Seeing the first Mother game’s commercial success, it was only a matter of time before Nintendo asked for more. And this wouldn’t take long indeed – the second episode’s development started as soon as 1990. Pax Softnica wasn’t involved in the project anymore but the APE studio, who retained all of its talents, wasn’t all alone on this since none other than the aspiring HAL Laboratory joined the dance. The new possibilities offered by Nintendo’s 16-bit hardware was warmly welcomed by the developers who experienced a creative freedom absolutely unheard of back when they were burdened by the Famicom’s limited technical capabilities. It seemed like a pretty good start. Well, it SEEMED. The programmers actually started encountering a lot of problems pretty quickly- the angled perspective didn’t prove as easy to manage as it was on the first game, and some new game mechanics such as the delivery system were very hard to deal with. On top of that, the intended 8Mb capacity proved itself to be barely sufficient to store even the game’s music. The fact that the two studios that worked on the game were based in different areas of Japan didn’t help. Actually, EarthBound was getting in a pretty deep mess. Deep enough to go as far as to call it development hell.

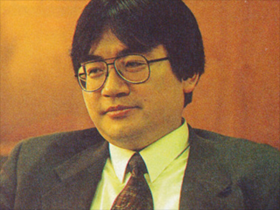

Then some kind of messiah was sent by HAL to rework a lot of stuff from scratches and said person, after assuming the role of lead programmer, managed to deal with the game’s programming issues and wrap it all up. This skilled programmer’s name was Satoru Iwata. That’s right, the person who would become the head of the Nintendo company around ten years later is the very same person who saved EarthBound from demise. In the end, the project ended up getting even larger than initially intended: The required memory to store the game tripled to reach 24Mb, and development ended up lasting more than four years. Even by today’s standards, this is a pretty serious time span for game development, so just try to imagine what that could mean almost twenty years ago. This unexpected project upgrade had its advantages from a creative standpoint, though – Itoi wrote a huge amount of dialogue, sometimes spelling them kana by kana to the typer, and the returning composers wrote an equally impressive number of tracks who make up for one the Super Famicom’s most astonishing soundtrack.

Satoru Iwata (lead programmer), Hirokazu Tanaka (composer) and Kouichi Ohyama (art director).The year is 199X. The setting is Onett, a small town in Eagleland. The night has fallen. We approach a house in the northern part of village – it’s the home of Ness, a somewhat ordinary 13-years old boy who is sleeping soundly at the moment. Suddenly, a very loud noise comes crashing through the night from the top of the neighboring hill, and the sound of police sirens soon follow. Thrown out of his bed, Ness can’t help but feel like catching a glimpse of what just happened. And strangely enough, it seems like a meteorite has fallen atop the town, but it’s impossible to get any closer, as the police force has restricted the access to the area. As Ness returns back home, his annoying neighbor comes whining for Ness to accompany him to the crash zone. Once there, what they see is absolutely beyond belief – from the inert celestial body bursts out a light ray, revealing a talking rhino beetle from the future that calls itself Buzz Buzz. His purpose here is to warn Ness of a great danger – in the future, Giygas, the “cosmic destroyer”, has devastated the Earth and everything is desolation. But this tragedy can still be averted, as the Apple of Wisdom has foretold that four Chosen Ones would prevent the disaster. And Ness so happens to be one of them. A fateful night indeed.

Ness – ネス

The hero from Onett. Again, it’s your baseball-loving American boy with PSI powers – Itoi stated that whether or not this character is supposed to be the same person as Ninten was left to the player.

Paula – ポーラ

The daughter of the Polestar family of teachers from Twoson. A cute girl but also a powerful psychic, she manages to contact Ness through telepathy just before being kidnapped by the Happy Happyist cult.

Jeff – ジェフ

The new nerd, from a private school in Winters. When Paula prays for his help through telepathy, he crosses the world and saves the day for the team using technology developed by his father, Dr. Andonuts.

This is the strange premise on which EarthBound starts up. The introduction is, at the very least, consistent with its predecessor’s quirkiness, and it’s only going to get crazier. But what about the gameplay, the balance and all that stuff? Is this still a Dragon Quest clone?

