For all of their tremendous success, Blizzard, which would eventually become part of the Activision-Vivendi conglomerate, hasn’t exactly been the most innovative game developer on the block. Rock and Roll Racing was really just a half sequel to Radical Psycho Machine Racing, which in turn was little more than an ode to Rare’s RC Pro Am. Warcraft basically just took the template from Westwood’s Dune II, Diablo is a modernization of Rogue-like dungeon crawlers, and World of Warcraft – their cash cow – is more like “Everquest Done Right”. Their only truly original games have been the two The Lost Vikings games.

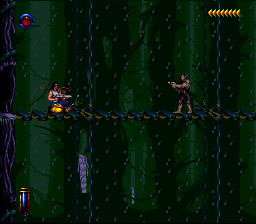

And then there’s Blackthorne, also known as Blackhawk in Europe. Blackthorne is essentially Prince of Persia With Guns. There was technically already a Prince of Persia With Guns, officially named Flashback, which was developed by Delphine Software. It was an outstanding game that also borrowed liberally from Out of This World, another game developed by the same company. However, its sequel, Fade to Black, was a terribly mishandled early 3D action/adventure game, so we’ll take Blackthorne as a much more likely successor to Flashback, even though it’s not quite as good.

The plot of Blackthorne is lowest denominator comic book schlock. (The art itself is provided by comic book artist Jim Lee.) The hero is actually born of an alien planet named Tuul, but was sent to Earth as a child. Having eventually worked his way up through the military, he is informed of his past and shuttled back to save his home planet from danger. There are cutscenes involving the insidious Sarlac and company, who look quite a bit like the orcs from the (not yet released) Warcraft, whose names are randomly interspersed with apostrophes for that extra bit of guttural pronunciation flavor. You should probably skip these.

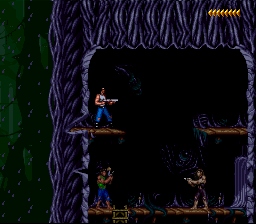

It’s much better to simply imagine that you’re playing a video game based off an 80s heavy metal song. (On that note, it would be awesome if some triumphant game developer will pick up the torch and create an action/RTS adaptation of Iron Maiden’s Run to the Hills.) And why not? The hero is a long-haired asskicker, a boyhood power fantasy personified, who could potentially scare his mom into believing he’s a Satan worshipper. All of the hostages, who are only distinguished by the color of their pants, look like strung out members of a washed up glam rock band. There is good, and there is evil, and there is good, quite literally, shooting evil in the face, several times over.

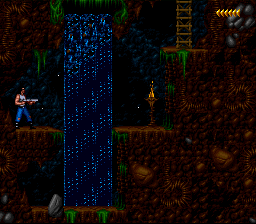

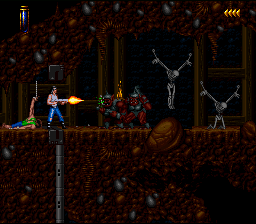

Blackthorne’s main dealer of destruction is a shotgun, which is cool enough. More interesting (and deadly) is the cover system. By equipping your gun and holding up, Blackthorne will dive into the background in a defensive pose. This works anytime, anywhere – you never need to actively “find” cover, because it’s always there. When hiding in the shadows, you can’t be hit, but you also can’t attack – you’ll need to duck out for a quick second to fire. Of course, these same rules apply to the enemies. What’s important to remember is that there’s a brief moment after firing that they’re vulnerable, when they reload their gun. At first, it’s simple enough to just take cover, wait until your enemy fires and then quickly deliver a return shot during this split second. If you screw up and take a hit, most of the enemies will drop cover to mock you, essentially granting you an easy revenge shot.

Naturally, it gets more difficult as the game progresses – at the start, the bad guys will fire a set number of shots before reloading, but eventually, it’ll become random, forcing you to think on your feet. And soon enough, you’ll come across enemies that don’t need to reload at all. With tougher enemies come better weapons, as you too obtain new shotguns, which enable rapid fire, eliminate the need to reload, or shoot explosive shells. This actually works way better than Flashback, which required split-second precision to activate a shield to absorb enemy fire. There’s a pleasant, powerful rhythm behind it, and makes the gunfights one of the key experiences in Blackthorne.

