NA Boxart

EU Boxart

Back at the dawn of the new millennium, Grasshopper Manufacture was paying the bills by helping out on the development of the Shining Soul duology on the GBA, a reboot of the Shining JRPG series. Directing this project was a man named Akira Ueda, a former Square graphic designer who joined Grasshopper back in 1999. He seems to have gone his own way down the line, with his last credit with them being with No More Heroes 2, but he left an unmistakable mark before then. He directed the two most out of place games in Grasshopper’s library: 2004’s Michigan: Report From Hell and 2006’s Contact, both bizarre classics in their own right, with Contact having a much more clear creative stamp.

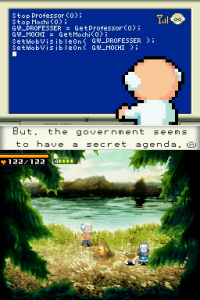

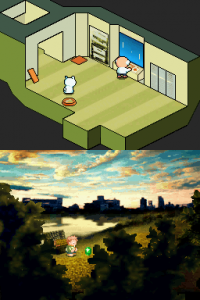

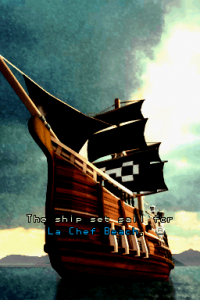

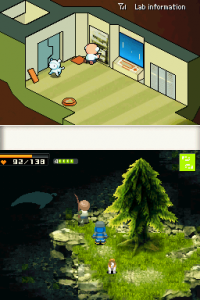

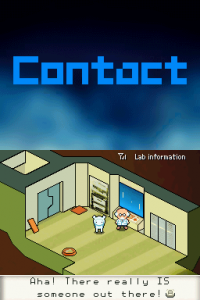

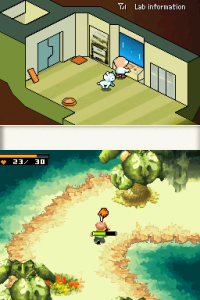

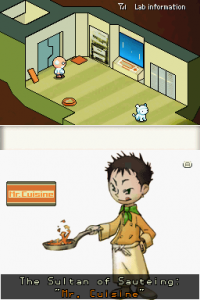

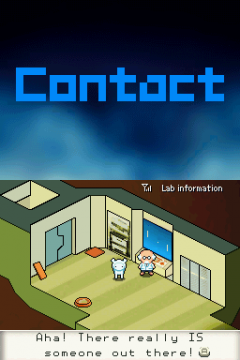

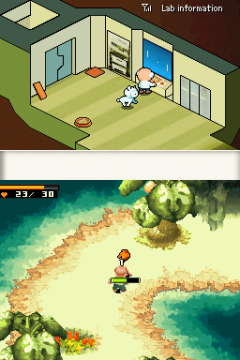

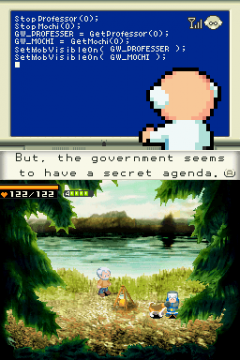

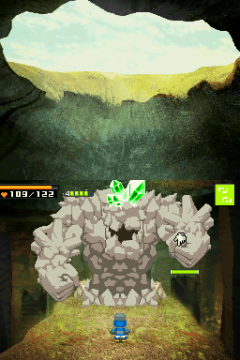

The best way to describe Contact is as a Mother-like with a heavily simplified proto-CRPG battle system with a dash of Grasshopper style forth wall leaning. The game is aware of you, the player, right away, with a professor in a sort of faux 16-bit graphical style directly communicating with you and asking for your help. His space ship is being attacked by an unknown enemy and ends up losing his power cells on a 32-bit GBA graphics style isometric world. A young boy named Terry ends up involved and has to help the professor find the power cells to return home, with you guiding him. Your ultimate enemy ends up being a terrorist organization called the CosmoNOTs, and your adventure will take you to all sorts of places, including ancient ruins, tropical islands, and military bases where you kill actual human beings and watch their skeletons dissolve, just in case you thought this game was going to be normal.

