- Dragon Quest (Introduction)

- Dragon Quest

- Dragon Quest II

- Dragon Quest III

- Dragon Quest IV: The Chapters of the Chosen

- Dragon Quest V: Hand of the Heavenly Bride

- Dragon Quest VI: Realms of Revelation

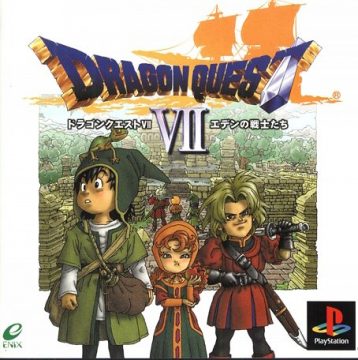

- Dragon Quest VII: Fragments of the Forgotten Past

- Dragon Warrior VIII: Journey of the Cursed King

- Dragon Quest XI: Echoes of an Elusive Age

- Slime Mori Mori Dragon Quest

- Dragon Quest Heroes: Rocket Slime

- Slime Mori Mori Dragon Quest 3

- Dragon Quest Heroes

- Dragon Quest Heroes II

Five years is a long time in the world in video games – it’s basically the entire span of a console generation. That’s also the length of time between Dragon Quest VI‘s release on the Super Famicom and Dragon Quest VII‘s release on the PlayStation. Though long delayed, it marked the first (and only) entry in the series on Sony’s 32-bit platform. In many ways, it’s an expansion on the ideas laid down by its direct predecessor, focusing on strong vignettes and an expansive job system, though in that way, it both improves on and exacerbates its issues.

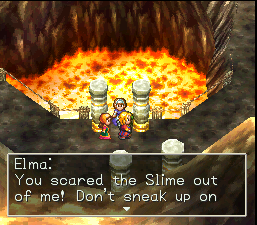

At the beginning of the game, the world of Dragon Warrior VII is a lonely, dismal place. Our heroes inhabit a lone island in the middle of a vast ocean, wondering if there’s any other life on the planet. That is, until they stumble upon some ancient ruins that transports them back in time. By traveling to the past, you’ll find different societies under all kinds of turmoil – monsters, exploding volcano, war, etc. After saving them, these rescued islands will appear in the present. One by one, you’ll reassemble the pieces of a broken world, and battle the evil force responsible for it all.

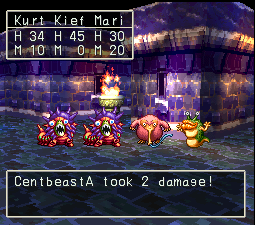

Characters

Hero

The main character – known as “Arus” in the official manga – is the son of fisherman in the town of Fishbel, and sort of an average kid who stumbles upon to something far greater.

Kiefer

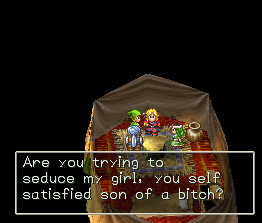

Kiefer (also known as Keefa) is the prince of the only kingdom in the world. Being a teenager, he’s not one to listen to his father, and rather takes off from his royal duties to hang out, womanize, and go on adventures with the heroes. He’s your primary physical attacker in the early stages of the game.

Maribel

A young lass from Fishbel. Like most video game heroines, she’s has something of a love/hate relationship with the hero, making her something of a tsundere. Naturally, she’s focused on magic.

Gabo

Gabo used to be a wolf cub, until a curse turned him into a human child. Eventually through some crazy magic, he obtains the power of speech, although he’s still not very good at it.

Melvin

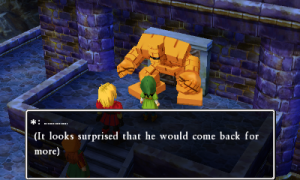

This old knight once fought beside God himself. Too bad he was encased in stone afterward. Once you awaken him, Melvin will once again join your party to fight for the greater good.

