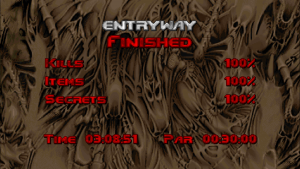

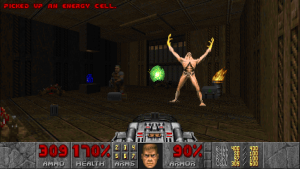

Note: Screenshots, unless stated otherwise, come from the re-release by Nerve Software for PC, which does tweak the graphical fidelity of the original game, but otherwise remains faithful to the original style.

Doom II, also know as Doom II: Hell on Earth, is the first retail release of Doom. id Software had a now-curious distribution model where the first game was not distributed at retail, and needed to be mailed away for, while the sequel ended up in stores. (Wolfenstein 3D followed a similar model with Spear of Destiny, though the first entries eventually made their ways to stores too.) While it is mostly a standalone expansion more than anything else, Doom II established the violent, gory chaos that would define the franchise in the wider public consciousness and among some of its future developers. The maze-focused design of the previous game was downplayed a bit for a greater focus on huge, ridiculous mountains of monsters trying to murder you and requiring even more face shooting then ever.

It is an amazing game that really defined what Doom was, but also pushed forward the idea that an FPS could be more than just exploring mazes with occasional gun combat. Rather, an FPS can be heavily focused on the shooting itself, with the level design facilitating special encounters. Doom defined the foundation, Doom II pushed forward its edgy, violent style as the norm.

John Romero’s role at iD is also very well documented now, with him being too busy producing games with Raven and deathmatching too much to actually do that much work, only having a small handful of maps on this one. iD was changing, and in that chaos, Sandy Petersen had to basically design half of the levels, with American McGee helping to pick up some of the slack along the way, while Romero remained a fairly small presence with just six maps. McGee handled most of the first third of the game, with Petersen making up the majority of the rest. Romero’s levels were sprinkled throughout Petersen’s, and also of note is the single map by Shawn Green, Bloodfalls, a solid addition with a cool blood motif.What does and doesn’t work here is mostly because of Sandy Petersen, and we can read his levels as a baseline for the overall quality.

This is Sandy Petersen today. All of these people are still nerds, god bless.

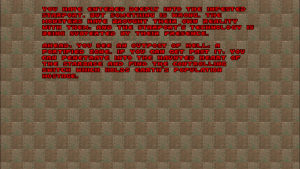

In the original Doom, the hellish demon menace was contained to just military installations in space, but now the creatures have reach Earth, so it’s up to the Doomguy to travel home to exterminate them. The game only has one new weapon, but that weapon is the Super Shotgun, and people aren’t exaggerating when they call it one of the best shotguns in gaming. It devours low-tier enemies and can do solid damage to larger enemies, saving rockets and cell ammo for hairier situations. To counter this, the gun takes two shells instead of one, and the new enemies are very dangerous and spice up encounters significantly.

The “heavy weapon dude,” more well known as the chaingunner, is a new possessed soldier type that can do a lot of damage quick in large numbers with his hitscan chaingun. The Hell Knight is a lower health Hell Baron that can be more easily placed in encounters without soaking up ammo, but remains a big threat. The Mancubus can take a lot of damage while firing fireballs with a strange arc to them compared to other projectile shooting enemies. Arachnotrons are the small brained children of the spiderdemon, now armed with fast plasma shots for high damage, though they can be dodged.

The pain elemental spits out lost souls and is the worst thing about this game, mainly there for eating ammo. The mighty arch-vile is both deadly with its odd explosion attack that cuts off your sight, and has a unique power to resurrect any enemy that leaves behind a corpse. Most importantly, there is the revenant, the boney, homing missile shooting, closet cramping skeleton, both a danger and a goofy presence with his awkward melee animation and general appearance.

With the first game under the belt, the team better understood how to use the elements of the game to their advantage, including making all these new monsters force the player to think on their feet. The trap game here is fantastic, especially in Tricks and Traps (obviously), finding a good balance between frustrating and challenging. Petersen gets some highlights himself, especially the chaotic Mancubus storm in The Suburbs, and there’s some charm to the jerkishness to Barrels o’ Fun since the level is at least nice enough to make what’s coming clear each time.

But, Petersen also made The Chasm, which is an infamously bad level for a reason. The cramped hallways would be fine if not for the eventual arrival of the titular chasm, an obnoxious thin line maze over acid that loves to spawn monsters at the most inopportune moments (which is basically any time you are traveling through the chasm, which is all the time during this section of The Chasm). A level that has a segment where you enter a new chasm where you teleport in right next to about ten lost souls that push you into a pit with no way out is a bad level.

