Nothing exists in a vacuum, and the cyberpunk-themed PC Engine shoot-em’-ups of the Download series are indeed children of its time. The games were released just a few years after the 1988 Akira movie and the impact of that film along with William Gibson’s Neuromancer novel from 1984 have left clear traces on these games. Unlike the ships and aircrafts of most other shooters, this series has you piloting a red motorcycle that also acts as a network terminal to jack in your brain to the cyberspace — two of the most iconic parts of the aforementioned works. The games also set themselves apart from its peers by its dense story and high amount of cutscenes, which was unusual for the genre at the time.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Download series is that it was an unsuccessful attempt at establishing a new multimedia franchise – or as the Japanese call it: a media mix (メディアミックス) – based around a new shoot-em’-up video game. Within two years, publisher NEC Avenue and partners produced two PC Engine games, one light novel and one direct-to-video anime. However, as time would tell, the series was not strong enough to develop into a larger franchise, and was never continued after the anime. None of the entries were released outside of Japan, which is too bad, since there are quite a few aspects here that are unique and well-executed enough to create a compelling cyberpunk series. One reason why the series never caught on might be the stylistic incoherencies between the different entries (e.g. characters’ looks and traits change considerably over the course of the series), but it is also this motley implementation that makes the series interesting and charming today. The games seem to have gotten average reviews at the time, which would have made it even harder to establish the franchise. Another reason for its continued obscurity today is probably the in-retrospect unfortunate choice of name. Although Download might have been a cool name back in 1990, time has not been gentle on this title: it is very inconvenient to try to search the internet for “Download PC Engine”, or, even worse, “Download anime”. The same goes for searching for information on Japanese webpages, since the Japanese spelling of the series title (ダウンロード) is also the Japanese word used to prompt a file download.

The series is set in a 22nd century world where the human brain has become immortal after technology has advanced so far that the mind can be digitized and stored in a large cyber network called “Down Load”. The state has bankrupted and society is governed by huge enterprises who control the cyberspace. The hackers in this universe are called cyberdivers and they jack in to the network via their cranial nerve. In true Japanese fashion, the act of cyberdiving is abbreviated to cyving, which doesn’t have the same ring to it in English. By diving into the network the hackers basically also dive into other peoples digitized minds, which opens up for some really interesting philosophical sci-fi narratives. However, as we will see, the creators of the series didn’t manage to fully realize the potential of this premise and it is, most of the time, sadly underused.

The Download games were published by NEC Avenue, the media development division of NEC that was originally formed as a record company in 1987. NEC Avenue published a number of PC Engine ports of Sega arcade games (e.g. Space Harrier, OutRun and After Burner II), but Download and its sequel are two of their more interesting original titles. As for who the developer(s) of the Download games were, well that is a more difficult story. From the packaging and in-game credits, one would assume that NEC Avenue also developed the game, but there are quite a few mentions online that the programming was handled by Alfa System (including the company’s old webpage). Alfa System developed a number of games for the PC Engine in 1988-1995 (notably the ports of Ys Book 1&2, Wonder Boy III: Monster Lair and Dynastic Hero, and the first ever PC Engine CD game No-Ri-Ko) before they went on to develop for other consoles, for instance the portable spinoffs in the Tales series. A second company called Sofix is actually credited in the games. In the credits roll of Download they are featured under the “Thanks” heading, and in the sequel Download 2 as well as the anime adaptation they are credited alongside NEC Avenue. Sofix is a more or less forgotten Japanese developer that made a few games for the PC Engine in collaboration with NEC Avenue and Hudson. In 1992 – about two years after the first Download game – they published a digital comic adaptation of the Yawara! manga on the PC Engine, which had a look and quality very similar to the cutscenes in the two Download games. By educated guesswork, it is likely that Alfa Systems were in charge of the gameplay of Download and its sequel while Sofix handled the cutscenes, but there is very little evidence available to back this up.

The first game and the light novel were produced in parallel and released less than a month apart. The book was written by Wataru Nakajima who also worked on the story for the two games. He had previously worked on the 1989 Famicom-exclusive Seirei Gari (a Deja Vu/Shadowgate style adventure game) where he was credited for the original story. Interestingly, the credits of Seirei Gari also list Sofix and their employees, meaning that Download was not the first time Nakajima collaborated with them. In the first game Nakajima is listed under “Novels” whereas Ken Ohmori was credited for the scenario, so it is not entirely clear how much Nakajima worked on the first game.

