When it comes to storytelling in Japanese video games, two of the most well reknown companies are Chunsoft and Spike. Chunsoft was the developer of the Famicom version of Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken, the game that started the mystery adventure game craze during the 8-bit era, as well as numerous well regarded sound novels like Kamaitachi no Yoru (known as Banshee’s Last Cry for its 2014 English localization) and Machi. Spike was formed from the ashes of Human, who put out daringly innovative titles like Clock Tower and SOS/Septentrion. In 2012, the two companies merged to form Spike Chunsoft, with their most popular title being Danganronpa, an adventure game published a year earlier from the Spike side of the company.

Danganronpa is, at heart, a murder mystery, wrapped up in the trappings of modern anime pop culture, complete with outlandish character designs, a stylish soundtrack, and plot twists after plot twists. The core of the games focus on a group of high school students, each having an “ultimate” skill, who are trapped together and forced to kill each other if they want to leave…but only if they can get away with it, after being judged in a courtroom session. The title translates to something along the lines of “Refute Bullets”, a reference to the action elements found in the game’s courtroom debates. The English title of the first game is Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc, in order to establish the “gun” motif.

The series draws from numerous other inspirations. The murder mystery and court proceedings are very obviously borrowed from the Ace Attorney games. The stylish interface design and the social-sim elements skim from the later Persona games. Its “quirky characters trapped in an enclosed area” feels a lot like Spike Chunsoft’s own “Escape” series (999/Virtue’s Last Reward), and “command teenagers to kill each other” scenario hails back to the novel/manga/movie Battle Royale. The stories for the series are written by Kazutaka Kodaka, who cut his teeth writing for the later entries in the Tantei Jinguuji Saburou series (known as Jake Hunter in English). He admitted that the sordid storyline was partially inspired by the twisted Dreamcast horror/comedy game Illbleed. Artist Rui Komatsuzaki supplies the character designs.

Please note that it’s very, VERY easy to accidentally spoil yourself on the Danganronpa games. There are many twists and turns of the series, the least of which are what characters live and die. Don’t read wikis, any of them, and don’t look at fan art. Sometimes even official merchandise can spoil things. Simply typing their name into Google with autocomplete on can clue you into a characters fate. With this in mind, the main reviews for the two Danganronpa games includes only screenshots from early in the game. There are two separate pages feature screenshots which will spoil parts of the game, and are only intended for players have completed them. Be careful!

Makoto Naegi is an average student who has somehow found himself enrolled in Hope’s Peak Academy, a gathering place for Japan’s most talented students. His first day of studies, however, end up being far worse than he ever imagined. After entering the front door, he passes out and wakes up to a deformed version of the school, where all windows are bolted and all exits are sealed. He’s joined by fourteen other students, all suffering from the same memory loss.

A walking, talking teddy bear named Monokuma emerges and joyfully describes their predicament – they are trapped at Hope’s Peak Academy, as part of a killing game. The only way to escape is to kill another student and get away with it, which is decided in a courtroom setting. If the murderer manages to escape conviction, then they are freed from their prison and the rest of the students are killed. If they are successfully found guilty, then they are executed in a overtly ridiculous fashion.

Most of the game is played from a first person perspective, as you walk around the room and interact with or look at objects. As with most other similar games, the plot is linear and advances automatically once you’ve completed specific objectives. Each day is structured similarly. You’re allowed to explore an area, then retire to your dorm after you’ve examined everything important. Then there are a few days of “Free Time”, where the social elements come in. You can hunt down any of the surviving students and choose to hang out with them, which reveals some of their back story and grants skills that can be used for the trials. In order to speed up your relationship, you can also purchase assorted items from the school store and give it to them. The currency, Monocoins, are obtained by investigating optional items, as well as a reward for performing well at the trial.

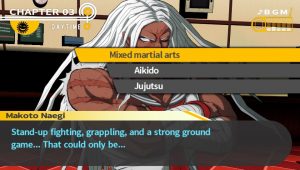

Eventually, a body is discovered, where you investigate the murder scene and the surrounding areas, piecing together all of the evidence and gathering testimonies, before finally being called in for a trial. The court battles are patterned after Phoenix Wright, though with its own spin. The courtroom is set up in a circle, with each of the surviving students giving equal voice in the debate. The player character typically takes on the role of the defense, but the role of the prosection is fluid, depending on what’s being discussed. The flow, however, is pretty similar – usually there’s a suspect, but they’re almost never the real killer, who is eventually implicated before breaking down, and then admitting defeat.

