It’s difficult to approach discussing Catherine, Atlus’ PS3/X360 narrative-focused puzzle game, without also discussing the Persona series. Despite the lack of gameplay and narrative ties with Persona, Catherine is inexorably tied up with Atlus’ flagship franchise. There are the obvious connections: many of the creative minds behind the Persona (artist Shigenori Soejima, composer Shoji Meguro, designer Katsura Hashino) worked on the game, and many of the motifs they’d developed in their previous work made it into Catherine. Hashino remarked the game, being their first time working in HD, served as a sort of test site for how they would later develop Persona 5 (although that’s as far as the connection goes). The developers even used Yukiko Amagi to test/show off some of the gameplay features, and Vincent makes a cameo appearance in the PlayStation Portable version of Persona 3 ahead of the actual game he starred in.

Of course, there are also some important distinctions between the two works. They have vastly different play styles, with Persona being a mix of a life/dating sim, and Catherine being a puzzle game with a strong accompanying narrative, comparative to a visual novel. Hashino and others saw Catherine as an opportunity to explore subject matter a high school setting wouldn’t allow, like adult life and extramarital affairs. Ultimately, the game’s position of simultaneously existing both outside Persona and within it has come to be its most defining feature.

Yet at least in the beginning, Catherine‘s appeal was meant to derive from its narrative. This was where the team’s efforts were their most concentrated: the narrative premise formed the core around which the rest of the game was built, and the abundance of anime cutscenes produced by Studio 4°C to convey that narrative.

Initially, the premise appears very simple. After blacking out after a night of drinking and finding out that he’s cheated on his fiance, the main character, Vincent, must spend the rest of the story covering his tracks and making sure this affair ends before things get out of control. Unfortunately, things only get worse for him as time moves forward and he continues to cheat on his future wife.

Characters

Vincent Brooks

The protagonist of Catherine, Vincent Brooks has very few if any redeeming qualities. He’s an unambitious, insecure, passive person who lets other people make decisions for him, is absolutely terrified of the two women in his life, and gives into his own weaknesses all too easily. He’s also a consummate liar (even when he has no reason to lie and doing so would be to his disadvantage) and spends all his free time drinking with his buddies. Despite all these flaws, the game ultimately presents Vincent as a sympathetic figure.

It should be noted that in his dreams, Vincent is more assertive and determined than his real life counterpart. Unfortunately, because Vincent can never remember the contents of those dreams, this improvement proves little comfort for him.

Katherine McBride

Katherine McBride is a stark contrast to her fiance Vincent. Where her boyfriend can’t get his life together, Katherine is more ambitious and career driven; always thinking about the future. It’s enough to make you wonder what exactly she sees in Vincent.

This question the game never adequately answers. There is some backstory about how they met, but all it does is reinforce Vincent’s flaws while introducing new ones. Instead, Catherinereinterprets Katherine’s personality so she’s just as flawed as her fiance if not moreso. Her ambition comes across either as an impersonal, almost business-like desire for control or as an inexplicable force of anger and reprimand for Vincent to deal with.

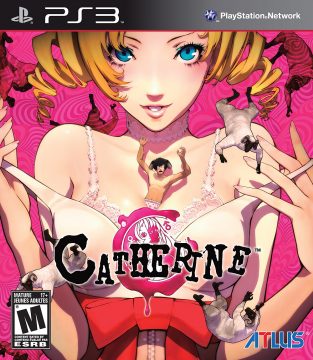

Catherine

Vincent’s paramour and the main force of conflict throughout the game. Throughout most of the story, not much is known about her; not even her last name. The most immediate aspect of Catherine’s character is how strongly the game sexualizes her, whether it’s all the sexually charged camera shots or the fact that several in-game days pass before Catherine is seen wearing clothes. Despite being in her early twenties, she consistently acts childish, cheering and laughing when things go her way or acting like a hedonistic selfish brat who wants to keep Vincent all to herself.

