|

Page 1:

Intro

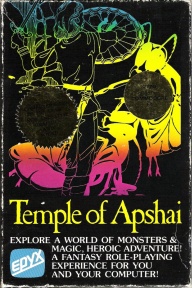

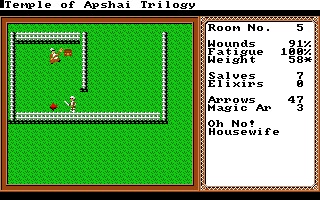

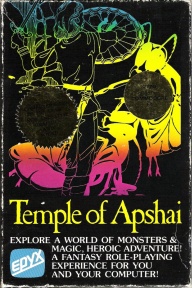

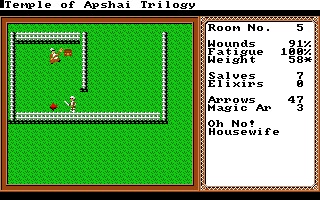

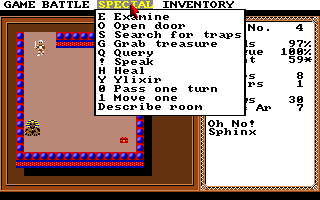

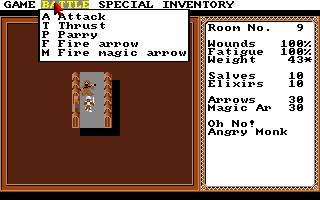

Temple of Apshai Trilogy

The Datestones of Ryn

|

Page 2:

Morloc's Tower

Hellfire Warrior Trilogy

Sorcerer of Siva

|

Page 3:

StarQuest Series

Crush, Crumble & Chomp!

Gateway to Apshai

|

|

Back to the Index

|

by derboo

|

Any gamer with an interest in the history of her or his hobby has heard of Wizardry. Ultima will ring a bell, too. Even though both franchises' main series are long discontinued, their legacy is kept alive. Japan consistently churns out new spin-offs to Wizardry almost every year, while Ultima Online is still the oldest commercially used MMO, with most remaining subscribers once again in Japan.

Namedropping Dunjonquest, on the other hand, is more likely to cause people turn on their browser's spell check. Only the most old school will remember that label adorning the box of the first commercial hit RPG ever. Automated Simulations, who later renamed themselves to Epyx, created and published Temple of Apshai in 1979, predating both Wizardry and Ultima (although we'll likely never know for sure if Akalabeth was released earlier). The game was such a huge success that it entailed more than 10 sequels, mission packs and spin-offs within few years. How come that the one has all but vanished from gamers' collective memory while its competitors can be sensed in most electronic RPGs until today, both in western and far eastern tradition? Before trying to answer that question, let's have a partial look at the roots of computer RPG gaming and the early history of Epyx, formerly known as Automated Simulations.

Computer-assisted fantasy role playing started as early as the mid-1970's. Dungeons & Dragons had just been released in 1974, and the more nerdy students at several technical universities were often prone to "abuse" the institutes' mainframe computers for their new hobby. This didn't stop at mere tools for the dungeon master, though, soon inventive role players came up with ways to cram an entire portion of the experience into the computers — the dungeon crawl computer game was born. Programs like pedit5 (first version 1974), dnd or Moria (1975) followed Dungeons & Dragons in its rise to popularity and were eagerly exchanged among students, in the case of Moria even used for cooperative online play.

In analogy to the history of CRPGs overall, Epyx' story also begins with Dungeons & Dragons. Jim W. Connelley had bought his Commodore PET computer originally to help him manage his D&D sessions he led as a dungeon master. Of course a computer for home use was no marginal investment in the 1970's, and so he decided to produce and sell a computer game to get back his money's worth. His partner should become Jon Freeman, a player at his D&D game and a board- and war game journalist/creator himself. Together they first conceived the SciFi war game Starfleet Orion and released it around christmas 1978 as Automated Simulations. A sequel called Invasion Orion followed the next year, but soon their passion for Dungeons & Dragons encroached on their new found profession.

Similar in structure to many of the mainframe dungeon crawls but with unequaled complexity, yet using a (for the time) very user friendly interface and, maybe even more importantly, commercially published for home computers, Temple of Apshai was hailed by critics and gamers alike as the best game of its time. Its greatest strength were the colorful room descriptions available in the manual. Automated Simulations still presented Dunjonquest to the user as an alternative to the bothersome task of managing a conventional pen & paper RPG campaign. Therefore, the episodes were handled as modules for a common role playing system, much like adventure books in PnP circles. Every room in the game displayed a number, which could be looked up in the manual to supplement the meager and monotonous graphics with fantasies of underground rivers, collossal statues or other such peculiarities. The descriptions were no mere flavor text, though, and provided hints for hidden passages, traps and treasures.

