Sega’s 1985 arcade game Space Harrier broke ground for 3D shooters, and is natural for these type of things, spawned a number of imitators. (The Japanese term for these is “Supehari-kei”, or “Space Harrier-type”.) Namco’s Burning Forceis among the better of these clones, partly because it’s based on more powerful arcade hardware (the Namco System-II, which ran Phelios and Valkyrie no Densetsu, amongst others), and partly because it puts its own unique spin on the formula.

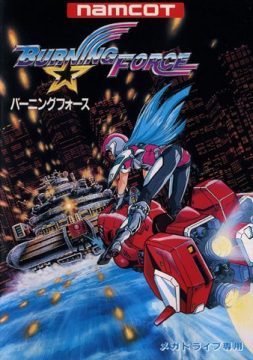

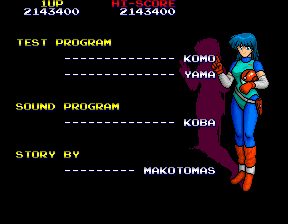

The star of Burning Force is Hiromi Tengenji, a 21-year old cadet at Earth University, taking her test to graduate and ascend to the tank of Space Fighter. Her test takes place over the course of six days, as she rides her transforming airbike, the Sign Duck (MSRP: $41,100 in year 2100 dollars, according to the supplementary material) over oceans, deserts, forests, and finally into outer space.

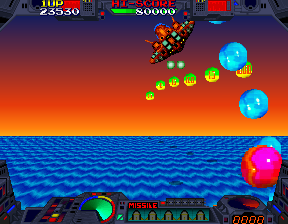

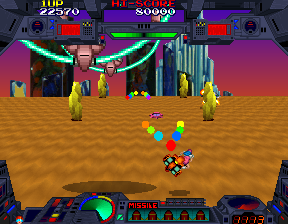

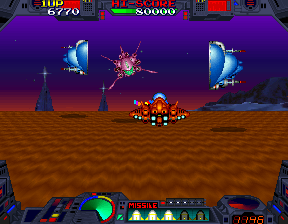

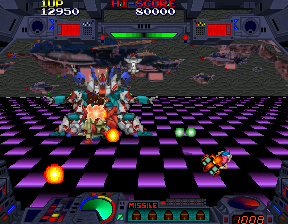

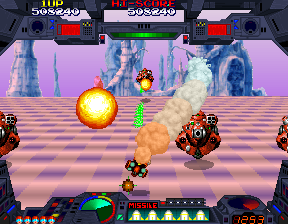

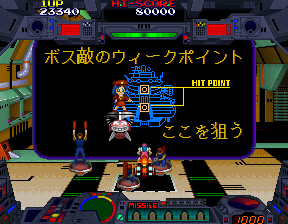

Each day is its own stage, and most are broken down in four sections, taking places at different times of day – beginning from daytime, moving to night, then eventually back to dawn. The first two are played on the airbike, each culminating in a miniboss fight; for the third, the airbike transforms into a jet fighter and ends with a fight against a larger boss; and the fourth, continuing as the jet fighter, is bonus stage where you try to pick up as many orbs as possible for points. Right before the beginning of the third section, you are given a briefing by your instructor, Miss Kyoko, who points out the boss’ weakpoints. The final day is only one section long, and occurs entirely in jet form.

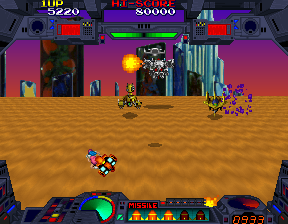

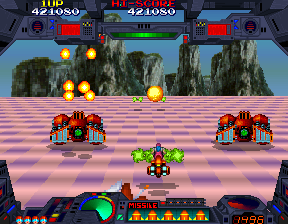

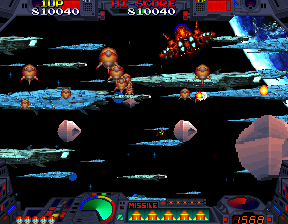

Still, over half the game is played on the airbike and this is where the game primarily differentiates from Space Harrier. Since it’s bound to the ground by that pesky thing called gravity, you can only move left and right, while pressing up or down is used for changing speed. Tactically, this means it’s much harder to dodge enemy fire, since you can’t just fly over it. The enemy patterns, formations, and projectile types are also more complicated, especially the rockets which explodes on the ground in eight directions, which requires some deft speed manipulation (or, better still, destroying said rockets before they detonate) unless you want to be killed.

There are several speed ramps found throughout, and hitting them at the right speed will send you into the air, which usually hold a variety of power-ups. In addition to the standard projectiles, you can also equip yourself with lasers, wide range shots, and the slightly more powerful cross lasers. You also have a limited amount of missiles, in two varieties – homing missiles and “max” missiles, which are shot in front of you and explode outwards. A single hit will destroy your airbike, although you can bump into most objects harmlessly, which merely slows you down, but does temporarily render you vulnerable to follow-up attacks.