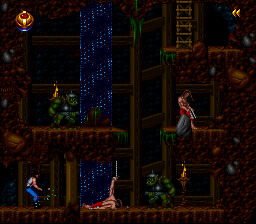

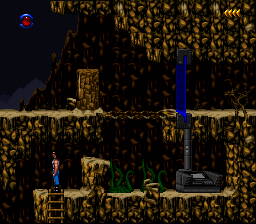

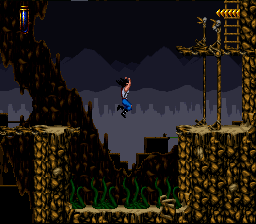

Much of the game also revolves around platforming – that is to say, jumping, climbing, leaping, hanging on ledges…basically, the same thing as Prince of Persia. It also inherited its sluggish, awkward control scheme, although to be fair, it’s also a bit tighter and more responsive. It is, however, hampered by its limited input. You can switch between “unarmed” and “armed” modes at the hit of a button, but each mode has completely different control schemes – the general “action” button is used to either run or shoot your gun, case depending. You also cannot run or jump with the gun equipped. It’s also far too easy to accidentally use special items like bombs, which is especially annoying since they’re in limited quantity, and it’s possible to find yourself in unwinnable situations.

Additional items include Hornet Bombs, which can be controlled remotely to destroy things in remote locations – usually shield generators – and Levitators, dorky-looking devices that let you reach higher areas. Most of these are used in solving the “puzzles”, although there’s barely a puzzle to be solved that doesn’t involve blowing something up somewhere. At most, you’ll be subjected to time trials, as in the “make these jumps before the door closes” kind you’ve probably seen before.

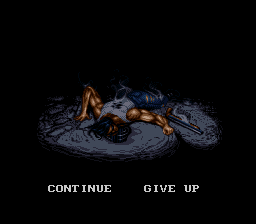

The problem with Blackthorne lies in its repetition. There’s very little graphical variation in the levels, and there are only changes every few stages. Furthermore, there aren’t any checkpoints, causing you to start the level from scratch upon death. There are usually a bunch of health restoration items to be found, but it’s all too easy to misjudge a jump and screw up everything entirely…and there are some long levels. The nature of the game doesn’t really lend to replay either – those stop n’ pop gun battles are fun the first time, but they tend to drag on the fifth or sixth time through the level.

So Blackthorne is fun, a not-quite-classic-but-still-pretty-good-game, but it’s really that atmosphere and animation that sell it. Back to the Atari 2600 games, you were lucky if your stick figure was animated in any recognizable fashion. In the 8-bit NES days, Mega Man would blink if you let him stand still, and that was pretty outstanding. But the expanded graphical capabilities and storage space during the 16-bit era allowed for programmers create additional animations to add to the personality of your player-character. This was how Sonic the Hedgehog really took off, with his “what the hell are you doing?” look if you stood still, or his teetering animation if you were next to a cliff.

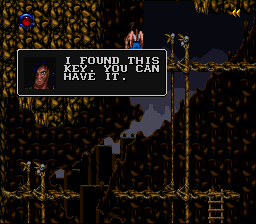

If Sonic the Hedgehog is a ten-year-old’s version of Way Cool, then Blackthorne is the thirteen-year-old’s version. Here, the hero is armed with a shotgun. If you shoot an enemy, they’ll collapse satisfyingly to the floor, and, if you’re playing a version that isn’t on a Nintendo platform, some pixels of blood will squirt out. There are also prisoners lying around the place. You can kill them, if you want, and there are no direct consequences to it. At the same time, there’s no advantage either, and you can miss out on important and/or useful items. Sometimes they’re positioned directly in the line of fire, which poses a moral challenge – you can try your reflexes to kill the enemy before he can get a shot off, you can use the prisoner as a meat shield to absorb a bullet before counterattacking, or you could just ignore him completely and let him die.

