The ZX Spectrum scene of the ’80s is always difficult to pigeonhole. The computer was a viable platform for almost a decade, and many developers came up with interesting ways to tackle it’s technical limitations. Because of the small development teams, many computing magazines were quick to champion individuals and their accomplishments. Chris and Tim Stamper of Ultimate Play the Game and Greg Follis and Roy Carter of Gargoyle Games were treated like pioneers, people worth three or four pages of coverage in rags otherwise riddled with short review blurbs and tons of advertising space.

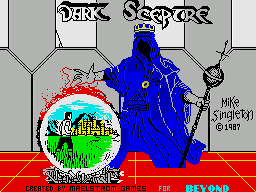

One of these often heralded heroes was Mike Singleton, a designer who truly pushed the limits of convention. Lords of Midnight and its sequel Doomdark’s Revenge were critical darlings, receiving perfect scores in multiple publications. Their combination of adventure, strategy, and RPG elements creates a unique experience that few games can replicate, putting Singleton and publisher Beyond Software to the top of UK computer scene.

At the forefront, Singleton did not have a difficult time getting developers to work for him. Developers quickly snatched up his grand, far-reaching strategy game designs. Years before Warcraft and Dune 2 caught on, Singleton came up with several real-time strategy games. While none of them were like Command & Conquer in terms of resource or unit management, the simple combination of strategy elements with real-time gameplay remains forward-thinking in a time when most companies were churning out generic shooters.

Beyond Software published 1985’s Quake Minus One, a game where the player controls multiple robots as they cruise down paths to re-take control of a giant computer installation. A year later, Consult Computer Systems developed Throne of Fire, a Singleton designed game where the player must control a prince and ten henchmen on a quest to fight the other successors to the throne. The strategy elements of these real-time action games, while innovative in hindsight, did not thoroughly woo critics.

During this time, Beyond was bought up by Telecomsoft. Most of Singleton’s future games would be published under Telecomsoft’s Firesoft label. At some point in 1986, Singleton formed Maelstrom Games, a small development team with virtual unknowns Alan Jardine and David Gautrey. This team worked on numerous Singleton-led titles up until the mid-’90s, including the maligned Lords of Midnight: The Citadel and Ring Cycle. Future missteps aside, Maelstrom’s first game was the ambitious and critically-acclaimed Dark Sceptre.

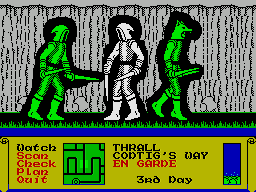

Preview screenshots appeared in the summer of 1986, showing a side-scrolling adventure/strategy hybrid that played out in real-time. Two versions of the game were developed simultaneously: a standalone single-player version and a play-by-mail game conducted by Singleton himself.

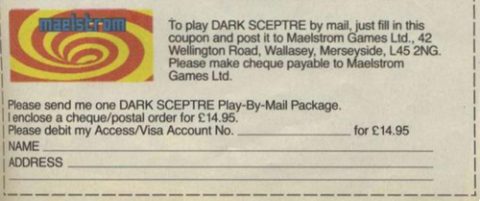

Advertisements for the play-by-mail version quickly popped up August, requesting a relatively small fee of £14.95 for a massive kit that included a master cartridge, an episode cartridge, the play-by-mail program, a promised copy of the as yet unreleased single-player version, instruction manual, and coupons for three episodes. Episodes were presumably the individual multiplayer games. Additional episodes were £1.50 after that, although it’s unclear how many episodes were ever run and how many people were ever playing at one time.

The play-by-mail form. The reader cut these out of adverts in various magazines and mailed them into Maelstrom.

The play-by-mail form. The reader cut these out of adverts in various magazines and mailed them into Maelstrom.

Several magazines discussed the play-by-mail game before it was released. Gamers would record their turns onto a ZX Microdrive cartridge, then send them to Singelton. He would enter in all of the commands and let everything play out, then mail the cartridges back. Unfortunately, no magazines actually covered the finished product, making it likely that only a handful of players ever received the full Dark Sceptre multiplayer experience.

After languishing in development for over a year, the single-player version of Dark Sceptre was finally released. With a bare-bones instruction manual and complex game mechanics, it’s probable that everyone was very, very confused.

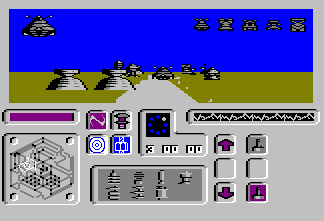

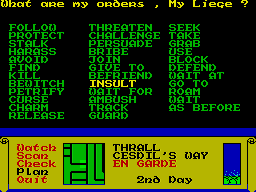

The game controls are straightforward, with support for a single-button joystick or four direction buttons and a select key. To start, the player has many warriors they can alternate between. Players can view the map, check the status and attributes of fighters, issue orders to individual characters, or save and quit.

