You might not expect much from Donna: Avenger of Blood at first glance. A freeware Adventure Game Studios production with stilted, sloppy graphics that is colloquially referred to as that “one game with the naked chick”, it might not strike you as the most appealing option in the glut of the indie games market. But give it a chance and you’ll see Donna is an impressive, well-conceived piece of work, making up for its rough edges with one of the most intelligent, socially relevant adventure game narratives in recent memory.

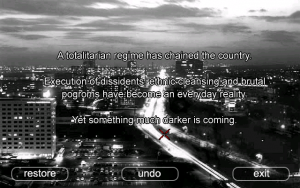

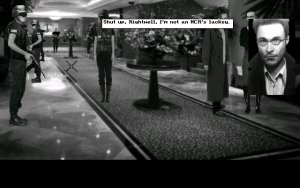

In a nameless Eastern European country, cultural unrest and financial destitution have allowed nationalism and extreme right-wing politicians into the forefront of its political landscape, a situation which of course has absolutely no parallel in the real world. A vampire (Yes there are vampires too, actually one of the less insane things going on in this game) named Christian takes his partner Donna to a mysterious city for a secret purpose. The game begins in a hotel, as the two lovers chat in the nude, when suddenly Christian is murdered by a fascist men’s organization dubbed the Countrysons. Donna manages to escape, but she is naked, weak, lost, and confused. She nevertheless gets away from the Countrysons for the time being and pursues a quest of vengeance for her lost partner. Along the way she meets allies, discovers the even more corrupt underbelly of this derelict city and discovers a force at work even more occult and malevolent than the Countrysons.

As a vampire, Donna is endowed with certain supernatural abilities: Throughout the game the she makes use of her super strength, super charm (basically brainwashing), telepathy, and superhuman hearing. Donna‘s puzzles and gameplay are, for the most part, centered around these abilities. She can’t use these abilities on a whim however, as they require an amount of her blood in order to work properly. Blood level operates sort of like MP: In order to increase her blood level, Donna has to travel to a local park, seek out unsuspecting victims and suck their blood, or else gain blood through a variety of other predesignated plot-points. While tedious in practice, from a narrative point of view these trips to the park are a great way of demonstrating Donna‘s moral ambiguity. The narrative puts us squarely in her corner, yet this touch reminds us of her ultimate inhumanity. She isn’t above killing random people in the park in order to feed off them.

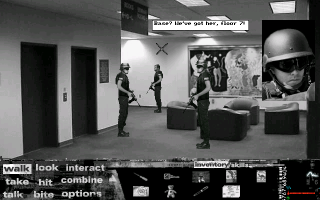

Once this system reveals itself, Donna isn’t too much of a challenge. Random death situations are rampant, but the trial-and-error feels intuitive for the most part. One puzzle for instance has you trapped in a hotel by the Countrysons, who know your room number. Since you can’t escape the building, you do the logical thing and switch the number plates on the door. The first time you do this you may only switch two plates, thus putting the hotel rooms out of numerical order. The Countrysons will notice this and come into the out of order room and kill you. Flip the entire line of hotel rooms instead, though, so the numbers are in reverse numerical order, and the Countrysons won’t suspect a thing. Dying in this situation sucks, but it makes sense why there’s an extra step, and the death in fact gives you a clue as to what you should have done differently the first time.

The biggest problem in the gameplay is starting out, because Donna doesn’t do a fabulous job of first explaining itself to the player. In the beginning, for instance, Donna is trapped in an alley with the exit blocked by a Countryson seeking to kill her. It’s supposed to be a tutorial puzzle, only the game doesn’t inform you about the blood level system. So you try to solve the puzzle in a traditional point-and-click adventure style, fail to find anything helpful in the area, and get shot time and again. Eventually you may locate the dead rat hidden in a dumpster, but you might not put together that you need to suck the vermin’s blood for strength. You can smoke cigarettes to get hints on how to proceed, but this too is an as yet obscured feature.