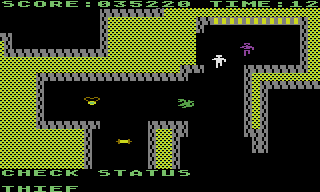

At the end of 1981, Jon Freeman left the company to form Free Fall Associates together with his wife Anne Westfall. The two as a team became known mostly for creating the board-/action game hybrid Archon. The final expansions for the major DunjonQuest games were created without his participation, but otherwise the series had come to an end. The Connelley Group, how the core development team at Epyx was then named, continued to port the games to several platforms, but the only new game to follow after Freeman's leave was Gateway to Apshai (1983), an action RPG spin-off to the Temple of Apshai trilogy. After the success of Jumpman in 1983, the new management at Epyx decided to concentrate their main efforts towards action games, which led Connelley to bid his farewell, too.

In 1985, around the same time when Epyx started to publish various ports of Rogue, they also released Temple of Apshai Trilogy, a remake of the most successful Dunjonquest mini-series. This version was redesigned by Stephen Landrum, but other than the obious graphics and interface improvements left the actual gameplay unchanged. In that form the game obviously had little hope to compete on the market with contemporaries such as Ultima IV, Wizard's Crown or The Bard's Tale and thus remained the only effort to revive the series. Dunjonquest therefore was never given opportunity to develop into more complex and refined territory with age like its early competitors did.

Yet it is not only the early discontinuation that divides Dunjonquest from its more famous rivals. It is also important to note that the series was never big in Japan (in fact, it doesn't seem like any of the games have ever been released over there) and didn't at all exert the massive influence over the JRPG tradition that Ultima and Wizardry enjoyed. Nonetheless Dunjonquest remains an important part of RPG history, even if its influence is felt more indirectly. Most of all, it proved that a CRPG could be a mainstream success, extending the genre's reach beyond nerdy TI student networks. It also paved the way for the birth of action RPGs with its pseudo-realtime combat engine.

Thanks and Sources

- Big thanks go to Trypticon over at the The Legacy community, for lots of valuable information and files concerning the less accessible ports

- The Museum of Computer Adventure Game History showcases a huge amount of scans from vintage computer game boxes, not limited to DunjonQuest; a visit is highly recommended

- Scans for many of the original manuals collected by robinsonmason at Mediafire

- Epyx Shrine (archived by The Wayback Machine)

- Epyx History at GOTCHA

- Interview with Jon Freeman and Anne Westfall from Halcyon Days: interviews with classic computer and video game programmers by James Hague; available at Dadgum games

- Ira Goldklang's TRS-80 Revived Site

- Finally, those who desire to relive the first hours of computer RPG gaming be pointed towards the cyber1 community and their PLATO Terminal Emulator

|

pedit5, the oldest known mainframe dungeon crawl

|

Starfleet Orion (TRS-80)

|

DunjonQuest Series Staff Members:*

|

Game Design:

|

Jon Freeman

Stephen Landrum (Apshai Trilogy)

|

|

Programming:

|

Jim Connelley (TRS-80, PET, IBM-PC, C64?)

Michael Farren (Apple II)

Aric Wilmunder (Atari 400/800)

|

|

Dunjon Design:

|

Jeffrey A. Johnson (Apshai through Hellfire)

Paul Reiche III (Keys of Acheron)

Rudy Kraft (Danger in Drindisti)

|

|

Graphics:

|

Tony Thompson (Apple, IBM-PC)

Michael Kosaka (Apshai Trilogy)

|

|

Illustrations:

|

Karen Gerling (Temple of Apshai)

Jonquille Albin (Ryn, Morloc)

Lela Dowling (Hellfire Warrior)

George Barr (StarQuest)

Michael Mott (Trilogy)

|

|

|

Temple of Apshai (TRS-80)

|

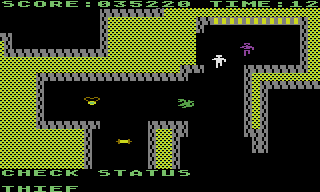

Gateway to Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

|

*A couple of names are yet missing, such as the map designers for most of the later episodes, the programmers for the VIC-20 ports as well as the various Temple of Apshai Trilogy versions. If you happen to own any of the original manuals for those games and can provide some of that missing information, please get in touch.

Temple of Apshai - TRS-80, Commodore PET, Apple II, Atari 400/800, IBM-PC, Commodore 64, VIC-20 (1979)

C64 Cover (early version)

|

C64 Cover (CBS version)

|

Manual Art

|

|

When thinking old video games, one is quick to assume a simple, 2-paragraph background story in the manual, but not so with Dunjonquest. The introductions for some of these games are almost like tiny fantasy short-stories that fill multiple pages. Especially Temple of Apshai's setting is miles away from generic "save the world, beat the boss & get the girl"-clichés that developed in later times: For generations no one has laid eyes upon the old temple of the ant god Apshai. Envied for their wealth but feared for rumors of dark rituals, shortly after their intrusion into the country its followers were driven into an underground realm centuries ago by the followers of Geb, god of the earth. Deep inside the caverns they build their city and temple, but in the end they were destroyed by divine intervention and their ruins buried under the earth.

