While Image Works is remembered now for publishing action-oriented fare, like Xenon 2 or The First Samurai, the games-centric offshoot of Mirrorsoft sought to capitalize on the growing computer gamer market with a wide variety of genres when the company was first formed. Mirrorsoft had found a great deal of success in publishing computer versions of Tetris early in 1988 – under their own name in Europe and under the “Spectrum Holobyte” label in the US – so it’s little surprise that, when two veteran computer programmers suddenly approached Image Works with a fresh new puzzle game they had whipped up in their spare time, they wasted no time in publishing it.

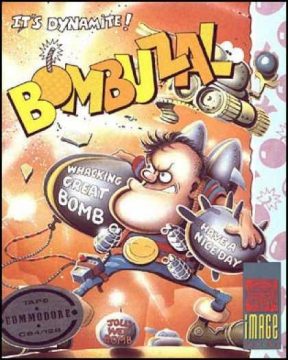

Bombuzal – or Bomb Uzal, as it’s sometimes printed – was one of their first big hits, coming along during that period in the late 80s where puzzle games were in vogue, in part due to their cross-generational appeal. With it’s varied level design and so-ugly-it’s-cute aesthetic, the game was critically acclaimed by a number of publications, including Zzap! and ACE, and was popular enough for Japanese developer Kemco to take notice and make their debut on the Super Famicom with it. Amiga Power went as far as to bundle the full game with their first issue, and wrote about it extensively in their “Issue 0” (a featurette packaged with Amiga Format to hype the then-upcoming magazine).

The game itself was designed by David “Bish” Bishop and programmed by Antony “Ratt” Crowther, two developers who had a great deal of freelance experience with the Commodore 64 in different capacities. Bishop had previously developed Mean Streak, an isometric racing game and one of Mirrorsoft’s early non-edutainment titles, but his work was mostly in PR and advertising for software firms, like Ariolasoft and Domark. Crowther, on the other hand, had a fair bit of fame with Commodore 64 fans as the co-creator of the first Monty Mole game for Gremlin Graphics, as well as heading many of Alligata’s Blagger games. His résumé also includes a number of early Commodore 64 hits, like Killer Watt and LOCO, and his later games were known for pushing the limits of the 8-bit computer in terms of graphics (as in Gryphon) and sound (like with The Suicide Express and its limited use of voice synthesis).

In their spare time, the duo worked on Bombuzal during the production of Fernandez Must Die and Zigzag. It’s even said by Crowther in Amiga Power’s aforementioned write-up how he and Bishop finished production of Fernandez Must Die early to work on this new game full time. This passion project would eventually evolve into an international collaboration of sorts, with other programmers in the U.K., like Jon Ritman and Jeff Minter, contributing levels to Image Works’ newest puzzler. The game, in its initial Commodore 64 form, came out just in time for the 1988 Holiday season. And despite its vintage, some of its more hateful design decisions, and just not being as immediately gripping as Tetris, Bombuzal still is quite a fun game.

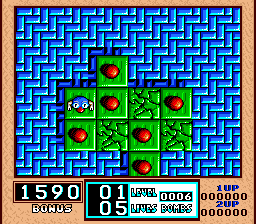

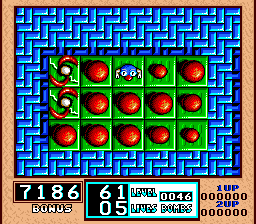

As a logic puzzle game, somewhat in the same vein as Chip’s Challenge or The Adventures of Lolo, Bombuzal has you control a character tasked with setting off all of the bombs on a set of gridded platforms. The challenge lies in having to blow up the bombs without blowing yourself while also leaving yourself enough space to navigate to the other bombs.. This leads to some pretty tricky situations where you’ll have to consider the order and means of how to set off the bombs, as well as where to move the bombs if and when they can be moved. There are also quite a few obstacles to be mindful of, some movement-altering while others simply fatal. You’re also made to solve each level within a time limit, adding a sense of urgency to an already volatile situation.

