Being in charge of making a sequel to a hit game does not seem like an enviable task. Change too much and you’ve alienated your audience or bastardized the game in their eyes. Change too little and you’ve squandered the game’s potential. Finding the right balance is a nuanced feat and an art of video game craft unto itself, and a great deal of games have suffered greatly for not tweaking things properly. Every now and then, though, a sequel comes along and not only demonstrates the same sense of mastery that the first game did, but improves upon it in every facet, creating something superior even without having the advantage of that sense of innovation and breakthrough the first game had.

Diddy’s Kong Quest represents this elusive ideal incarnate.

DKC2 doesn’t reinvent the platformer as we know it. The basics of the game are essentially the same, except Diddy Kong, the sidekick of the previous game, now takes the starring role, and his female friend, Dixie Kong, tags along as the parner. Diddy can cartwheel, moves faster and can jump slightly higher. Dixie can spin her ponytail like a helicopter in mid-air, easing the speed of her descent. Each character has a different victory dance at the end of each stage, with Diddy hauling out a boombox and Dixie wailing on a guitar, which are some nice touches.

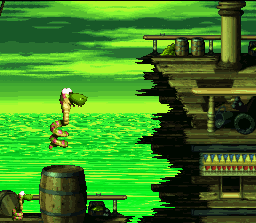

At its core, it is built quite clearly with the skeleton of its predecessor, but on top of that is a much thicker layer of muscles for it to flex in every single element of its design, from its mechanics to its aesthetics. While essentially utilizing the same engine, it sufficiently makes DKC look like an awkward and unfinished experiment.

So how exactly does DKC2 surmount DKC so unquestionably? It starts with its atmosphere. DKC begins with a thinly veiled message of youth in revolt against the un-hip-ness of old age, a funky tune, a dancing gorilla in shades, and an exploding boom box. DKC2 begins with a cascade of sparkling treasure, a pirate ship leaving DK Island behind, and the first few ominous drum beats of the map’s march. From the moment the introductory screen fires up, you know well that this game isn’t concerned with being cool or hip to the trends of the era, but is much more preoccupied with being epic, and it feels much more timeless than the dust-covered artifact that spawned it as a result. The tone has changed drastically for the darker, which almost sounds ridiculous considering that this is a game about monkeys rescuing a gorilla from a crocodile dressed like a pirate. But somehow, DKC2 pulls it off.

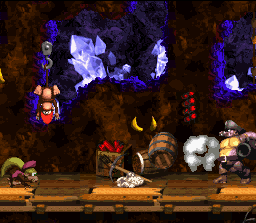

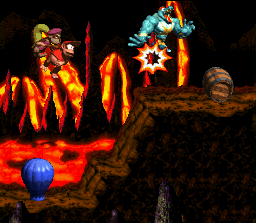

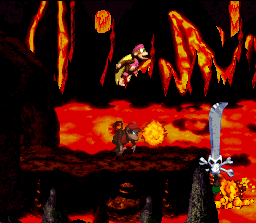

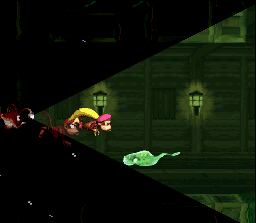

It doesn’t end there. The game’s environments get increasingly varied as you leave the ship, but everywhere you go you get a much stronger sense of identity with DKC2 than with the first game. From the sparkling, gem-filled chasms in Crocodile Cauldron, to the murky, moody swamps of Barrel Bayou, and the surreal, haunting woods of Gloomy Gulch, the locales of DKC2 are as much the heroes of this tale as the plucky simians out to traverse them.

And traversing them is a lot more fun and rewarding. Yes, we’re still running to the right and collecting stuff, but doing so is a much more tense and enjoyable affair thanks to a much greater focus on level design, a field in which DKC2represents almost unparalleled skill for its day. It’s hard, even now, to get through levels like Bramble Blast or Chain Link Chamber and not be taken aback at how ingenious the design is nearly every step of the way, that not a single moment in these stages was taken for granted and not realized to its fullest potential for the amount of fun you could have with them.