Only recently high priest Nemdal Geb ordered the excavation of the now but legendary ruins. The temple and its riches were indeed found, but after a short time work parties in the fourth passage of the temple started to disappear, and soon the whole complex became once again inaccessible. Desperate about the decline in population and profits from the temple, the high priest himself led a party of the greatest warriors in town into the depths, only for none of them to ever return.

Temple of Apshai's rich supplemental material presents this tale to Brian Hammerhand, the iconic hero of the Dunjonquest series. It doesn't have to be him who enters the dunjons (a variant on old English / original French spelling for dungeon), though, as the game offers a rather particular form of character generation. Players can either have the game create a new character at random, or enter their own, completely at their discretion, stats, experience, inventory and all. Going with this function, Automated Simulations encouraged to carry over characters used in Dungeons & Dragons and other pen & paper RPGs. Granted, the possibilities for characters are rather limited. Dunjonquest uses a system based on 6 main characteristics, compatible with many popular PnP rulesets, but knows no races nor classes, not even magical spells. The available equipment is very sparse, as well. The import function was more useful as a savegame ersatz (when no free save disk was available, or for mistrust towards the glitchy character save routine in some versions. Tape versions didn't support saving at all.), as well as to transfer characters to following Dunjonquest episodes. It takes no connoisseur of human nature, of course, to guess that in practice it was mostly used for cheating. It should not be forgotten, though, that the game is a child of the pen&paper mentality, that puts the players in charge to make sure they confront themselves with proper challenges according to publisher reccomendation.

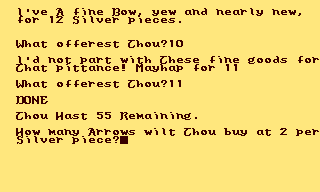

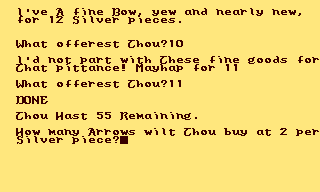

The character generation process is part of the "inn" program (early versions of the game were programmed in BASIC), which also co-functions as a shop for weapons and items (haggling is also possible) and, last but not least, a hub to enter all four levels of the temple. Temple of Apshai uses an open-ended structure, the quest merely being to plunder the temple and get filthy rich. So all the levels are accessible from the very beginning, although a fresh, uncheated character is likely to get slaughtered fast in the higher levels. Dieing doesn't neccessarily mean game over, though, as one has a chance to be rescued by one of three other adventurers. The dwarf, however, demands all gold and treasures for his services, though. The magician takes away all magical items, only the priest is content with a small donation for his sect.

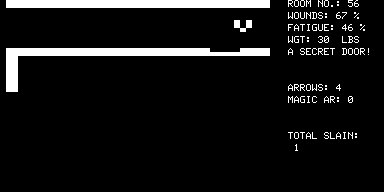

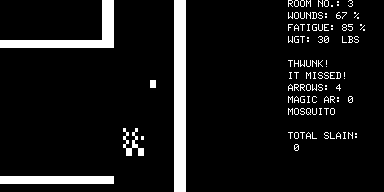

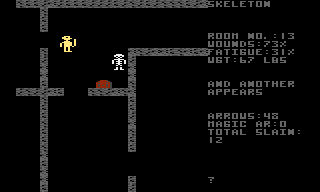

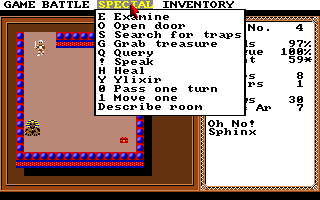

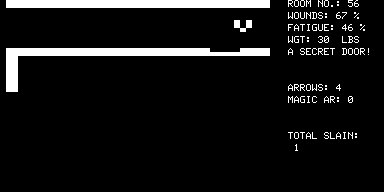

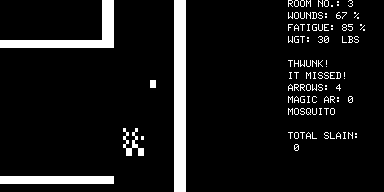

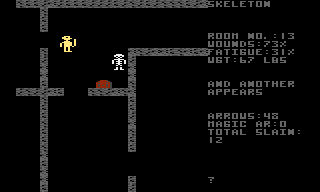

When entering the top-down DunjonMaster module for the first time, the controls are very off-putting for today's standard. The game is exclusively controlled with the keyboard, but you'll find no WASD scheme here (Wizardry actually invented that). In old-fashioned text adventure manner, "l" makes the character turn left, "r" stands for right. To move forward, one has to hit a number from 1 to 9 which determine the movement "speed", but also the amount of fatigue the move is going to cost. All other actions have their own hot keys, as well. What Dunjonquest lacks in character creation options, it more than makes up for in the extraordinarily satisfying dunjon crawls. The game makes very meaningful use of the six base statistics, so a high intuition makes the hero more likely to find hidden doors and traps, for example. With each move the character grows tired based on carrying weight, strength and even the severity of wounds. When the fatigue rating drops to zero below, the adventurer cannot move or fight until recovered, leaving him an easy pray for near beasts. The fatigue system adds a nice extra layer of tactics to the game and is much more well thought out than the need to carry food around and consume with every step in many early RPGs.

