- Blade Runner (1985)

- Blade Runner

Co-authored by Harry Milonas

An acclaimed science-fiction writer with a strong cult following, Philip K. Dick is recognized as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century. In 1968 he published Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, telling the story of Rick Deckard, a special policeman in charge of hunting down and killing androids. There was immediate interest in turning the novel into a film, but the process took nearly fifteen years. The film was released in 1982, shortly after Dick’s death. Directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, the adaptation was entitled Blade Runner. It divided critics upon its release and was not initially a financial success. However, the film achieved a cult following of its own, and it popularized the genre of future noir.

Blade Runner’s iconic status has led to its adaptation in various media. There were several written sequels, multiple comic books, and two video games. The first, released in 1985 for various home computers, is an interesting but forgettable action game. The second, however, is an adventure game, and manages to be an exceptional example of both the genre and of licensed games in general. It was developed by Westwood Studios, which used its resources to create a game as true to the source material as possible, succeeding brilliantly.

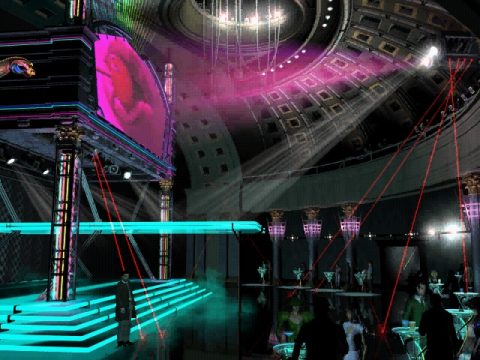

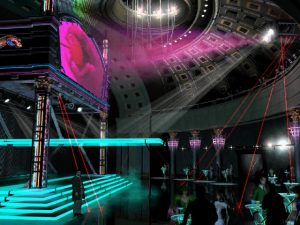

The year is 2019. The location: a bleak neon-lit Los Angeles, with an ever-present pollution problem and a smiling geisha winking from every advertising blimp. In this dystopian future, a special unit of LAPD detectives called “Blade Runners” sweeps the streets of rogue “replicants”: bioengineered soldiers and servants of off-world space colonies, possessing the intelligence and aesthetic attributes of a human, but with all the extraordinary strength and agility endowed by their artificial insides, balanced out by a built-in four-year lifespan. Produced by the Tyrell Corporation, the Nexus-6 models of these colloquially-named “skinjobs” have developed an arguably larger lust for life than their human creators, along with a tendency for escaping their designated posts and attempting to blend in with “normal” society on Earth. This desperate rebellion is deemed illegal and is grounds for execution – officially referred to as “retirement”.

While Westwood’s Blade Runner doesn’t give players the chance to wear the weathered trenchcoat of Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard, its events take place along a parallel timeframe, and in some cases, within areas and beside characters from the film. As one of Los Angeles’ freshest Blade Runners, it’s up to Ray McCoy to hunt and retire another group of four replicants who have hijacked a moonbus, escaped back to Earth, and commemorated their return by harming the increasingly rare and non-synthetic members of LA’s domestic animal kingdom. The “pet detective” premise of Westwood’s Blade Runner sounds underwhelming when compared to the film’s opening scene of a deadly replicant’s escape from discovery. However, the symbolic importance of animals in future LA’s society is a central theme from the original story that was glossed over in the film, and demonstrates the holes in the Blade Runner world Westwood attempted to fill in to enrich its context and setting.

The script (co-written by David Yorkin, son of the film’s co-producer Bud Yorkin) includes stopping the source of terrorist attacks made upon the Tyrell Corporation; discovering corruption among the ranks of the police department; and ultimately clearing McCoy’s name after being framed for murder. At some point in the process, players will have to also define Ray’s humanity, and in turn, realize the fates of the replicants McCoy is hunting are tied with his own. Ray is also accompanied by Crystal Steele, a hotshot police officer in the LAPD Blade Runner unit, and McCoy’s would-be partner or competition in the investigation, depending on how well the player takes to her condescending “advice”. Crystal’s disposition toward replicants is appropriately far clearer than McCoy’s, bordering on an obsessive need for android genocide. Needless to say, if the player decides to show sympathy for the skinjobs, Steele will lose what little respect she shows for McCoy. Her trigger finger works on a similar scale of morality. Additional supporting characters include Clovis, the leader of the suspected animal-killing group of replicants, who bears a resemblance to Roy Batty from the movie; Lt. Edison Guzza, Ray’s boss, whose sleazy outgoing persona doesn’t do much to dissuade players of his possible ulterior motives; and Lucy Devlin, a 14-year old orphan who is implicated in being in league with the replicants, which confuses her already deep-seated self-doubts regarding her identity.