Bombuzal never saw any official sequels from Image Works or the original creators, but Kemco would borrow many of these elements to produce a spiritual successor. This was The Bombing Islands, a PlayStation puzzle game starring Kid Klown, of Crazy Chase (SNES) and Night Mayor World (NES) fame. This spin-off would be further remixed by Realtime Associates into Charlie Blast’s Territory, with a multiplayer mode and new levels designed by puzzle designer Scott Kim added in. Officially licensed games in its lineage would end there, but Bombuzal was fondly remembered enough to foster a handful of fangames in the early-to-mid 2000s, and The Bombing Islands was enough of a hit to see digital re-release on Japan’s PlayStation Network.

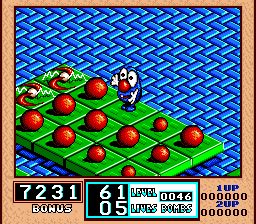

“The whole reason for your existence,” as stated in the Atari ST and Amiga versions of the game’s manual, “is to blow up bombs.” Such is the dreary lot for the nameless, lumpy loaf that is the player avatar in Bombuzal (which looks nothing like the crooked-looking fellow on the computer boxart), but it’s apparently enough motivation to get this one-person bomb squad to face every stage with a grin.

Ambiguous smile and identity aside, your avatar’s purpose is clear: detonate or otherwise eliminate every single explosive on the gridded islands you come across, all without becoming collateral damage. By holding down the trigger button over a bomb, you can prime it to explode, but it won’t until you’ve walked off of it’s space. Once the bomb explodes, it will set off any other explosives within and adjacent to the blast. How big the blast depends on how big the bomb is, and typically only the smallest of bombs are safe to detonate manually.

Blowing up all of the bombs on a level will require an intimate knowledge of how each of the hazards and obstacles in a certain stage interact with each other. Aside from the aforementioned bombs, there are occasionally mines that also need to be destroyed, which are lethal when stepped on but will not set off any bombs adjacent to their explosion. There are also antenna bombs, or “A-Bombs,” which blow up all other A-Bombs when one is blown up. Tile-based hazards, like the slippery Ice Tile or the brittle Dissolver Tile, make navigating to each of the bombs more of a challenge, and hostile characters Sinister and Dexter will occasionally appear as moving – but strictly patterned – instant-death hazards.

Bombuzal is all about carefully considering the different elements of each level and, within a sometimes unreasonable time limit, coming up with a way to navigate through these elements to fulfill your incendiary task. Sometimes, you’ll have to navigate a maze of mines, teleporters, or both to set off the right bomb and trigger a chain of explosions. Sometimes, you’ll need to blow up a mine by using one of the two remote-controlled robots in the game to step on it for you. Other times, you may find yourself carefully considering a path through a field of ice tiles, working out how best to navigate the stage without slipping off the edge.

On paper, Bombuzal has all the elements of a deeply engaging puzzle game, with a variety of different hazards to keep things from becoming too repetitive. And, at least within the first 30 or so levels, the game is quite engaging. Some of the levels, even this early in the game, will require a bit of trial-and-error to fully understand, but once you’ve finally pieced together what it is the level designers expect from you, and you set off that final bomb to finish the level in a beautiful cascade of explosions, the feeling is sublime.

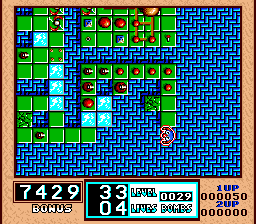

But the levels get larger, more complex, and more than a little cruel. Soon, the limits of your scope of view become apparent in these larger stages. Playing the game in 2D Mode allows for the best view of the surrounding tiles, but this is hamstrung by the fact that the camera doesn’t move until you’re a single tile away from the edge of the screen. This makes the threat of accidentally walking into a moving enemy or a mine ever present, and not at all fair. There’s also a 3D mode to play in, but the isometric viewpoint shows even less of the level, with all of the graphics and sprites redrawn in a larger, more cartoony style, and it introduces another frustration: controls. Until you’ve made yourself comfortable with which direction the game registers as up, down, right, and left, you’ll be prone to slipping off of edges and having to restart levels because of slight missteps.