DKC2 is also more rewarding in a more tangible sense. The bonus levels from DKC return, though DKC2 utilizes them in a much more structured way. Every stage has 1-3 bonus levels which are accessed either by breaking walls, picking up cannonballs and carrying them to their corresponding cannons, or, more often than not, finding and making your way into a marked bonus barrel. But where the rewards in the bonus levels in DKC were pretty insubstantial, typically coming in the form of more bananas and extra lives, the goal in every bonus level of DKC2 is to get a Kremikoin, a massive golden disc that, while seemingly innocuous, marks the beginning of a trend that will paint Rare’s entire future with Nintendo.

You see, you can run through DKC2 and beat the game just fine, and you’ll have a wholly worthwhile and unforgettable gaming experience for it. But something bigger beckons to you from beneath all the callow platforming. A game within a game. Enter the “Collectathon”.

Every world starting from the second in DKC2 has an area called “Klubba’s Kiosk”. Klubba is a massive, hulking Kremling somewhat disgruntled with the ordeal of taking orders from K. Rool. Being somewhat business savvy, Klubba sets up Kiosks at various sites around Crocodile Isle that lead to a lost world, and to gain access to this lost world through one of these kiosks, you need to pay Klubba 15 Kremikoins. Each Kiosk leads to a different level in the lost world, the stages of which are much harder than your standard fare, and it works out that you need to find every single bonus level in the game to afford to visit each stage in the lost world. And only after conquering each of those levels will you be able to fight the real end boss and see the real ending.

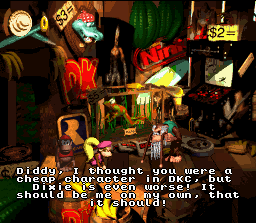

Also in every stage is a DK Coin. These are not hidden in bonus levels, but are equally as elusive and difficult to collect. But alas, there is a missed opportunity here in that collecting DK Coins doesn’t actually give you anything tangible the way the Kremikoins do. Rather, all it nets you is a place on Cranky’s post-game ranking chart (where you compete with Mario, Yoshi, and Link for a spot as the most meticulous collector) and yet more percentage towards the game’s coveted 102% completion rate, a trophy that would inspire one to bring their DKC2 cart to all their friends’ houses and show them that they indeed accomplished such a task, many years before the advent of “Achievements” and “Trophies”.

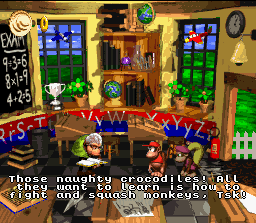

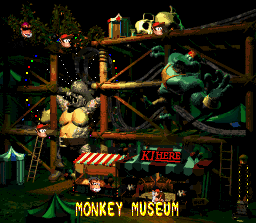

Also collectable are Banana Coins. These are used to barter with the various Kongs that you can visit on the area maps. There’s Cranky, who gives you hints about how to find things in stages or how to defeat bosses, Wrinkly, who saves your game and also gives you advice on various abilities you have at your disposal, Funky, who allows you to travel between the different areas of the island, and Swanky, who hosts a trivia game show where you can win lots of extra lives.

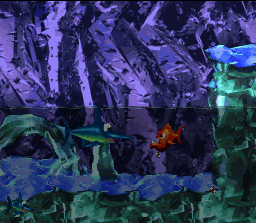

Animal buddies make a return from DKC as well, but this time, they’re a bit more integral to the gaming experience. Not only do you get to ride them, but sometimes you even transform into them and play as them to traverse specific parts of a level. Rambi, Enguarde, and Squawks return from the first game, but Squawks now has a much bigger role in that he carries you as he flies through stages. Joining them are newcomers Rattly, a snake who can jump very high, and Squitter, a spider that can create web platforms wherever you desire.