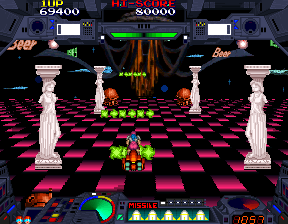

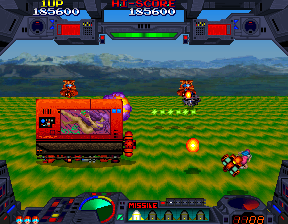

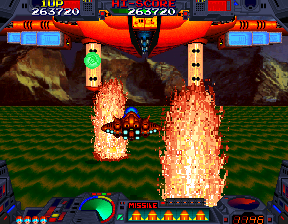

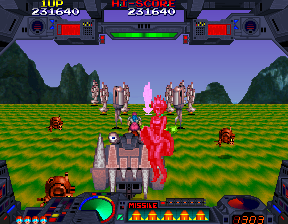

The visuals are nicer than Space Harrier, naturally due to the game being developed five years afterwards on substantially more powerful hardware, though not nearly on the level of Galaxy Force, Sega’s own super scaler follow-up. The enemies are largely mechanical in design, ranging from planes to mechas to boats, so its design really isn’t as inspired as Space Harrier or some of its goofier clones. That being said, the third stage, Aero Space, is the most impressive part of the game, with a flashy checkerboard pattern and Greek statues that, along with the dated-yet-hip 80s pop music, suggest some kind of mythological time-traveling dance club. Other weird bits include the trucks which seem to have nude ladies painted on the side (it’s hard to see since you zoom past them so quickly) and the boosters which seem to have a hologram of a Marylyn Monroe-type, holding her skirt down from the upwind breeze.

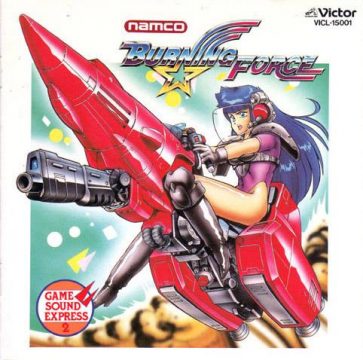

The soundtrack, provided by Yoshinori Kawamoto, is fantastic, with the first level “Bay Yard” sound easily ranking up next to the theme from “Valkyrie no Densetsu” as one of the best composed by classic Namco. Each stage has two themes, with the second being a slight “night time” variation.

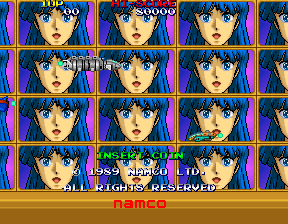

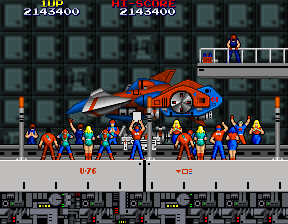

It is a little unusual that Namco put such emphasis on having a cute heroine, at least on the title screen and in promotional material, but since the game is viewed from behind while she’s on the jetbike (or completely hidden when transformed into a jet), that in most of the time she’s just a blue-haired, pink-clad blob of pixels. It’s hard to get much of a sense of her character in her, at least compared to Namco’s other popular heroine (and probable inspiration), Wonder Momo. Her most impressive moves are when the airbike is destroyed, as she gymnastically somersaults into the hair and lands unharmed on the replacement jetbike that appears beneath her (assuming you have extra lives, anyway.)

Even though the lack of maneuverability, combined with the occasionally overwhelming enemy onslaughts, can make those three-lives-per-credit disappear relatively quickly, Burning Force is nonetheless a great game, certainly worthy of stepping outside of the shadow of the game that clearly inspired it.

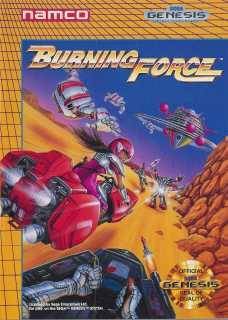

Burning Force‘s only port to systems of the era was to the Genesis, in 1990. The effect of the scrolling landscape has been replicated almost perfectly, but the scaling of the enemies is, of course, somewhat choppy. Unfortunately, its speed and smoothness is part of what makes the arcade game so impressive, so its technical deficiencies do reduce its enjoyment. During most of the game it’s alright, but the boss battles really take a hit, since they were the most impressively designed sections of the arcade game, heavily relying on scaling and rotation effects. In the arcade version, the fourth level boss, a gigantic space cruiser, zooms in from beyond, showering electric bolts and chucking bombs from above. Such impressive effects are largely absent from the Genesis release.

Some of the landscape elements are gone, like the archways you could previously fly through, or the neon signs that appear in the third stage. The levels don’t seem as fast-paced, and parts feel relatively empty by comparison. More annoyingly, in the arcade version, the background image changed with the time of day to completely new images. Here, the same image is used throughout the stage, just changing the color palette, which makes the levels feel more repetitive. The music hasn’t really survived the transition either, with much of the soundtrack converted into harsh mechanical noises, even though the melodies are still mostly the same.

The port is also substantially easier, both due to the lesser amount of enemies, and the fact that you can take three hits before getting destroyed instead of one. Additionally, destroying background elements can occasionally yield green orbs. Grab five of these and you can activate a brief period of invincibility, any time you want. It’s not a bad change, considering the arcade game could be unfairly difficult and overwhelming in spots. Taken all together, it’s certainly a better conversion than Sega’s own Space Harrier II.

There’s also a strange change in the ending. In the arcade version, as a reward for graduation, Hiromi is given a piece of headgear that looks like a tiara. In the Genesis version, this was changed to a military-type hat, which really makes more sense. She’s in a combat academy, after all, training to be a Space Fighter, not a Space Princess.

Despite the numerous compilations that Namco had released over the years, Burning Force had remained largely ignored. The only other time it was officially released was as a part of the Wii Virtual Console in 2009 (only in Japan, sadly), which is an arcade-perfect port.

Hiromi had not been entirely forgotten though – she appears as a playable character in the Japan-only PS2 strategy fan service game Namco x Capcom, teamed up with Toby Masuyo, the heroine of Baraduke. Of course, she rides the Sign Duck. They are both noted to be members of the G.S.F., so both games appear to be part of the same continuity. There is also a Burning Force music medley that appears in assorted Taiko no Tatsujin titles.