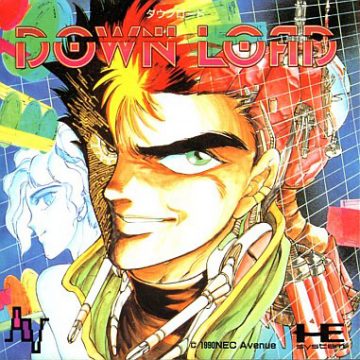

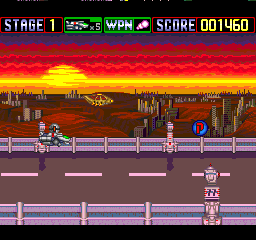

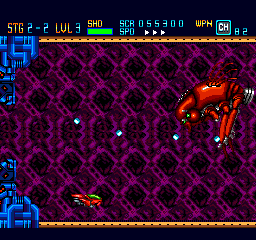

As will soon be evident, the series struggles to keep a coherent style despite the producer (Toshio Tabeta) and executive producer (Makoto Sakio) remaining the same for both games. Masaomi Kanzaki, the artist behind the Street Fighter II and Dragon Quest VI manga adaptations did the character design for the first game, and gave a rather edgy style to the main characters Syd and Deva that works well with the cyberpunk setting. He was for some reason replaced by another manga artist, Shuho Itabashi, for the character design of the second game that was released less than a year after the first one, and their difference in style clearly shows. The second game goes for a more down-to-earth character design, with the effect that everything looks weirdly mundane and more space opera than cyberpunk. For instance, Syd’s head-jack has been replaced by an incredibly dorky-looking helmet, and Deva has been stripped of all her cool and looks more like a concerned mother than a rogue hacker. Throughout the series, Syd uses his motorcycle to connect to Down Load (the bike is called Motoloader – or possibly Motoroader due to the nature of katakana – which is possibly a reference to the PC Engine Motoroader games by Masaiya), but in the second game it has been redesigned to a clunky spaceship instead of a hoverbike. The anime takes it back to the original red bike, thankfully.

The main composers also changed between the games. Yasuhiko Fukada wrote the music for the first game and would later make the soundtracks for a few Bomberman games. His PSG soundtrack for Download is delightfully gritty with pounding synth basslines and is well-fitting with the overall aesthetics of the game. The second game uses both PSG and CD music, and was made by three new people: Kimitaka Matsumae, Tadashi Kitamura and Suguru Yamaguchi and is much more guitar-driven than the first.

At first glance, it is easy to write off this series as yet another cyberpunk story, but it has, like any other work or media, to be considered within its contemporary time. The Download series could be argued to belong to a second wave of cyberpunk, that is in essence very much post-Akira, but the influence of the Megazone 23 anime (1985) and the Ghost in the Shell manga (1989-90) are also very tangible. Megazone 23 features a red motorcycle that is a terminal to a advanced computer network that controls the society, and Ghost in the Shell’s villain can hack into humans with cybernetic brain implants. Given that none of these three trendsetting works had any (good) video game adaptations at the time, Download does somehow manage to avoid being a direct rip-off despite wearing its influences on its sleeves. The series’ four entries will be presented in release order below.

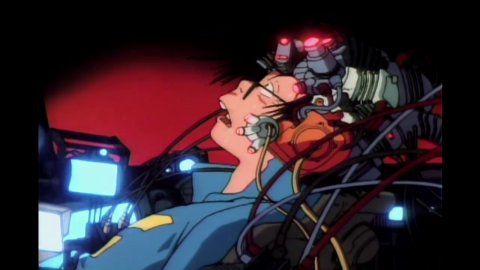

Although it clearly belongs to the vast majority of sci-fi themed shoot-em’-ups on the PC Engine, Download is a stylish game with a certain je ne sais quoi. It has a very involved plot for a shooter with lots of nice looking cutscenes, which was quite unusual for its time. This type of anime style pixel art cutscene would later be a staple of the PC Engine CD ROM, and it is particularly impressive how they fitted all this into a HuCard.

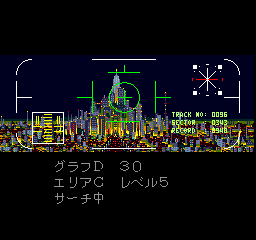

As the game begins, you are treated to a lengthy and good looking cutscene. It begins with a camera (supposedly a police drone) searching a high tech cityscape and zooming in on the main character – a cyberdiver named SYD2091 or Syd (シド) for short – sleeping on a sofa in his apartment. We see a flashback dream sequence of how one of his hacker partners got killed during a jack-in, and then wakes up to news that his other partner, DEVA3255, has been arrested by the police and that Syd is also a suspect. The news is interrupted by a pre-recorded video message from Deva telling Syd that their latest job was a set up and that someone is trying to frame them.

