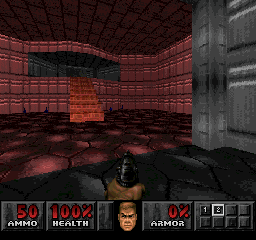

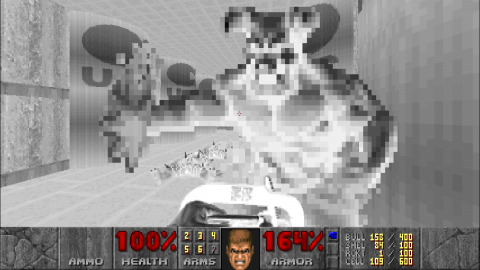

Note: Screenshots, unless stated otherwise, come from The Ultimate Doom re-release by Nerve Software for PC, which does tweak the graphical fidelity of the original game, but otherwise remains faithful to the original style.

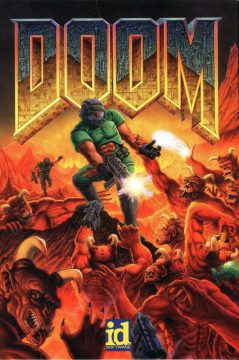

In 1992, id Software used John Carmack’s new rendering technology to release the action packed Wolfenstein 3D. The game was central to the development of the concept of first person shooters, showing a twitchy speed not seen in first person games to that point, and then one year later they defined the genre in its most basic foundations with Doom, a game that was installed on more PCs than Windows at the time. They made it in a building they called “Suite 666” because id Software was founded and run by turbo nerds. Beyond John Carmack, the team included John Romero, Sandy Petersen, American McGee, and Shawn C. Green as programmers and level designers, Adrian Carmack (no relation) and Kevin Cloud as artists, Michael Abrash and Dave Taylor as additional programmers, Tom Hall as the creative director, and Bobby Prince as the musician. They got the idea for fighting monsters with tech from a tabletop game they had (similar story for Quake) and Carmack took a quote from The Color of Money for a title. Doom is the alpha and the omega of the FPS, what made id Software the powerhouse it is today, and inspired countless developers across the world with its mod friendly design. It was all thanks to these brilliant developers.

Pictured: Some of the most important people to ever exist in the gaming medium.

Yes. These guys.

Doom is a story-light shooter because the team kind of threw out Tom Hall’s horror story to focus on intense shoot-bang-run action. You are a space marine, the “Doomguy,” and you are trying to stop a demonic invasion on the Mars moon Phobos caused by idiot scientists trying to make teleportation a thing, eventually leading you into hell. You start with a pistol and your manly fists (that you can power up with a berserk pack for an entire map’s length), and can nab a shotgun, chaingun, plasma gun, rocket launcher, chainsaw, and the infamous BFG or “big fucking gun.” That last super powerful weapon fires a big green energy orb that kills everything in the general area, and even affects enemies through walls. The pistol and chaingun share bullets, and the plasma gun and BFG share energy cells. The formula is similar to Wolfenstein 3D: Kill demons, get through the maze heavy levels, find colored keys, repeat as needed. The simplicity is its strength.

There are a handful of enemy types, including undead human grunts (zombieman and shotgun guy, yes really) that wield their own pistols and shotguns, as well as imps, which shoot fireballs which can be dodged, if you’re nimble enough. Pink demons or pinkies (just known as demon officially for awhile) don’t have projectile weapons but run straight at you with tremendous speed and take a few hits before going down, plus there’s an invisible-type called spectres which are harder to see. Cacodemons are one-eyed floating heads, whose designs were lifted from a Dungeons and Dragons book, plus there are flaming skulls (lost souls) flying about, eating up all your ammo. There are also three large creatures that are initially used as bosses but are occasionally placed as regular enemies in later games and levels, including the large Baron of Hell, the enormous cyberdemon, and the even bigger spiderdemon, also called the Spider Mastermind.