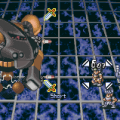

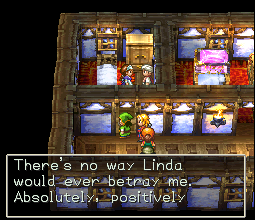

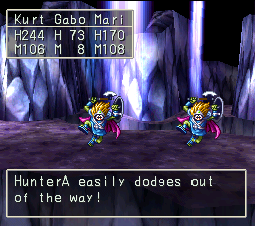

Dragon Warrior VII was developed by a studio called Heartbeat and is the first title in the series to use 3D graphics. All of the backgrounds consist of polygons, allowing you to rotate the camera in most instances, while all of the characters still consist of 2D sprites, similar to Xenogears. Given how long this game was in development, it looked pretty dated even when it came out in Japan in 2000. The character sprites actually look worse than Dragon Quest VI, and the landscapes – especially in the battle scenes – are pixellated and generally not all that attractive. The package comes with two discs, but the computer rendered cutscenes – also extremely ugly – are pretty rare, and it’s a bit hard to tell exactly what’s filling up on that space, because the music is sequenced, and there are no voices at all. The Dragon Quest games have never been about fancy graphics or sound, but it would’ve been nice if the developers took some advantage of the larger medium or more powerful hardware, especially considering it came out late in the PlayStation’s lifespan.

For instance, one scenario in the past involves a village where the humans have turned into animals, and the animals turned into humans. As expected, you find the evil villain responsible for the curse, and seal him away in a tomb. Come back in the present, and you’ll find that the villagers put on animal costumes during a festival in remembrance of their ancestor’s tribulations. You can also revisit the tomb of the sealed monster, who’s reverted into a powerless human during his imprisonment, and jokes with your heroes about how pathetic he’s become.

In another one, you’ll travel to the past and meet up with a secluded inventor, who’s so distraught over the loss of his lover that he builds a robot and names it after her, in hopes that he would have a companion that would live forever. When you visit them in the present, you find this distraught robot trying to give nurse her master back to health, unaware that he’s long dead and is little more than a pile of bones.

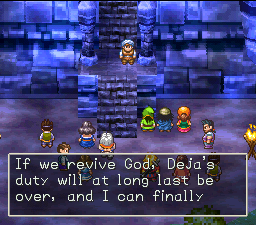

The plot eventually blossoms into an old story about God and the Demon Lord, who destroyed themselves in their conflict. It turns out God isn’t dead, He’s just resting. You can choose to fight God at the end of one of the bonus dungeons at the game, but it’s not the whole silly “God is evil” thing that afflicted a number of other 32-bit RPGs like Xenogears of Final Fantasy Tactics. Rather, it’s just a friendly challenge from theAlmighty – and he even looks like a pretty lovable chap.

PlayStation

Most of the stories are unrelated to one another, although a few are connected in small ways. It is pretty cool to see the overworld grow from a tiny piece of land, to a small cluster of islands, to a huge series of continents as large as any of the previous games. By and large, it’s not as involving as Chrono Trigger for one main reason (and was one of the most confusing issues in Dragon Quest VI) – there’s no real visual distinction across time periods. The past often looks just like the present, except the past is usually encased in perpetual night or something similar (like Dragon Quest VI, there’s no day/night cycle – time just changes depending on the plot.)

The major problem with the game, though, is that it suffers from absolutely glacial pacing. The first segment of Dragon Warrior VII is spent running fetch quests and exploring one long, very boring dungeon (at least in the initial PS1 release). According to later interviews, Yuji Horii was inspired by Myst, which focused solely on puzzle solving in an isolated environment. But for an RPG, it feels way too drawn out, especially seeing how you won’t even get into a fight until roughly two hours in. The plot doesn’t even start properly until you’re a good chunk through the game, and you won’t even get to mess around with the class system until roughly fifteen hours in.

And even once the main story has kicked into gear, there’s still lots of senseless backtracking, because Dragon Warrior VII probably has the highest proportion of fetch quests of any JRPG in the history of JRPGs. Every chapter works like this: in order to warp through time, you’ll need to hike through several screens to get into the lower chambers of the ruins. After teleporting and discovering the crumbled society you need to save, you’ll need to figure out some kind of resolution. Many times, this involves transporting back to the present, hiking back to the overworld, finding some object or person to help you out, hike into the depths of the shrine, transport back to the past, and then proceed.

