- Black Mirror, The

- Black Mirror II

- Black Mirror III

- Black Mirror

The Black Mirror, known as Posel Smrti or Messenger of Death in its home territory, is said to be the best Czech adventure game ever made. That may speak more to the state of the adventure game scene in the Czech Republic than The Black Mirror‘s quality, but this awkward game from the fallow period in point-and-click adventure history isn’t without its charms. It managed to be popular enough among a small but committed following to spawn two sequels from a different team in 2009 and 2011, as well as a reboot in 2017.

The common narrative around point-and-click adventure games is that their heyday was the early to mid-90s and then they pretty much died out for about a decade and a half until small studios like Wadjet Eye Games reinvigorated them with sleeker, modern design philosophies and groups like Telltale Games shifted away from puzzle solving to spin the genre off into experiences that focused more on cinematics, moral choices and quick time events.

This narrative isn’t completely untrue, but it’s misleading to say the genre died. It’s true that adventure games fell from their pedestal in the gaming world. True what were once industry giants like Sierra fell hard out of the limelight. True these games had an awkward transition into the 3D era, with the likes of Broken Sword eschewing gorgeous cartoon animation for blocky polygons. And true these slow, often clunky games seemed behind the times as more powerful systems allowed for faster and more dynamic approaches to gaming to take hold. But adventure games they never totally went away. They just became increasingly niche, popular mostly within European markets and in indie circles.

If you were an adventure game developer in the early 2000s, there’s a good chance your game would be published in North America by The Adventure Company. A Canadian branch of DreamCatcher that launched in 2002, The Adventure Company unsurprisingly specialized in adventure games. It worked in partnership with game developers like Kheops Studio, THQ, Microïds, Cryo Interactive, and Darkling Room to put out some of the most recognizable adventure titles of that era: Syberia, Broken Sword: The Sleeping Dragon, Dark Fall: The Journal, and several Agatha Christie adaptations to name a few.

The Czech group Future Games was one developer that collaborated with The Adventure Company. Future only put out eight games – one of which was a remake of an earlier title – in the 15 years it was active, and almost none were especially big sellers. The exception was the 2003 Gothic horror game The Black Mirror.

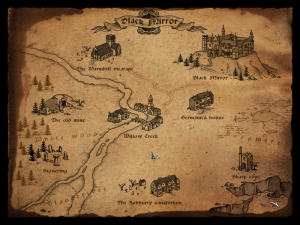

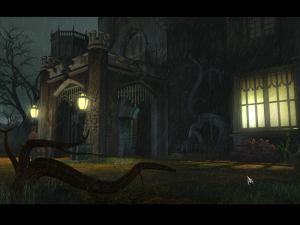

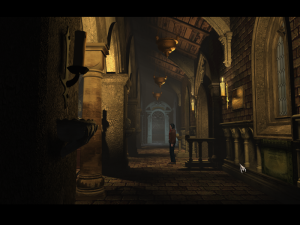

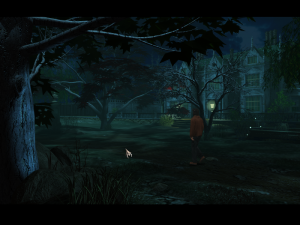

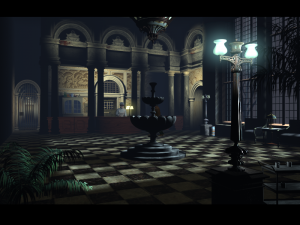

Set in Suffolk, England in 1981, The Black Mirror puts you in the shoes of unhinged weirdo Samuel Gordon. (The reason for that description will become clear in a minute.) Samuel has been forced to return to his ancestral home the Black Mirror, a large and decrepit manor, after 12 years of estrangement following a tragic event that took the life of his wife.

Samuel’s grandfather William just died under mysterious circumstances. William’s death is considered a suicide, but Samuel suspects something foul afoot. As he begins to learn more about his grandfather’s occult and arcane interests, Samuel realizes there may be a curse upon his family’s lineage. Matters are only made worse when people around the Black Mirror start getting viciously murdered.

So to start, let’s talk about Samuel. Adventure game protagonists are infamous for their utter disregard for tact and ethics. They seem capable of doing anything to accomplish their goals, from drugging a neighbor’s dog in The Blackwell Legacy – which, to be fair, developer David Gilbert has expressed regret for – to getting a polar bear to sexually assault a man who’s in your way in Runaway 2: Dream of the Turtle. Even ostensibly likable ones like Broken Sword‘s George Stobbart are often jerks for no reason.

But Samuel Gordon may take the cake. In the game’s six chapters, Samuel will bribe officials, break and enter into numerous private properties, sabotage his uncle’s scientific experiments, impersonate a priest to listen in on someone’s confession, tamper with evidence at a crime scene, start a fire in a mental hospital, electrocute an innocent man to rob him, drug a man to rob him, damage a groundskeeper’s equipment to rob him, and dig up two graves to – wait for it – rob them.

Although the dialogue does let us know Samuel is kind of an insensitive snob, there’s never quite enough justification for why he’s totally comfortable being this way. A late reveal might inform it, but it’s never remarked upon much until then. Suffice it to say, do not get between this man and his objectives.

This wouldn’t be so remarkable if it didn’t in fact get in the way of gameplay. Some puzzle solutions would not occur to the player unless they’re completely depraved. Consider the mental hospital fire. Just speaking hypothetically: If you needed to gain entry somewhere and the only way in was through the boiler room, would your first impulse be to clog up said boiler with a pair of rubber boots and risk burning down an entire historical structure, potentially killing everyone inside, just to do it?

So as advice to the player: If you think up a solution but don’t think it’s right because it’s possibly too sociopathic, try it anyway. You may be surprised.