EarthBound remains a rather classical JRPG in substance, in the same vein as his predecessor, and its main quest is still about traveling the world to gather eight melodies. However, even though it may sound similar, a lot of stuff has hopefully been updated for this new episode. First of all, the progression isn’t hazy like before. The first game’s huge continuous map has been revamped more linear network of roads (not dissimilar to what would become a staple of the Pokémonseries) which allows for a better structure and richer environments.

This is followed by another serious change in gameplay – say goodbye to random battles, as now enemies are directly visible on the map. Naturally, they will chase after you the moment they discover your presence, and you should be on your guard. If an enemy surprises you by attacking your back, he’ll get the first strike. The opposite is true as well, though – if you manage to approach from enemy’s back, you’ll get the advantage. This gets even more interesting knowing that once you reach a certain level, mobs who aren’t powerful enough to face you anymore will promptly flee. You can chase these cowards down in order to deal a fatal blow – the screen will flash to notify an instant win without even going through the battle screen. Handy!

Speaking of battles, they are far better balanced than they were in the first episode. Not only do they seem fairer, but the most merciless blows you’ll be hit with are now actually confrontable thanks to a brand new mechanic – the rolling HP meter. When you suffer from an attack, the damage you’re dealt isn’t simply subtracted from your total of health points – it rather gradually rolls down in a fashion somewhat similar to that of the digits on an old gas pump. While your HP is dropping down, nothing stops you from using an healing item or PK power for an emergency regeneration, or even to try to deal a last resort blow to your enemy in the hope to knock it out and put an end to the battle before the bell tolls. The meter spins pretty quickly and it may seem a bit hard to apprehend at first, but you’ll soon get used to it. A new stat called “guts” is also introduced, which not only determines the chance of dealing a critical hit but also that of surviving a mortal blow. Even the most ferocious opponents are now put into perspective thanks to that new way of managing damage, and what may seem like a frivolous addition at first will save your life more often than you may expect. That added “dynamic” mechanic is a much welcomed plus to make the battles more lively.

It’s true EarthBound‘s gameplay isn’t perfect, though, and it feels somewhat stiff here and there. The inventory is still a hassle to deal with, and a button for running wouldn’t have been a bad idea either especially since it was sort of implemented in the first episode’s US prototype. The very beginning of the game may also seem a bit tough but it’s nowhere as crazy as the first episode, and this initial difficulty will not last for long. These minor flaws are mostly details, and they won’t get in your way too much, contrary to how the first Mother‘s faults could sometimes ruin the whole thing. EarthBound is actually fun to play, and it’s all thanks to that core game design and balance update. Now that the gameplay has improved, the strange atmosphere is more easily enjoyable.

The first entry in the series was already pretty wacky, unique and packed with subtleties that set it apart from the other RPGs of the time. By using a setting similar to that of its predecessor, wouldn’t Itoi be incurring the risk of repeating himself? Well, actually, no. Not at all. When compared to its successor, the first Mother game actually looks like a prototype, in which the huge brain-frying device that EarthBound symbolizes was only starting to form. The setting is indeed similar, but it’s greatly expanded thanks to the Super Nintendo’s new capabilities. The first tour-de-force are its visuals: the game uses a very colorful blending of minimalist sprite art and cartoonish character designs that puts a plethora of environments and NPCs to life in the most fascinating way possible. But this graphical update couldn’t have been complete without a reworking of the battle screen, which was indeed very stark in the first episode. Not only have the enemy sprites received the same care as overworld sprites, but battles are now set to the motion of a mind-boggling variety of procedurally-generated abstract animated backgrounds that create a highly psychedelic ambiance that couldn’t fit the game better.

The bestiary extends to more than 150 truly bizarre creatures, including a comeback by the famed hippies and the iconic Starmen, but it now sees the arrival of rowdy mice, mobile mushrooms, stinky ghosts, spinning robots and a whole bunch of other multiform UFOs – in short, it’s an incredible melting pot of comical beings, possessed animals and crazy machines. This weird pack of fiends act as strangely as they did in the first game – while the old-party men that assault you in the streets of Twoson may manage to take your guts down by rambling about today’s youth, delinquent ducks are way too stupid to actually attack without almost constantly falling over. Not to mention bats’ and protoplasms’ depressive tendencies, their attempt to understand what’s happening around them inevitably ending up in self-induced confusion. Battles in EarthBound aren’t just a process through which you go to make your way around the map or gain experience: they’re a real delight in themselves, and you’ll probably find yourself assaulting every new enemy you stumble across out of sheer curiosity. The battle system may not be revolutionary, but the attitude certainly is.