It doesn’t hurt that DKC2 looks and sounds much prettier than DKC (quite a feat for the latter). Rare definitely got a lot of bugs out of their Silicon Graphics modeling workstations in the year that transpired, and the result is a game that looks less like a liquid plastic animal orgy and more like a claymation sequence from Beetlejuice or one of Pee-Wee Herman’s nightmares. What really sells it is the level of detail and sense of character each stage type exudes. In areas like the forests or the swamps, it’s easy to get lost in the backgrounds and imagine that somewhere in the distance, other adventures are being had.

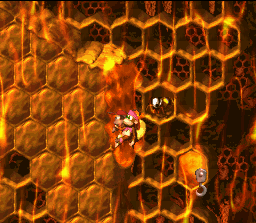

What really sells DKC2 is the music. Dave Wise returns to compose his magnum opus: a sweeping, enchanting, and highly infectious masterpiece of brooding symphonic and electronic melodies. This is one of the greatest soundtracks of the 16-bit age, and Wise’s work here deserves to be held alongside the likes of Koji Kondo, Yuzo Koshiro, Nobuo Uematsu, and all of the other great composers of this or any era. The pounding percussion and tolling horns of the overworld map theme; the frenzied electronic notes of the hornet hive stages; the cascading piano riffs of the lava pits; the moody, suspended notes of the forest stages; and most of all, the weaving, bobbing crescendo of electronic notes that comprise the Stickerbush Symphony.

There really isn’t anything to complain about when it comes to DKC2. If you hated Donkey Kong Country, Diddy’s Kong Quest isn’t likely to win you over. But if you thought DKC was even mildly entertaining, you’ll love DKC2. It represents a high-watermark of game design in a time when the gaming landscape was changing rapidly and games were being redefined. In less than a year, a 3D revolution and a sharp pendulum swing toward darker and more mature content would mark the end of gaming’s Golden Era, and DKC2 is one of that era’s triumphant, fist-shaking last hurrahs.

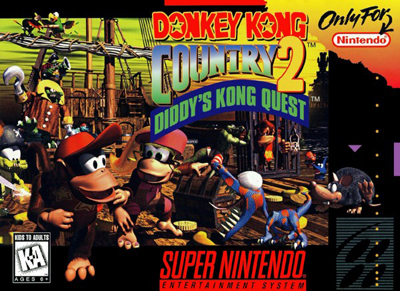

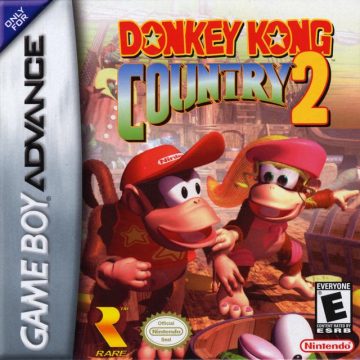

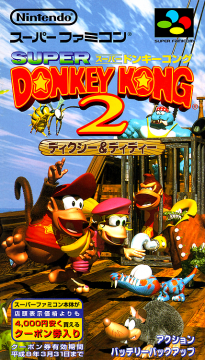

Like the first game, DKC2 was tweaked and rereleased for the Game Boy Advance. This version fares a little better than the port of DKC. More time was clearly taken in converting the graphics and the game doesn’t look too bad even with the brightening and lessened resolution. Also like the first game, there are few new mini-games: Diddy’s Dash is a time trial mode, Klubba’s Bag-a-Bug is a bug collecting mini-game, and Expresso Racing is what its name implies. Yes, Expresso returns in the GBA version of DKC2, not only for a mini-game but also for a couple of all new stages. There’s also a lot more stuff to collect. There is now a Golden Feather item in every stage, which build up Expresso for the racing stages in various ways. There are also photographs you get by defeating certain enemies. These photographs are used in Wrinkley’s Scrap Book, which is a roundabout way to get more DK Coins. The SNES version is still undoubtedly definitive here, but the gap between the GBA port and the original is much smaller than the portable versions of DKC.

The “Cranky’s Video Game Heroes” screen features a number of Nintendo cameos, including Mario, Yoshi, and Link. Most amusing are the items by the garbage can, labeled “No Hopers”, which are jabs against other popular 16-bit characters – the red shoes are a reference Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog and the red gun belongs to Earthworm Jim.

Screenshot Comparisons