In addition, there’s a cornucopia of personalities Vincent interacts with when drinking at The Stray Sheep (a local bar). There are too many to list, but to summarize the characters most important to the plot:

Orlando Haddick

The first member of Vincent’s group of four and perhaps his closest friend, judging by how often the two spend time together alone. Orlando comes across as the suave, cool lady’s man every guy wants to be. However, his past directly contradicts that image: he married young, but after falling for a scam and running his business into the ground, his wife divorced him.

Jonny Ariga

Another long time friend of Vincent’s. If Orlando is cool in the sense that he gets along well with other people, then Jonny is cool in the sense that he doesn’t express his emotions all that much. He’s quiet, collected, and is probably enjoys the most success in life out of any of the four guys.

Toby Nebbens

The youngest member of the group, both in terms of age and because he’s the most recent member (not having grown up with the other three). Toby’s personality is the polar opposite of Jonny’s: energetic, enthusiastic, and all around youthful. Toby also has a crush on Erica, something the other three guys discourage him from pursuing.

The Boss

Owner of The Stray Sheep. He’s the kind of person who could easily be a suave lady’s man if he had any interest, but who most likely put those days behind him long ago. Nowadays he’s content on giving Vincent advice on navigating his life.

Erica Anderson

A waitress at The Stray Sheep and good friends with Vincent’s gang. Erica is depicted as a somewhat assertive woman, but significantly friendlier in contrast to Katherine. She’s also a fan of women’s pro wrestling. An offhand comment in one of the game’s endings reveals Erica is transgender. Catherine‘s clusmy handling of this fact has been the subject of much criticism ever since the game’s release.

Based on these descriptions, one could reasonably read Catherine as a repudiation of Persona‘s themes. The problems the characters have to deal with are often the mundane results of adult life, like managing a healthy relationship or thinking about how to advance one’s career. Should the characters find themselves in a more exciting problem (i.e. Vincent’s adultery), any feelings of excitement are clouded out by helplessness and disempowerment.

Yet disempowerment aside, these differences don’t go much deeper than the surface. Catherine isn’t concerned with extramarital affairs as an end in themselves, but because of the larger issues they allow the writers to explore. Moreover, those issues they explore find precedent in the team’s earlier works. Where Persona 3 deals with the struggle of relating to others and Persona 4 explores people’s tendency to flee from their own individuality, Catherine weaves both threads into its own thematic tapestry.

One of the main themes of Catherine is “lack of individuality”. Nobody wants to face themselves and everybody’s looking for any opportunity they can to avoid doing so. The modern world they live in provides many such opportunities. One can always lose themselves in the comfort of the daily grind. Likewise, the bar scene provides Vincent and his crew a chance to distract themselves from the Other by retreating into a world of the self where one need never think about the nothingness clawing away at them from within. Even the act of Othering is portrayed as a comfort in Catherine. Because the characters are so caught up in such an extroverted act, none of them stop to realize that they’re the ones reading the Other as a threat, let alone the deeper reasons that drive them to do so in the first place.

There are three key areas in Catherine where these topics manifest:

Nightmares

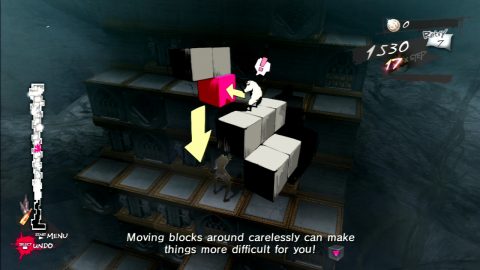

According to some local rumors, men who have been cheating on their romantic partners are cursed with a specific kind of nightmare. These men find themselves in a mysterious world with stacks of blocks, while wearing nothing but their boxers. They have to climb to the top of this world, which is slowly collapsing, and reach the Cathedral, lest they risk dying (in the real world) of mysterious causes.