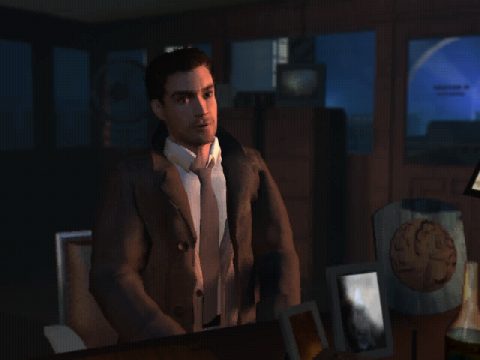

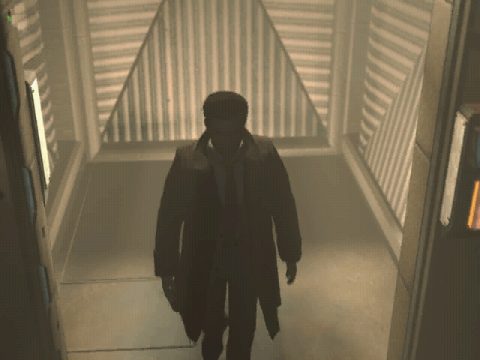

Under the direction of executive producer/art director Louis Castle and lead artist Aaron E. Powell, the game’s art design is spot on as well, capturing the visual style of the film perfectly. The Los Angeles of 2019 is a dark, dirty version of our future. Walking through – or, via McCoy’s genuine police-issued spinner, fast-travelling to – every familiar building and location from the film flawlessly supports the immersive believability of the game’s license. Other elements, such as the spinner vehicles and the glowing umbrellas, further immerse you in the film’s familiar world. The game was advertised as the first “real-time” adventure game, and this might be taken as meaning the passage of time strongly affects the game, like in The Last Express. But this is not the case, and instead refers to the way that the characters are rendered in real-time, using a method called “Voxel Plus” which created the illusion of three-dimensions. The game’s native resolution of 640×480 is an unfortunate victim of the future proof-less nature of classic PC games, and does little to compliment the efforts of Westwood’s backdrop artists. Worse yet, the already crude character models – a side-effect of the then processor-intensive requirements of rendering voxels – unsurprisingly look best at a distance, but slowly show their blurry, pixellated, low detail features and animations when placed closer to the foreground.

Unable to use the film’s original soundtrack by Vangelis, Westwood composer Frank Klepacki recorded a duplicate of the score as well as original tracks done in its style. Between the rain beating down outside, and the familiar cues of “Blade Runner Blues” heard as looking out onto the city from McCoy’s balcony, the faithfulness is overwhelming. Several actors returned to their roles for the game, including Sean Young (Rachel), William Sanderson (J. F. Sebastian), and Joe Turkel (Eldon Tyrell). The rest of the voice work is well-cast, with talent such as Lisa Edelstein (House, M.D.), Mark Rolston (Aliens), and Pauley Perrette (NCIS).

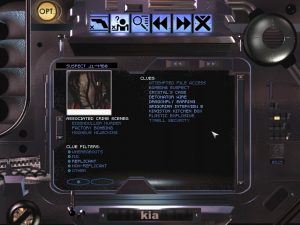

The gameplay has a simple point-and-click interface. You click on a spot to have McCoy walk there, double click to have him run. The story is divided into acts, and you can complete the steps necessary to conclude each act in almost any order you choose. The game doesn’t allow itself to become unwinnable, but it will kill you in a random fashion just often enough to keep you on your toes. Unlike most adventure games, Blade Runner concentrates much more on solving the overall crimes than it does on solving smaller puzzles. In fact, there are hardly any typical puzzles in the game at all, as almost every obstacle is solved through conversation or exploration. The rare moments where you have to employ methods from other adventure games are unexpected and therefore strangely difficult. You also lack a traditional inventory, and instead have access to a database of clues gathered from crime scenes, interviews, photographs and more. The clue database, dubbed KIA, is sortable and extremely helpful in deciding what to do next. The game is fairly difficult as it is; without the KIA, it would be almost impossible.

Conversation is handled in an interesting manner, where you pick “tones” rather than specific lines of dialogue. Choosing “Polite” will see McCoy lack an investigative spine, to the point where he never pressures suspects, and goes out of his way to warn replicants of Crystal Steele’s approaches. Conversely, “Surly” McCoy suspects almost everybody, showing a low tolerance for replicants and as such is practically Steele’s best friend. Unsurprisingly, “Normal” is the most balanced and arguably dull mode, with McCoy towing his behavior between “Polite” and “Surly”. Players selecting “Erratic” however, will have McCoy’s displaying borderline multiple personalities, with his words and investigative techniques chosen at random with every situation, despite any established predilections.

