Ian Livingstone is one of the biggest names in British fantasy gaming. Together with Steve Jackson, he founded Games Workshop, brought D&D to the UK and invented the Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, starting with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The most famous and successful of the books, however, was Deathtrap Dungeon.

It’s one of the most cliché fantasy adventure settings you can imagine: The sinister Baron Sukumvit annually challenges potential heroes to the Trial of Champions in his magical labyrinth beneath the city of Fang (most of the exotic names in the book are based on actual places in Thailand), the eponymous Deathtrap Dungeon. Here they have to face countless traps, monsters and other encounters, defeat a full-grown dragon in the end to survive and earn insurmountable riches and glory. Needless to say, no one ever succeeded, until the player comes along… and plays the game for dozens of times, as the game is as deadly as it sounds.

Livingstone actually made his first forays into the video game industry as early as 1984, when he wrote the story for Eureka! for Domark, the company he would later lead into the merger with Eidos, where he holds an important position to the day. So the eventual announcement of a Deathtrap Dungeon video game adaption wasn’t really surprising news. Many fellow Games Workshop designers and fantasy book writers carried out the translation from paper to polygons. Richard Halliwell, author of Warhammer and Space Hulk, was chosen as the lead game designer. Also on board was Jamie Thomson, whose fantasy game books had been adapted to microcomputer games since the ’80s, and who continues to be one of the most prolific authors in the genre.

Domark first announced Deathtrap Dungeon the video game in early 1996, around the time it started merging into Eidos Interactive. It’s hard to find any Western sources that reported on the game at first, but it was relatively prominent in Korean magazines at the time. First screenshots still showed a blond protagonist of the usual gruffy hero type, but within few months he was replaced by the hard-bitten thug called Chaindog. (Blondie still makes a cameo appearance on the PlayStation as an adventurer turned to stone by the Medusa, though.)

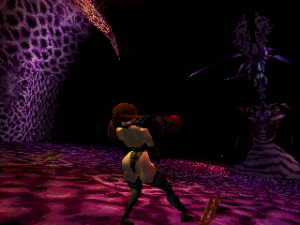

Only after the huge success of Tomb Raider people started paying attention to Eidos’ other 3D action game. Since it runs on a similar-looking 3D engine, Deathtrap Dungeon has often been dismissed as a cash-in on the success of Core’s hit franchise. This claim doesn’t quite hold water, given that the game was already in development when Lara Croft’s first adventure was still far from finished. The female protagonist on the other hand, the scantly clad assassin Red Lotus, was first introduced at a rather suspicious time in early 1997, mere months after the release of Tomb Raider. Her initial outfit included little more than a metal thong and a chain hanging around her neck to cover her nipples. Whether executive prudery prevailed in the end, or someone simply noticed how ridiculous it looked, she ended up with a somewhat more chaste leather leotard in the final game.

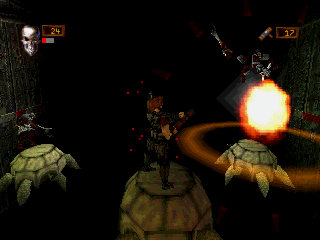

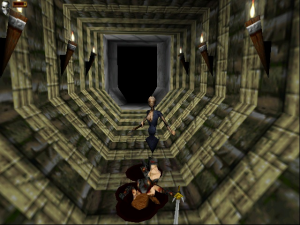

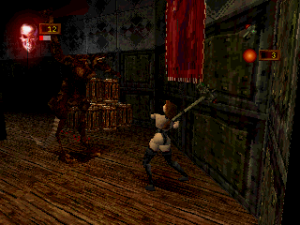

Another reason for the many comparisons to Tomb Raider are the controls, which use the same scheme with the good old tank movement. Platforming is more problematic, though, as the game has more areas with fixed camera positions, and there’s no way to do the jumps systematically like with Lara Croft. For some reason the HUD contains a speed meter, which of course is completely useless. Contrary to Tomb Raider, though, platforming plays only a minor role. The focus of the game instead lies on melee combat. The protagonists (who both play exactly the same; their differences are merely cosmetic) have three different combos (four on PlayStation) at their disposal, chosen by holding the attack button together with the directional pad.

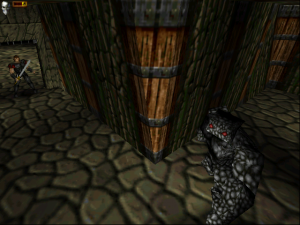

The hit detection feels a bit dubious, especially when the heroes are surrounded and keep getting hit from all directions at the same time. But there is a method to the madness, and after learning to use the different combos and – most importantly – block properly, it all starts to make sense. But that doesn’t mean to say it’s not totally brutal all the same, and the adventurers will still get eaten by dinosaurs, incinerated by dragon breath and mangled between the fist of rock golems aplenty.

