Frank Herbert’s Dune novels count themselves among the classics of science fiction, and have spawned a number of spin-off novels, board games, a film adaptation, two TV miniseries, and several video games. The first among these, simply titled Dune, was published in 1992 after a troubled development period. The foundation for Dune was laid by Martin Alper, founder of Mastertronic, the later Virgin Interactive. Alper acquired the rights to adapt Dune digitally from Universal Pictures, whom in turn had gotten them after Frank Herbert’s Dune film adaptation had bankrupted its production company.

The work on Dune was started in 1989 by a French developer assemble named “Cryo”, the later Cryo Interactive Entertainment. At this point, all agreements between these developers and Virgin Interactive remained informal. In 1990, after a change in management, Virgin Interactive decided to cancel the game, neither satisfied with Dune’s aesthetics nor convinced that its mix of adventure and strategy gameplay would succeed. Instead, they handed the license to Westwood Studios, who would use it to develop Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty, the grandfather of all base-building real-time strategy games.

However, the Cryo team continued to work on Dune in secret. Shortly thereafter, Sega acquired Virgin Interactive’s European operations, but not the Dune license. Now, Virgin Interactive’s American management realized that the game was still in development. After a meeting with Alper, the developers management to convince him to reverse the cancellation of the project. Nevertheless, the development of Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty continued, and the game, while nominally a sequel, was co-developed alongside Dune.

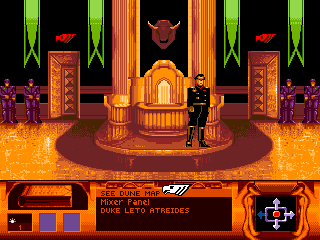

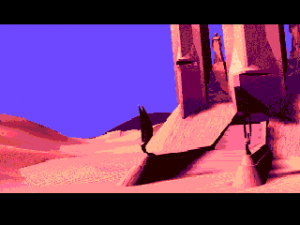

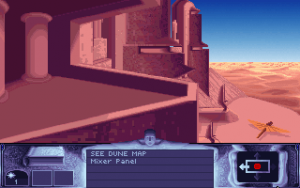

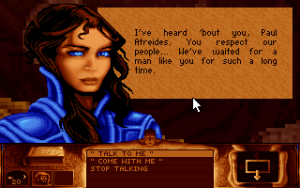

Dune is primarily inspired by the original Frank Herbert novel, but lifts some aesthetics from the David Lynch film adaptation. A Dune prototype shows Paul Atreides, the protagonist, to look quite different in his original incarnation. In the release version, he looks clearly like Kyle MacLachlan, who played Paul in the film adaptation. The American box art of the DOS version and the Sega CD box art even feature pictures of MacLachlan as Paul. Feyd-Rautha, one of the three main antagonists, also had his appearance slightly altered, but resembles Sting, his actor in the film, both in the prototype and the release version. The other characters are true to their general description from the novels. One exception is the Emperor, who no longer is a middle-aged ginger but some hideous squid-faced, bug-eyed humanoid instead. Directly lifted from the film is the introductory speech by Princess Irulan, daughter of the Emperor – albeit in low resolution.

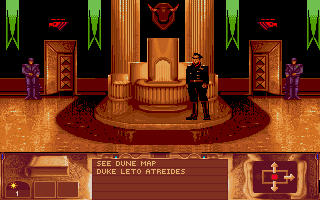

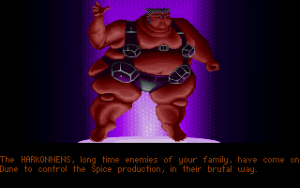

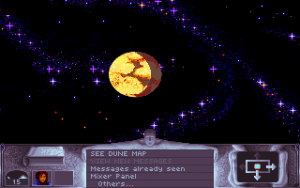

Dune is a strategy game, just like its sequel. It does, however, mix its strategy gameplay with adventure elements, exploration, management, and some combat. The player takes the role of Paul Atreides, son of Duke Leto Atreides. Like its source material, the game is set in a post-technological future in which humanity has colonized many planets. Safe travel between the planets is possible due to the Spice melange, a substance only found on the desert planet Arrakis, also known as Dune. Spice allows ship navigators to take a glimpse at the future, which in turns enables them to perform hyperspace jumps safely. This makes Spice the most valuable substance in the universe, and Dune the most valuable planet in the Imperium. Right now, the planet is managed by House Harkonnen, bitter rivals to House Atreides. However, the Emperor of the Known Universe has permitted House Atreides to move to Dune, provided they pay him a regular Spice tax.