That’s how superior hardware can be used to create a better game. And the Super Nintendo not only allowed for a better-looking world, but also for the inclusion of an endless amount of detail, as the veil from its predecessor’s scenario has been lifted, revealing an incredibly polished universe. The variety in NPCs is simply something never seen before: from the fat middle-aged housewives to the weird kids with hockey masks, not to mention punks, rastafarians, and Mr. T, and of course the incredible Mr. Saturns (beings of an alien race that

The paradoxical consistency of this crazy world is backed by a remarkable drive to polish every aspect, and you can feel how much passion went into the game. Now, you have to buy your healing food at the local junk food joint, and you can even put sauce on it. Or, you can even browse the nearby trash cans for some leftovers (yuck). Maybe you’d rather order a pizza by phone. Beware, though – while you’re walking around town waiting for your pizza pie, know that there are possessed NPCs wandering around those supposedly quiet streets out to smash your head in. These unexpectedly dangerous urban areas are all served by bus, so you’ll get the chance to make your way around easily for the price of a ticket. This would also be the perfect occasion to come back home from time to time to see your family, because Ness is still a kid after all, and he’ll miss his mom during his world-saving journey. You’ll have to at least occasionally phone your mom to make sure our young hero doesn’t get homesick and start to feel depressed in the middle of a battle. This makes EarthBound all the more convincing, and this couldn’t have been a better context for one of the game’s staple – its humor.

The absurd rendition of Western culture carried out by EarthBound let nothing escape its grasp, parodying with the same unsettling light-hearted tone nostalgic teen fads and corrupted cops or suburban architecture and the Ku Klux Klan. A special mention goes to the pervasive sci-fi B-movie raygun gothic imagery, which starts up at the very intro screen. Even the caricatural pristine lawns are straight from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. The player really gets the feeling he’s thrown in a world where the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s have fused during a space-time breach, like they are experiencing an alternate reality that wasn’t actually so different from our own. The events that occur in this surreal world swings from tribute to satire, and this erratic tone makes EarthBound‘s drift into something that just didn’t exist before. Direct pop culture references are numerous – you’ll have to go through a valley named after a rock group, while the blues concerts of the black-suited Tonzura Bros. are going full swing in a world where basically everything oozes of the cultural legacy of the Beatles… maybe even down to your party members actually, if you choose to name them using the randomized “Don’t care” option!

This universe couldn’t have been a better context for EarthBound‘s dialogues to shine. The case for this game’s dialogues is a bit special actually, as one of its main characteristics was kind of lost in translation – it being written only in kana (syllabic), at a time when, due to the increased memory of 16-bit consoles, the developers were finally able to use kanji (logograhic) as in all types of writing outside of video games. Itoi’s decision wasn’t just arbitrary, of course – kana-only texts have a peculiar coloration, due to their easy free-flowing reading and the childlike, low-level skills required to understand them. What was an 8-bit era limitation turned into a new form of game poetry. To try to get that feeling in the localization must have been a tedious job, and the best way to keep the feeling as most authentic as possible was to give these dialogues a “fleeting”, nonchalant, casual feel. And apart from a few hurdles, it’s a stunning success, especially for a 1994 localization. That’s a relief, as the thousands of intentionally loose-cannon dialogue lines are an integral part of the game’s almost ungraspable style.

But that’s only one side of the game’s dialogues, and their most lasting impact obviously lies in the oddball fun it induces. That whimsical, offbeat humor will make you laugh in a way not dissimilar to that of Monty Python’s Flying Circus – witty lines, quirky meta-jokes, meaningless chat-chat, blatant nonsense and ludicrous philosophizing are what make up most of the game’s otherwordly script. Everything but something useful to the player, actually. The NPCs walking around the world of EarthBound give the curious impression to live a life on their own rather than being there to “serve a purpose”, whether it be giving clear indications to the player or defining a town’s tone. Sometimes, it even feels like these NPCs are trying to speak directly to you as a player, without using your in-game intermediary. There is a pervading feeling throughout the whole of the adventure – the game is aware that there is someone in front of the screen holding the pad in his hands. That probably is the most stunning aspect of EarthBound‘s parodic instinct – its willingness to almost constantly play around with RPG tropes. The first Mother game sometimes felt like it was making fun of our medieval fantasy-influenced expectations, but with EarthBound, it’s not just making fun, it’s deliberately trying to mess with you at every opportunity.

