DmC: Devil May Cry was announced in 2010, and when its first trailer hit, the fanbase became very, very angry. It wasn’t just that Dante’s hair wasn’t white anymore, but more that the character presented didn’t look or feel like Dante at all. He was angry and violent instead of a confident goof, and the trailer ended with him smoking, probably the last thing the original Dante would ever do. Capcom encouraged this after Ninja Theory first presented more traditional designs, wanting DmC to be as different from the rest of the series as possible to get those sweet western market dollars, and that initial reaction resulted in a lot of reeling in on their end. That could have been the end of the circus, but Ninja Theory staff kept talking and openly insulting the old series in outlandish ways, and just about every new interview resulted in even more anger, and more backlash against the fandom backlash. Things eventually ballooned to a point that it seemed like parties who didn’t care about this game or the old DMC games at all were making completely different points only tangentially related.

Ultimately, all of this bickering and egotistical grandstanding resulted in just about nothing but making everyone look like complete fools. DmC came out, sold about as well as most of the rest of the DMC series, but didn’t ship the two million units by the end of Capcom’s financial year (it moved about 1.2 million) and that pretty much spelled the end for this experiment. The game that resulted from Capcom’s pushing, Ninja Theory’s ideas and development, and Itsuno’s guidance, despite all the drama around it, is quite good and a worthy entry in the series in its own strange way, though not without its own issues.

Things are switched up as the first game’s big bad, Mundus, is first presented as a demon disguised as a businessman who rules the human world through debt, becoming disturbed as he somehow senses the son of his old enemy Sparda, still living within his city. We then meet Dante, picking up two strippers at a club and having an off screen threesome with both in his trailer before he’s dragged into Limbo and forced to fight demons for a way out. He’s helped out by a human wicken and psychic named Kat, who introduces him to a revolutionary group called The Order and his long lost brother Vergil. Dante then remembers his past in full and joins the group to take down Mundus, which ends up being a far more complicated goal than he was expecting.

Despite the shocking idea of Dante actually having sex, the basic story and universe cemented here is a good one and serves to move the game along well, even managing to work in themes and ideas the original series never really tried before, at least in a serious way. Amusingly, the game does take heavily from all across the series and twists around a lot of basic ideas, like Mundus being a corporate villain ala the villain of DMC2, but having him already be a god of evil instead of wanting such power. The commentary the game tries to make doesn’t really succeed much, though, with Antoniades’ script being far too base or falling into unintentional ideas, like the whole demons running the world via capitalism being eerily similar to actual antisemitic conspiracy theories on a subtextual level, plus it reads as “WAKE UP SHEEPLE” most of the rest of the time. There’s a ton of references and allusions to all sorts of famous works, including Alice in Wonderland and the paintings of Baroque artist Carravagaio, but it doesn’t really add up to much, and instantly gets overshadowed by the team clearly just directly stealing the slurm plot from Futurama or having an America’s Got Talent gag in the official font. The game can’t quite decide if it’s a serious drama about the sins of fathers and sons, or if it’s a tongue in cheek satire about the late-capitalist hellscape that is modern America.

The latter fairs better than the former, especially with Dante’s characterization. The idea of making Dante out as some hyper cool anarchist punk who has sex all the time is quickly tossed aside and goes in the opposite extreme, painting him as a dumb kid who has no idea what he’s doing and just punches his problems until they go away. There’s an actual scene that ends up a close up of his face, completely dumbfounded after being asked a simple question he should have thought about at the start of the game. It’s actually endearing, and it makes his character arc work. What was sold in all the advertising isn’t actually this game’s Dante, but his persona he puts on defensively, and when it’s stripped away by the end of the game, he’s a genuinely likable and complex character. He’s the western version of Dante, trading out his nihilistic wackiness for passion and punny wit (with varying degrees of success), and it’s sold pretty well by game’s end.

On the downside, there’s an inherent misogyny on display here that wasn’t nearly as bad as the original series, made more frustrating by Ninja Theory seemingly trying to avoid the old series’ misogynist tropes and character design. Kat is a solid character on her own, but she’s not really given agency for most of the game, instead just worshipping Dante and Vergil as heroes. There is payoff later, but less so for her and more for the drama with Dante and Vergil. She also gets damseled about halfway through, even getting shot and beat so you feel really bad for her in one of the laziest writing tricks in the book. The few times Dante’s sexual escapades are brought up also severely annoy, as it paints in some really nasty toxic masculinity that presents sexual conquest as a cool ideal, which goes majorly at odds at where his character ends up and the game’s very loud anti-capitalist politics. There’s also little necessary definition given to several characters and the world around them, especially what makes Sparda such a big deal and what his goals even were, making other events lose impact because not everything quite lines up. Vergil gets it worst, because the note they end on him with is a good twist of the OG Vergil’s obsession with power, but his motivation is poorly explained.