The debates are broken down into segments. The roundtable arguments are most similar to Phoenix Wright, as the students deliver a canned series of statements, and you need to pick out the contradictions. However, rather than picking out a certain statement, there are a handful of highlighted phrases peppered throughout. These are the phrases you need to attack, and you challenge these via “truth bullets”, which is a stylized way to say “evidence”. The statements float and spin across the screen, and you shoot them with a targeting cursor. Your “gun” comes preloaded with specific truth bullets, only one of which is correct, so in practice the evidence you can use is greatly narrowed down. Higher difficulty levels add extra highlighted phrases and load more bullets, making it less clear as to which are the proper arguments that need tearing down.

At times, the discussion changes, requiring that you simply present certain pieces of evidence, or implicate a certain person. There are a handful of other minigames though, too. When the player character tries to think of a specific word, you get to play the Hangman’s Gambit, where you need to assemble a phrase out of floating letters. These segments are so easy as to be trivial.

At some point accused characters start rambling and need to be defeated with a rhythm game called Bullet Time Battle. Out of all of the abstractions and metaphors Danganronpa uses in the courtroom setting, this one probably makes the least sense, if that says anything. You basically just tap buttons to rhythmic dance music, which routinely changes tempo, in order to shoot down arguments.

As with Phoenix Wright, if you choose the wrong statement, you lose a bit from your “influence” (life) bar. Each segment is also under a time limit. If either falls to zero, then Makoto is judged guilty and you technically lose, though you can restart the segment with no real penalty other than lowering your score. There is also a separate “focus” bar, which is used to slow down time to make statements easier to hit. There are a few dozen different skills you can get, depending on the Free Time segments, which can make many of the minigames a little easier. However, none of them are mandatory, and they don’t have a huge effect of the game anyway.

Before the trial ends, you’re challenged with placing all of the events of the murder in chronological order. This is presented via an incomplete comic, and you’re given a selection of panels to fill in the blanks. Complete to how high energy the court room segments are, this climactic event is oddly low key, but not in a bad way, since it allows you to logically piece together everything without being distracted by some of the other, more gimmicky elements. As always, there’s still a little bit of guesswork involved in trying to figure out what each panel actually represents, since they’re just tiny drawings, but the blank spots tell you what’s supposed to be happening.

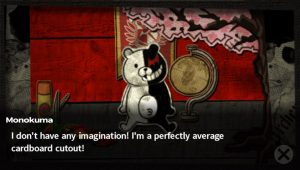

The elaborate mysteries are part of the series’ appeal, of course, but its popularity also lies in its presentation. The surreal atmosphere is inspired by Goichi Suda games like No More Heroes, particularly its fascination with retro 8-bit style pixel graphics. The visuals are presented as sort of a dream-like reality. Rooms are assembled from scratch every time you enter them, walls folded in like paper and furniture plopped in like doll toys, as they’re dioramas being assembled by forces unseen. Characters are represented as 2D cardboard cutouts, and you interact with them by literally flinging question marks. All of the blood is pink, its bright coloration contrasting with the grotesqueness that a murder scene usually provokes.

It’s hard to figure out which of these were practical limitations and which were intentional – it’s probably both. The cardboard cutout characters allow the camera to move around in three dimensions while keeping the same 2D character portraits, eliminating the need for potentially janky polygonal models. And the pink blood was probably a way to get around CERO’s dreaded Z rating, a designation typically relegated for violent Western-developed games and other bits of exploitation. It’s all very clever.

The distinctive soundtrack is composed by Masafumi Takada, who worked on several Grasshopper games including Flower Sun and Rain, Killer7, and both No More Heroes titles. It’s also one of his best works, keeping his talents with using simple but catchy motifs, and creating a wide variety of songs with varied instrumentation. Everything from Monokuma’s lighthearted theme song to the high intensity courtroom battle themes come together to form an incredible soundtrack. One of the standout songs is “Box 16”, an extended version of the standard investigation theme, partially rearranged with guitars. This point in the game is the climactic chapter, where all of the mysteries start to unravel, and this track indicates that things are most definitely getting serious.