The mood and dialogue that McCoy dishes out are only as significant as the responses he receives from non-player characters. Finding these characters is a variable quest in itself, as they possess their own schedules and “lives”, and will not necessarily be always standing around where the player first encounters them. For example, the portly Lieutenant Guzza is found more often than not at the L.A.P.D.’s cylindrical skyscraper sitting behind the desk in his office. On the chance it’s empty, McCoy may bump into him, under more suspicious circumstances, on the streets of LA. The schedules of NPCs can also leave an impression on the environments: regardless of the competitive Crystal Steele having her own case to worry about, the remains of her favorite brand of cigarette can sometimes be found at a crime scene. Used as a foreshadowing reminder that she is one step ahead of the player’s efforts, such environmental clues are cleverly subtle plot devices, and sell the illusion that the world still moves, even without McCoy’s input. For the astute clue collector, it’s possible to hear references to and even spot a glimpse of Deckard.

Many aspects of the movie are featured in interactive form: the Esper machines and the Voight-Kampff tests. The Esper is an odd machine that allows the user to examine a photograph in a way that seems impossible. When you insert an image you are somehow able to view the face of someone photographed from behind, or clearly see a person standing around a corner. It’s scientifically improbable, both in the film and here, but cool to use.

The Voight-Kampff tests, used to determine whether the subject is replicant, are an engaging mini-game in themselves; a cinematic suspenseful balance between asking the right questions and making sure not to aggravate the suspect, thereby terminating the test. In any event, after confirming the identity of a replicant, McCoy can share the results of the test with the suspect, and subsequently decide whether to calm them down, “retire” them, allow them to flee, warn them of Crystal Steele’s approaches, or even join them in their rebellious cause. The randomization of NPCs plays an important role here also; along with the VK test sometimes proving inconclusive, the questions McCoy can ask and the responses characters give change with every playthrough. As such, players can never predict how a VK test will turn out or what ramification it holds for the narrative. This randomization constantly affects the player’s perception of certain NPCs, instilling that sense of uncertainty the film relied upon. For example, players will be led to believe that the young and defenseless Lucy, the target of so much suspicion, is actually a replicant. Yet in one instance, Lucy may openly volunteer for a VK test, with the results “proving” she is human. In another playthrough, Lucy may refuse to take the VK test and instead tries to escape McCoy’s questioning, forcing him to take drastic action in a scene that pays homage to the film’s Deckard “retiring” the fleeing exotic dancer, Zhora.

You can actually complete the game without retiring a single replicant. Who you kill in the game is a major factor in how other characters treat you, and strongly affects the final outcome. Much like the film however, none of the game’s endings explicitly suggest whether Ray is a replicant or not. Westwood went to extensive lengths to make sure the ambiguity remained intact. Certain important pieces of dialogue with key characters throughout the game were intentionally written to be neutrally interpreted; even the harshest of accusations against McCoy are sometimes met with an indeterminate response.

The experience is not without its problems. There are frantic instances of hunt-the-pixel gameplay, where you have to click absolutely everywhere to avoid missing important items. This is sometimes at a crime scene that you are investigating, which is quite understandable, but at other times McCoy might just be walking down the street. And while the game pays huge respect to the original movie, sometimes it’s just too faithful. Not only are Blade Runner enthusiasts expected to believe that two separate groups of fugitive replicants have stolen and escaped via two separate moonbus’ during the same period of time, but that both these groups use the dilapidated Bradbury Building as a hideout; a hideout which sees both Deckard and McCoy escaping to its rooftops by climbing up dressers to reach openings in the ceiling, naturally. Most curious of all is the appearance of the esteemed cop and enigmatic adviser Gaff. His role in the game is nearly identical to his cinematic counterpart: leading the protagonist with vague statements and leaving behind suggestive miniature paper animals in his abrupt wakes. Which only makes one wonder how he manages to keep an eye on two different Blade Runners and find the time to construct separate sets of ambiguously meaningful origami.

Blade Runner is that rare licensed game that manages to maintain the feel of its source material yet still stand on its own. The various departures from your average adventure game are refreshing, and everything about its production is first rate. Westwood’s Blade Runner may be commercially lost in time but, short of making an analogy involving tears and rain, at least the moments of playing the game will not be forgotten by its vocal fans.