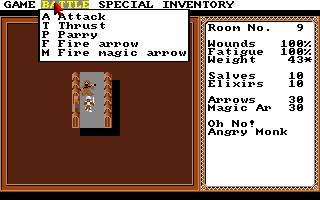

The core of the game is made up by the inventive (in 1979, mind you) combat system. Besides the standard attack, it's also able to thrust towards enemies for a damage bonus, but this comes by the cost of leaving oneself more open for counter attacks. Parry on the other hand has the opposite effect and is also valuable to conserve stamina. But ressourceful adventurers try to stay at a distance and penetrate their more dangerous foes with arrows. Monsters, however, don't wait for you to carefully think through your strategy. Not forever, anyway. They move in a kind of active turn based intervals, which can be set between three levels at the beginning of the game. After each of your moves they definitely strike, though, and they even get a final move after being hit by a deadly stroke. So there's no time to be lost, but not much room for careless decisions, either. It's even possible to try and talk monsters out of the fight, or one could just run away, as they never leave their room, but stay there lurking for forgetful adventurers on their way back out of the dunjon. The combat in Temple of Apshai was definitely much more complex and thrilling than anything seen before in the mainframe proto-RPGs.

There is no target, no finish line, other than making it back to the entrance alive and with as much loot as possible. (Level 4 holds an unique enemy that could be viewed as a boss of some kind, but it doesn't end the game or anything and can even be skipped altogether by exploiting a glitch.) When returning to the inn, the games' open design becomes a bit much, though, as it honestly asks players to calculate the value of their treasures themselves and enter their total amount of gold by hand. At least the game manages the gained experience points, although it doesn't count character levels and the actual effects of gaining experience are kept obfuscated.

Dunjon levels and characters can be saved separately, so there's the choice to either conquer them over multiple sittings or have them reset for future raids. Once again it's up to the players to pick their challenges. When aiming to clear out a level in one go, skillful ressource management is imperial. Weapons and armor break and can only be replaced by what is found in the dunjon, an inventory for spare equipment doesn't exist. Valuable arrows and healing salves can be carried in limited quantity only. If it wasn't for the fixed dunjons, Temple of Apshai would have been an almost roguelike experience.

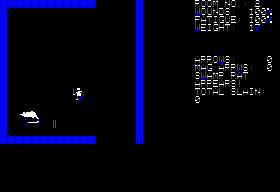

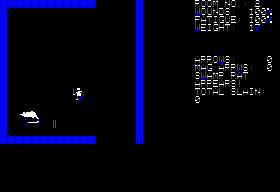

It doesn't surprise at all that Temple of Apshai hasn't got a lot going for it visually. The original TRS-80 version uses particularly abstract graphics, but even in the more advanced ports the dunjons look sparse and monotonous. In place of fancy graphics stand textual descriptions of the rooms, once again very akin to text adventures, as both find their roots in the choose-your-own-adventure type books of the 70's. These, however, are not displayed on screen. Disk space limitations forced the Automated Simulations guys to move all those to the manual, or "Book of Lore". In fact, it almost feels half like playing an adventure game book. It certainly doesn't represent what a 21st century mind is conditioned to expect from a video game, but for the nostalgist leafing through the pages in front of the screen is a reminder of times when commercially successful games could explore new possibilities that don't revolve around visual pomp.

Each room comes with an unique number, which can be looked up in the manual for a detailed description of the surroundings, which not only supports the imagination of dark, moldy caverns, but also gives valuable hints for exploration. A typical room desctription may read like this:

Room Fifty-six—is a passage with rough stone walls and floor and a native granite ceiling. The south wall of the passage is faced with smooth squarish stones near the far end, while the floor and other walls are of a rough stone. A foul, musty odor fills the air and a thin layer of moss coats the floor at the extreme end of the passage.

Keen adventurers know by now that they have to search for secret doors in the southern wall, and there might even be a minor treasure (incense moss) waiting in the next room on the far side of the passage. Treasures are equally number coded, although here the same number might be re-used several times. Most of the loot is sold upon return to the inn, only occasionally the search is rewarded with magical (or cursed) equipment.

