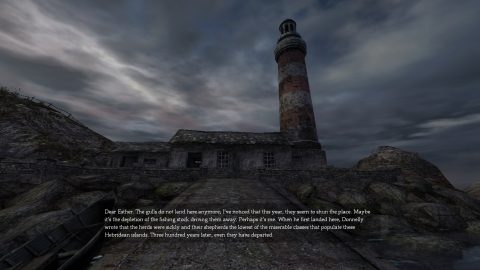

When approached as a game, Dear Esther is bundled frustration. A game all wandering around an abandoned island sounds like a great premise for exploration and wonder, but that’s not what Dear Esther is about. The first-person experience begins in front of a light house, with the adjacent hut’s door wide open. I walked up to the building burning with anticipation of ascending the tower and enjoying the view, but was soon disappointed by a broken staircase and no means around that obstacle.

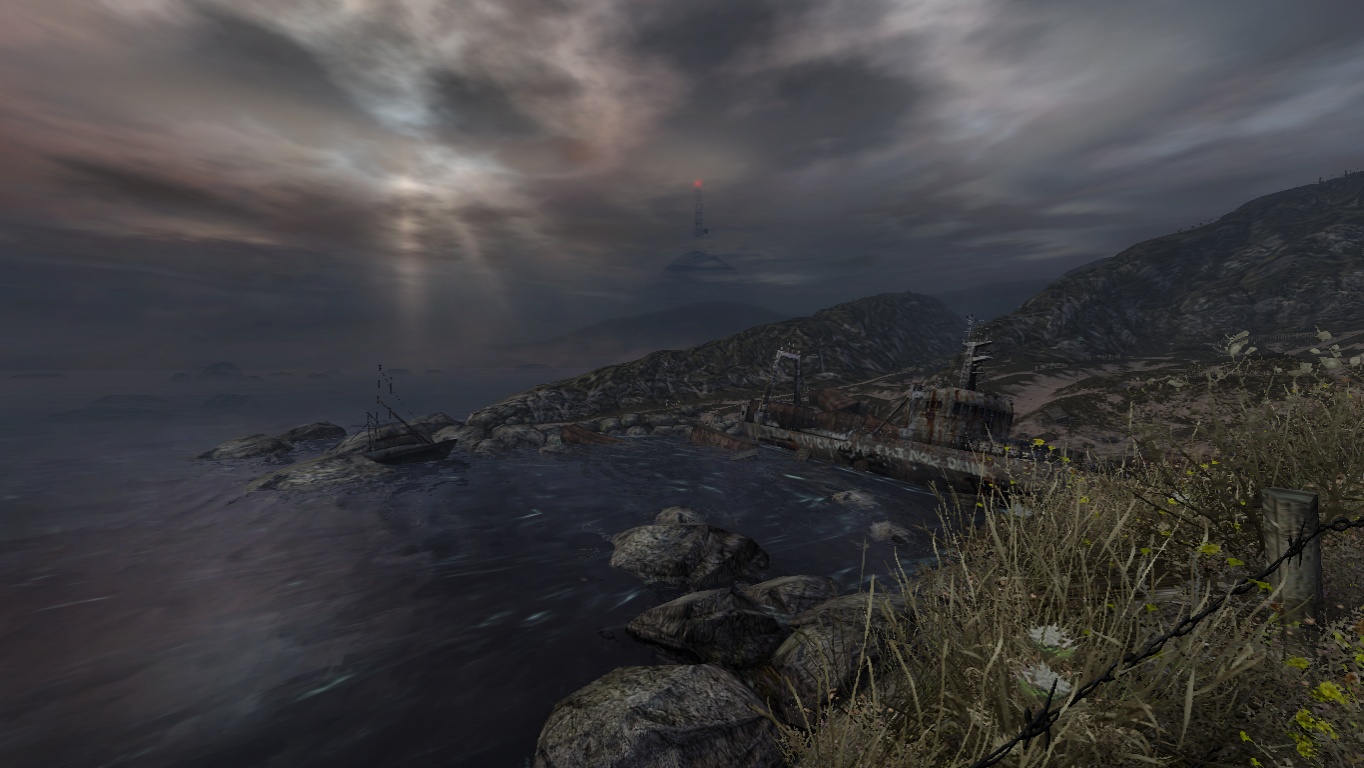

But Dear Esther is rarely even that subtle: Before long, one approaches a shipwreck at the beach, the game teasing with the words: “There must be a hole at the bottom of the boat,” but approaching it from the water is made impossible by a wall of ankle-high rocks. Dear Esther is not like a stroll over an island, it is like a guided museum tour of some historic site, no touching allowed (there are no means of interaction, no jumping and no climbing) and the most intriguing areas off limits to the public. You can go into the water, but if you try to get anywhere by swimming, the game pretends to drown you and just puts you back at the shore.

Sure, linearity makes sense in the narrative: After all, the protagonist is a broken, dying and potentially insane man, determined on his last pilgrimage, reciting notes from his journals and letters to Esther, which vaguely hint at the tragedy of his life as he goes along. The work does have merit as a media-enhanced epistolary narrative, which is skillfully told despite a somewhat cliché plot underneath, complemented by stunning environments and a dense acoustic atmosphere. Especially the stalactite caves are one of the most beautiful locations ever seen in any video game.

There is one other advantage those caves have above the other areas: The space here is believably and naturally confined, without any of the annoying fake blockades that plague the rest of the island. The lack of traces of civilization also avoids frustrated inquiries like “What’s this document I just found in this inconspicuous location?” or “I wish I could have a look in that briefcase the tide has washed onto the island.”

Ironically, the game’s technical difficulties ultimately showed me the best way to “play” it: it is, for example, easy to get stuck permanently in the scenery. The game is supposed to allow restarting at any of the four chapters once they’ve been reached, but that simply didn’t work, but the entire game is available to watch on YouTube. The fact is somewhat depressing, but this non-interactive consumption actually made the experience more enjoyable, without bumping into frustrating obstacles and the tediously slow backtracking from dead ends, which only emphasized that even the greatest audiovisual presentation cannot hide how crucial a role the smell of salty air, the feeling of the breeze and the texture of the ground underneath the feet play in making a walk on a lonely beach an inspiring experience to begin with.