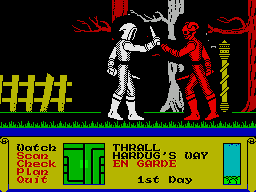

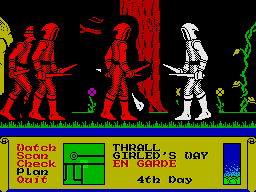

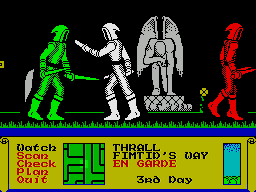

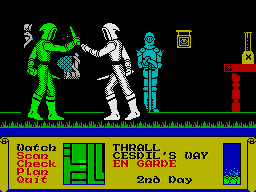

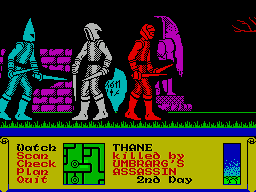

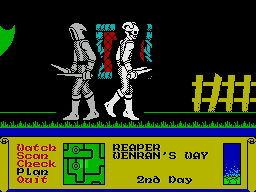

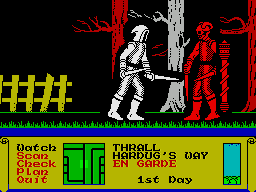

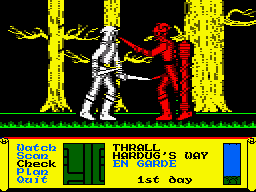

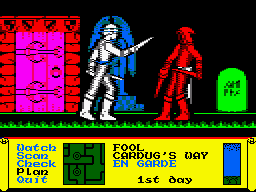

There’s not a whole lot of time to get adjusted before Dark Sceptre punishes the player. Just as your gathering your bearings, a red skeleton warrior who is clearly holding the titular Dark Sceptre approaches one of your fighters and enters battle. The player’s feeble hooded man is instantly killed, and the red warrior walks away. This red beast is your true objective, although tracking him down proves to be a massive challenge.

The manual elaborates on how the red warrior and the scepter came to be. The Lord of the Isles of the Western Sea grew wary of new immigrants, the Northlanders. Proud and boastful people, they coveted the entire land. To stop them taking control, the Lord has his people craft the a scepter with which he intends to kill his strong foes. When the Lord attempts to use it, the Northlanders instead transform into Lords of the Shadow, evil creatures who must do the malevolent scepter’s evil bidding. The player is tasked with obtaining the scepter. The manual says you also need to destroy it, but the game simply ends once the object has been obtained.

The player commands eight different warrior classes, most of which have very specific uses throughout the game.

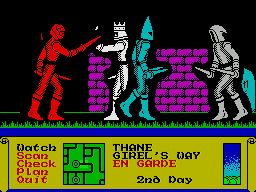

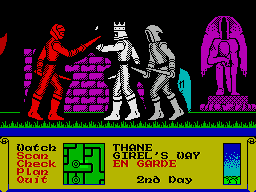

Thane

The crowned thanes are the strong commanders of your units. Their presence is required in order to maintain your troops. If you find yourself without any thanes during a game, the likelihood of troops abandoning your cause increases exponentially. While he’s capable of taking care of himself, the thane is best surrounded by lesser units to ensure his survival.