Again, there’s no real punishment if these guys die, and you’re not even guaranteed a reward if you save them, but it’s an interesting ethical compass, one that usually isn’t measured in console games. Remember, this is years before Grand Theft Auto and other similar games, where murdering innocent people is something the player simply does for fun. In most old console and arcade games, the only innocents to kill were in light gun games, with the detriment being loss of points and/or life. Here, it’s just something you can do to be “bad”. There are more interesting ways to be cool, though – there’s a blind over-the-shoulder attack, where you can shoot enemies directly behind without turning to face them, Army of Darkness-style. Though hardly useful (it’s not much slower to just turn around and shoot regular style), it does look neat.

Blackthorne was initially released for the SNES and PC around the same time. It’s pretty clear that it was developed for the SNES then lazily ported to the PC – there’s no real save function, only passwords, and it’s lacking a real control config. On the other hand, the PC version has some gore effects that were censored out of the SNES version. The SNES version mostly has an atmospheric soundtrack, but the PC version is the only version with actual music running throughout the game. It’s all MIDI, but it’s pretty good. Also, since the game was designed for the low SNES resolution, the remaining portions of the screen in the PC version are taken up by the inventory bar. Otherwise, the games are essentially identical.

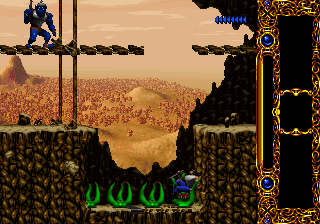

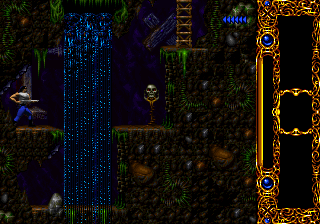

On paper, the 32X version should be the definitive port, considering it has higher color graphics and four new levels, which take place on a snowy mountain. In practice, though, it’s a bit lacking. The visuals are inconsistent – the backgrounds look fantastic, and there’s a lot of extra detail that helps make the game look less drab. On the other hand, the sprites are terrible. Not only are they computer rendered, but the proportions are ridiculously off, so Blackthorne has gigantic shoulders and a tiny head, and Sarlac kinda just looks stupid. The soundtrack tries to be like the SNES version, but the FM synth of the Genesis sound chip just isn’t up to it, and it comes off as really quite pointless. (Why couldn’t they have just used the music from the PC game, which sounded perfectly okay even as FM Adlib?) There’s actually blood in this version, but it’s not quite as copious as it was in the PC release. The game was actually ported by Paradox Development as opposed to Blizzard themselves, which probably accounts for its sketchy quality. This version was also later ported to the Mac, running in doubled resolution. The backgrounds, however, are just upscaled and the hideous sprites look none the better.

Blackthorne was also ported to the Game Boy Advance, along with The Lost Vikings and Rock ‘N Roll Racing, two of their other 16-bit games. The major problem is that Blackthorne‘s stages consist of static screens. Since the GBA resolution is too small to fit the entire screen, instead it zooms in and forces scrolling. In addition to looking exceedingly ugly, it also forces too many blind falls or jumps. The brightness has been turned up to nullify the lighting issues from the original GBA, but now it just looks washed out and nasty. The controls are awkward, since some of them are mapped to the shoulder buttons, and the animation has taken a huge cut. It’s pretty bad, mostly because it just isn’t suited for a portable platform without receiving a massive overhaul.

Blizzard released the PC version (packaged with DOSBox) as a free download in November 2013. Get it here!

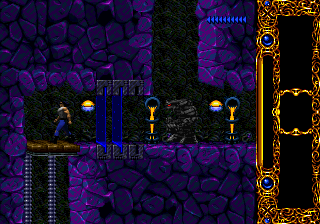

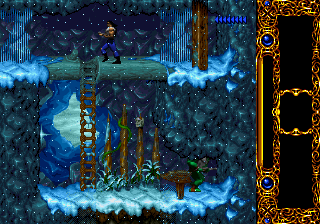

Screenshot Comparisons