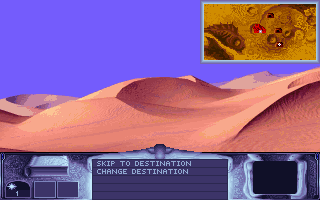

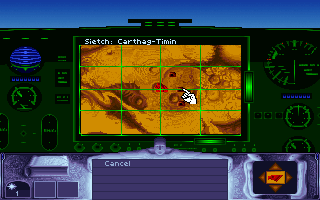

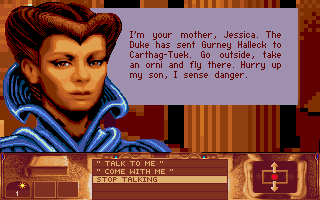

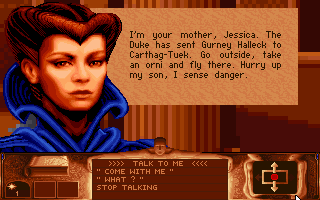

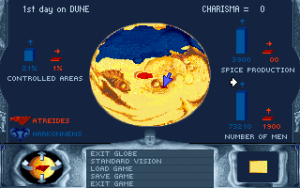

Initially, Dune is strong in the adventure department. As Paul, the player talks to and gets to know the members of the Atreides household, learns how to fly between locations in an ornithopter, discovers some secrets in the Atreides palace, and earns the trust of the Fremen. The Fremen are the natives of Dune and live in cave-like sietches all over the planet. Once Paul has befriended a tribe of Fremen, they can become either Spice miners, soldiers, or later ecologists. Spice mining is the most important of these three occupations. Spice is needed to buy equipment and to pay off the Emperor. Should Paul fail to make a Spice payment, the Emperor will send his elite guard to kill him. Over the course of the game, the Emperor demands more and more Spice. However, the total amount of Spice on Dune is limited, putting a hard limit on every playthrough of the game. All of this happens in real time – Dune is no a turn-based game.

After the initial adventure segment, the strategy and management parts of the game become more important. In order to expand, Paul has to find new sietches and recruit more Fremen. There are dozens of sietches on the map, but finding them is not easy: Paul needs to fly an ornithopter or ride a giant sandworm between locations, hoping to simply run into one. If accompanied by an ally, said ally will point out when a sietch is nearby. Likewise, NPCs sometimes hint at the location of a sietch during conversations. Nevertheless, finding sietches can be a bit tedious and time-consuming. Luck is involved as well: not all Fremen groups are equal in size. The larger a group, the better they will perform their task. In addition to that, Paul can equip miner Fremen with Spice harvesters and ornithopters to increase their harvesting speed and protect the harvesters against the ever-hungry sandworms. Likewise, groups of soldiers can be equipped with knives, laser guns, sonic weapons (lifted from the film adaptation) and finally even nuclear weapons. The last group, ecologist Fremen, merely need time and water to do their job. This equipment can either be found, taken from Harkonnen soldiers, or be bought from smugglers.

Thankfully, Dune equips Paul with psychic powers. These can be used to communicate with Fremen over a long distance and cut travel times significantly. Over the course of the game, Paul’s charisma and his powers increase, allowing him to recruit even skeptical Fremen tribes and finally consume the water of life, a liquid produced by a drowning young sandworm. If he takes it too early, Paul perishes, but taken at the right time, it allows him communicate with any tribe on the planet, no matter the distance. However, a strong economy alone is not enough to defeat the Harkonnen. The Harkonnen palace has to be taken to claim the entire planet. That is easier said than done, as the Atreides start with no troops. Thankfully, Thufir Hawat, advisor to the Duke, is there to train the Fremen to become soldiers. Once trained, a tribe of soldiers can be sent to conquer a Harkonnen-occupied sietch and liberate the enslaved Fremen there.