The writing, too, is generally excellent. The characters may seem one dimensional at first, but that’s the point – they’re all archetypes that take their single dimension and ramp it up to the extreme. There is a certain point where their shtick can become tiresome, although typically these characters are disposed of before it becomes grating. Their personalities are fleshed out a little more in the Free Time events, and the ones that do stick around for the long haul end up being well developed. It’s also a funny game too. There’s an unseen/unnamed character who acts as a tutorial-giver, apologizing profusely and prostrating him(it?)self in front of the gamer for barging in and breaking the forth wall. Some of the funniest jokes are the PSN trophy names, but just make sure not to check any lists lest you spoil yourself.

The cast of characters is highly amusing, and you will undoubtedly pick out favorites. But stastically speaking, one (or more) of these favorites will either (a) be murdered, or (b) murder someone else, which by the rules of the game, will eventually cause them to be executed. There’s heartbreak in watching them disposed of, or disappointment that they’ve decided to take killing into their own hands. Along with that, there’s also a certain perverse enjoyment when someone you found annoying is disposed of. The executions are a lurid part of the appeal, just because they’re so bizarre. Unlike the murder scenes, there’s rarely any gore. But they are simultaneously gruesome and hilariously impractical, and puts a much more literal spin on “cruel and unusual punishment”. One of the first movies you see when you start the game is Monokuma strapping a hapless man into a rocket ship, sending it flying into outer space then tumbling back down to earth, revealing that the body has burned up to become only a pile of bones. What is a little disappointing is that the punishments aren’t always consistent. Some are developed in an ironic matter, fitting for their personalities. Others, not so much. One doesn’t even make sense unless you happen to be familiar with a American folk tale that’s barely known in its home country but happens to be classic in Japan.

Danganronpa walks a tight rope when dealing with the tonal shifts. The execution sequences are absurd and cartoonish, but the characters are understandably distraught at how horrible it all is, making for some bizarrely dark comedy. It’s especially painful watching the facial expressions of the condemned, as they’re caught somewhere between fear, disbelief, despair, and finally acceptance. Monokuma captures these duelly sentiments perfectly, a teddy bear who’s half cuddly, half monstrous, who cracks bad jokes and routinely breaks the fourth wall, all while callously provoking murder. It’s not easy to create a character that can best be described as “loveable psychopath”. The key themes are the dueling nature of “hope” versus “despair”, as the Ultimate students, all exemplary in some way, are reduced to callous murder. It’s not subtle either – like many Japanese story oriented games, the themes are pounded into your head, over and over, to the point where it feels overwritten.

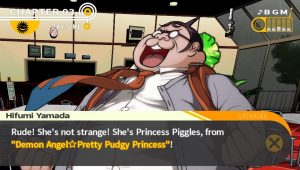

The culture gap proves to be a small problem with the English localizations. The translators kept many of the Japanese pop culture references intact, running under the assumption that their target audience is either aware of it, or has the resources to research and understand it. It makes reference to anime, manga, and even old TV shows, many of which were never officially translated into English. If you’re familiar with these works then it’s amusingly gratifying, but those that aren’t will find themselves in the dark, wondering what exactly they’re missing.

One particularly important element lost in the localization is Monokuma’s voice. In Japan, he was voiced Nobuyo Ohyama, the same voice actress that’s been the voice of Doraemon, the loveable time traveling robotic cat, for over thirty years. For Japanese gamers, it’s something of a mindscrew to hear such sadistic words spoken in the voice of a childhood cartoon favorite. The English speaking equivalent probably would’ve been something sounding like Winnie the Pooh or Mickey Mouse, but instead he sounds like Teddy from Persona 4, right down to the occasional bear pun. This wasn’t a bad choice by any means, and the actor does a great job with the character, but it just isn’t the same. In fact, the voice acting in the English version is routinely outstanding, though the original Japanese voices are included for purists.

Danganronpa is a game that begins starts off as being darkly compelling and as the plot twists pile up, ends up even crazier as it goes along. If the story has any major weakness, is that most of the twists are revealed in the final moments of the game, which then leaves on a cliffhanger, to be (mostly) resolved in the sequel.