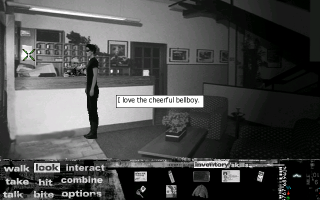

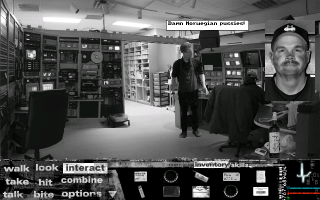

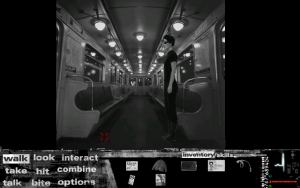

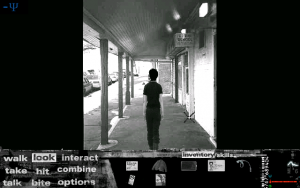

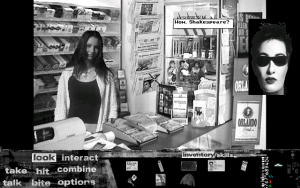

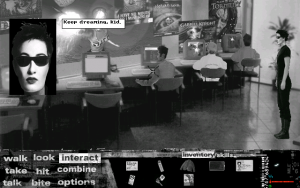

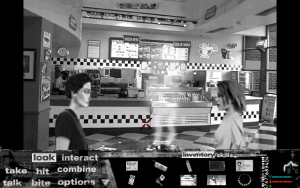

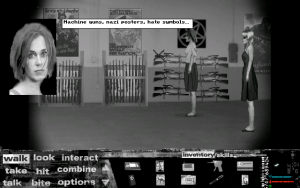

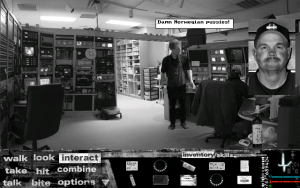

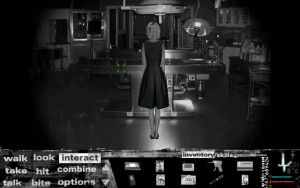

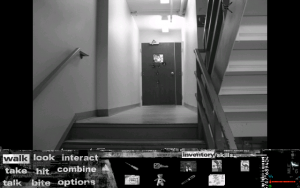

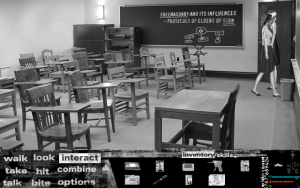

The LucasArts-style verbcoin interface and inventory are about as intuitive as the system can get. How much the player likes or dislikes it comes down to personal preference. The impressive part of Donna is the attention to detail in how the verbcoins respond to the world: Each option (“Talk”, “Look”, “Interact”, etc.) produces a different message for different hotspots. Not all are actually helpful or world-building, but it goes to show the devotion to detail that developer Błażej Dzikowski gave to the writing.

Sometimes, though, the writing is a bit much. It’s almost universally good, but it does slip into indulgence on occasion. One egregious sequence has you infiltrating a club of armchair philosophers. You have to prove your philosophical bona fides to the club, and requires reading extremely dry, long inquires into the nature of being and the like, then reading through and responding with equally dry, long responses to said inquiries. Even if the barrage of overly technical jargon is the point, it’s only funny for a minute. When the reading takes over all other elements of the game, it goes too far.

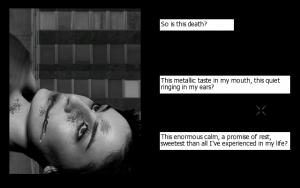

The other downside of the writing is its pacing. For a game about fascists, demons, vampires, ghosts, an ancient cult, and meta-dreams, it takes a while for all of this to start to come together and make sense. There’s an aimlessness to the first few chapters of the game, which suits Donna’s character arc but feels underwhelming to the player. Once it takes off, Donna‘s story is hard to beat. The existential horror and political despair will keep you thinking long after the game is over. But for an hour or two prior, it’s a drag to reach.