Each level asks players to guide Vincent to the top of a tower made of blocks. In almost all cases, this is done by pulling blocks out so they serve as a suitable staircase to reach the next level. It’s an elegant premise that would feel right at home in an 8-bit game: simple enough to understand from the start while also allowing a lot of room to expand. Though most blocks can be pushed or pulled, some cannot be moved at all, others will crumble after staying on them, some are slippery and will send you careening in a direction until you reach one that isn’t, some are timed bombs which will destroy everything around out, and some will kill you instantly. And so forth.

There are a few main things to remember, particularly the game’s strange rules of gravity. Blocks will remain suspended as long as they’re attached to another block around its edges, essentially allowing them to float in mid-air…unless you push out everything around it, of course. You can also drop off, hold onto, and move along the edges. You can push multiple boxes in a row at once but can only pull them one at a time. The tower is also three dimensional, in that there are extra columns of blocks behind the main ones, though since the blocks are opaque it’s hard to actually see them. You can tilt the camera but this only makes the edges visible, so many still remain obscured.

You’re scored on several factors, including how fast you complete the stage, how many stashes of gold you manage to grab, and how many combos you create (every move upward adds to the meter and staying on that level or moving downwards for too long will reset it). Between levels, you use this score as currency to buy single use items to help you out, including blocks that you can create at any time or drinks that allow you to climb multiple blocks at once.

Vincent isn’t the only one in this world, though, and there are several other competing sheep climbing the same block towers as you. They aren’t friendly though, and can easily bump you off or otherwise get in your way, so it’s push or be pushed. At the end of every major level, there’s also a boss “fight”, consisting of creatures based off Vincent’s anxities, including a large monster with a butt for a face, evil babies, and various incarnations of his fiance. There’s no way to attack these things, of course, so you just have to climb faster and dodge their attacks.

Death is, of course, fairly common – fall off the tower and you’ll fall helplessly to the ground and splatter on the ground, accompanied with dramatic music and the famed phrase “LOVE IS OVER”. The game is fairly generous with failure though, as you get a large number of lives to start off, there are regular checkpoints, and you can undo your moves by hitting the Select button (though while Vincent’s moves may be reversed, it doesn’t hit rewind on the collapsing of the tower, so you can’t abuse it regularly.)

It can be quite hard, especially at the beginning, where you’re still learning its various eccentricities. There have been dozens of block-pushing games in the video game canon, ranging from the likes of Sokoban and The Adventures of Lolo, but none quite like this one. When the game was initially released in Japan, the audience critized it for being too difficult, causing Atlus to respond with a patch that made it a bit easier. The overseas versions include these enhancements built-in, which is welcome, particularly because the “undo” option was originally only in the Easy mode.

The idea behind these puzzle segments was most likely to illustrate the reality Vincent feels he has to face; each level sees Vincent performing menial work to earn money in a desperate bid to stave off death. But strangely enough, those design decisions are also what has made the game attractive to play in its own right. Where Catherine sees the individualistic struggle to survive as desperate for most of the game, its players, spurred on by level design that encourages a multitude of strategies and a scoring system that rewards quick thinking, have succeeded in finding their own value in play. It also helps that the levels encourage multiple approaches to the same problem. Their design is rigid enough to allow for a definite solution, but also flexible to allow whatever the level designer didn’t account for, even if it contradicts the premise of the game (e.g. lowering the top of the tower to you rather than climbing straight to the top). Combine all of these elements, and you get a community of speedrunners competing for the best times even years after the game was first released.

From a pure gameplay perspective, these nightmares are what the game uses to present the block puzzle gameplay. But from a narrative perspective, this is where Catherine most clearly shows its Persona influences, and where the two stories most diverge. The parallels between Vincent’s nightmares and something like the Midnight Channel should be obvious to fans of Atlus: for some this otherworldly realm is a rumor, but for others, it’s all too real. Dense with symbolism on multiple levels (religious, sexual, social/economic, poetic), the dream world lays bare the logic of Vincent’s life, forcing him to confront the personal issues he would rather run away from.