Doom was an incredible technical leap over Wolfenstein 3D. The levels of Wolfenstein 3D were laid out with blocks on a large grid, since the walls were only positioned at 90 degree angles. Doom has much more complex design, with angular walls of arbitrary lengths, allowing for more free-form room creation. Floors and ceilings are textured, and there are skyboxes for the occasional outdoor environment. Sector-based lighting allows for rooms (or parts of rooms) to have lighting values, and can even blink, adding to the spookiness. Floors can move up and down too, effectively creating elevators. The number of textures has also greatly expanded, though the game has a general “brown/red/silver” color palette, depending on whether you’re in the starbase levels or the hell levels. Also added is a head bob for the onscreen weapon, mimicking actual walking/running motion compared to the completely static guns in Wolfenstein. The game tops out at 35 FPS, which back when it came out required at least a low end Pentium to hit. Options to change the screen size or run in a low resolution, low detail mode allowed players with then-crusty 386 CPUs to play the game, albeit somewhat compromised.

However, the engine isn’t entirely 3D – it’s unofficially termed “2.5D”, not to be confused with the concept where side-scrolling games use 3D graphics. Floors can be positioned at different heights, allowing the game to feature stairs and even windows, but rooms cannot be placed over other rooms, nor can characters exist on top of one another. Normally, the game simply won’t let you exist in the same space as another enemy, though if you teleport into one via a teleport, it’ll kill the other character, termed “tele-fragging”. With this, you can’t look up or down (a feature added to the engine in the later Heretic, though it’s not used for much). You never need to worry about hitting foes at higher or lower altitudes, because the game automatically adjusts the height when you fire. You can’t jump either, though in a few cases where you need to leap between platforms, you simply run and let the inertia carry you over.

Technically Ultima Underworld beat Doom to the punch in having such an elaborate graphics engine, and that one is actually more technically accomplished, allowing for things like slopes. But Ultima Underworld is also a relatively slow-paced RPG, while Doom is a fast-paced action game.

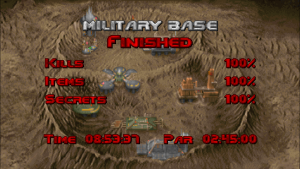

The game hits all the right notes, requiring you to think on the fly with your weapon selection against the variety of monsters you have to face. Sure, blasting imps with rockets is fun, but better to have those ready for a room full of pinkies or the odd baron of hell. There are keycards to find, puzzles to solve that are mostly coherent and involve flipping switches (though later episodes start to test things), and a crunchy soundtrack by Bobby Prince that pays tribute to all your metal faves in glorious bit crush noise. It helps that the first episode, Knee Deep in the Dead, had the best maps of the game by far (Romero having the stand outs). That made up the shareware version, and that’s what made Doom a phenomenon. The levels are short and sweet, while giving plenty of action, avoiding some of the bloat later episodes would have (see Slough of Despair, the map shaped like a hand with a broken event trigger and far too many lost souls on Ultra Violence, the hard difficulty).

Doom was made by a bunch of dudes just wanting to do what sounds cool, in an era where games were simple enough to program that you could make an entire fleshed out game with hours of content in a few months. It had a transgressive mood to it nobody had seen from the medium before, at least so widely, and kicked off what the western 90s PC gaming scene would be like, for better or worse. It also invented deathmatching, both online through modems and via local area networks, even if Quake became the big multiplayer franchise, so that’s also a pretty big deal. This all happened entirely because John Romero was a fighting game nerd, amusingly.

That transgressive nature of the game did come with problems, though, mainly by making it an easy target by the media. While using video games as escapism isn’t really a problem anymore due to the industry being so massive now and therefore having influence on laws and policy, it was a different story back in the mid-1990s. The use of religious imagery kicked up a story from the church, it was caught up in the bizarre speculation on VR that polluted the 90s, the 32X version was one of the first games to get an M rating from the newly-formed ESRB, and there was a swastika in one of the maps as a Wolfenstein reference they removed after a vet complained. There was also the Columbine shooting in 1999, Doom being a favorite game of the perpetrators, where the media pin-pointed it as the cause of their acts, not unlike the satanic panic around D&D in the 80s. Retrospective views on the tragedy rightfully ignore that angle and instead focus on other, more concrete factors, like the pair’s interest in nazism and one of the duo’s severe emotional issues. Other scapegoats include The Matrix (because they wore trench coats) and Marilyn Manson for reasons that don’t seem at all coherent nowadays.