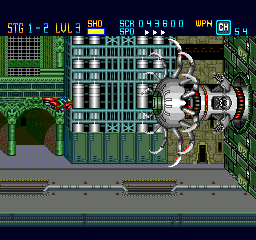

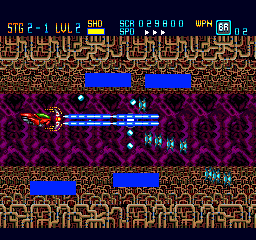

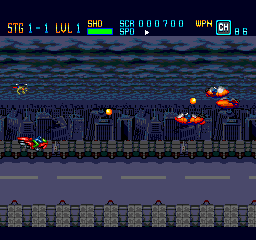

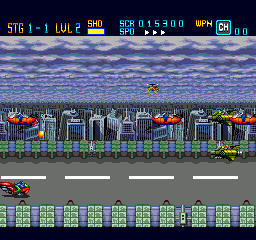

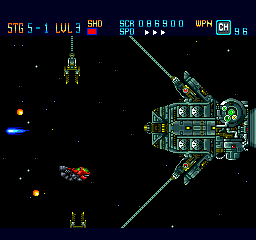

As the game begins, Syd is on his way to break Deva out of her arrest at the police station. The first stage is truly a showcase of all the things that this game does well. You are flying your hoverbike on a highway that invokes the opening of Akira while dawn slowly breaks over a high tech cityscape and the first boss is chasing you in the background. The action is fast paced, the parallax gives a nice sense of speed and you feel that you are powerful enough to break through the enemy waves in style. The whole level is a striking set piece realized in a bleak color palette with a few pastel highlights that fit the cyberpunk aesthetic well. In fact, the game sets the stakes so high in this first level that it later struggles to live up to this standard.

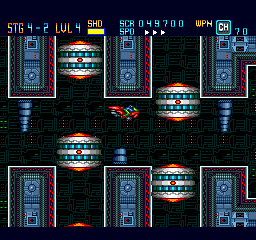

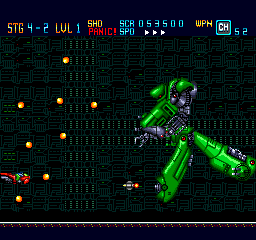

Unlike most other shooters of its time, the story continues with rather involved cutscenes in between each stage. After beating Stage 1, Syd breaks Deva out of jail and learns that he needs to jack in to the police network to delete a virus that has infested the police unit. In these jack-in levels, the bike morphs into a sleek looking spaceship and the action takes place in a abstract looking level to illustrate that Syd is now inside Download. After defeating the threat, Syd returns to the real world and is apprehended by two men-in-black who are just about to make The Big Plot Reveal when a robot kills them and kidnaps Deva. Syd then sets off to rescue her, and they later find clues that make them go to space to jack in to a space station to delete a virus called NERO that is threatening the Earth. There are a few twists and turns to the story, which at the end-of-the-day is a rather traditional sci-fi conspiracy narrative. Its biggest merit however is that it makes the world much more alive than it would have, had it not had the cutscenes.

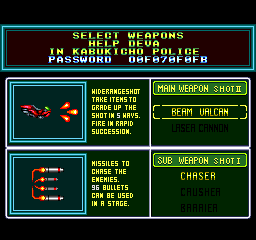

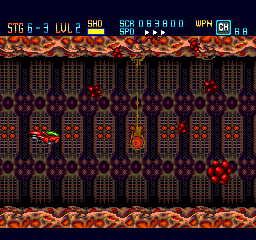

At the start of each stage you are presented with a weapons load-out selection, as well as a short summary of the current story and a password. You have one main gun that fires rapid-fire and has unlimited ammo, and one secondary weapon with limited ammo that you need to replenish with an ammo pick-up. There are two main weapons to choose from that can each be updated from level 1 to 5 (indicated in the HUD) by collecting a certain power-up: The Beam Valcan [sic.] shoots bullets at a fast pace and becomes a spread shot after one update; the Laser Cannon fires long lasers that penetrate enemies, but is a bit slower than the Beam Valcan, even after you update it. The higher the level of the main weapon, the more simultaneous directions it will fire. The secondary weapons are really useful and add a well-needed extra punch to your firepower. The Chaser is a homing missile that mostly does a good job at seeking out the nearest enemy or bullet (but can have some trouble in enclosed spaces). You can carry up to 96 missiles, which makes them a great addition to your main weapon. The Crusher is basically a screen-clearing bomb, but you can only have up to six at a time. The Barrier is a shield that you can place in any of the four directions around your bike to protect you from incoming bullets. Pressing the button changes the shield’s position one step clockwise, meaning that you can easily adapt it to each situation. The Barrier shield is always activated, and the 15 shields that you can carry are effectively its hit points: when they reach zero, you lose the barrier. The choice of the different main and secondary weapons is a welcome feature and lends itself to some nice gameplay customization.

