For some games it would seem as if destiny itself was working to bring about failure, as if nothing, not even excellence, could have saved them from bargain bins and commercial obscurity. The Divide: Enemies Within (hereafter referred to as Divide) was such a game, plagued with problems from the very beginning of its rocky development, ultimately ignored by critics and consumers alike and yet somehow among all this managing to be, not only a fantastic PSOne game but also a damn fine homage to Nintendo’s Super Metroid.

Problems started when Radical Entertainment sought a publisher – each time they found one it was bought out, leaving them hanging. When The Divide finally came to market it was very late, sneaking into American stores on the tail end of 1996. The unintuitive name resulted in incorrect listings, while most magazines only got around to reviewing it in early 1997. Their biggest criticism along with average scores? That it was too 16-bit in terms of design and too much like a last generation title. It was almost universally avoided.

Now, it must be asked, what the hell does “too 16-bit” even mean? The game features a complex control scheme utilizing every button on the pad, various multi-use items and weapons, and a gradually expanding area of exploration. By all accounts the gameplay was substantial. Neither could it have been a result of everyone’s obsession with the third dimension and shunning of things 2D – Divide implemented 3D with great panache and took advantage of what was possible. In all likelihood the comments probably arose because of its startling similarity to the SNES classic Super Metroid, in terms of atmosphere and design. The cliché of familiarity breeding contempt suddenly seems apt. Its greatest blessing became its ultimate flaw – a simple case of bad timing, being released long before the term “Metroidvania” came into vogue and people started clamoring for all and any such titles available.

The Divide works on two different levels; it has a complicated well written plot coupled with incredible atmosphere, which is then backed up by solid and well designed gameplay. The game starts after a rousing written account detailing the main characters, Tanken and Advina, both of whom are mercenaries protecting a ship of sentient AI refugees which are escaping a planet in the throes of a Luddite-styled revolution – Tanken’s motives being to break away from the ways of the mysterious old order. None of the technicalities are explained and much is left to the imagination, meaning the story doesn’t run the risk of feeling overworked. A respectable looking FMV introduces their vessel drifting through space, with all passengers in hibernation, as it searches for a suitable new home world. An uninhabitable frozen planet is discovered, but maybe the gaping fissure on its surface can support life, and so ten automated probes are dispatched.

It is here things go awry when one probe crushes and kills the mate of an indigenous creature, while the radiation from them grants sentiency to all nearby life. Tanken and Advina are awoken from cryosleep hibernation and board their enormous Terragator units (giant walking mechas), before heading down into The Divide. The enraged creature attacks and immobilizes them, before carrying Advina off. Tanken remains and is again plunged into hibernation when his heating unit fails. Over an unknown period of time The Divide thaws out and Tanken eventually regains consciousness, his Terragator unit being badly damaged (with all items having been stolen) and barely operable, at which point the player takes control. The time spent laying there is never disclosed, but by the look of how drastically everything has changed, the implication is millennia. Advina is likely dead and you are now stranded with no hope of return. While the game contains no further narrative moments until the end, this technique of alienating and inducing a sense of loneliness in the player makes each discovery and step of exploration feel like the reading of another’s diary. Why were the once docile creatures suddenly driven to create huge eerie structures throughout their world? Why had they taken and hidden various pieces of equipment? What exactly had the launching of those probes set in motion and what can the ultimate conclusion to this quest for survival be?

The game’s basic structure is that of a guerrilla war, slowly acquiring items and weapons until you’re powerful enough to actually reach and engage in the final confrontation. Each additional munitions pack makes you stronger, while the enemy gets weaker. The pacing of these items is implemented in a way to encourage exploration and give players a sense of real achievement. From the opening the Terragator unit is limping, but less than a minute later a repair kit is found and normal walking is restored. Progress can’t continue until this item is collected, but overall it adds nothing to the sequence of gameplay events. It’s one of many superfluous little touches which builds atmosphere and sets up the nature of things ahead; progress is halted or staggered until the needed items are acquired.

Weapons are suitably powerful and diverse, comprised of screen-filling Power Bombs, standard Missiles, Homing Missiles, a Gattling Cannon, Flame Laser and Particle Blaster. For each of these there were five ammo canisters to be found. There are also energy tanks to collect – making methodical exploration of each area worthwhile. There’s also a degree of non-linearity to exploration, and by the time you acquire the Double Jumper no area should be beyond reach.