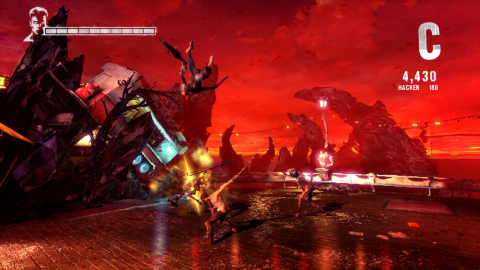

The actual gameplay is a solid answer to how to make the series more approachable for non-fans. DmC feels very different at first, lacking a lock-on and having a dedicated launcher button instead of having you do a motion alongside the melee button, but it quickly grows on you and works great with the design here. Enemies circle around you and often form packs, resulting in a mix of DMC styling and God of War crowd control. It feels elegant, and it gets more interesting when the demon and angel modes are introduced, letting you enter a different weapon set with a simple button hold down for fast switching, a solid change up from the three switching motions that also allows for some elegant platforming challenges.

Demon and angel modes also change the gun button to a sort of hook shot, demon mode using it to pull and angel to pull you towards something, similar to Nero’s devil bringer. While this has plenty of purpose in combat, it also allows for well designed platforming bits, where red and blue markers highlight what sort of pull you need to continue on. It’s a solid way to let the player breathe between combat segments, though they don’t really stick out strongly on their own. It’s mainly a way to keep traversal interesting in its own way and keep a flow to every mission, and in that respect, they work.

Those markers even help draw your eye to secrets hidden in the level, which now thankfully replace orb gathering with level completion, including finding all keys, lost souls, and completing all locked door secret missions you unlock via keys. Also, once a mission’s secrets have been sussed out, that score multiplyer for completion remains high every time, so you can focus on going through missions fast and stylishly on replay. Proud souls have also been replaced with a vague experience and skill points system, which functions pretty much the same, but removing the need to follow numbers.

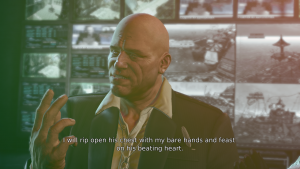

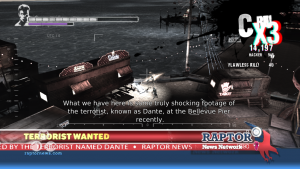

The game feels like a proper DMC experience on its hard mode, equal to the difficulty of normal for the older games, but the enemies remain pretty disappointing the whole game. Actual demon designs are pretty vague mannequin/statue things that have weapons, rarely giving an enemy that instantly captures your attention and has a unique form of attack. There are more that buff other enemies, but they prove to be more obnoxious than anything else. The one truly great enemies are the late game introduction of the Dreamrunner and Drekavac, sword using weirdos that require careful parry and counters to damage them. They’re a challenge to fight, and really stick in your mind after. The bosses are a more mixed experience, with the most visually stunning being the least interesting to fight, especially the brilliant looking Bob Barbas becoming a sort of redux of of the Leviathan Heart from DMC3, one of the game’s weaker fights.