The Map mode, which shows a zoomed-out overhead view, is supposed to alleviate with some of these woes, but the levels soon become too large for the map to accommodate, and not being able to show the entirety of the stage leads to some really sketchy blind leaps of faith into unknown territory, especially when teleporters are concerned; you may be suddenly whisked to the other side of a large stage, and not know where you are in relation to where you just were. This makes planning for stages ahead of time difficult, and sometimes knowing just what the stage wants you to do will require a few deaths on your part. The game operates on a lives system, but getting a Game Over never poses that much of a threat. The reason for this is twofold: you get an extra life with every level you complete, and the Continue option on the title screen will send you back to the stage you were working on.

Unfortunately, dying is its own major inconvenience, primarily in the larger levels that require a few minutes to get through. Some of the levels are particularly nasty, in that you will have no reason to believe you’ve screwed up a level until near the very end, when you’ve forgotten to blow up a single bomb or find yourself being teleported off into the abyss below because you’ve destroyed the wrong unmarked tile. Most times, these screw-ups are genuinely the fault of the player, but having to redo 2 or 3 minutes of set up because of it is no less frustrating. A rewind system, or some way to go back a few actions, would’ve been nice.

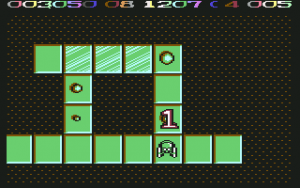

Getting a game over gives a 4-letter password and the ability to continue from the stage you left off from the title screen. But, at least in most of the original computer versions, the game only gives you a new password every 4 to 8 stages, making resuming a game at a later time potentially troublesome. The game initially came out for the Commodore 64 in December 1988. While this version is arguably the ugliest of the different versions, with garish color palettes and squished overhead tiles that are occasionally hard to decipher (especially in Map mode), it runs at a good speed and actually plays a little better than the later ports, if only because the screen actually keeps you centered in 2D mode. The sound design is also impressive, with a catchy intro tune (composed by Crowther), and a voice clip announcing “Get Ready” at the beginning of every stage.

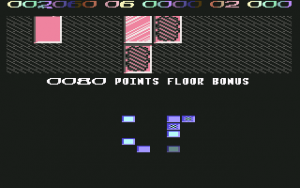

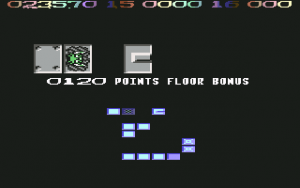

The game would get ports to the Amiga and the Atari ST the following month, which were handled by Ross Goodley. These two are identical in terms of graphics and presentation, but the ST version’s sounds and voice samples come out tinnier due to the inferior sound hardware. On the other hand, the Amiga version isn’t emulated very well on most Amiga emulators, with the sound effects only working intermittently for whatever reason. Both versions run slower than the Commodore 64 version, though, and generally sound much worse.

The 16-bit versions do have a cleaner, though somewhat bland, look to them, with new graphics and tile designs done by Crowther that better convey what their purpose is. The enemy characters, Dexter and Sinister, have lost some of their abstract oddness, going from looking like a small black hole and a spinning triangle respectively to an orb and… several orbs. Additionally, the colored tiles floating above the unchanging blue patterned abyss looks less visually interesting than the vibrant, though odd color pairings in the Commodore 64 version.

Presentation complaints aside, the extra customization options are nice. You can now use the keyboard or a mouse to control your character, in addition to a joystick, and you can remap the controls to your liking. There’s also an alternating 2-player mode, you can use the keyboard to type in passwords for once, and there’s the ability to switch between 2D and 3D modes on the fly. These versions also boast a staggering 250 levels, but the game starts repeating levels at around 136, and not having room for three numbers in the level counter can make things confusing when you notice Level 99 suddenly looping around to Level 00.