The Black Mirror‘s puzzle design starts out intuitive. Even a novice adventure game player probably won’t be checking a walkthrough for the first couple chapters. But it gets increasingly obtuse as the game goes on and more areas open up. You are often left directionless, wandering from place to place hoping an event triggers. There’s some pixel hunting, Runaway syndrome – when you can’t pick up an item until you see where it needs to be used, but are given no indication that you should go back and get said item – and abrupt instant death scenarios without autosaves to make matters worse. There’s also a maze with identical-looking passages and sudden death toward the end and – gasp! – a “slide the piece of paper under the door and push the key out of the keyhole” puzzle.

The game uses both right and left clicks for no real reason. Like usual for the medium, right clicks are for observation and left clicks are for interaction. Sometimes you have to observe and then interact, but sometimes the interaction is itself just an observation. So there’s no real reason to have the two buttons. The sequels remedy this, thankfully.

Future Games also made the horrendous decision to have two instances when Samuel has to wait for a character to finish a task, but instead of simply fading to black and saying X amount of time has passed, the player has to wait five to ten real-time minutes to progress. But you can’t just get up from the computer and wash a few dishes, because you also need to wander around from location to location while waiting. At least the developers put in fast-travel, with double clicks sending you instantly to the next screen.

On the other hand, the developers had the nice idea that unless that unless a hotspot is still needed for a puzzle, observations go away after clicking on them once. Which means the screen isn’t constantly cluttered with unnecessary clickables, helping in however small a way to zero in on what you’re supposed to do next.

The worst design decision is the wolf puzzle, which can straight-up break the game. You’re in a mine shaft and need to pass a padlocked door and then some angry wolves. You are given a gun with two bullets to do so. But unless you do something to sharpen your aim first, you miss the first time you try to shoot the padlock. So you end up using both bullets to get through the door, and have none to get rid of the wolves. You’re given no indication that this will soon bring you to a no-win scenario. If you saved after missing the first shot, there is no way to continue on in the game. Thankfully fans have kept save files uploaded online to help the hapless player who might find themselves in this situation.

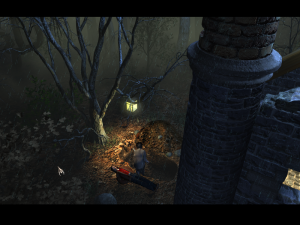

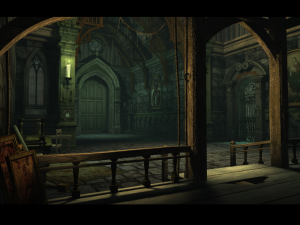

The game is locked to 800 x 600 resolution, but the backgrounds are gorgeous and ooze atmosphere. Great sound design, too, a consistent quality for the series. It makes use of haunting ambient music to really nail the Gothic mood. Unfortunately the 3D characters look really ugly. Samuel’s character design is uninspired and awkward, and everyone moves in a choppy, stilted fashion.

One can sum up the voice acting by saying that it placed fourth on British gaming magazine PC Zone’s “Top 5 Games with Crap British Accents” list in a January 2008 issue (Hellgate: London received first prize). PC Zone editor and critic Will Porter also effectively summed up the dialogue itself, calling it “rambling, stereotypical, mistranslated and acted out in the style of a Jackanory presenter reading the extended essays of Karl Marx.” (Jackanory was a BBC children’s show intended to get kids interested in reading.)

There’s little to say about the plot except that it’s a serviceable carriage for the atmosphere. It draws inspiration from H.P. Lovecraft, but more along the lines of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and “The Thing on the Doorstep” than his Cthulhu mythos stories. It won’t make your jaw drop, barring the plot holes that you can drive a truck through (the most glaring of which is a murder that occurs when the killer could not physically have been anywhere near at the time), but there’s a pleasant familiar spookiness to the whole affair. Fog and rain and broody castles and people with secrets. Interrogating people and finding clues until the pieces all come together. It’s actually fairly long for an adventure game, clocking in between 10 to 15 hours for most players. And the depth of detail that went into the setting makes returning to it all the more rewarding in the sequels.

Like every game in the series, the ending is abrupt and unsatisfying, but the journey there is entertaining more often than not if you’re willing to forgive a lot of older adventure game vices. Computer Gaming World gave The Black Mirror a contemporaneous rating of two stars out of five in its February 2004 issue, pithily describing it as “Gothic horror that doesn’t require much reflection.” And that assessment is still pretty much true today. The Black Mirror doesn’t “hold up” so much as it encapsulates a lot from this forgotten era in the point-and-click adventure genre, warts and all.

Future Games has a history similar to many of adventure game studios in the 2000s (including Cranberry Production, the one that would turn Black Mirror into a franchise half a decade later): The company saw modest success within a small market, then eventually petered out and closed down.

Future was established in 1999 to develop and sell computer games in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. That year it released a DOS remake of a ZX Spectrum platformer called Boovie and its first adventure game Messenger of Gods, which would later be remade and released in 2005 as NiBiRu: Age of Secrets. It started production on The Black Mirror in 2001 and released it after a two-year development cycle. It was positively received and sold well in the Czech Republic and, with The Adventure Company’s backing, garnered some financial success abroad as well. The company would go on to create the RPG Bonez Adventures in 2006 and branch off into Czech games distribution for the RPG Night Watch that same year.

Future’s final three games were Next Life, a pretty decent sci-fi adventure game with a premise similar to the TV show LOST, in 2007; Tale of a Hero, a fantasy adventure that was never released in English-language markets even though its Italian version includes English voice acting and a patch for English subtitles, in 2008; and finally the murder mystery adventure game Alter Ego in 2010. Alter Ego was poorly received and didn’t sell well, prompting the studio to close down in September 2011.