And that’s only half of it. Once you’ve saved a land in the past, you need to revisit it in the present. In order to open up new lands, you need to search for broken elemental shards. In some instances, this involves scrounging through the same dungeons you’ve already conquered, or obsessively rummaging through every bookshelf, dresser and treasure chest. Even with the transportation spells and other shortcuts that the game gives you, there’s really no reason for all of this running around, except to maybe pad out the game’s length. Dragon Warrior VII is one of the longest of the series, and certainly the largest of any PlayStation era RPG.

There is some rationale to this. Over Dragon Quest VII‘s protracted development period, Square had released three whole Final Fantasy games for the PlayStation. Since this was meant to be the only Dragon Quest of the console generation, it does make sense to provide a very long length, to sort of make up for lost time. But on the other hand, it brings up the question of whether Dragon Quest is really suitable for a game this long. The basic visual style doesn’t really change over the course of the game – most of the towns, dungeons, and characters all look pretty similar, and the music eventually sorta blends together. Even Dragon Quest VI began to wear out its welcome near the end of its 30+ quest, but considering that it’ll take most gamers over 100 hours to see this one to completion, it really requires a lot of patience and dedication.

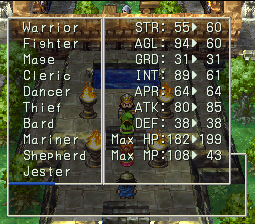

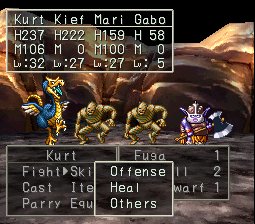

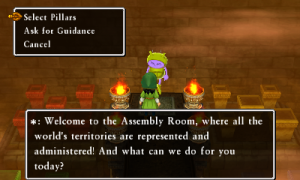

Along the way on your massive journey, at least there are all kinds of ways to train your party members, as Dragon Warrior VII utilizes a class system similar to Dragon Quest VI. Once you reach the Dharma shrine, you can assign jobs to any of the characters, and they level up in pretty much the same manner. However, there are more job classes than its predecessor, with skills spread pretty thinly across them, resulting in even more bloat. On the plus side, there are now “hybrid skills”, unique abilities which are obtained by mastering two different classes. For instance, mastering the fighting class and the dancer class will grant you the powerful SwordDance ability. There are also three third-tier classes, compared to the single Hero class of Dragon Quest VI, and these require the mastery of multiple advanced classes. It takes a lot of effort, but the powers of the God Hand and Summoner can be pretty devastating. Additionally, certain monsters leave “hearts”, allowing you to equip them as jobs and level them up. Like the standard classes, if you level up enough monster classes, you can eventually unlock more classes without having to find more hearts. When you master a monster, that character changes appearances into that creature. This replaces the monster collecting system of Dragon Quest V and VI. There are only a total of six characters in the game, and they come and leave as the plot dictates, so the caravan has been removed. This aspect itself is also annoying, because it’s a pain to level up your character skills, then have them leave. They don’t gain any skills when they’re away either.

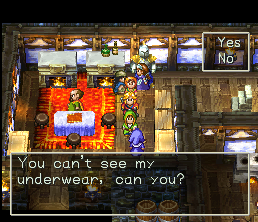

There’s also a brand-new subquest called the “Immigrant Town”. Early in the game, you come across a deserted island. As you speak to various people throughout the game, you can convince them to move and join your village. It’s somewhat similar to the castle building in the Suikoden games. However, the type of people you collect will drastically change the town itself. Also new in Dragon Warrior VII is the “Talk” option, which allows you to converse amongst your party members to discover your next goal. However, they aren’t exactly a chatty bunch, and most of the time are just “lost in thought”. The fashion contest is back too, although it takes other stats into account, rather than just your “style”. Also new is the Monster Book, which basically just acts as a bestiary of all the bad guys you’ve fought.

One of the upsides to the simple graphics is that the game avoids one of the biggest problems of early CD RPGs – the load times. Dragon Quest VII uses newly developed streaming technology that preloads essential data and ensures there’s almost no load times once the game has started. While it helps ensures that the pacing is similar to the cartridge games, it was also quite buggy, at least in its initial Japanese release, and it was often prone to crashing.