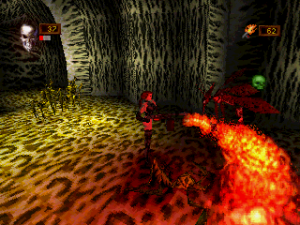

If the direct approach appears too risky, there’s a whole arsenal of projectile weapons, too. Since pretty much the same group of people is responsible for both games, there’s quite a bit of crossover with the Warhammer universe and its steampunky elements. The first firearm to find is a standard “shotgun”, or rather its ancient version, the blunderbuss. Bombs, a flamethrower, a portable mortar and even a rocket launcher (firing with fancy fireworks rockets) can later be found within the maze.

Ammunition for the firearms is limited, though. Similar goes for magical swords, which break apart with use. All of them are extremely strong, but usually facilitate the killing of certain enemy types, so the Venom Sword easily disposes of poisonous enemies, the Silver Sword is used to get rid of the undead, and so on. The only weapons to rely on at all times are the trusty old sword and a war hammer, which is so heavy that it’s hard to ever even actually swing it before getting killed.

But of course one comes to Deathtrap Dungeon to see the deathtraps, and there’s plenty of those. Expect to get roasted, shot, mashed, bombed, hacked into pieces, dropped down crumbling floors onto well made beds – made out of arm-long metal spikes – and pretty much die in all the cruel ways imaginable. The property sure earned its name. It’s not as bastardly as can be, though. Attentive adventurers can often see beforehand what’s coming for them. Nozzles in the wall and darts on the floor are there to provide hints that something’s rotten, just as much as the decaying remains of those that tried their luck before. This actually makes the game a lot fairer than the book, which often leaves the player with seemingly random choices and the anxious hope to not have picked the deadly one this time. Well, the dungeon still presents awkward dilemmas, like two-switch setups where one switch defuses a trap and the other activates it, with no tell for which is which, but an author has gotta have some fun at the cost of his victi… ehrm, audience.

If something moves and yet it doesn’t kill, chances are it’s the content of the many rotating treasure items. The loot ranges from common healing, strength and antidote potions to useful charms hat make the heroes temporarily invulnerable to magic or let them survive walking through fire. Occasionally even some gold or jewelry can be found in the depths. The riches aren’t used to secure wealth in the outside world – the reward for surviving the labyrinth should be more than enough to settle the retirement fund. Instead, some of the savepoints (both the PlayStation and PC versions use them) are glowing red, meaning their use is subject to charges. It’s also possible to enter every reached level directly, but since the dungeoneers start out devoid of any items when entering this way, it’s not recommended.

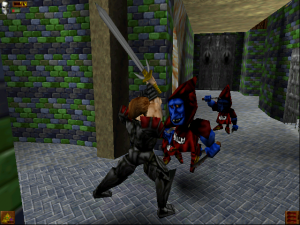

The baron’s collection of monstrosities is quite impressive. More than 40 different enemy types await, from evil juggling clowns and silly cap-wearing goblins to demon priestesses, steam-powered robot scorpions and the Warhammer ratmen – everyone who’s got a name in fantasy monstering can be found in the dungeon. Even a bunch of not-T-Rex serve as mini bosses. Just as the specimen that shocked players in Tomb Raider almost two years before, they walk freely around their area, menacing and deadly, a far cry from modern action game bosses who too bluntly betray the fact that they just now spawned for the player to fight them in their designated arena. In Deathtrap Dungeon inventive adventurers can actually turn the dungeon against their foes by luring them into traps. This, dear modern game developers, is how to design a puzzle boss.

At the end await the dragons known from the book, one bigger and deadlier than the other. This boss rush opens with the Blood Beast, one of the most iconic (and most disgusting) monsters in the dungeon, which used to decorate the cover of the original editions. Afterwards follow the three-headed Hydra, the flying dragon Vilefor and the red dragon Melkor for the final confrontation. The latter two actually dwell in huge caverns were they can fly around, harassing bypassing adventurers with explosive projectiles and their fiery breath. There is also a cool ride on the back of flying turtles over a giant pit.

Outside of these rare occasions, the architecture lacks a certain sense of grandeur that makes games like Dark Souls so compelling more than a decade later. The book could convey that using the sheer power of words, but it would have costed much additional work and budget to realize graphically in 1998. The level design is by no means bland, even though it’s mostly just rooms and corridors and pits and switches and traps and monsters. Yet it cannot but disappoint to have interesting structures like the huge buddha statue entirely missing, especially since Tomb Raiderhad set the architectural bar high with the Sphinx and its huge Midas statue. Many non-standard encounters from the book are also left out, like the skeleton on the throne, which after all was prestigious enough to eventually replace the Bloodbeast on the book covers. Players could also briefly meet and interact with several other unlucky adventurers in the book, while all that’s left of them in the game are their bones.