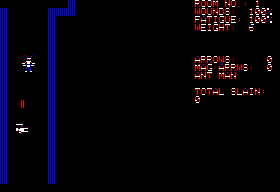

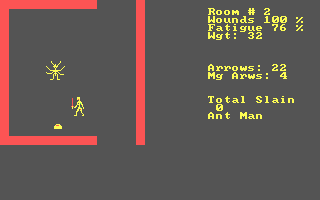

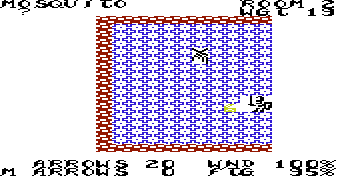

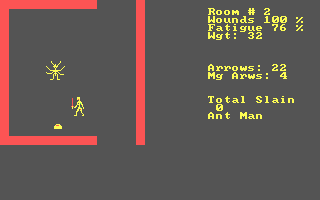

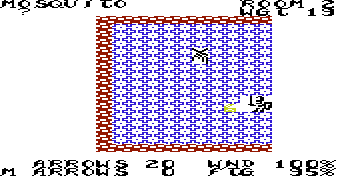

Temple of Apshai was first conceived and programmed for the Tandy-Radio-Shack-80 and Commodore PET, but almost immediately ported to Apple II computers as well. This version replaces the abstract pictographs of the original with character graphics that actually try to look like fantasy creatures. When facing north or south, the character is just tilted by 90 degrees, making it sometimes confusing as to which direction one has to turn around. Both early versions have a very slow screen composition phase for each entered room, requiring a lot of patience from the player.

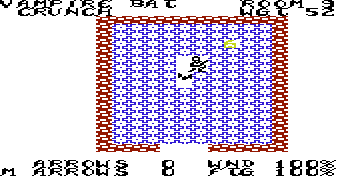

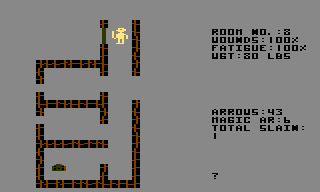

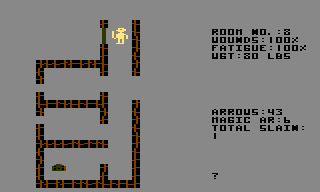

In 1982 followed a port for Atari 8-bit computers, programmed by Aric Wilmunder, who later co-developed the SCUMM scripting engine at Lucasfilm Games for Maniac Mansion. This added sound effects like footsteps or the jarring of doors to the formerly silent game. It was also much more pleasing to the eye, with a faster room drawing routine than the previous versions and used two different tile sets for the dunjons, a feature even the later Commodore versions lack. Those were released in 1983 and added basic music, mostly short jingles played after slaying a foe or grabbing a treasure. Most notable, however, is the eerie drumming beat that can be heard whenever a monster is on screen. The Atari version is nonetheless the most recommendable among the bunch. The dunjon layout by Jeffrey A. Johnson (Roadwar 2000) is the same in all versions, but enemy placement differs occasionally.

An odd place takes Temple of Apshai for Coleco Adam. This version was never officially released, but a beta version got leaked. In its screen composition it feels like a missing link between the original and Trilogy versions, but the disk only contains the 4 initial dunjon levels. The strangest part, however, are the controls. The numbers still set the current walking speed, but now the character is controlled directly, attacks are executed in real time. Monster speed is chosen between 9 levels instead of 3 and makes a huge difference in balance. Not all functions have been implemented in this version, though, and it appears rather glitchy.

From a present-day perspective Temple of Apshai certainly seems utterly outdated, old-fashioned and ugly at first glance. Yet at the core of the experience at least the technically more advanced ports (mostly Atari 400/800) hold up surprisingly well, despite the lack of now seemingly mandatory features like a spell system or random-generated levels. The dunjon crawling proves really fun and addictive, leaving one longing for more after clearing out all of the temple's four levels. Further difficulty options, some kind of enemy scaling and of course more dunjons would have been nice to keep experienced players (and characters) entertained, but this is were the numerous sequels and add-ons come into play.

|

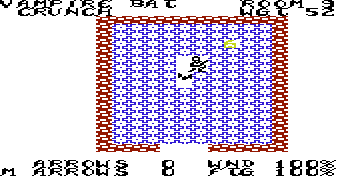

Temple of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Temple of Apshai (VIC-20)

|

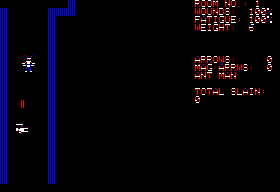

Temple of Apshai (Apple II)

|

Temple of Apshai (TRS-80)

|

Temple of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Artwork from the manual

|

Temple of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Temple of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Temple of Apshai (Commodore 64)

|

|

[Add-On] Upper Reaches of Apshai - TRS-80, Apple II, Atari 400/800, IBM-PC, Commodore 64 (1981)

|

Although the very first Dunjonquest was equipped with the ability to load alternative scenario disks from the get go, Freeman, Connelley and Co. didn't start to produce expansions until 1981, when most of the standalone entries in the series were already finished. Its status as an expansion is actually misleading, as it is balanced for newly created characters, while heroes that completed the four dunjons of the original will simply breeze through, that is unless they fall asleep in the process.

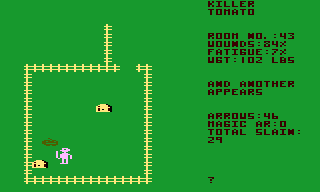

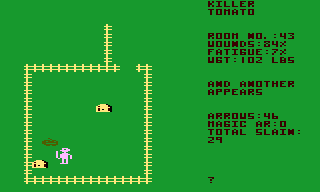

Upper Reaches is surprisingly whimsical after the mostly grim atmosphere of the first game and feels more like a spoof than a sequel, sending players to "explore" the town that lies above the temple ruins. Here the quests involve mostly chores and visits, in place of Antmen and Skeletons you fight angry housewives, rabid chickens and killer tomatoes.