Dragon Quest VII became the highest selling RPG on the PlayStation when it came out in Japan, but it didn’t quite meet with the same success when it was released in America over a year later. Although RPGs had become more popular with the release of Final Fantasy VII four years earlier, Dragon Warrior VII‘s dated visuals and gameplay did little attract an audience, beyond those who were familiar with the game back in the NES day. This was especially true considering it came out a year after its Japanese release, by which time the PlayStation 2 was on the market, making it feel even more dated.

It didn’t help that it didn’t feel like there was much effort put into the localization. All of the text is still monospaced, the English font is ugly, and the battle windows weren’t expanded to allow for names longer than four characters, so they’re all abbreviated. This is the sort of thing that was expected back in the 8-bit era, and looks positively terrible for a 32-bit game. The translation is relatively consistent with the spell names from the 8-bit era, including spells like “Healmore” and “Hurtmore”, although most of the writing is pretty bland.

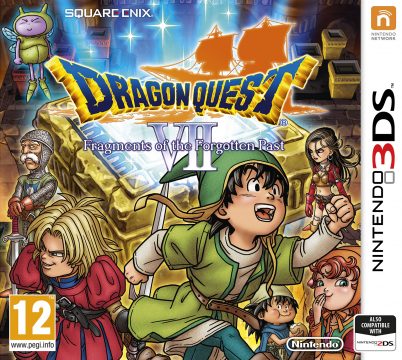

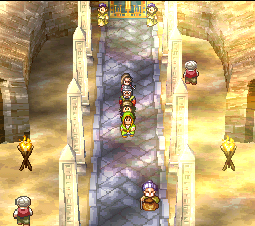

In 2013, Square-Enix remade Dragon Quest VII for the 3DS. Developed by Arte Piazza, the company behind many of the previous Dragon Quest remakes, it completely revamps the game in full polygonal 3D. It’s somewhat similar to the PS2 version of Dragon Quest V, though with significantly better visuals. It’s not as nice looking as Dragon Quest VIII but it still looks decent, and it’s easier to relate to some of the characters, particularly the NPCs, when they aren’t just tiny sprites. The game is primarily viewed on the top screen, with the bottom used as a map.

Keeping with Dragon Quest IX, random encounters are gone, and enemies are now visible on the field. This works fine in the overworld, but many of the dungeons have such narrow corridors as to make many battles impossible to avoid anyway. Plus the rate of enemy spawn is so frequent that, in some cases, they battles occur even more often than regular random battles. Still, in general it helps the pacing, especially when re-exploring dungeons.

During battle, as with the later installments, you select targets from the first person, but actual combat is shown from the third person. However, here the camera just slightly zooms out and shows the heroes fighting from an over-the-shoulder perspective. Enemies are sometimes shown in different rows, but this is only for visual distinction, and doesn’t actually affect the combat. It’s a little faster than the other implementations, plus it maintains the classic feel of the older games. However, it’s still somewhat boring to just see nothing but the back of your characters. This is especially a shame, since one of the biggest additions is that your party members now change costumes based on their jobs, but you only get the full view of them when running around. In general, the menu also feels strangely sluggish.

A number of other aspects have been tweaked. The job system has changed a bit to rebalance certain skills, and remove some altogether. For certain very strong skills, they can only be used when you’re actually assuming a certain job, and cannot be permanently learned. The “Padfoot” skill was removed due to the visible encounters, but since they can become quite numerous, it would’ve been handy if it had just changed their numbers or eliminated them totally. A radar is added, to give an idea of where to find various shards. It doesn’t directly pinpoint their location on the map, but rather is just glows whenever you’re near one. A story synopsis has been added too. The ability to talk among party members in combat has been removed, but this was largely useless to begin with. But lots of new party dialogue and NPC dialogue has been added, which fleshes out the party members much more than they were before.

The prologue isn’t as long as the PS1 version, seeing as nearly all of the puzzles from the shrine have been removed. A new character, sort of a fairy/insect thing, has been added to the shrine to explain the functionality of the tablets too. The damage caused by the flood to the town of Hermelia (known as Wetlock in English) was changed to be not nearly as severe. The game was released not long after the Tohoku earthquake tsunami and this was changed in sensitivity to those real life events. Similarly, one of the skills that was removed was the Tsunami ability.