But if Persona empowers its protagonists with powers just as fantastic as the worlds they navigate, then Catherine disempowers its cast with crushing reality. (It helps that what Vincent sees in his nightmares never quite stays in his nightmares. It’s unsteady, always threatening to leak out into the real world just a little bit.) Judging the situation as a player, there’s very little hope that Vincent or any of the other sheep in his nightmare will ever learn their lesson. They interpret others as sheep because they want to think of themselves as the only true individuals, unaware that this is how all the other sheep see the world. None of them confront their own aimlessness or think that other people can provide a solution; their focus on survival is too provincial to allow that. All are in need of guidance but few are willing to accept it.

Judging the situation from their perspective, that focus is well justified. Stripped to nothing but their underwear and stripped of any means of fighting back, their experience in this world is marked by vulnerability, embarrassment, and a constant fear of death. That fear forces them to accept whatever salvation is offered to them. Enter the confessional. Here, Vincent is posed an open-ended question and made to choose between one of two choices, which generally revolve around relationships (first Q: is marriage the beginning of one’s life or the end?) Each one is tied to the game’s morality system, which partially determines what ending the player gets. It can be understood as vaguely evocative of Shin Megami Tensei as funneled through the later Telltale games like The Walking Dead. It will even connect to the internet to give you an idea of how many players picked similar (or differing) responses.

Incidentally, there’s also an arcade game-within-a-game called Rapunzel, which is exactly like the core game but presented with old school (though still 3D aesthetics). Though there’s no time limit, the puzzles themselves are actually much harder, so it’s a more “classic” take on the core mechanics of the game.

Socialization at The Stray Sheep

Compared to the events in his nightmares, Vincent’s time at the Stray Sheep is significantly more relaxing. Here, Vincent can talk to his friends; have a drink or three; play some Rapunzel, an arcade game modeled after the Nightmare stages but with a slightly modified ruleset; send text messages to both of the women in his life (their choppy composition making him sound drunk at any point in the night); and engage in all sorts of other activities. The broad picture is meant to reinforce the existential motif that every decision you make matters, no matter how minor it may be. Yet it’s a message the game bungles, considering both the decision to make certain activities not pass time and the specific choice of those activities (drinking, oddly enough).

Where Catherine is more consistent is in the interactions with other characters. Here, Vincent is encouraged to come out of his shell and engage with other people. This allows him to explore healthier relationships with other people in a relatively safe space, bridging the gap between self and Other and dissuading the notion that the latter is a pure threat to the former’s being.

Theatrical storytelling

But the most prevalent and most obvious form of engaging with Catherine isn’t pushing blocks or talking to people; it’s the complete lack of interaction. Most of the game experience consists of watching events unfold before you through cutscenes. Catherine strongly presents itself as a stage production, borrowing from several schools of thought to achieve this – a bit of the problem play here, a bit of existential theater there, all of it presented through a film noir lens – but the effect should be clear to anybody playing. From an aesthetic standpoint, these influences imbue the game with a stylish and distinctive quality. The character models look much like the Persona games, and the soundtrack is mostly riffs on classical music but is distinctly in the style of Shoji Meguro.

From a narrative standpoint, they put the player at a noticeable distance from the action, and in doing so, force them to consider the issues being discussed more deeply. Much of the story is a tragedy with Vincent playing the role of tragic hero. From the start he’s doomed to give into those vices he can never fully overcome. If the player is looking to fix Vincent’s problems once and for all, then they doom themselves to struggle in vain against his worst impulses. Instead, Catherine presents Vincent’s story as a sort of lesson or warning to the player: do not repeat his mistakes. “You are in a position to avoid these problems and fix your life”, the game says. “Don’t let that opportunity go to waste.”