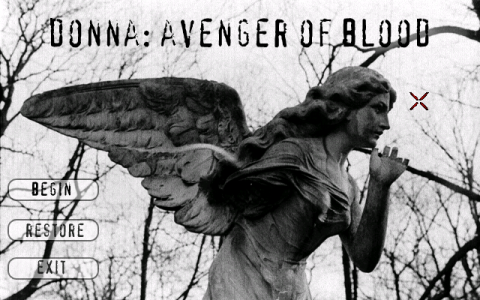

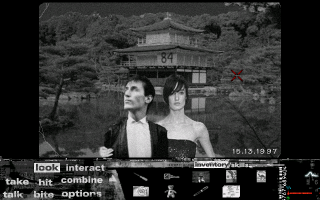

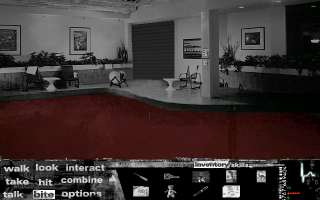

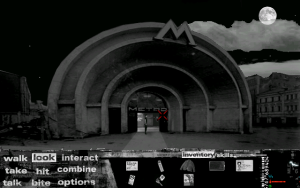

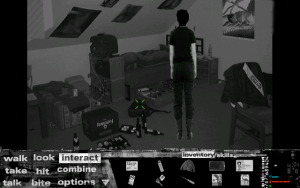

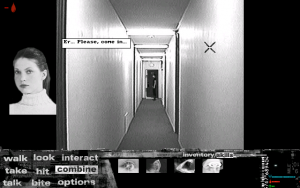

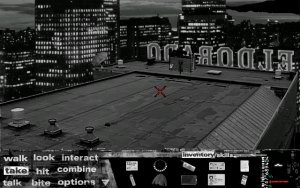

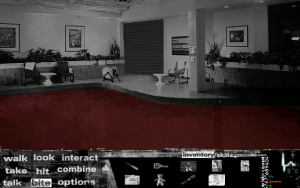

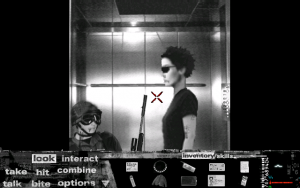

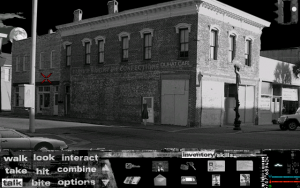

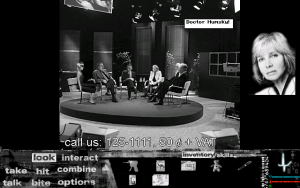

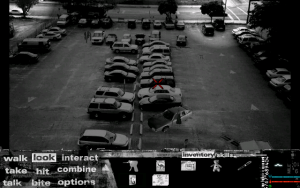

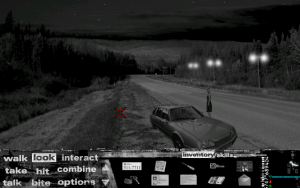

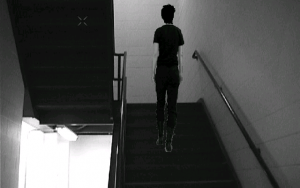

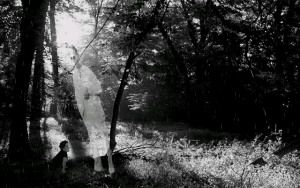

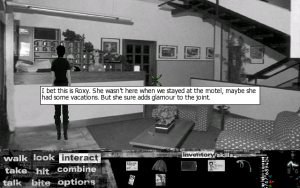

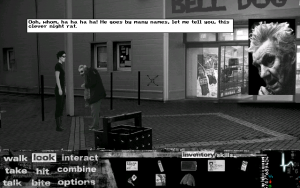

The distinct, ugly-but-alluring photographic graphics are Donna‘s most distinct stylistic touch. Perhaps growing out of the aesthetic of the FMV craze of the ’90s (Phantasmagoria and The Beast Within), Donna‘s graphics do two distinct things: Turn images of real-life people into animated sprites and take background photographs and edit them into a coherent game environment. With images taken by photographer Dominika Dzikowska, the resulting effect is a uniquely uncanny visual effect. Characters idle in eerily static poses, then animate jaggedly in action. Backgrounds are all uncomfortably still, carrying with them a feeling of dread and uncertainty.

Donna: Avenger of Blood uses black and white visuals to mingle that uncanny stillness with the look of a dirty, beaten-up VHS tape. Sound helps immensely in this case, with odd, simple synthesized tunes in the background throughout the game. It’s reminiscent of those Shaye St. John performance art videos. Nothing seems right despite the setting looking ostensibly like a normal city. Something is just plain wrong under the surface. People move oddly, talk oddly, sound oddly. Their world is so incontrovertibly and wonderfully bizarre. It couldn’t be accomplished the same way with 3D visuals. Neither pixel art nor drawn visuals carry the same effect. It’s this stark contrast between the jagged, awkward cut-and-pasted photographic visuals with one’s expectation of what it should look like that drives its oddness so effectively. It looks bad through one perspective, but with the right ambiance, the right mood, it works perfectly, and such is the case here.

Donna has multiple endings, with the more complex, satisfying, and baffling ones involving several more steps to get to. Each leaves the player with a number of interesting moral questions, though some may be unsatisfied with the relative abruptness of these endings. The world builds itself almost too much to be dropped by the end. There are so many wonderful, memorable characters in this game, from the weird but charming Dr. Mulkin to the intrepid reporter Milena Tinto, that it’s difficult to let them go.

Given that Donna took roughly a decade for Błażej Dzikowski to complete, it’s fitting that we find trouble leaving the game behind. So much clearly went into it, displaying as it does a great deal of reverence for the dystopian horror genre and for point-and-click adventure games. It’s a messy, disturbed game with its fair share of quirks and flaws, but an impressive one for a one-man team (heck, it’d still be impressive with a full team). More than anything it manages to be memorable. Its unique aesthetic and nuanced narrative aren’t anything you’ll likely see in mainstream games. Or if they are, they won’t likely be executed in quite this inimitable of a way. Donna is worth your time for this alone: There are many games that play similarly, but none are anywhere near the same.

Links:

Official game website

AGS Page

Game walkthrough