“The adults in EarthBound tell lies. Telling a lie in a game means that the functionality of direction leading a player through the game becomes increasingly unreliable. But realistically speaking, we’re surrounded every day of our lives by people who aren’t entirely honest or straightforward. That means it would only make sense for someone like that to show up in a game – I see it as a given…The game’s lines were like haikus. Even haikus have that “so what?” kind of feeling, but that’s the part where the player jumps in. Mother had quite a few of those lines that kind of cut you down and triggered your imagination by making you go: “Wait, what? What the hell does that mean?”…I didn’t want to make a game whose characters and towns were simplified by symbols.” – Shigesato Itoi

And when it comes to putting the game design elements that rhythm the progression of an RPG into motion, it’s not taken with a pinch of salt – why pretend “tips” are read from a crystal ball when they really are just known by the NPCs that built a business around their dispensation? Why stage grandiose events to justify your inability to progress further when you can let the roadblock-obsessed police bar you access to the next town? Why not just tauntingly throw a nonsensical statue in your path? “Normally you’ll just block a path with a rock, you know?” as Itoi plainly stated. Even in-game characters sometimes theorize about their own world, like Brick Road: “Once a dungeon is built, monsters always start moving in.” EarthBound‘s events aren’t just funny, absurd and full of references, they also go to great lengths to assert their nature as kind of self-conscious game mechanics rather than as scenaristic excuses. It’s not just witty, it’s truly an alternate reality which expresses through these strange occurrences. EarthBound has a real mind of its own. This screen-smashing iconoclasm will lead you to the most odd premises, and expect to get tricked by this metaphysical intelligence – it will not refrain from having you spend money on absolutely useless investments, among other stunts. In fact, many things in this game are useless. In EarthBound, the useless take on a new meaning, and what used to look futile suddenly emits a strangely inviting aura. Kind of a paradigm shift from calculating RPG gaming. EarthBound can’t break the fourth wall, for the very reason that it never built any in the first place. Are you playing EarthBound, or is EarthBound playing you?

“Being weird or goofy isn’t my only aim. It might not be something game creators these days go for, but more than anything I have this strong desire to make people feel distraught. I want to give them laughter and joy too, of course, but I’ve always filled with the desire to make people feel ever-so slightly heartbroken.” – Shigesato Itoi

In the end, EarthBound is the ultimate post-modern experience. “Post-modernism” is a bit of an overused expression, so let’s definite it clearly right here – let’s say it’s a critical way of seeing things that tends to consider there are no objective truths, that what are supposedly self-evident concepts are often nothing more than social constructs, and that everything should be questioned and deconstructed as a result. Of course, post-modernism is riddled with purposefully unintelligible gibberish, but EarthBound doesn’t stand there – it’s in complete opposite of that vanity. This game is unique in a lot of ways, but its most stunning achievement probably is its capacity to parody what was taken as granted in its own medium, even though it’s also the fullest incarnation of it at the same time. EarthBound is always witty, but never pretentious; always packed with pop references, but never plagued by name-dropping; always thought-provoking, but never pompous; always transgressive, but never patronizing. If the soul of a homeless beat-generation existentialist street artist could fit in 24Mb of space, it would be stored on this Super Nintendo cartridge. This game’s ability to make philosophy and popular culture cohabilitate without ever actually making a clear distinction between the two clearly is one of its most defining aspects, especially when you know its target audience wasn’t the hardcore gaming niche at all but openly “grown-ups, children and even young women”, according to Itoi.

As we’ve just seen, EarthBound has a whole world, and a whole philosophy to explore, and the music fits its setting like the first Mother‘s 8-bit rock’n’roll songs did. It’s funny – the series’ soundtrack evolution can be compared to that of the legendary Brit pop band of which everyone at the APE studio is a fanboy, Itoi first: The Beatles. They have defined a whole era with their early rock songs, but the most interesting tracks of their discography probably are their later pieces, which are more experimental in nature. The same thing happened with Mother, only amplified by several orders of magnitude – while Mother had a distinctive pop-rock sound that fit its setting perfectly and set it apart from other RPGs, EarthBound goes WAY further. Its soundtrack is not only one of the most eclectic and experimental soundtrack in the history of video game, it’s also one of the best ever produced, pure and simple. The main reason behind this is the fact that, this time, Hirokazu “Hip” Tanaka is the one who lead the direction of the game’s music. Suzuki’s work is at its zenith as well and his melancholic folk- and chamber-influenced pop melodies are absolutely mesmerizing, but what is the true force behind EarthBound‘s music is Hip’s love for textural, minimalist electronic music and lack of interest in traditional musical structure. And the result is simply out of this world.