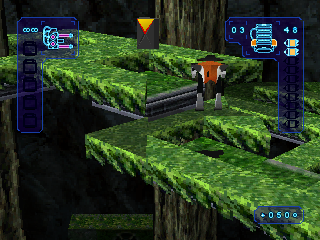

The graphics make good use of 3D, with hidden passages and areas. These never frustrate though, due to the cleverly implemented map screen. It works elegantly, as all map screens should, and makes the viewing of whole areas easy. Great for noting points of interest that later need exploring. Rather than attempting a fully freeform camera, the game has a fixed camera which can be panned up and down. In conjunction with the map screens, this ensures you are never lost, and are never without an idea of where to go next. It also makes the 3D platforming sections as painless as possible, with only one notable section in the Lava Rift area proving frustrating.

Considering how many other games omit even the simplest of things, it’s refreshing to find that the designers have taken into account what normally frustrates gamers. For example, while there are lengthy jumping sections in the slippery Ice Chasms, the actual platforms you are jumping onto have barriers at their sides to stop you falling off. Again, it’s these small touches which show that while the team were trying to come close to replicating Super Metroid‘s design structure, they also had an understanding of what wouldn’t work. This helps to make the adventure very satisfying.

There were many magical moments where it hits you just how inspired by Metroid things are. Cynics may call it plagiarism and unoriginal, but we say it’s the sincerest form of flattery. There are Power Bombs, Missiles and 99 unit Energy Tanks that resonate with a familiar chime when collected, not to mention an expanding map, several elevators, and similar music.

Those expecting a lengthy and silky smooth 60-frames-per-second adventure might be disappointed at the frame rate and slightly short length (around 5 hours, despite two endings), but this doesn’t detract from what is an otherwise excellent game, and one which invokes nostalgic recollections of a genuine classic. At its core it may have been an imitation, but when you’re imitating the best it’s inevitable that some of the original quality will pass along.

Other versions of The Divide: Enemies Within were developed by Radical Entertainment. One which saw release was a PC version, receiving even less fanfare than the PSOne game. Reviewers of the day were especially harsh, flaying it raw for having pre-set save areas as opposed to quick-saving. Needing a Windows 95 based Pentium PC with 133Mhz and 16Mb RAM, this might be a cheaper option for some, and at the very least an interesting curio to own.

Characters

Skrit

Found in the opening area, these creatures shoot you with the cannons on their backs and are fast, but not too powerful.

Kimph

Harmless when there’s one in the sky, but dangerous when they attack in groups. Make good use of strafing to take them out with missiles and gattling cannon fire.

Forest Mole

Dozy creatures which dash to attack when they spot. Stay out of their sight and pick ’em off from a distance.

Dozer

Slow but powerful creatures found in the Floating City. So long as you don’t fall into the rivers of acid you should be fine.

Kritah

Spiked insects from the Ice Chasm, which don’t pose much of a threat.

Weapons

Some of the main weapons at your disposal. Despite the variety, you’re seldom in a situation, apart from bosses, that requires their use.

Gattling Cannon

Like a machinegun, this fires quickly and has a long range, and is the first major weapon you find. Although the standard blaster works for most enemies, this is great for taking down bosses quickly.

Rockets

Extremely powerful, but line of sight only, making them difficult to aim. If the enemy is slow or immobile (such as some bosses), this perfect for dealing massive damage to their weak points.

Flame Laser

Fancy name but it’s really just a flamethrower. By the time you get this you’ll be adept enough with the controls to just rely on the other weapons, only pulling this out when you’ve no more ammo. Can damage multiple enemies.

Particle Blaster

Basically a shotgun with a wide radius of attack. Slow firing and mostly useless unless everything else is out of ammo, or you’re fighting the skinny droids in the Floating City.

Homing Missile

The best weapon in the game. Huge damage and it homes in on the nearest enemy, allowing you to fire while running away. Ammo is scarce, so use very sparingly.

Power Bomb

Just like the Power Bombs in Super Metroid, when these detonate everything on screen except the player is damaged.

Quick Info:

|

Developer: |

|

|

Publisher: |

|

|

Genre: |

|

|

Themes: |

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

The Divide: Enemies Within (PlayStation)

Items

Just like Super Metroid, there are many items that power you up and enable further progress. Some important ones:

Repair Kit

The game starts with your Terragator unit limping due to damage. Find this to enable normal walking.

Terrain Mapper

This handy item maps where you’ve already been in the game, displaying it as a moveable blue polygon display. Later map enhancers will reveal hidden areas.

Jumper Unit

Until you’ve found the jumper unit, even small obstacles stop you. Later on you’re able to double jump.

Transporter Key

This key activates the dormant transporter system. But who built it, and for what reasons?

Heating Unit

Essential for the Ice Chasms, this keeps the joints defrosted and seats toasty warm. No word on whether it makes a cup of tea though. There is also a cooling unit for the desert area.

Armour

There are two armour upgrades: the first in crimson is found in the Ice Chasms, the second in blue is found in the Sky City.