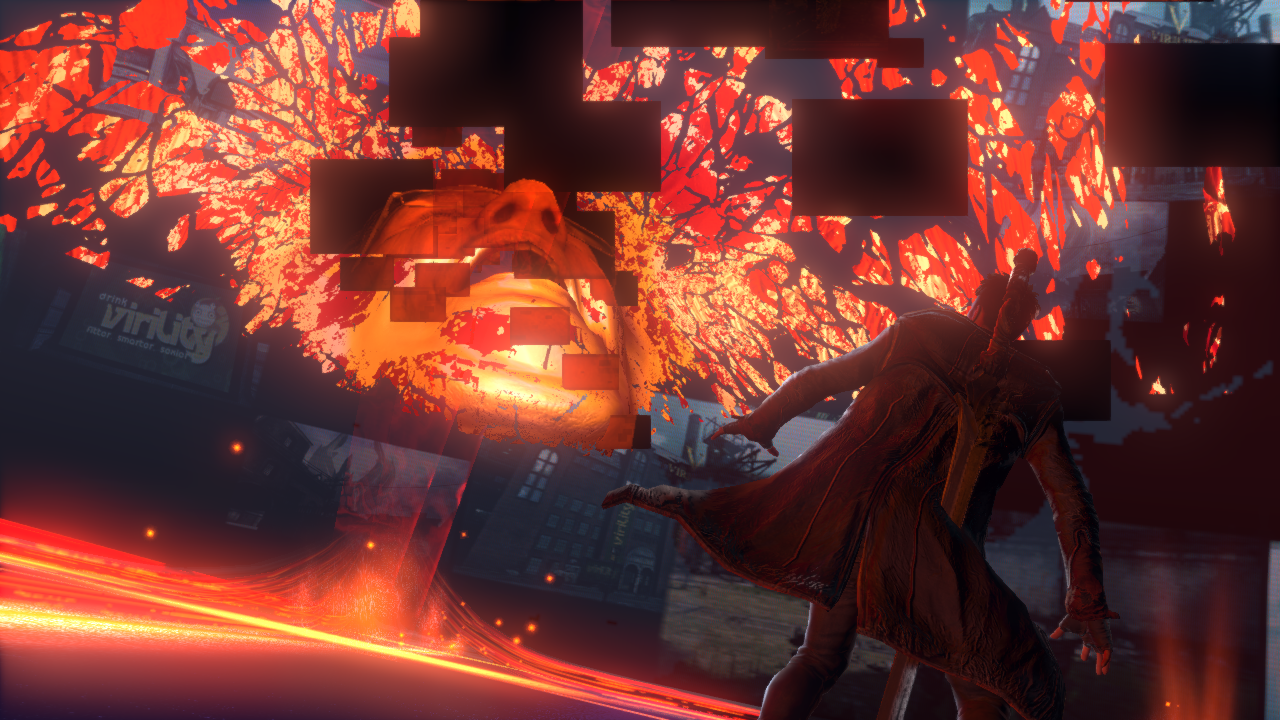

The one area the game completely outshines the original series in is presentation. The art and environment design team went overboard here, creating some of the coolest looking moments in you’ll ever see from a game, including an upside down bridge and prison, a living collage of digital pictures, a rave themed hellscape, walls closing in on you, and all sorts of other wild stuff. The game arguably has too many set-pieces to the point it becomes numbing, but it’s hard not to be impressed by the craft. The music is also good once you turn down the sound effect volume so it doesn’t drown out the tunes. Noisia’s dubstep tracks are all great and creating atmosphere, especially during the Bob Barbas and Mundus fights, while Combichrist’s lyrical tracks pump the blood at fit in well with the “hell punk” style the game is going for. Few pieces stick with you, but the few that do really do, particularly Empty and What The Fuck is Wrong With You.

If you’re still interested in DmC, you may want to try the Definitive Edition released for PS4 and Xbox One. There are a few changes to cutscenes, additional ones to address some narrative issues (though only a few minor ones), and a mess of mechanical changes inspired by the PC modding community, including the addition of lock-on. A full list of changes can be found here. Just be warned no matter what version you get, the sequel DLC, Vergil’s Downfall, is a poorly designed mess with some good ideas ruined by budget cutting and confusing level design. It’s also important to note that the PS3 and Xbox 360 versions only run at 30 FPS, a huge downgrade from the 60 FPS of the previous releases. The PC version, as well as the Definitive Edition on both consoles, run at 60 FPS, making those versions infinitely preferable for that reason alone.

DmC‘s odd place in the series is debatable, but what can’t be debated is that it has impacted the series foundations, with various ideas and design styles being used in Devil May Cry 5. It ended up being an important release, and a darn good game in its own right, the flaws never bad enough to drag it down too much compared to the any game in the main series (outside DMC3, which is in a league of its own). Capcom and Ninja Theory parted ways, but that may have been best for both groups, as Capcom now understood what Devil May Cry should be, and Ninja Theory decided to forego doings with major publishers and try their own independent release with Hellblade: Setsuna’s Sacrifice, a major sleeper hit in its own right. DmC ended up being a growth point for two different groups of talented developers, and it had a net positive for everyone involved, even if it took quite awhile to see the fruits of their labor.