In the early 1950s, a progressive political leader named Mohammad Mosaddegh was democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran. His administration’s main policies were the introduction of social security, the enactment of land reforms, and a bold move to nationalize the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The latter didn’t please the United Kingdom.

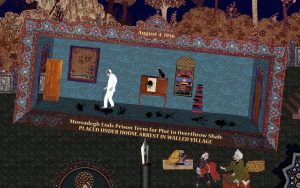

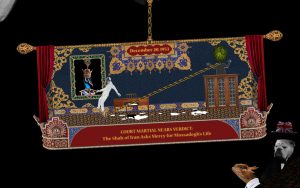

So the British government had the MI6 team up with American intelligence in a bid to secretly overthrow Mosaddegh. The bloody coup, nicknamed “Operation Ajax” by the CIA, achieved its goal – Mosaddegh was deposed then held under house arrest until his death, and the pro-Western monarch assumed autocratic powers. It was the first move of its type during the Cold War, but sadly far from the last.

If you’d like to learn more and even feel more about this event, you should definitely give a try to a documentary game titled The Cat and the Coup, the brainchild of two creators from the Game Innovation Lab of the University of South California, a division dedicated to experimental game design from which Jenova Chen (of Journey fame) also graduated.

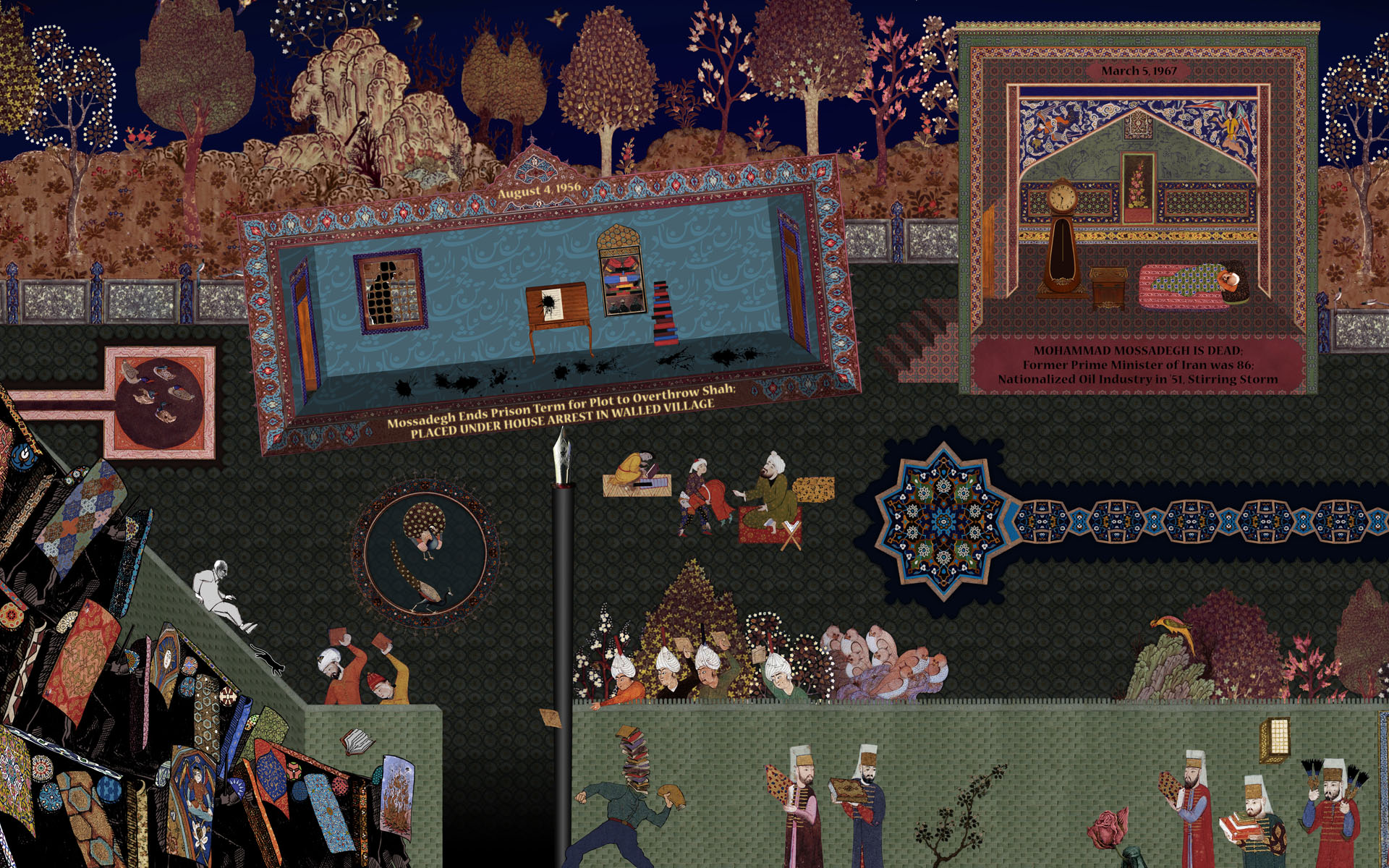

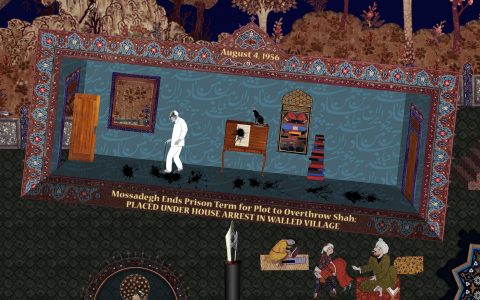

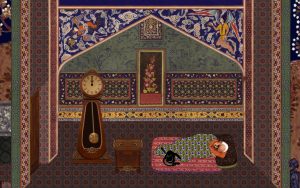

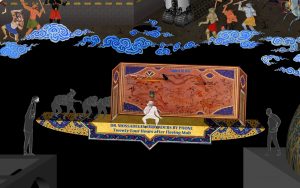

The game puts you in control of an imaginary, innocent-looking black cat running along Mosaddegh in a series of Persian-inspired tableaux with surreal twists, which all represent specific stages in the man’s later life. Progress is made by solving simple puzzles that often involve knocking stuff down and messing with the room’s balance through feline meddling. Every time a riddle is solved, the haunting story unfolds and leads the Prime Minister closer to his inevitable downfall.

What makes the game a breakthrough as a genuine documentary game is the fact that the player, while engaged in actual puzzle-solving, is not capable of influencing the course of history. Though you do take symbolic action, it cannot achieve anything more than letting events take their own course. It’s as if the player, both an active agent and helpless witness, assumed the role of History itself. Playing and learning thus become closely intertwined.

Sure, the experimentation is not without its flaws: the collision detection is a bit murky, the visuals though very inventive are a bit uneven and the closing song is a curious pick; but this shouldn’t refrain you from putting your hands on the game. Even though it lasts no more than ten minutes or so, The Cat and the Coup remains both a unique and historically enlightening experience that sets a precedent in the seamless fusion of education and entertainment.

By the way, if you’re interested in a behind-the-scenes look into the game, do check out the following interview.

Interview (with Peter Brinson):