There's no epic tale to explain this madness, the hero just goes on four unrelated quests that all involve the "NPCs" from the first game. First the innkeeper wants his backyard cleaned out of weeds, which makes for the most boring "dunjon" in the whole game. While in the original an array of rooms could share one single description, here half of the map is just one boring berry field. Next the protagonist visits Merlis the sorcerer, one of the three possible resquers in case of death. Apparently he owes us some money, that we intend to collect. This maze uses some interesting features, like rooms that open only up after a certain trigger, but it is very small in size. The third one, visiting the dwarf's castle and the woods surrounding it, is not much bigger. The only full-fledged quest is the last one, in which the priest Benedic leads players to a monastery where a vampire is running rampant. The problem with this one are a special breed of enemy, though, whose attacks have a "chilling" effect, which permanently reduces constitution. This is very frustrating, as it directly affects fatigue, and the game doesn't offer much opportunity to raise the base attributes.

All things considered, Upper Reaches of Apshai is an at best mediocre expansion to the core game. The inconventional quests that usually should make for a more interesting game only show too clearly the limitations of the old Dunjonquest engine (considering that by now Ultima is out). Despite the nominal tasks, all you do is still slaying monsters and collecting treasures, killing the innkeeper's wife has as little consequence as slaying Merlis' cats and messing up his experiments. Angry monks attack when going near their possessions despite the warning in the manual, but one might as well murder them all in their sleep without any noticeable repercussions. Eventually one begins to wonder what the point to all this might be, but yeah, it's just that the game demands a bit of actual role playing (or make-believe, if one prefers) on the player's part.

Version differences are exactly the same as before. No surprise, as the expansion requires the original program disk and only contains replacement data files for the dunjons. Only the version for Atari computers can now truly shine by displaying an unique tileset for each level.

Upper Reaches of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Upper Reaches of Apshai Atari 400/800 Cover

|

Upper Reaches of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

Upper Reaches of Apshai (Atari 400/800)

|

|

[Add-On] Curse of Ra - TRS-80, Apple II, Atari 400/800, IBM-PC, Commodore 64 (1982)

|

The second and last expansion to Temple of Apshai leads even further away from the eponymous temple, to ancient Egypt. Curse of Ra takes the series back where it belongs: Into dark ruins and crypts. Those come in form of all the stereotypical Egyptian settings, pyramids, the Sphynx (don't remember ever reading about it being hollow, but well...) and finally the Temple of Ra.

While at least a partial return to form, Curse of Ra's levels have several problems, too. Except for the first one, they have about as many rooms as the Temple of Apshai dunjons, but part of them lies actually on the outside. Now part of the quest is it to get into the structure itself, which rarely amounts to more than tedious walking along the walls and examining them until one finds the secret door in. The Egyptian ruins hold many traps and secret doors, but the actual "main" route through often proves rather linear. Room descriptions are equally a mixed bag, with some good ones, but also a lot of uninspired repetition. Ra's temple, while otherwise well designed, has a bad habit of trapping the player with "chilling" enemies, so you're lucky if you can still walk at all at the end. This effectively destroys the character for future exploits. With that rather unfair exception, the difficulty is once again low. The first dunjon starts with a recommendation for level 2 characters.

Curse of Ra (C64)

|

Curse of Ra Atari 400/800 Cover

|

|

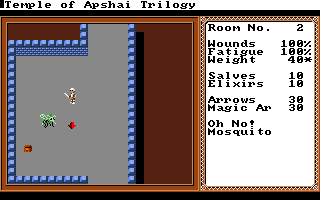

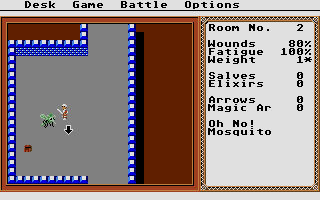

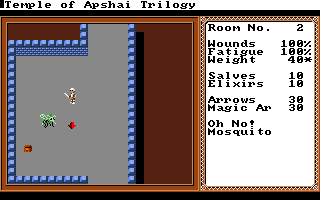

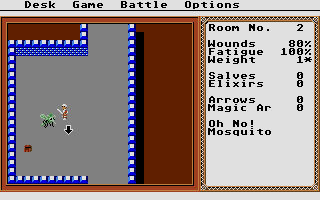

[Remake] Temple of Apshai Trilogy - Apple II, Atari 400/800, Commodore 64, IBM-PC, Mac, Amiga, Atari ST (1985)

