- Chase HQ

As the initial entry in what would become a kind of Taito micro-verse, Chase HQ lit up the arcades of the late 1980s with its rapid sprite scaling, digitized voice samples, and cops ‘n robbers gameplay. Though an iteration on a formula made popular by OutRun and built upon Taito’s earlier racing game Top Speed, Chase HQ adds elements of the classic Hollywood movie car chase. The original upright cabinet was unmissable. Its police decals with matching blue lights and wailing cop sirens stood up well against the largely Sega branded competition, and with its arrival closely aligned with Beverly Hills Cop, Lethal Weapon and Miami Vice, it was thematically on point for the time.

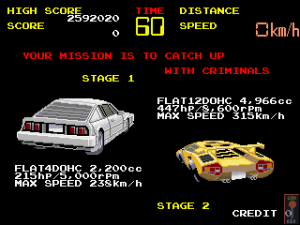

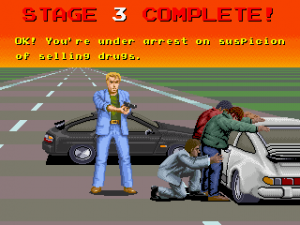

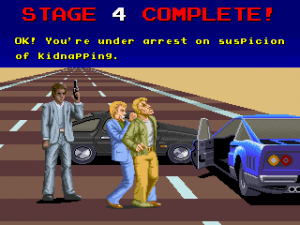

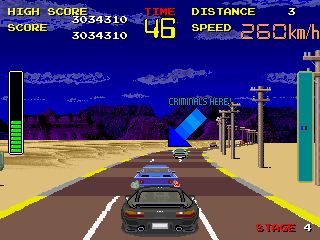

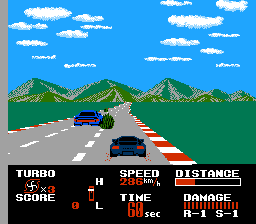

The action is split across five stages, with each stage divided into two distinct sections. First, you drive your undercover police car (which looks a whole lot like a Porsche 928) against the clock in pursuit of your assailant. You also have a limited number of turbo boosts that temporarily increase your speed (an idea later used by Sega in the less-than-great Turbo OutRun). The distance is helpfully displayed on the screen, so you can determine when you’re closing in. These stages have branching paths, another element from OutRun, and you need to take the correct one or else you’ll end up lagging behind your target. Once contact is made, your siren comes on and the timer resets, as you now have to destroy the criminal’s vehicle using your own car as a weapon. The enemy’s damage bar appears on the left hand side, with a radar on the right. Once you’ve inflicted enough damage, your opponent stops, the cuffs come out, and it’s onto the next mission. If you run out of time, you can replenish the clock with another credit, though if you’re engaged with an enemy, this annoying replenishes their health meter too.

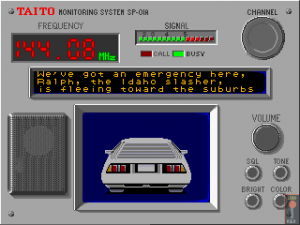

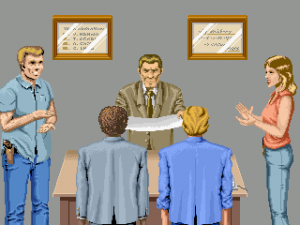

The real magic of Chase HQ lies in the atmosphere it creates within this simple framework. There’s tons of digitized speech, as each level opens up with orders from your operator Nancy, while the chatty protagonists Tony Gibson and Raymond Brody offer exciting commentary. The slap bass heavy music from Takami Asano (the guitarist for the band Godiego) keeps up the tension, and while not instantly memorable, certainly has some stand out moments. This, alongside the satisfaction you get from ramming the enemy cars off the road, puts the sensation of sideswiping a rear bumper up there with landing flurry of blows in Streets Of Rage. It just feels so right.

The job of capturing the magic between the pixels for the home was always going to be tough, and alas so it was. In the west, home computer versions were handled by Ocean, a marquee synonymous with quick and sometimes dirty conversion work. On this occasion they managed to turn in some respectable ports, given the capabilities of the era’s hardware.

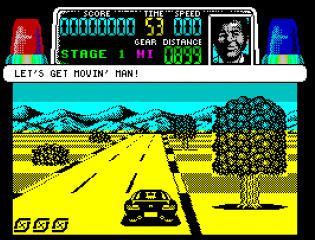

The Spectrum version, with its monochromatic vistas and juddery roadside objects, is very much what you would expect from the platform. Even the one channel theme music is unashamedly Speccy whilst being a fair tribute to the arcade machine, but the conversion itself is a somewhat flat experience, even back in 1989. The C64 effort is a curious mashup of the machines graphical modes, the result being that the main car sprite blends into the scenery about as well as orange juice blends with milk. A crying shame, as out of the 8-bit home computers, this was most likely to be the machine that brought the arcade experience home. The MSX platform shares graphic assets with the ZX Spectrum version but plunging new depths of framerate, only improved by rapidly blinking your eyes during play in order to smooth out headache inducing jitteriness. The surprise home micro port is the Amstrad CPC release, which pushes the hardware about as far as possible, and perhaps a little bit beyond. Sampled effects and voices are lifted from the arcade and while the action is a far cry from that found in the original, the scaling roadside objects and moving horizon create an enjoyable, if somewhat more leisurely experience.