The combat in Dune is not very engaging. The number of tribes that can be sent against an enemy fortress is capped, but there is never a reason not to send the maximum number of tribes – leaving one slot for the newly liberated tribe. Spreading out troops is not advised, as losing a battle means losing a sietch and losing everyone who currently occupied that sietch. Instead, Dune encourages the player to concentrate their best troops equipped with the highest-tier equipment and simply move from Harkonnen sietch to Harkonnen sietch with a single huge army. Due to the cap, it is best to turn the most numerous tribes into soldiers, maximizing the number of soldiers that can attack a sietch at once. Paul can join the battle himself, which comes with a risk. Should he lose the battle, he will be killed, and the game ends. After a successful battle, the Fremen turn the newly conquered fortress back into a sietch. Additionally, the commanding Harkonnen officer can be interrogated and may reveal some information. For some reason, Harkonnen officers looks rather samurai-like. Interestingly, this is more in line with the presentation of the Harkonnen in Frank Herbert’s Dune, the 2000 Sci Fi Channel adaptation. That said, there is no evidence that the series creators took inspiration from this game.

Dune offers a second method of driving away enemies. After Paul has made contact with the goblin-like Liet Kynes, a planetologist, Kynes can teach the Fremen how to grow plants even under Dune’s harsh climate conditions. After a wind trap to collect moisture from the air has been constructed, the Fremen start their horticultural careers. Once a sietch has been covered in plants, the Harkonen will leave it alone, as it is no longer suitable for Spice harvesting. This sword cuts both ways – Paul and his Fremen will likewise not be able to harvest Spice there anymore. Unfortunately, growing plants takes so long and becomes accessible so late that perusing this option is mostly pointless. The same is true for a couple of Dune’s other mechanics, many of which feel somewhat half-baked. Paying the Emperor requires Paul to be back at the Atreides palace, talk to his master-at-arms Duncan Idaho, go to the communications room, make the payment, and confirm it with the Emperor. It is a whole lot of repetitive clicking that adds almost nothing to the game and may as well be automated.

Likewise, searching for new sietches is as necessary as it is boring. Fast travel is available, but no new locations can be found while fast-traveling, forcing the player to watch the same travel animation again and again. Combat can be incredibly random. Sometimes a small group of Fremen defends a sietch against superior forces, other times a well-trained, well-equipped strike force fails miserably in their mission to take a poorly-defended Harkonnen fortress. Paul is able to haggle with smugglers, but there is no penalty for doing so. Thus, there is never a reason not to take the time to haggle and save Spice. Paul can have one ally accompany him, but switching out allies means leaving someone behind at a random sietch – good luck finding them later.

That said, Dune has a lot of nice touches. There are a number of different Fremen portraits, with Fremen from northern Dune being fair-haired and Fremen from southern Dune being dark-haired. All characters look a bit blocky, which gives Dune a distinct and interesting look. The mix of adventure game and strategic management simulation is somewhat unique and, while not entirely true to the source material, fits the Dune universe well. The soundtrack, composed by Stephane Picq, is excellent, which is probably why it was rearranged and later released separately under the name Dune: Spice Opera.

Dune was released for MS-DOS, Amiga, and Sega CD, with the differences between the versions being superficial and largely confined to some graphical changes. The Amiga and Sega CD versions lower color palettes but still manage to look pretty decent. The Sega CD version also has certain limitations with regards to controls, as the mouse interface was removed. Instead, the cursor will cycle through whatever interface elements are currently present on the screen, sometimes in seemingly (and frustratingly) arbitrary order. Mega Mouse support is not available, and neither is smooth world map scrolling. The IBM PC version comes on floppy disks or CD; the CD version, just like the Sega CD port, has an animated title screen, animated travel sequences, and voiced dialogue. No matter the platform, Dune remains a solid adaptation of its source material, though it is also a limited one. Its biggest failure is probably being the formal predecessor to Westwood’s Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty, which revolutionized the strategy genre singlehandedly. Thus, it suffers the same fate as the original Street Fighter: being a game known for not being that game that everybody knows.