than those nitpicks, there’s not much to complain about, and a whole lot to praise, especially the writing. This delicate balance between humorous writing and serious storytelling carried over to the Broken Sword games, the series which Revolution Software primarily concentrated on. Charles Cecil has stated that he’d like to do a sequel, which would be excellent, especially considering there’s enough backstory involving the war between the corporate cities to tell an interesting tale. For now, we’ll have to do with the slightly enhanced iOS version, released in 2009, which cleans up some sound and adds some new artwork in the cutscenes, also drawn by Dave Gibbons. It’s a good port and includes a hint function, but is sadly missing the speed controls of the initial release. The original version of the game has been made freely available, and can easily be played via ScummVM.