The most frustrating thing about Contact is that its story doesn’t give you any real closure. The majority of the game is a generic JRPG story, just with a mild sci-fi and meta narrative flavor alongside a quirky sense of unease, and then proceeds to completely lose its mind at the end – and gives a cliffhanger that was never followed up on. Ueda wants to return to the series, but since he seems to have moved on and his relationship with Suda 51 and the rest of Grasshopper’s management is a big question mark now, it’s doubtful we’ll ever see a sequel. It’s a shame, as the game has some heartfelt moments and some good gags to match, but it needs an entire new chapter to give it the impact it should have.

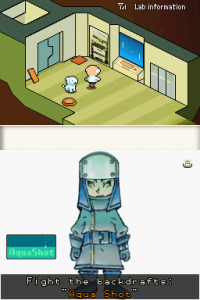

The actual gameplay here is bizarre, to say the least. Terry technically acts on his own, and you help guide him. You can set him in battle mode, and he’ll attack nearby enemies once you move him in range. You can also use special moves you unlock through costumes and improving stats, which only go if you order Terry to use them. There’s strategy here, including getting the hang of attack speed and figuring out how to aggro single enemies instead of groups, making the system pretty engaging. Where you start hitting a wall is how experience works.

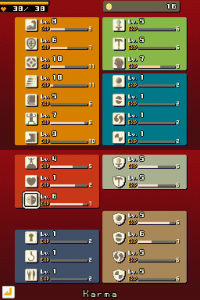

Instead of having a hard level growth where you get skill points to spend, everything has a separate experience and level bar. You do something enough and you get better at it, ala Final Fantasy II. This even extends to elemental resistances and your defense. The issue with this is that you hits a lot of difficulty spikes, and experience is scaled in a way where it can be difficult to actually earn it in more manageable fights. Hit a new area and you’ll suddenly find yourself not ready for the new enemies thrown at you, slowing your progress. It’s also worth mentioning that doing actions like cooking is also affected by this same system, so it requires you to cook dozens of dishes before you reach any sort of level of quality cooking.

Contact is a grind, and while there’s possibly some thematic reasoning behind it, that doesn’t excuse just how much grinding there actually is. Even the costume system, which grants you different buffs and powers, starts becoming tedious as those costume skills also require grinding, and you can’t switch costumes on the fly. It really holds it back, which is disappointing, because the game is loaded with interesting moments and ideas.

The meta elements do go in an interesting direction, raising themes of free will and deterministic paths, and the actual motivations and goals of much of the characters are purposefully obfuscated for both you and Terry. The otherwise generic worlds have moments of charm or even a bit of realism, due to how death is treated as permanent and significant. There is weight to your adventures, stakes you don’t often feel so much as you do in most other JRPGs. The whole game is a deconstruction of the traditional JRPG design style and narrative line, something Ueda would know a bit about as a classic mainline Final Fantasy staff member.

There are weird ideas here that should be revisited as well. The sticker system acts as both an equipment system, where you get random buffs you can add on, or as methods of special attacks with all sorts of strange qualities. The first you get is only as strong as how happy you make the professor’s dog, which you can briefly play with whenever Terry sleeps, which you have him do to save. It’s hard to think of another game that has such a level of tone dissonance on purpose as seeing a bunch of military soldiers involved in illegal experiments spinning around like a child playing helicopter and then having to explode their skeletons out with sword stabbing. There was even a sort of multiplayer aspect with the WiFi island system, where people you share friend codes with can show up in your single player game with special items. There’s a vision here that’s well realized, and should be fleshed out further.

It’s difficult to recommend Contact. It’s extremely flawed and can really wear you down if you play it for long bursts and spot the poor gameplay loop, but it’s an original you won’t soon forget. It’s a game weird even by Grasshopper standards, for both better and worse. If you value quirkiness or originality, you should at least give this a shot. Everyone else, if you’re interested, just pace yourself.