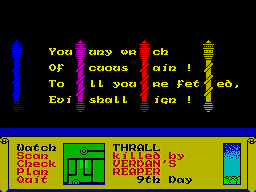

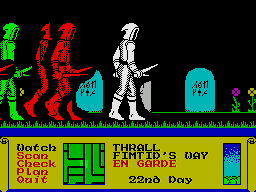

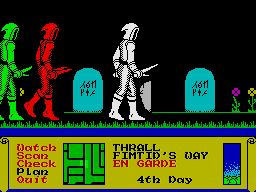

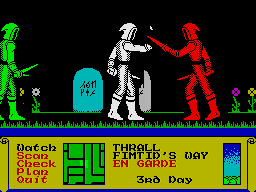

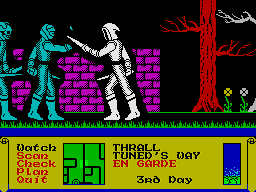

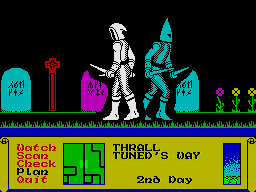

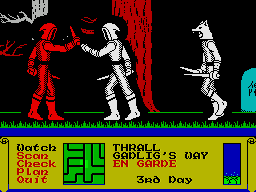

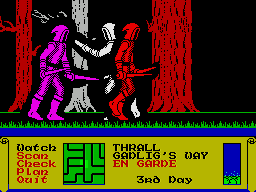

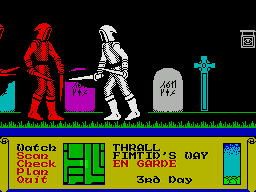

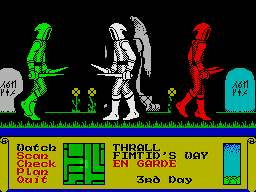

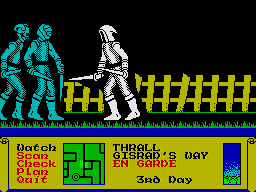

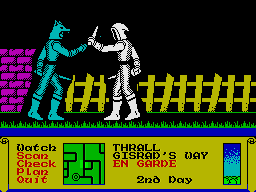

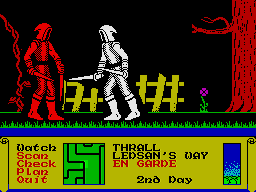

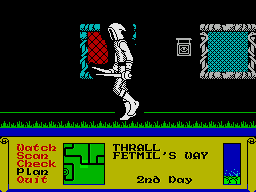

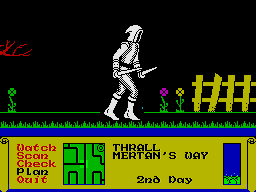

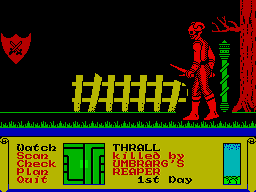

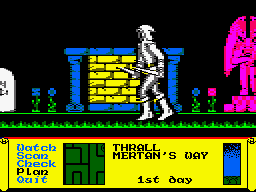

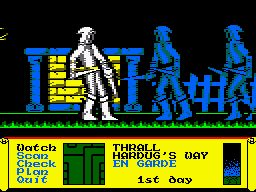

Thrall

Thralls are essentially pawns. Some might have strong attributes or skills, but they are limited to only a couple compared to the other units. They’re great fodder for stronger enemies and can whittle down opposing forces pretty well, but like in any strategy game, these peons will do an awful lot of dying before you obtain the scepter.

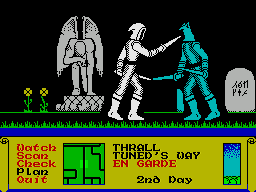

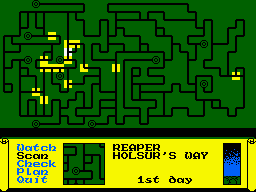

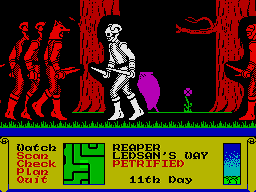

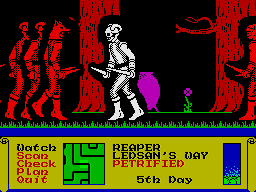

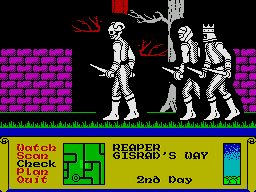

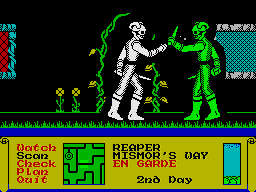

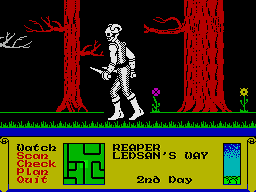

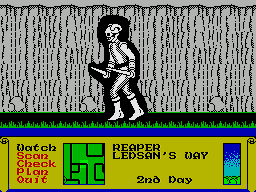

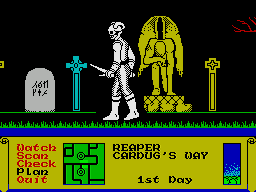

Reaper

Reapers are skull-facced warriors that are generally tough. The manual says they strike fear into the heart of their opponents. Whether or not this is the case, he does a good job at accomplishing tasks by force. He is most able to use the threaten and challenge commands, although he is best used in combat situations.