There was also a DOS version, ported over by Tony Love, which looks like a less colorful version of the 16-bit computer ports for the most part. There’s no music or voice samples, and the sound effects come straight from the PC speaker. The primitive sound hardware doesn’t sound terrible, but the crackly static used for the explosions don’t quite convey the same level of “oomph” as the other versions. Still, the game runs at a respectable speed, faster than the Atari ST version but a little slower than the Amiga.

The DOS, Amiga, and Atari ST versions were initially only released in the U.K. and in certain parts of Europe, though the game did eventually make its way stateside in the 90s. Aside from the to-be-mentioned SNES port, Cinemaware (another offshoot of Mirrorsoft) bundled Bombuzal with Xenon 2 for the Action Pak: BrainBlaster bundle, to little fanfare. Given that Cinemaware was then known mostly for movie-like games heavy on narrative and presentation, it’s no surprise the oddly cutesy-looking puzzle game didn’t garner the same attention in the U.S. as it did in Europe.

Yet, despite its British nature, the game never received ZX Spectrum or Amstrad CPC ports. The game was supposedly slated to make an appearance on these computers, as hinted at in various publications at the time. The original creators have not stated anything to the effect of there ever having been such ports in development, however.

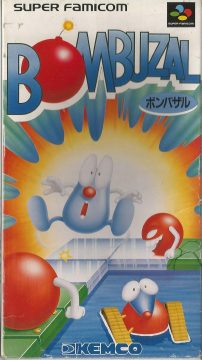

In August 1990, at the Nintendo Shoshinkai hardware demonstration, Kemco unveiled their own conversion of Bombuzal for the then-unreleased Super Famicom, along with a conversion of Infogrames’ Drakkhen. Drakkhen, perhaps due to being more mechanically dense, wouldn’t be released for nearly another year, but Bombuzal would end up as the very first third-party title released for the Super Famicom, hitting store shelves in December.

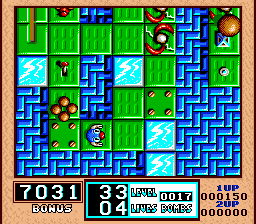

Visually, it borrows a lot from the 16-bit computer ports, though it moves the interface elements to the bottom and stretches the screen a bit vertically to accommodate the system’s greater vertical resolution; most noticeable is how much taller and leaner the player’s avatar seems to have gotten in this version. The title screen music is also a recomposed version of Goodley’s title screen theme for the Amiga version, using early SNES instrument samples that make the game sound a lot like Kemco’s later ports of Drakkhen and Lagoon.

This version of the game feels much more accessible than the 16-bit computer ports. Passwords are given at the start of every stage, with most of them taken from the DOS version. As both feature the same 130 level count, this is not entirely surprising, though now every level has its own password. Pausing the game not only shows you the map for the level, but it pauses the timer as well, allowing you to carefully plan out your movements before screwing yourself over. These things make for a less frantic, but more bearable, game.

Super Famicom Bombuzal is much more musical than its computer counterparts, though whether Hiroyuki Masuno’s compositions add anything to the experience is highly debatable. His work on Kemco’s earlier Famicom games, including The Bugs Bunny Crazy Castle and their ICOM adventure game ports, worked well in their respective games, but his first work with the Super Famicom’s SPC700 sounds more like a dry run with the sample-based hardware. Kemco must’ve also been very proud of their badly pronounced “Get Ready” voice clip, because not only is it used to begin each stage, its sampled throughout the game’s one and only stage theme. Needless to say, the music can get grating rather quickly.