Areas

The Divide’s organic environments are varied and hostile…

Planet Surface

Welcome to hell – malfunctioning, desperate, alone, and stranded on a desolate Planet Surface. Cold walls of crude concrete haphazardly criss-crossed with pipes greet you, while the background music is eerily similar to Maridia and Brinstar themes.

Forest Canyon

There’s constant rain as lightning blisters the sky above, and enemies home in on you. The forest contains many essential items, but you’ll have the navigate the maze of branches found high above.

Jungle Gorge

Strange and decayed ruins cover the landscape, created by civilisations that don’t exist – except in the depraved nightmares of the possessed creatures wandering throughout. Amid the vine covered pillars, beware of crumbling platforms.

Ice Chasms

In freezing temperatures far too low for even machines like the Terregator unity, there manages to survive a great many evils. To succeed against them you will need the heating unit, but who knows where it lies?

Desert Arroyo

The searing wastes of the Arroyo desert is home to unnatural forms of organic and machine transmutations. The temperature reaches 200 degrees Celsius, making the cooling unit essential for survival.

Lava Rift

Rivers of lava flow beneath an industrialised playground of metal spires and platforms – the enemies are immune to the molten slag but you are not, so avoid falling in. Down below, beneath the behemoth structures, lies in await both an enemy and old friend.

Bosses

The bosses were all once harmless foragers, now mutated over the millennia by the probes’ radiation. Here’s a selection, with their descriptions from the manual:

Moropus – The Clawed Bearhorse

As the first hideously deformed guardian, Moropus guards the Jumper which frees you from the confines of ground level. Fast strafing makes short work of him.

Papilion – The Bad Seed

Arguably the toughest boss, simply by virtue of you still being underpowered. A freakish hybrid of plant and insect, Papillion takes two forms: first a pod firing deadly seeds, followed by a hatched larva with missiles. Keep jumping!

GianWhu – The Crabby Assassin

By now you should have the Ice Grippers, which thankfully restore standard walking. Ignore his formidable size, GianWhu is slow and poorly mobile – just make sure to avoid his powerful attacks.

Gastro – The Lizard King

This multi-tailed serpent lives in the side of a giant mountain, occasionally poking out to attack you. Make use of diagonal firing and the available platforms. Don’t fall down the ravine just below him!

Interview with Ian Verchere, Designer for The Divide:

JS: Tell us about the Metroid inspiration. How did the original pitch come about?

IV: In pitching game ideas to potential publishing partners, or upstream within an organization, the trend has been to try to reduce the concept to a log-line or elevator pitch. I’ve got mixed feelings about this; on one hand I appreciate the simplicity and effectiveness of messaging and communicating a vision to the development team and to senior executives who likely don’t play games anymore. On the other hand, we’re game makers, not movie producers, and so it’s not as simple as combining two elements to create a log line, such as “Die Hard on a bus!”? (the pitch for the movie Speed). Our experiences are interactive and ultimately depend on the relationship between the player and the character on screen.

What I am saying is that a “playable” has to be the cost of entry now, not a pitch. The best way I can support this is asking you to imagine this exercise: go in to a modern console publisher now with this pitch:

“It’s about two plumbers from Brooklyn who travel through plumbing to weird worlds and eat mushrooms to give them special powers and abilities.”

I had put my career at Radical Entertainment on the line by insisting we go ahead with a Beavis and Butthead game (for the Genesis). Nobody understood the license at the time, and even MTV was thinking shooter/platform. The President of Radical said if this thing went over-budget or schedule he’d fire me. Senior management then had no time for “action” games really; it was all about taking on EA Sports.

I mapped out a design that was essentially an RPG, and even though I’m a Nintendo fan-boy at heart, thought that the perception of the Sega Genesis as a slightly “older” platform was the way to go. The game was a hit, and went on to be a very successful franchise for Viacom New Media.

My favorite games have always been Nintendo softs, and Super Metroid for the SNES was at the time, for me, a perfect combination of adventure, shooting and platform. I learned a tremendous amount about level building, expanding maps and reward vs. challenge from extensively playing that game, and finding common Nintendo design elements with The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past.

So, leveraging the success of Beavis and Butthead, and supported by technical demonstrations of a strong in-house 3D engine, I came up with the idea of trying to make a Metroid experience on PlayStation and pitched it successfully to Viacom New Media as “Super Metroid in 3D!”?

Working with some great people, including most of the folks who went on to form Relic and build (the PC RTS) Homeworld, we were able to get a development deal to create an original IP for PlayStation. That’s quite something, and I’m proud of that to this day.

As for goals, we wanted originally to get Æon Flux, and applied the same design goals that shaped The Divide to that license. I had in mind the same thing that Core ultimately achieved with Tomb Raider; a hot female character moving through a space, viewed from behind. However, that license deal never worked out. It’s unfortunate, because we would have been the first hot chick in 3D action-adventure game.