The Motoloader bike has a health bar and you can take four hits before you die. The three top hit points are indicated by a colored bar, but when you get down to your last, it blatantly says “Panic!” (which should maybe not be taken as advice…). When you get hit, the level of your main weapon downgrades one step. You can touch walls without getting hurt, which helps the navigation of the more narrow areas tremendously. There are five different power-ups to collect: the aforementioned main weapon level-up item and the ammo for the secondary weapon, a hit point restoration capsule, a screen-clearing bomb and an invincibility device. Sadly, it is very difficult to see which power-up is which, since they all look very similar and there are a lot of bullets to dodge that pull your attention elsewhere. The second game addresses this by having a large letter on each different power up, but it’s too bad that they did not think of this for the first game. Sometimes the power-ups come in a container that you have to shoot to release the power-up, and failing to do so before touching it will hurt you, which is a pretty mean design choice.

You can select the speed on the fly with the Select button, which is a nice feature (also seen in other PC Engine titles such as Soldier Blade and Gate of Thunder). Most of the time, this is a fast-paced game free from slowdown that is very satisfying to control. There are six stages in total, each with a number of substages. While the number of stages is on the brief side, this game more than compensates for it by its difficulty. The health bar and unlimited continues does make the challenge more fair, but you will probably need to do a good share of memorization to be able to get through the stages and find the best strategy to do so.

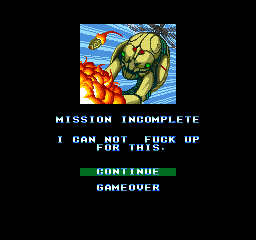

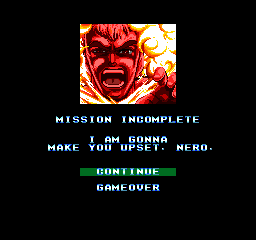

Speaking of dying, Download is somewhat infamous for its foulmouthed Engrish death screens. There is a unique death screen message for almost every substage, and they all show you dying to one of the bosses of that stage. The most infamous one comes from Stage 1-2 and conveys such a frustration that only the F-word can suffice. Sure, a Japan-only game that is mainly written in Japanese cannot be blamed for trying out some “cool” English phrases, but as people have pointed out in the past, it seems like they took their idea of the English language from 1980s Hollywood action movies and never bothered to check if any real person speaks like this. Syd does however speak in a non-polite, young-man Japanese in the cutscenes, and in this light the Engrish seems more understandable, but this is clearly an example where cultural nuances do not translate directly over the language borders.

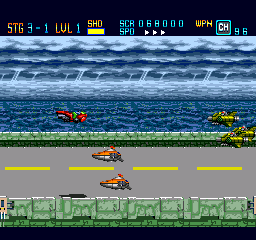

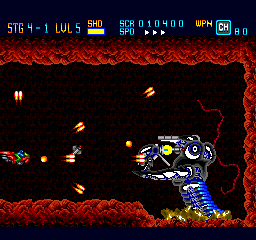

The abstract cyberdiving levels are also worthy of a mention. They take on a very 1990s Virtual Reality style with psychedelic backgrounds and enemies that are mainly textureless geometry, and somehow Syd has to battle enemies with his bike here as well just as in the real world. The enemies here tend to move in more abstract patterns and enter the screen from all different angles, which changes the strategy needed to make it through these levels compared to the rest. The bosses in these stages are viruses that Syd “deletes” by blowing them up with his bike. However, cool and central to the plot as this jack-in idea is, it is actually only used twice in the game, which is a big shame. Their abstract nature does make them a little hard to place in the story unless you can understand the Japanese dialogue.

Unlike the Super Famicom and Mega Drive, the PC Engine hardware only allowed for one single background layer, which means that software methods had to be used to if a developer wanted to implement parallax scrolling effects. There are a few games that do parallax impressively well on this system (e.g. Gates of Thunder and Air Zonk), and Download also deserves credit for how well it manages to pull it off. In the cyberdiving stages there are up to seven layers of absolutely smooth parallax with vertical layering. The PSG music is a nice listen for the most part, and the title track that plays when the game is powered on is especially good.