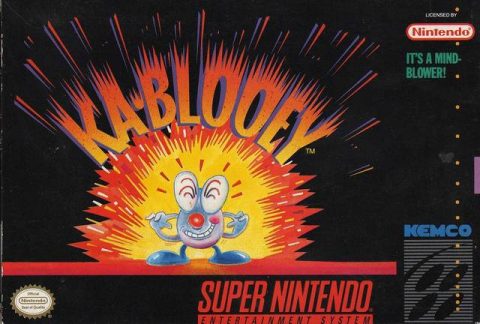

This version would never see release in its native Europe strangely enough, but it was reworked into a later, yet inferior, American release. Released in 1992 and rebranded as Ka-blooey, this version features a completely overhauled soundtrack, with improved instrument and voice samples, as well as a retouched title screen. Kemco also saw fit to remove the 2D mode entirely, as well as change up the passwords ever-so-slightly so that the SNES passwords are not compatible with the SFC version. The levels themselves are unchanged, and the game is playable once you’ve gotten used to playing in 3D, but no one in America seemed to care at the time.

Lemon64’s Entry on Bombuzal

Chris Covell’s scans of Marukatsu Famicom’s coverage of the August 28th & 29th public unveiling of the final version of the Super Famicom and games, including Bombuzal.

The AMIGA Magazine RACK. Lots of Amiga-related magazine scans here, including Bombuzal reviews and interviews.

Bombzuka – Windows (2006)

Developed by programmer and game designer Matt Pilz, this remake was designed as an entry for Retro Remakes’ 2006 competition, where freelance developers from all over gathered to develop remakes of old games. The theme for this particular competition was “accessibility,” or more precisely “good remakes of good games that anyone can play, regardless of their ability.” While Bombzuka only made it as far as eighth place, the remake still stands as technically one of the best ports of Bombuzal ever made.

The game combines features from the 16-bit ports of Bombuzal, including a title screen and options screen that heavily resemble that of the Amiga and Atari ST ports. Also present from those ports are the different and adjustable control setups. So, if you prefer controlling Bombuzal with a mouse for whatever reason, this remake’s still got you covered. There are also clickable action buttons at the bottom of the screen, allowing for those who aren’t able to use a conventional controller or the keyboard to control the action with mouse clicks. And, as with the 16-bit computer ports, controls are remappable.

Bombzuka also borrows a few elements from Kemco’s version. Each level has its own password, given to you at the beginning of the level. There’s background music to accompany the gameplay, though this time you can turn it off if you’d rather play without it. The game also features the original 130 level count of the SNES, DOS, and C64 versions, though a few levels have been tweaked very slightly to make the some of the puzzles less reliant on guesswork and precise execution. The passwords are completely different here than in any other version, but since the game auto-saves your progress, there’s hardly any reason to use it. And, as with Kemco’s version, bringing up the map pauses the timer.

Additionally, the difficulty level can be changed, though not by means of a difficulty slider or anything like that. Rather, you can adjust the speed of the timer, as well as toggle lives. While the instruction manual warns that doing so will significantly reduce, and in some cases disable, your scoring capabilities, it does allow for those not comfortable with the demanding nature of the original game a little more leeway.

Though the game plays just as well as it ever has, the game does look a little ugly, and the sound design is arguably worse. On the other hand, the game was coded and developed within the span of 3 months, and for what we would probably consider a Game Jam nowadays, so the amateurish look of the game is excusable, and admittedly somewhat charming. Presentation issues aside, this is just about the best port of the classic Bombuzal out there, fixing many of the frustrations of the original versions while maintaining the clever puzzle aspects.

Links

Article about Antony “Ratt” Crowther’s contribution to the Commodore 64

An Informative Article Sample on the Formation of Image Works (and the origins of Bombuzal)

Archive of an article on Mirrorsoft in an old issue of CRASH Magazine

Homepage of Matt Pilz, creator of the Bombzuka remake. Has a download link for the game in the “Portfolio” section, but the version on that site has a game-killing bug where the enemies’ hitboxes are too large.

Retro Remakes Competition Entry Archive. Has a more playable version of Bombzuka in the “2006 Entries” section.