The full commercial version of Doom originally came with three episodes: Knee Dead in the Deep, The Shores of Hell, and Inferno. The retail version, called The Ultimate Doom, includes a new fourth episode called Thy Flesh Consumed, which was meant for expert players, and frustrates quite often. American McGee designed the first map and it instantly makes you miserable by forcing you to pistol a mess of monsters that teleport in and further make your life hell with a baron teleporting into the scene when you’re cornered. John Romero made the second map, which he made in a few hours, which is filled with death traps, including a surprise cyberdemon in the corner near the level’s end alongside a monster closet meant to distract you from the cyberdemon, and the infamous plasma gun trap that sends a mess of barons at you in a tight space. The episode gets better but those first two maps are just…maddening.

The fifth episode released by John Romero in 2019, Sigil, fairs much better, still with some hellish traps (it is a set of Romero maps after all), but some impressive moments and interesting stylistic decisions that even help with navigating levels without having to draw literal arrows in. It even comes with two full soundtracks, a MIDI one by James Paddock and an instrumental metal one by Buckethead. It’s technically not an official release, but come on, it’s John Romero, it’s as close to official as it gets.

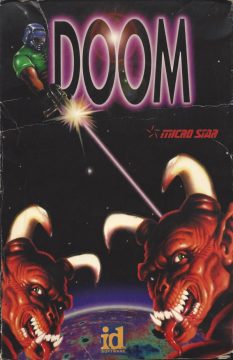

The various OS ports different in quality based on who was around to do the porting and the specs they were working with, but the console ports are just a wild ride of bad ideas, rushed execution, and just straight up rotten luck.

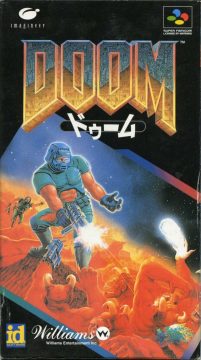

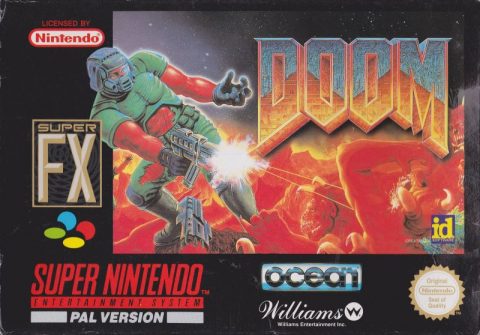

The SNES version relies on the Super FX2 chip as a co-processor. It doesn’t use the Doom engine but rather a new one called RAGE created by programmer Randal Linden. The visuals are presented in a window with a low resolution that looks like the DOS version’s low res mode. There are also several compromises made to reduce the ROM size, like the lack of floor and ceilings textures and enemy sprites that only face the player, plus there are only 22 levels. There’s no save or password function, so each episode must be played all the way through. However, the music conversion is excellent, as the sharp guitar samples give the music a much richer sound than the FM MIDI soundtrack found on typical PC Soundblaster cards at the time.

The 32X version by id Software themselves is mostly an improvement, but not much. It only features 17 levels out of the first two episodes, and is missing any kind of save feature. The visuals are better than the SNES but it still runs in a window, albeit a larger one. It also features sprites that only face a single direction and some removed enemies. It also has weird quirks, like the BFG having to be put in through cheats due to the missing third episode, or locking up on a DOS prompt if you finish the game with cheats or start on any level but the first. Probably the most egregious change is the music, which seems to have converted very hastily from the original MIDI files, resulting in a soundtrack that sounds absolutely terrible.