C64 & Atari 400/800 Cover

|

Atari ST Cover

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Apple II)

|

|

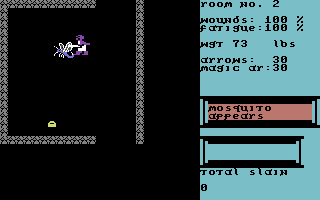

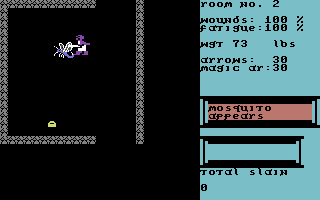

In 1985, the Dunjonquest series was long discontinued after the departure of both its founders. Epyx, however, then decided to remake the most successful game in the series, slapping on the two expansions to sell them as one package. This new release entirely drops the Dunjonquest brand name (the trademark was abandoned on February 29th, 1984). The title screen boldly states: "Redesign by Stephen Landrum" (Dragonstomper, Summer Games), but the way the game is played hasn't been changed much, wherefore the release must have felt like an antiquity in its time. The moniker "Trilogy" also feels abused, as the only true direct sequel to the original Temple of Apshai — Hellfire Warrior — is of course not included. Seeing how all the games are based on the same engine and how light on artistic ressources each of them are, a Dunjonquest Complete would have been much more appropriate to hone the series.

There are a few changes in the balancing, most notable with character fatigue, which drops much slower now and feels almost pointless. The game now also offers the luxury of calculating your treasure income for you, so no cheating at that part, anymore. It still allows entering character values to hearts content at the beginning of the game, though.

The graphics got completely reworked, of course. They all take advantage of the very different platforms they're released on, but are more coherent in style than the various ports of the original. All of them are inferior to the old Atari version when it comes to graphical variety in the dunjons, reusing the same tilesets much more often. With the exception of the Apple II, all new versions are also supplied with very catchy chiptune music themes for the title and loot overview screens. It's easy to find oneself keeping them looped for hours on end.

New systems supported are the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST and Apple Macintosh. Most notably the character is now maneuvered through the dunjon with a point & click interface. (The original control scheme is still functional, though.) It's also no longer necessary to look up room descriptions from the manual, as they can be accessed from an ingame menu. Back in the day the remake might not have been received too well, but for interested retro gamers that don't want to put up with the archaic original controls and graphics, those two versions are a godsend.

To go on an interesting tangent, the more modernized 16-bit computer ports were done by Westwood Associates, who with this title started their career that should encompass some of the most popular WRPGs of the early 90's before they became "the Command & Conquer company". Westwood founders Louis Castle and Brett Sperry apparently took the deal with them when they left their former employer ACT, as that company's owner Peter Filiberty lists an Apple Macintosh port of the Trilogy in his résumé. The Macintosh version was also completed by Westwood, but it is extremely rare, as are screenshots for this monochrome variant of the game.

Louis Castle said about Westwood's Apshai-conversions in an interview with Computer And Video Games:

One of the very first games we did as Westwood was a port of a game called The Temple of Apshai Trilogy, and the reason I bring that up is because we implemented realtime gameplay into it. Our publisher told us that it was just too difficult for people to understand, and that we had to go back to making it a turn-based strategy game like the original was. So from the beginning we were always looking to make games that had that sort of time pressure in addition to making you think. It's not enough to make people have to act quickly, but they have to think quickly as well.

Quite a curious bit of information. Should Westwood—or ACT—be connected to the mysterious Adam prototype? Or was the failure of that port the basis on which Epyx denied Westwood their longing for real-time gameplay?

MP3 Download

Temple of Apshai Trilogy Title Theme (C64)

Manual Artwork

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Amiga)

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Amiga)

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Amiga)

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Amiga)

|

Temple of Apshai Trilogy (Amiga)

|

|

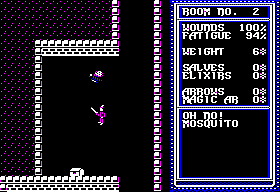

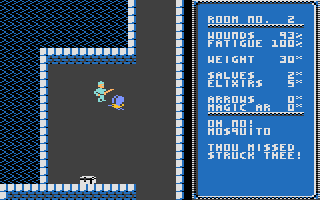

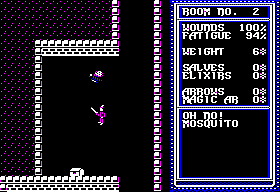

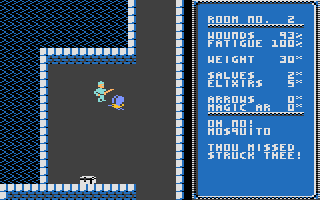

Comparison Screenshots - Dunjonquest: Temple of Apshai

TRS-80

|

Commodore PET

|

Apple II

|

Atari 400/800

|

IBM-PC

|

Commodore VIC-20

|

Commodore 64

|

Coleco Adam

|

Comparison Screenshots - Temple of Apshai Trilogy

Apple II

|

Atari 400/800

|

Commodore 64

|

IBM-PC

|

Commodore Amiga

|

Atari ST

|

Apple Macintosh

|

Datestones of Ryn - TRS-80, Commodore PET, Apple II, Atari 400/800 (1979)