Unfortunately, all of this only applies to Catherine in theory. In practice, the game falls well short of the goals it sets for itself. There are the plot problems, for one. There are a number of obvious, plausible solutions available to Vincent – admitting to the scandal before things escalate, leaving both women in favor of a life of peaceful solitude, quitting that drinking habit of his that causes him to cheat in the first place – that the game simply never explores. (In fact, Catherineconfusingly justifies his drinking habit by linking it to his speed in the puzzle segments: more beer equals quicker movement.) And why is it just men who are afflicted with the curse? Why aren’t there any ewes in the nightmares? Although the game pretends to have an answer for this question, all that bluff does is dodge the issue altogether.

This last issue – the absence of women navigating the nightmares – hints at much larger thematic problems Catherine is unequipped to solve. First, even if the writers wanted to deal with very general existential motifs, those motifs ultimately collapse into a very particular social situation (romance, relationships) because that’s the only way those motifs are ever expressed in the story. Second, the fact that those motifs have no place for women in them speaks to the inequality that underpins Catherine‘s narrative. The story reduces women to a mere presence in the male world and thus depicting them as inherently unequal to men. Anything that might humanize them – their own desires, flaws, insecurities – remain unexplored as the narrative, and attention remains fixed solely on Vincent.

One could argue that while the characters might see things this way, but the game itself never adopts such a perspective, and it’s an unconvincing argument for a number of reasons, primarily because the characterization and plot all reinforce that position in subtle ways. Particularly, in spite of his flaws, Vincent is still presented as a hero and the women in his life are defined only in contrast to that; they’re either outright villainous or as objects that exist only for Vincent to exercise his heroism upon.

When viewed outside of the gender roles, it still doesn’t entirely make sense. The game presents Katherine as the choice of of commitment and maturation, learning to truly become adult. But she is also not exactly a stable individual and even presented as villainous (she violently stabs a cupcake upon learning her fiance bought a new cell phone) and one can’t help to imagine that Vincent, even a more grown-up version of him, would be miserable in this version of adulthood. She’s mostly likely presented in this way to give some sympathy to Vincent, as a way to to excuse (or least explain) his indiscretions. It’s also likely that the over-the-top presentations of Catherine/Katherine were meant to be comical, which is acceptable within the confines of the story, but falls apart when trying to map its lessons onto real life experiences.

Plus, by the end of the game, the player will likely have contradicted the game’s lessons by answering its questions in bad faith. The further you get into it, the less likely you are to answer questions based on what you personally think and the more likely you are to answer them based on maintaining your current standing (which finale you want to get, of which there are three main ones, plus some more off-the-wall ones that feel more in place within a Persona fan’s fantasy). Judging by the post-choice survey results from other players (and the amount of consensus across all those choices), it would seem Catherine has failed at cultivating individuality in the player, as well.

Initially, Catherine enjoyed both financial and critical success, selling half a million units and earning all sorts of accolades from reviewers. Yet between the criticisms of the game’s questionable handling of gender issues and its poor handling of Erica, the game also represents the beginning of a much larger pushback against Atlus’ most popular franchise. Persona 4 was the first game under the spotlight as people began to critique how characters like Kanji and Naoto were represented within the game. Tokyo Mirage Sessions would only amplify Catherine‘s mistakes years later by uncritically repeating the false consciousness problem in light of a blatantly abusive entertainment industry.

Still, for all of its flaws, it deserves some credit. Though it flounders, the title can be forgiven for even attempting to represent the complexities of relationships and adulthood, compared to the ever-popular high school (or otherwise fantasy) settings of so many other video games, manga and anime. And some of its attitudes towards gender roles could be explained (though not excused) due to the Japanese culture which produced it, which generally has a more conservative view on certain womens’ issues than many countries, the United States included. And it is quite possible to ignore the issues with the game’s narratives and just focus entirely on the puzzle action – though from a single player perspective, this is very difficult as you can’t just immediately zip over all of the cutscenes. From its continued popularity as a competitive title, it’s definitely been accepted on that level by its fans. As a result, it leaves behind a mixed legacy like few any other titles.