The game was originally released in Japan in 2009 for the PSP, then re-released on the Vita in 2012. In Japan, the Vita version features both the first and second game, but the English localized version was broken up into two separate releases. The differences between the two versions are minimal. The Vita version has crisper, higher resolution graphics, and touch screen controls. As a minor change, the “results” screen from completing each minigame has moved right to the end of the trial.

The only real addition is the “School Life” mode, a simulation mode unlocked after completing the game. This mode was introduced in the second game, and retroactively added back here for the Vita release. It’s an alternate scenario where Monokuma compels the students to build clones of himself instead of being forced to kill each other. Here, you have to assign each of the students to various rooms in order to mine for items, which are used to create things at Monokuma’s request. You also need to routinely assign students to clean or take rests, so it’s essentially one big balancing act.

After spending the day working, you can socialize with the other characters, which are identical to the Free Time events in the main game. Since some characters are killed so early during the main game, it’s incredibly difficult to flesh out their backstories unless you plan things out ahead of time, so this lets you hang out with them without worrying about the plot. Once you’ve completed their Free Time events (and in a few cases, completed other objectives), the characters will give you a pair of their underwear in the ending, as a strangely revealing memento of your intimate bond.

There are 50 days to complete Monokuma’s various requests, and each specific requests is also required to be completed in a certain number of days. The game insists that it’s possible to beat on the first run, but the randomized element makes it very difficult to find items consistently unless you know its tricks, making it hard to fulfill requests in time. However, the students level up their skills over time, and you can replay School Mode over and over with their levels intact, making it easier in subsequent replays. Successfully completing Monokuma’s objectives will give you tickets, allowing you to take other students on “dates”, allowing you to further level up your friendship if you go to the right places and pick the right dialogue options.

An English fan translation for the PSP version was released in 2013, just shortly before Nippon Ichi America confirmed plans to officially localize the Vita versions. The patch only works with “The Best” budget re-release of Danganronpa, which included some extra gallery artwork and some other minor tweaks over the original release. The major difference between the official version and the fan version is the translation, something which causes consternation amongst hardcore fans. One of the biggest points of contention is the localization of the word “Chou-Koukou-Kyuu” – the fan translation calls it “Super Duper High School”, a different fan translated Let’s Play referred to it as “Super High School Level”, while Nippon Ichi’s official translation is simply “Ultimate”. The fan translation also uses the Japanese name of the school, Kibougamine, versus the English translation and the one in the Let’s Play, Hope’s Peak.

In 2016 and 2017, both Danganronpa and its sequel were ported to Windows, as well as the PlayStation 4. It benefits from a smoother framerate (not like this is necessary in a game like this) and higher resolution visuals, though the assets (the portraits, etc.) are still designed for the same resolution as the Vita. It still looks decent, though.

Characters

Makoto Naegi – Talent Unknown

The hero. An average kid who seems to lack the Ultimate skills of his classmates, giving him an inferiority complex.

Toko Fukawa – Ultimate Writing Prodigy

An extremely well respected author, who somehow seems unable to properly interact with the male gender. (Or anyone, really.)

Sayaka Maizono – Ultimate Pop Sensation

A member of a popular Japanese singing group, who also happened to know Makoto in middle school, forming an instant bond between the two.

Kiyotaka Ishimaru – Ultimate Moral Compass

Nicknamed Taka, he plays everything by the book in a comically over-the-top manner. His Japanese title indicates he is the ultimate member of the “discipline committee”, something unique to Japanese high schools (or, rather, anime/manga set in Japanese high schools), hence the rather strange translation.

Dressed in elaborate gothic lolita attire, Celestia has a stern attitude that conceals her motives, appropriate for her role as the Ultimate Gambler. She insists that her fanciful name is real, even though (the game tells us) she looks Japanese.

Junko Enoshima – Ultimate Fashionista

A world famous fashion model who’s appeared on the cover of innumerable magazines.

Monokuma

A stuffed teddy bear and tormentor of the students. He regularly gives standup comedy shows that barely make any sense. His name is a portmantearu of “monochrome”, due to his split white/black coloring, and “kuma”, the Japanese word for bear.