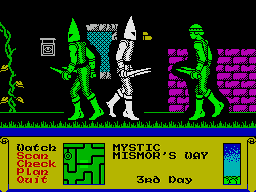

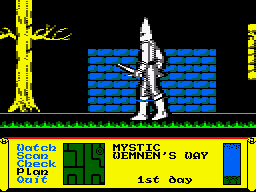

Mystic

The hooded mystics are your only magic users in the game, and losing them renders the game almost unbeatable. Petrify paralyzes enemies, curse confuses foes and forces them to wander aimlessly, charm recruits a unit, and release relieves the target of any magical afflictions. Without one to free your characters from paralysis or curses, units can become virtually useless unless you can recruit another.

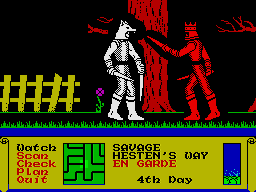

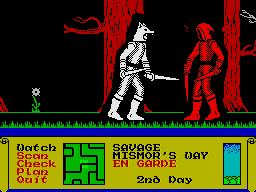

Savage

The savages are intended to be your strongest offensive unit, but they certainly don’t seem that way. Reapers and thanes can still get the best of them, and the computer mystic characters seem to target your savages more than other units. Expect your savage to get cursed within the first few minutes of play.

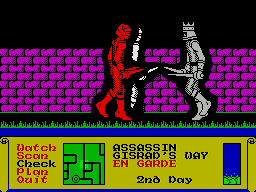

Assassin

Assassins can be formidable killers. They have a tendency to keep under enemy radar, and sending two of them after most enemy units guarantees their demise. Unfortunately, their defense is limited, and most other strong opponents can mow through them with little trouble.

Fool

Fools have a very misleading name. While they’re pretty useless in combat scenarios, they are optimal for recruitment and alliance commands. This makes them indispensable while building up your army.

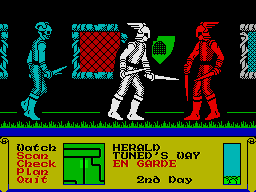

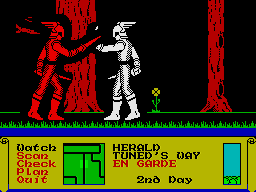

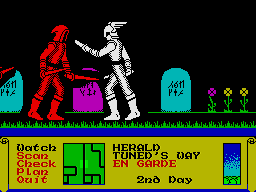

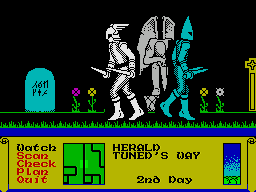

Herald

Heralds are a combination of the savage and the fool, able to fight well and persuade people to form an alliance or join your army. Unfortunately, this makes them play a very minor role in the actual game. When there are units who are great with individual skills, there’s little reason to use a jack-of-all-trades that barely specializes in any.

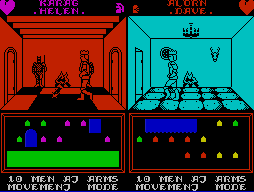

Battling your white characters are six other colored factions. The red team represents the Shadow Lords who start with the Dark Sceptre, while the green, purple, cyan, yellow, and grey characters are given spurious fantasy names. The red team has three of every main character (apart from two Heralds) and twenty Thralls, and the green faction has the same number of main characters as yours but five Thralls. All the other factions start with 10-15 units.

From the start, you can give your units three commands out of thirty-five to accomplish in consecutive order (except Thralls, they can only carry out one command at a time). When accessing the orders, gameplay freezes until one is chosen, allowing players to choose strategies carefully. Orders are simple to issue, but the learning curve is incredibly steep. The fact that most of the commands are accomplished in relation to any enemy or friendly unit literally gives you thousands of options, an intimidating predicament for any first time player. Should you insult the cyan group’s reaper, or bewitch the green group’s fool?

There’s one reason simply giving random orders won’t ever work: the massive map. The game takes place on dozens of smoothly scrolling roads which advertisements claimed equaled 4,000 individual screens. There’s only a handful of different backgrounds, including graveyards, mountainous areas, and a variety of city streets, making it easy to get lost without referencing the map. Additionally, simply issuing an order is impossible unless you can pinpoint an enemy’s location. Telling your fool to recruit the purple thane isn’t a bad idea, but they’ll simply wander aimlessly looking for their target the entire game unless the fool is directed to the thane’s location and then given the persuade or bribe order.

This makes pin-pointing enemy locations and determining the immediate surroundings crucial to success. When one of your warriors dies, you retain the ability to view the screen where they were killed, which becomes pretty useful when searching for individual enemies. If you want to accomplish anything, it’s best to have a plan of action based on observations from these vacant screens.