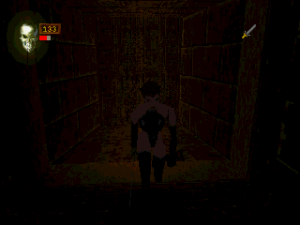

Much of the atmosphere is owed to the sound department – like in a good horror movie, effects are designed to instill paranoia and fear: Before you can even see the enemies, you hear them phasing in when they respawn, the growling of the Ogres and the creaking mechanisms of the Automata. Squeaking doors and spurting blood do the rest.

There are no uplifting rhythms or beautiful melodies to go with that, either. The beginning chambers offer no music to hear at all. Only when the monsters start attacking, the martial soundtrack first kicks in. Inside the dungeon, its all eerie screeching noises, bombastic war drums and gladiatoral fanfares. It is a very effective soundtrack in the context of the game, although it offers nothing suitable for standalone listening.

Although the game first came out for PlayStation, the primary platform for Deathtrap Dungeon was the PC, according to the in-game credits. But the PlayStation version was anything but a simple downscaled port. Naturally, it runs in low resolution and thus the texture quality isn’t as high, but it still manages to be aesthetically superior regardless. The lighting is more colorful and atmospheric, and the graphics just are on a higher artistic level than the PC textures. Those often seem too orderly and regular where the PlayStation version looks nasty, overgrown and dirty. The drawing distance is a bit shorter on the console, but the increased darkness only adds to the atmosphere.

Deathtrap Dungeon‘s PC version has one really cool feature that got dropped in the conversion: All the damage the adventurers take shows on their bodies. As they take more and more abuse, all their bruises and cuts are clearly visible. Even arrows keep sticking in their flesh until healed. After a certain amount of damage, it almost hurts just to look at them.

But the two versions don’t only differ on an aesthetic level. The PlayStation game is more akin to a remix, with different enemy placement, changed loot and sometimes different secret areas. The level architecture is usually similar, but rarely quite the same, and at one or two points it just takes the same setpieces to build a completely different challenge. The most sensible change is the addition of a backwards strike for the sword. On the PC the only means of defense against attacks from behind is slowly turning around while blocking, which is more than just a little awkward, especially when you’re surrounded by multiple enemies.

Due to memory constraints, the areas are also broken up into smaller portions, while some are switched around in order. One level, the Quarry, got excised entirely from the port, but seeing how it hosts the most annoying enemies, aggravating platforming passages and a really stupid puzzle, it’s almost safe to assume that this was a conscious decision rather than a cut for space. Only the loss of some cinematic moments is a shame, especially the hub area for the final boss fights, where each door is guarded by a dragon statue that comes to life after you’ve killed the previous dragon. The multiplayer deathmatch mode is also missing from the port.

Deathtrap Dungeon was optimized for Windows 95/98, so on more recent systems the original CD release has a number of issues. For one, the multiplayer mode doesn’t work at all. The same goes for sound and music; the game is now completely mute. So except for those who still got a running ’90s PC around, it’s better to get the digital download release on GOG.com or Steam, which fixes these issues and comes with a built-in Glide wrapper to support the 3DFX card capabilities.

For collectors, on the other hand, the original PC release is the most interesting thanks to the Premier Collection, which contains a Deathtrap Dungeon card game and an edition of the original gamebook. The Bestiary, a booklet that came packed with all versions (at least for the UK release) and describes the various creatures inside the dungeon, is also expanded with profiles of the protagonists and an additional world introduction for PC gamers.

Illustrations from the Bestiary.

Deathtrap Dungeon suffers from the same trappings as most 3rd person action adventures of its time; first and foremost the awkward and unprecise controls and camera issues. Even back in the day it wasn’t received as well mostly because it was perceived as “that Tomb Raider cash-in game” and because of the harsh difficulty. But it is that brutality that gives the game its identity. At times it almost feels like an early specimen of those sadist games specifically designed for the player to be tortured, and like it. Except it’s not as slickly designed.

In fact, it’s hard to miss several seams at the edges of mechanics that are implemented, but not at all fleshed out. So the adventurers get a piece of chalk to make markings on the floor, yet none of the stages are labyrinthine enough to warrant the effort. Both protagonists can also use their fists in hand-to-hand combat, but they never lose their standard sword, which is always superior, rendering the unarmed variant completely useless.

Regardless, Ian Livingstone’s Deathtrap Dungeon is a rough diamond of an action game that begs the question of what might have happened if it had been followed by more Fighting Fantasy adaptions. But seeing how Deathtrap Dungeon didn’t leave much of an impact and the Fighting Fantasy guys had already blown their ammunition by adapting the most popular of the books, it’s not too surprising that there were none.

Only in 2003, Taito implemented a few Fighting Fantasy books for Japanese mobile phones, starting with The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. That book was also adapted as an ill-received first-person DS game more than a decade after Eidos’ Deathtrap Dungeon, the only other time someone attempted something more than a straight digital port of Fighting Fantasy. Some of the books, including Deathtrap Dungeon are also available as iPhone apps. These are direct implementations of the original books, which merely add a fancy wallpaper and some colored illustrations.

The Deathtrap Dungeon iOS app.