The Immigration Town has been changed to something more similar to the DS version of Dragon Quest IV. Dubbed Monster Meadows in the English version, it’s basically something like a monster preserve. There’s a random chance that defeated monsters will give up their evil ways and join your village, which turns them into humans. Throughout the adventure, you can find plans to build new additions too. Finding monsters can give you different types of plates, which in turn opens up optional dungeons (most based on reconstructed versions of other dungeons). You can also trade these monsters with other players using StreetPass, or over the internet.

Most of these changes were done to make the game less tedious, or fix some of the rebalancing issues, and they definitely make for a better experience. That being said, you can’t really fix Dragon Quest VII‘s more issues – its bloated length – without cutting out some of the more boring parts, and remakes that remove stuff tend not to go over well with players. Despite being widely hated, and not having much of an effect on the overall plot, there are still fans that prefer the puzzle shrine at the beginning of the PS1 game, after all. So in other words, the pacing is better than it was before…but it’s still pretty long, and it still drags on.

Plus, some of the other remakes add in various aspects to make it worth replaying, particularly new characters, like the Psaro chapter of DQIV, Debra in DQV, or Red and Morrie in DQ8. There are a few short downloadable chapters that expands on some of the NPCs, but otherwise, there’s not really much new with this remake, at least enough to justify sinking another 100 hours into it if you’ve already played it on the PS1 (unless you’re a really big Dragon Quest fan anyway). While some of the changes will likely be questionable for long time fans, the 3DS version is probably the best way to go if you haven’t played it before.

After its Japanese release, it seemed like Square-Enix was uninterested in localizing the game outside of Japan. While Dragon Quest IX was a huge success for the DS in North America, the subsequent DS ports and spinoffs met with diminishing returns, to the point where Dragon Quest Monters Joker and Dragon Quest VI were regarded as flops. Plus, the script for the game is incredibly long, and would need to be completely redone, at a significant expense. But after sustained demand from fans – Square specifically referred to the French-speaking community – it was finally released in North America and Europe in 2016, three years after its initial release.

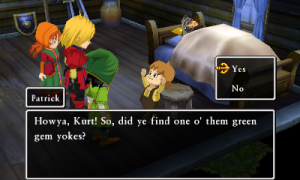

Much like every Dragon Quest game after VIII, the dialogue is heavily localized, with many of the towns speaking in various accents, many of the monsters given silly names, and many towns and locations being renamed. The translation is legions beyond the PS1 version, which plays up the game’s strengths, both in making the heroes more likable and making the vignettes more emotionally resonant. Since the PS1 version was originally released in English, it makes for a good comparison point to show how much stronger the game feels with the greatly embellished writing, comared to a rather boring, literal translation. It also gets a new subtitle: Fragments of the Forgotten Past.

One unfortunate downside – the Japanese version featured live orchestrated music, but the overseas versions replaces it with sequenced music, like the smartphone ports of the other games. It still sounds decent, better than the PS1 version for sure, but it’s an unquestionable downgrade from the Japanese version. This seems to have happened because of licensing issues with the orchestrated soundtrack.

The smartphone version of Dragon Quest VII is based on this version. It’s mostly the same, outside of the sequenced music, though it removes the visible enemy encounters and goes back to random battles, since dodging enemies on a touch screen is difficult anyway.

Comparison Screenshots

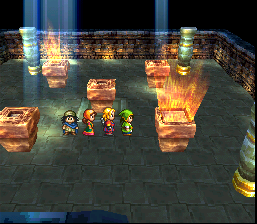

Town

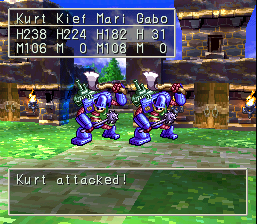

Battle

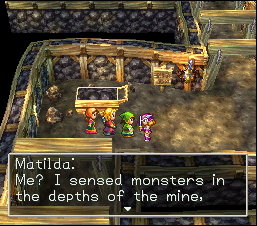

Overworld