Versions were also created for the Amiga and Atari ST, but we can only wonder how much facetime the developers had with the arcade original. The once iconic Porsche now resembles a featureless black digital slug, rendered at about a quarter of the expected size. The framerate is firmly in the single figures and the limitations imposed by the single fire button setup results in an exercise of pure frustration. Neither were worth the budget asking price.

The Japanese home computer conversions are an even more perplexing breed, and fascinating given their obscurity. Looking the part at least was the Ving published port for the Fujitsu FM Towns Marty. The digital streaming audio of the arcade soundtrack goes some way to provide a sensation of the original work. The sprites are colorful, vibrant and most importantly, accurate with some nice added touches. Even a politely worded option to “Listen to the music” exists within the game settings. It’s disappointing then to find that, somewhere along the way, the DNA has been lost and the end result is an unfortunately hollow experience. The mid-level road branching options seem to be of no consequence. The initial two stages provide no challenge. Some curiously off point collision detection seems to have also found its way into the mix.

The Sharp X68000 port is woeful considering the machines chipset being not dissimilar to the original arcade board. Odd, misshapen and immoderately pixelated cars judder down a concrete corridor of broken perspective, painfully arriving at the bottom of the screen to loiter and obstruct your progress. Control input is often so laggy, you question if this is actual gameplay or just a rolling demo. You can only imagine one of gaming’s great untold stories exists here, but on a more positive note, we do get some high quality renditions of the soundtrack thanks to the Yamaha YM2151 sound chip.

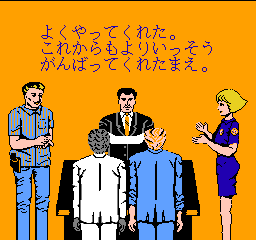

Conversions for the Sega Game Gear, Master System and Famicom provide at least a glimmer of the adrenaline found in the arcade. These versions are notable for altering and expanding the gameplay to make it more palatable for home audiences, even though the end result is somewhat simplistic. The Famicom version has some nice sampled speech from Nancy at Chase Headquarters, but our cop buddies are voiceless in this particular iteration. Now included is a shop, allowing the player to upgrade aspects of the car and purchase additional turbos with money earnt from completed stages (it would seem cops are paid per arrest in this particular version of the Chase HQ universe). While mildly interesting, the impact of these upgrades is minimal. There’s no seven stages rather than five, but once completing the final one, you’re sent back to the start to play again. These loops are handily titled as “Rounds” and feature a few cosmetic changes to the scenery and ramped up difficulty. Even our cast of previously captured criminals are present, seemingly let out on the road again after an evening in the slammer. You need to complete three of these Rounds to truly finish the game, which is a tough time with no continues.

Famicom

The Famicom version sets itself apart with its Arkanoid controller compatibility, which is a handheld spinner device that would plug into the front expansion port allowing for analog control. A neat little touch in what is a fun and thoroughly playable version of the game. Unsurprisingly, for a machine with the processing power of an egg timer, the humble Nintendo Game Boy boils the action down to almost primordial levels. In place of a 159mph thrash to justice (as indicated by the on screen speedometer) we have a lonely, and rather featureless 50mph drive down a barren freeway that has more in common with Desert Bus than Chase HQ. Car battles are even less thrilling, your sense of urgency propelled by the need to end the ear bleeding in-game siren, rather than taking down your opponent.

The version produced for NEC’s PC Engine is probably the best of the console bunch. The frantic and possibly too fast gameplay has you ricocheting off opponent cars like a glass marble hitting a tiled floor. Initial frustrations do eventually lead to an enjoyable game, with all the main aspects of the arcade ported over successfully. Like the Famicom version, there’s some speech from Nancy at the beginning of the stages but no one else. This version also offers a hidden sixth stage accessed if you score over five million points. An upgraded and reworked port of Chase HQ was also developed for the Genesis, though this was named Super HQ in Japanese, and renamed Chase HQ II for Western territories.

Perhaps the most beguiling home version would be the Japanese exclusive Sega Saturn release, packaged as it was alongside the arcade sequel SCI Special Criminal Investigation. While undoubtedly looking the part, the car handling feels wrong, and the music is slightly out of tune, making for an overall degraded conversion.

It was not until Taito Memories II Gekan collection on PlayStation 2 that an arcade accurate Chase HQ was finally accessible, albeit only in Japan. This version is straight up emulation and manages to map the arcade controls over to the DualShock 2 with minimal harm to the gameplay. One can only guess that Taito knew it was walking into a legal minefield with future western ports of Chase HQ, with many of the graphical assets looking a little too similar to their real life counterparts and obtaining official licenses would no doubt prove to be prohibitively expensive.

Outside of all these ports, Gibson and Brody would reappear in 1989’s arcade exclusive side-scrolling shooter, Crime City. The Chase HQ series would of course continue on for several subsequent entries.

Screenshot Comparisons

Arcade

Saturn

Atari ST

Amiga

Commodore 64

Amstrad CPC

ZX Spectrum

FM Towns

X68000

SMS

Famicom

Game Boy