Cover

|

Manual

|

Datestones of Ryn (Atari 400/800)

|

|

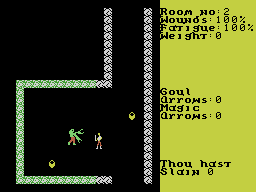

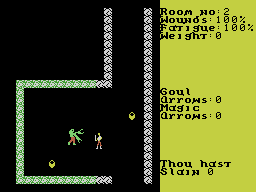

Chronologically the second game in the series, Datestones of Ryn functions as kind of a prequel to Temple to Apshai, as it shows an episode in the life of Brian Hammerhand as a young soldier, whereas he was depicted as a bedraggled veteran before. His unit has hunted down a band of thieves, who have stolen the valuable Datestones necessary for the calender of Ryn, up to the entrance of a cave. The lieutenant fears an ambush for his men in the dark, so he sends the lowest ranking soldier alone into the cave.

This time Hammerhand is the only available character, there is no generation process in the game. The bandits have a secret getaway route inside the caves, thus their their impending escape by nightbreak has to be prevented. This limits Hammerhand's quest to 20 minutes and makes the theme for this episode, Automated Simulations' first MicroQuest. Sold at half the price of a regular game, this time there's only one dunjon to explore, which is also significantly smaller than each of the four in the first game.

What initially sounds like a rip-off are Automated Simulations' first awkward steps toward a pairing of RPGs with arcade games, that would eventually culminate in the advent of the action RPG genre: The game is conceived for competetive highscore hunting. The manual even recommends the game for tournament play, in fact the company already held a preview tournament prior to the game's release at the 1979 Pacificon.

Inexcusable, however, seems the loss of room descriptions. When Epyx wanted to go and create an all-out arcadey feel, they might as well have used random dunjons, or at least included a map editor. Coming from board- and war games, Jon Freeman of all people should have known about the power of customization and randomization. But maybe this was one of the things he couldn't convince Connelley to be feasible in a computer game, a cause of grief for Freeman on more than one occasion. In an Interview on Crush, Crumble & Chomp! he remembered:

I had done some design work in the late '60s for a war game featuring movie monsters, and I had proposed doing such a game at Automated Simulations first in late 1980 and again in early 1981, but my partner in ASI, Jim Connelley, didn't think it could work. The third time I suggested it was shortly after the publication of the board game, The Creature that Ate Sheboygan, which convinced him that such a concept was both plausible and appealing. (Interview conducted by Cybergoth at The Epyx Shrine)

Players start out with fixed stats and equipment which they have to use to their best ability to recover the Datestones, which are the most important criterion of scoring, but only if brought back to the exit of the cave in time. Slain brigands and beasts immediately bring extra points, but only the bandit leader's head can outweigh a stone. It is important to weigh carefully between securing the stones at the exit and protruding deeper into the cave, as the time limit usually won't allow two full-on raids. If the time runs out before Hammerhands return to the exit, the Datestones he is currently carrying are forfeit.

While a respectable attempt towards new frontiers, Datestones of Ryn appears as a not fully thought out concept. The game runs on the mostly unchanged Dunjonquest engine of the predecessor, whose reliance on stats and ressource management loses most of its meaning when those parameters are fixed from the beginning. The appeal of time management in turn doesn't come to its full potential because of the combat engine's rather high random factor. The time limit is also set so tightly that the question when to return to the exit is really only raised once per game.

Once again the initial platforms were TRS-80 and Commodore PET, with an Apple version following soon, bundled with Morloc's Tower and Starquest: Rescue at Rigel. The differences among these versions is the same as Temple of Apshai. Interesting proves the Atari port, which is inferior compared to the first game. The graphics are less refined, like on Apple computers the protagonist sprite is merely rotated for vertical directions. This divergence is caused by the fact that Datestones of Ryn was in fact released on Atari computers earlier than Apshai. Together with Rescue at Rigel and Invasion Orion, it was among the first games Automated Simulations ported to the system.

There is also a Commodore 64 disk image floating around the net, but it is very likely that it was inofficially converted from the PET, as it is completely identical save for the font and standard colors. Apart from this probable bootleg, Datestones of Ryn marks the begin of a slow decline in ports. Not only a proper C64 port is missing, but also the VIC-20 and IBM-PC platforms are neglected. Given that those conversions were among the latest for Temple of Apshai, this may have to do with Epyx discontinuing the series.

|

Datestones of Ryn (Atari 400/800)

|

Datestones of Ryn (Atari 400/800)

|

Datestones of Ryn (Atari 400/800)

|

Datestones of Ryn (Atari 400/800)

|

|

Comparison Screenshots - Datestones of Ryn

TRS-80

|

Atari 400/800

|

Commodore 64

|

Page 1:

Intro

Temple of Apshai Trilogy

The Datestones of Ryn

|

Page 2:

Morloc's Tower

Hellfire Warrior Trilogy

Sorcerer of Siva

|

Page 3:

StarQuest Series

Crush, Crumble & Chomp!

Gateway to Apshai

|

|

Back to the Index

|

|