The cutscenes do a good job of presenting Masaomi Kanzaki’s character designs, which are excellent. The cover should also be praised for setting the tone from the start; I mean, who would not want to play as a character with that smirk? However, it should be noted that the cutscenes are lengthy and are mostly presented in dialogue. The story is much more involved than you’d think of a game of this time and genre, and you will need to have good Japanese reading comprehension to be able to follow all the twists. It doesn’t help that most of the vocabulary is cyberpunk specific – such as large corporations, circuits, cerebral nerves and computer terminals – and rich in kanji. For some reason there is a lot of American football terminology in katakana in the script as well: e.g. quarterback, touchdown, first down. The best way to try to grasp the story if you cannot read Japanese is to look at the English summary at the weapon select screens that preface every new stage.

Although Download is a solid experience throughout, the game struggles to keep up with the high stakes that are set in the excellent first stage. You can wonder if the developers deliberately made the game difficult and only really polished the first stage, which would be the part of the game people would see the most. It seems like the best parallax effects were saved for Stage 1-1 and the abstract stages and only sprinkled in some of the other stages. Enemies and bosses are well designed for the most part, though; it is just that the overall presentation never reaches the same level as the first stage. These small gripes aside, Download is among the better Japan exclusive shoot-em’-ups on the PC Engine, and should be a must-play for new and old fans of the system.

Links and further reading

Alfa Systems’ old Japanese web page that list them as the developer of the Download games:

https://web.archive.org/web/20070505011701/https://www.alfasystem.net/kaisya/games.html

Two Japanese Wiki pages that have a good amount of information on the game:

https://www26.atwiki.jp/gcmatome/pages/217.html

Racketboy’s cover of PC Engine exclusive shoot-em’-ups that discuss both Download games:

http://www.racketboy.com/retro/the-turbografx-16-pc-engine-shmup-library-pt-1-exclusives

The whole script of the game, transcribed by the author of this article while researching the story bits (there are a lot of highly specific kanji in the script, and this document makes them easy to look up in a dictionary):

https://scentoftheobscure.blogspot.com/2019/03/transcribed-script-for-download-1990-pc.html

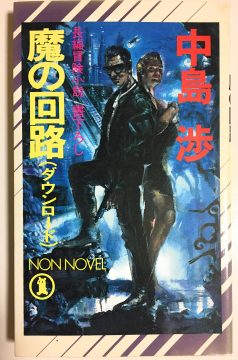

Ma no kairu (Download) / 魔の回路(ダウンロード) / Devil’s circuit (Download) – Novel (1990) – ISBN 978-4-396-20328-3

In July 1990, just a couple of weeks after the release of the first game, a light novel set in the Download universe was released to expand the story of the game. It was written by Wataru Nakajima and was published by Shodensha in their (to an English-speaker) peculiarly named Non Novel label. According to the Japanese Wikipedia entry, the Non in Non Novel is supposedly meant to invoke a feeling of going beyond the established novel format, and should not be interpreted as “unoriginal” or “non-fiction” (a genre of its own), as one might think at first…

Some sources claim that the two Download games are based on this novel, which would explain why they are so heavy on story, but this is difficult to confirm since information on this book is scarce even on Japanese web pages. Most Japanese PC Engine fan pages that even mention this book don’t say much more than that it was part of the Download media mix, but it is clear that Nakajima was involved in both of the games, according to their end-credits. From what can be pieced together online, this book was never reprinted or re-released (it is a niche title) and getting hold of the text would require searching for it in Japanese second hand bookstores. What can be found, however, are pictures of the cover and the story summary. Since there is not so much else to go on, here follows a rough translation of the back cover copy:

“Lured by a mysterious man, Sid came to a bar in New Kabukicho to learn the truth of the death of his lover. However, the inside of the bar was turning into a sea of blood, and Sid was soon shot at by a sniper. By now, it was certain that the death of his lover was part of a larger conspiracy. The year is 2099. “The Association”, the corporation managing a highly developed computer network, hired people who could connect their brains to computers to investigate accidents that had occurred in the network. Sid’s lover was one of hired. As Sid’s battle begins, surprising facts will be exposed, including the identity of the mastermind behind all this.”

It is of course impossible to judge from a back-of-the-cover summary, but the tone of this novel does seem to go in a slightly different direction than the original game. Also, the ominous corporation is now called “The Association” (協会) rather than “The Company” (会社) as in the original game. This may be a minor change, but may also be a foreshadowing of the many tonal shifts that we will keep seeing as we go onward in this franchise.