Most unusual is the final boss, named the Icon of Sin which is a gigantic head painted on a wall, with an opening on its head. The only way to destroy it is by aiming and firing a rocket at just the right position, sort of like trying to hit the weak point of the Death Star. If you miss, you use a teleporter to go back up to the top and try again. If you use a cheat code to clip through the walls and see inside this weakpoint, you’ll find a digitized image of John Romero’s skewered head.

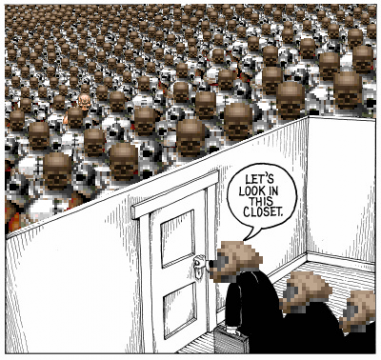

Doom II is a constantly shifting mix of highs and lows, and while the worst lows are fairly low, they can be forgiven as early genre experiments (except The Chasm, which will not be forgiven). The highs, however, are ridiculously high, from Petersen’s completion of an old Tom Hall map with the heavily populated and secret heavy Refueling Base, to Romero’s Gotcha! and its surprise spiderdemon and cyberdemon fight. Romero also got the second to last level with The Living End, and it is fittingly hectic, while Petersen’s The Spirit World had a revenant monster closet that will be meme’ed through the Doom fanbase for ages.

Buddy, just wait till we get to Plutonia.

Do be warned it can be a big rough at times. The Pit, an early game level, will devour your ammo due to all the pain elementals on Ultra Violence. Secrets are a bit stranger this time around, the team more aware of the odd falling physics of the game and using that for platforming secrets. There are a lot more mean traps to look out for designed to wear down your ammo pool, so you can’t get complacent. It’s a lot of fun, but those odd moments of frustration pile up. The game is basically three episodes strung together so take your time if you need to, especially if you’re a secret hunter.

The music is more of the same for the most part, Bobby Prince back doing his usual “metal metal to MIDI” thing, while the slightly updated engine mainly focuses on letting the team make more unique structures in the game. The team all tried their hand at making spaces that looked like places that exist somewhere, which is ultimately a failure since this is still the Doom engine, but still admirable in what they managed to accomplish with their limited resources at the time. There’s also more trickery with event triggers to make levels flow differently and have a greater spectacle to them, like making a building collapse or shooting down a long hall full of flying cacodemons. Special mention must be made to American McGee’s Underhalls, the game’s second level, which introduces the ridiculous number of enemies you’ll be fighting regularly from now on. It’s very well paced and eases you in well, leaving you wanting more.

There’s also a lot to be said for the last third of the game, where the maps get more imaginative. The Hell levels this time look way more interesting then in the first game, Sandy’s The Spirit World doing a great job of using flesh textures, lava, and distorted colors. Some of the most striking levels in terms of style in classic era Doom are found here, alongside the attempts at depicting actual places. Great use of decorative corpses and blood, well done stuff.

If you want more besides the extensive mod community, check out the Master Levels, officially released fan maps made by some of the best true doom murderheads out there. There’s also No Rest for the Living, a unique episode initially made by Nerve Software for the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 ports. It’s pretty well liked and can be easily downloaded via the add-ons section of modern ports, which also include a listing of other mods from the scene. Other than that, you could try searching out the Doom 3 Collector’s Edition Xbox releases, which included Doom II and a unique secret level with Nazis in it (they only pop up in the base game via the two original secret levels, which remix Wolfenstein 3D maps). You can also find the level, titled Betray, from the fansite Classic Doom.

If there’s one thing special about Doom II besides what it did for the franchise, is that it’s the last Doom game of classic Id, before everything would unravel with Quake. It has that vibe to it that only the old guard could bring with their unique mix of passions.

Doom II didn’t receive any standalone console ports at the time of its release, though its levels were typically combined in with other ports to make one big mega-game (even if some levels were excluded.) This includes the Saturn and PlayStation and the Final Doom port on the PS1, which uses some of the Master Levels stages. Doom II was released separately on the Game Boy Advance, but unlike the port of the first game, which converted the Doom engine, uses a completely different 3D renderer. But again, it’s solid considering it’s so tiny. However, once again, modern ports are the best way to play for newcomers.

The next two games in the classic Doom era are a bit different. Instead of Id doing them in-house, since they were busy with a new franchise and slow self-implosion, they looked to the community. Romero took notice of a team called TeamTNT, and in that process, took notice of two brothers named Milo and Dario. Dario Casali would later to go on to help design Half-Life. Before that, there was Final Doom…and Plutonia. And TNT Evilution too but mainly Plutonia.