Jaguar Version

GBA Version

SNES Version

id Software also did the Jaguar port, which would have been the best of the bunch if not for the complete lack of music. There are some tweaks to the levels to reduce memory and processing load, and the altered versions created here were used for several later ports, including the PS1 version. 22 of the 27 maps are included, with two new ones added in. Some enemies are missing, like the cyberdemons and spiderdemons.

The 3DO port was a disaster that was in development hell for two years, basically programmed together by one person over an incredibly short period of time (Rebecca Heineman, a legend in her own right) with a new soundtrack brought together by the studio CEO’s garage band. The action is packed into a very tiny window, which can be tweaked with a code but causes the framerate to suffer massively, but their covers were pretty sick. Just listen to their take on At Doom’s Gate.

The PS1 version is probably the stand out, a mash-up of levels from both Doom and Doom II (though several levels have been cut) and a few originals. This version adds in some colored lighting which makes it look pretty different in spots from other versions, mostly giving the rooms with radioactive clime a green glow, as well as animated skyboxes. Aubrey Hodges also did a new soundtrack, moody new takes on the material like his work on the Quake ports and Doom 64, and many sound effects have been changed as well. There were technical limitations that resulted in some further map tweaks but the team clearly tried their hardest to make it work on the limited hardware, and it’s still far better than previously console ports, running at full screen with a relatively smooth frame rate. Due to the graphics and sound changes, this version has a very distinct mood that still makes it worth checking out. The Saturn version was going to port this version, but were forced by id Software to use software rendering instead of their original technique due to causing texture warping, resulting in awful frame rates.

3DO Version

32X Version

The GBA version is shockingly solid, considering the hardware. It’s based on the Jaguar set of levels and missing the same content, but runs fairly well, even if the visuals are little bright to compensate for the original console’s lack of a backlight. The music conversion isn’t great, plus most of the songs are used in incorrect levels.

All later ports were much smoother (minus maybe the glitchy version in Doom Eternal, which is there entirely to run Doom in Doom), working on better hardware, and thanks mainly to the hard work of Nerve Software (and Carmack for the original iOS version, now removed). The Xbox 360 version adds in split screen multiplayer and supports widescreen. This feature also appeared on the Doom 3 BFG pack, also ported to the PlayStation 3. From this point on, the medpacks were altered so that they no longer display the Red Cross symbol.

The most recent official port of Doom was also released on the Switch, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One. In addition to updating the engine to work at 60 FPS, it includes support for external WADs, at least ones that have been vetted by Bethesda. A Bethesda online account was required to download and play these when the first update went out due to a bug, but now it’s just an option for various bonuses.

Their modern digital release of The Ultimate Doom is probably the easier way to play, but you have fanmade options as well.

Chocolate Doom and GZDoom are the two most popular source ports for an authentic experience along with modern convenience, and your options from there just get nutty. Doom‘s mod scene is absurdly vast, complete with entirely new games made with its framework. And as for other devices, it would be faster to list the things Doom hasn’t been run on, which I’m fairly certain would be an empty list. Scientific calculators? Check. A thermostat? Yup! Pregnancy tests? You betcha. You could probably get Doom running on your microwave at this point, or even a toaster if it has a screen on it.

Probably the most significant part of Doom‘s legacy beyond its sheer influence is how it changed what id Software was, and what they would become. This is where John Romero became a rockstar, where John Carmack suddenly had the money to chase after his various interests and turning the loose studio into a proper business, where Tom Hall’s absence started a domino effect that would start being seen in full as the first Quake was developed. Games took longer to make, the staff got more ambitious, and the technology became more central. Doom could be considered the west’s first real blockbuster since the initial industry boom started by Atari, and the ripple of that achievement is still being felt to this day.

And, of course, a sequel had to follow, because they had a hit and they had to follow that success. What we got was indeed more Doom, and arguably even more than that.

John Romero is selling this as a poster

Links:

Digital Foundry Retro: Doom – A comprehensive look at all of the ports of the original Doom.