How did you end up working on The Cat and the Coup? Was working on an interactive project something you always wanted to do, or a more recent subject of interest?

► Back in 2007, I wanted to make a war-themed game that wasn’t like the others. Video game history is replete with war-themed games that were released at a time when the United States were themselves at war (in Iraq and Afghanistan). And politicians were talking about being aggressive with Iran (and still are). So I wanted to make a project that cast light on an ongoing type of warfare – the various coups of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The game’s mechanics are no gimmick; it really works organically with the narration. Was it hard to design? What inspired you to create such mechanics?

► I wanted mechanics that provided indirect control. As a seemingly ineffectual cat, you were manipulating Mosaddegh’s world so that he would make bad decisions. This is how the CIA operates. It was a hard game to design because the story, mechanics, and art were interdependent. Each change had a ripple effect.

The game’s distinctive visuals are a mix of middle-eastern traditional art and satirical collages a la Monty Python. How did you come up with that art direction?

► The art director and my co-creator Kurosh ValaNejad directly referenced Persian miniatures, a style and period of drawing from roughly the 13th to 16th century. The style lacks contemporary forms of perspective (like seeing depth) and instead has its own take on representing space. He felt it would be a nice take on a 2D game. About half-way through production, people started to make the Monty Python comparison, which is a great compliment.

The game doesn’t merely state historical facts; it also clearly takes a critical stance towards Western imperialism. Do you think games can make a political impact?

► Video games are natural at making the player feel responsible for their actions. And if their actions are those of the CIA, then the player feels a sense of ownership about consequences.

Do you feel documentary games have a distinctive quality that set them apart from “usual” documentaries? In your opinion, is there something that only interactivity can convey?

► Games are learning systems. If the player doesn’t learn what buttons to press or that keys open doors, for instance, the experience fails. Therefore, games can do more; they are a great format for learning about and exploring topics.

What do you think about the line that is generally drawn between “serious games” and “traditional games”? Do you think of The Cat and the Coup as a “serious game”?

► Labels are a starting point for discussion and so the term “serious game” is fine for that. What we discuss though is the goal and the point.

Links:

The Cat and the Coup on Steam Where you can get the game, for free.

Official Website The game’s page, which also offers download links (including a Mac version).

Game Innovation Lab The USC School of Cinematic Arts initiative’s web portal.