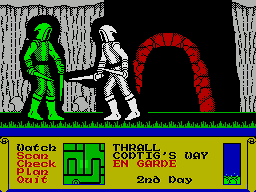

The most basic element of the game is combat. Even if you never command a unit to kill another, factions will strike up battles. Other groups will only fight you, a disadvantage that heightens Dark Sceptre‘s difficulty. Only one battle occurs at a given time, and you can immediately cut to it by pressing the watch command. Despite this, multiple battles can be queued up at any time, meaning your armies can fight four or five battles in a row. Whenever this occurs, a unit is placed “En Garde” and will not respond to any input until after their eventual battle is resolved. Many consecutive battles wouldn’t be so bad, but this situation often leads to a frequently occurring bug that where one of the combats never initiate. Saving often and reloading always curbs this issue, although it happens way more than it should.

Players can call a truce with any faction by using the befriend command on any of their units. If successful, the entire group will permanently stop their assaults. The charismatic heralds and fools are best suited for this, although failure will often leave these crucial characters in compromising positions. Having a strong character follow them is a wise move. To break off a treaty, the player must insult a member of the group. If you attack anyone you are currently allied with, the pact is broken and future befriend attempts with any group will be largely unsuccessful.

Even more important are the challenge, persuade, and bribe options, all of which recruit other factions’ units to your cause. Creating a larger entourage is the most successful strategy, dwindling your opposition and building up your army. Anyone can be recruited, although there is no guarantee of success unless certain measures are taken to build up rapport.

While you can simply give opponents stuff to make them like you, items are very difficult to find. This is where the mystics come in. If mystics petrify and curse an opponent and then charm them repeatedly, building troops only becomes a matter of patience.

Recruiting more strong units takes time, but you need them. After recruiting the strongest characters from the other factions, tackling the Lords of the Shadow still takes a lot of patience. Any decently built army will almost always yield success, but victory is only guaranteed after hours of play.

While Dark Sceptre does tend to get pretty monotonous, the excellent graphics and sound are engrossing enough to keep you involved. All characters are enormous animated sprites, a feature that few other ZX Spectrum games even attempted. Movements are incredibly smooth, recalling Tir Na Nog’s walking man, and battles are entertaining to watch thanks to the variety of attack motions. Characters will swing their swords and move away from attackers if they’re losing a battle, and it’s always satisfying to see your character get the final strike. The sounds are almost as great. During battle, the clashing swords are accompanied by clanking noises, while any character’s death lets out a cool digitized grunt. There’s also a short majestic theme that plays whenever a session starts or ends, a decent set of four channel chords that brings a lot of pomp to the game. This same theme also plays whenever an enemy is recruited, but this becomes frustrating since there’s no indication of which unit has joined you, forcing you to flip through your dozens of units to eventually find your new man. Still, everything feels very sophisticated for a simple 48K Spectrum title, and it’s clear that the extra development time was well spent.

Following it’s initial release in November 1987, Dark Sceptre was heavily touted as a masterpiece. Your Sinclair, Crash, The Games Machine, and Sinclair User all gave it strong reviews. Praising the graphics, sound, and relative ease of play, only the Crash reviewers noted the incredibly steep learning curve, but they ultimately resolved that the experience is worthwhile.

In July 1988, an Amstrad CPC port was developed by Consult Computer Systems, the same company who developed Throne of Fire. The game moves slower, the graphics look shoddier, and the sprites experience some color clash when overlapping each other. This version received very negative reviews, with Amstrad Action, Amstrad Computer User, and Computing with the Amstrad all slamming the inferior port.

Dark Sceptre is a testament to Mike Singleton’s prowess in playing with genre conventions. Despite all the initial frustrations and the general lack of direction given by the manual, everything becomes pretty clear after a handful of hours. Creating useful groups, planning ambushes, figuring out new ways to uncover enemies positions, and finding useful items are all goals that will become clear to any player after a lot of trial-and-error. While the adventure elements are limited to inventory manipulation, any player with a love for strategy games ought to at least sample Dark Sceptre. It’s slow pace and side-scrolling perspective might be totally foreign to real-time strategy veterans, but Dark Sceptre takes an interesting approach to a now worn-out genre.

No sequel to Dark Sceptre was ever planned, as Singleton shifted his focus to Eye of the Moon, the intended sequel to the first two Lords of Midnight games. He continued his experiments in real-time strategy with 1989’s War in Middle Earth. Only the ZX Spectrum version was developed by Maelstrom games, while other ports were completed by Synergistic Software. At the turn of the ’90s, Singleton took his strategy design elements and applied them to the formative first-person RPG genre, creating his highly influential Midwinter series.