I’d like to note as well that the original name for The Divide was Rift. I still prefer the original name, and the whole thing around the name The Divide came from marketing. It was never a game about kidnapping and revenge, but that’s what some of the marketing materials suggested: “They kidnapped your partner, now it’s payback time.”

JS: There was a PSOne and PC version, and I’ve heard rumours of a Sega Saturn version. Is this true?

IV: No, there was never a Sega Saturn version.

JS: Tell us about some of the difficulties involved with The Divide.

IV: Viacom New Media, the publisher, went under the day the game was to ship. That’s about as difficult as it gets.

I covered some of that in my long answer to the first question, but one of the main difficulties was pushing internally for development tools to be made. You have to understand that these were relatively early days in game development, and little adoption of software engineering best-practices were made. Hard-coding, all-nighters, transitioning from assembly to C++ and other concerns were standard operating procedure at the time.

It’s weird to say this now, but a level-editor and camera tools were seen as luxuries. Why would a producer need these things? What was fortunate was I was able to lay out the value of having a design and production team work on the qualitative experience of the game without having to get programmers to stop what they were doing, enter in variables or new geometry, and rebuild the game. Once they saw that the evil producers and lame artists weren’t bugging them anymore, they were happy to bang out some “tools” for us.

There were some brilliant people on that team: the late Martin Sykes built a 3D editor to my specifications called the New World Orderer. He and many others on the team went on to form Black Box. Jack Yee programmed a camera tool that we developed over time for Jackie Chan and had features that 6 years later, found there way into SSX Tricky and STILL felt ground-breaking. Aaron Kambietz, who went on to found Relic Entertainment with others, was the lead artist. His character design work, storyboards etc were outstanding, and he continues to this day to be a world-class concept artist.

There are others I’m forgetting for sure, but considering how under-funded we were, and how Radical executives were focused on making sports games, the people on that team seemed to thrive on the challenges we faced.

JS: Was anything planned but had to be cut from the final version?

IV: We had such an aggressive schedule, limited budget, new technology etc. that there was no cutting room floor. There’s only one Easter Egg I had time to place, and that is a hidden room with a monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey in it, and the music changes to Stauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra”.

JS: The music was very ambient, can you tell us anything about its creation?

IV: The music is something I’m particularly happy with. The theme for the opening CG movie was written and performed by Barry Taylor, a Vancouver punk rock legend.

We also pioneered (internally at least) with programmers/composers Paul Wilkinson, Marc Baril and Paul Ruskay a way to add geometry to the world-builder that linked to sound, and to actually create an interactive soundscape. This meant that sounds got louder as you approached something, and quieter as you moved away. Not a big deal now, but at the time it was pretty innovative stuff.

JS: Did you have plans/ideas for a sequel if the first one sold well enough?

IV: One always hopes that something is successful enough to spawn sequels or builds a franchise. Certainly amortizing all the tools and technology across multiple iterations makes business sense. Much of what was learned and developed went into a Jackie Chan game, but that game is a different story.

JS: Is there anything you were displeased about in the final version?

IV: Displeased? Only that I wish I had more time with the completed authoring tools to play the game through and tune it, and for the programmers to have had some more time to do nothing but work on the frame-rate. Only insiders or hardcore fans will really understand the following, but it was a huge impact on frame-rate, and it always bothered me that some initial reviews were critical of this.

The PSOne did not have a Z-buffer, and in fact was only a 3×3 transformation. This meant that you had to use A LOT of polygons to prevent floors from clipping and to sort things in front or behind each other. We had to use the Painter’s Algorithm, or priority fill, which is a simple solution to visibility in 3D graphics, but still processor-intensive in those days. The beauty of a 4×4 transformation, like the N64, and a hardware Z-buffer, is that you can use one polygon and stretch it way out, and objects sort properly. The optimizations in the Sony library were such that a polygon would stop drawing itself once camera frustum reached the center-point of the polygon. This meant that any long geometry would simply disappear. So, you had to make polygons that were small enough to stay in view, and this added SO much processing over-head. And of course, you had to have a look-up table that determined which polygon goes in front of the other. That ate up CPU cycles of course.

JS: PSOne games are being rereleased on the PS3 via download on the PlayStation Network. Who owns the rights to The Divide and would be able to make a decision on re-releasing it?

IV: That is a good question. I reckon they’re with Viacom or MTV Games somehow.

JS: Please feel to add anything else.

IV: First of all, thank you for your interest in The Divide: Enemies Within. It’s one of those titles that was a bit ahead of itself I’m afraid, but I appreciate that there are people like yourself out there now that can see what we were trying to achieve in context to the time and state of the art.