The game opens on a mixing of weird sounds, shouting and roaring guitars that sound like noise rock; the character naming screen features an intriguing synthpop-styled track; the first steps Ness makes outside of his home are accompanied by a blending of haunting synth and atonal drums; the first pieces of battle music already display minimal techno and electronica influences; and the first session of dungeon crawling is carried out in the midst of dark ambient echoes. And that’s only the beginning of the extraordinary sound travel you’ll get to experience. One of the most remarkable aspects of this soundtrack is the work on the bass, which is not surprising knowing of Hip’s love for dub music. The game incorporates influence from a variety of other genres, such as free jazz’s syncopations, musique concrete’s real sound mixing or shoegaze’s walls of sound.

And not only is it that good, it’s also very prolific – there are no less than TEN themes for the battles alone. In the end, the music of EarthBound is indeed a real “monster”, as the sound team stated in that interview on their musical influences. Sticking to the game’s pop culture patchwork aesthetics, they went as far as to experiment with something barely ever heard of in video game music: Sampling, even though it was legally risky. However, rather than use samples as the main rhythm like they are generally handled in house or hip-hop, Tanaka’s are like hidden in the tracks’ frequencies, adding an almost subliminal quality to the end result. Some tracks go as far as to be composed of nothing more than a manipulated sample, and that was before “plunderphonics” had even made its way into the mainstream. EarthBound is probably the first video game soundtrack to use samples, or at least the very first to use sampling in such a daring way. EarthBound‘s music is of absolutely mind-boggling quality in spite of the obvious artistic risks that were taken in its production.

“I saw the overlong development time, in a creative way, as a good thing, because you have a lot of time to experiment with things. There are still a lot of Mother fans, people who are fans of the series to this day, and that’s probably because we had a lot of time to experiment with things and make something really creative.” – Hirokazu Tanaka

EarthBound is like a 30-hours long surrealist poem set to the sound of an avant-garde pop concert… except you can play it. It’s without possible comparison, and it would be a pity to miss what probably is one the most unique games ever created. The gaming experience you’ll get out of it may leave you fascinated for the renaming of your life – it’s just that awesome.

When it came time to localize the game into English, Nintendo of America’s legal advisers almost had an heart attack at the sight of this cultural mess. So, they edited out these quirks by the dozens, as not to upset copyright holders and moral guardians alike. Not only were any kind of references to alcohol, sexuality, death or religion an obvious no-no for NoA, but they chased down every little detail. Most references in the text to such things as Star Wars or even The Beatles were removed. Trucks that looked suspiciously similar to Coca-Cola trucks were changed to be less infringing. References to other Nintendo characters (or development staff members) were removed from the default name options in the name entry menu. The Blues Brothers-like band was denied its iconic clothing and renamed “The Runaway Five”, the Ku Klux Klan-ish Happy Happyists got their hood ridiculously altered. Bars are now cafes, but they went after the drugstores because they had “drug” in their name, and removed the red crosses on the hospitals due to trademark concerns with the actual Red Cross. Numerous enemy and location names have changed – “Gyiyg” is now a more pronounceable “Giygas”, the town of “Threek” is now “Threed”, the “Grateful Dead Valley” is now the “Peaceful Rest Valley”, and many, many others. There’s one section where Ness visits a mystical land named Magicant – in the Japanese version, he’s naked, but he’s given pajamas in the English verison.

Assorted historical or Japanese pop culture references were also removed or changed. However, the localizers did their best to adapt the material. The most noteworthy case are with the octopus (“tako”) statues and wooden doll (“kokeshi”) statues, which were removed with a “tako-keshi machine” (octopus eraser) and “kokeshi-keshi machine” (wooden dool eraser). In order to keep the goofy-sounding items, these were changed to pencil statues and eraser statues, removed with a “pencil eraser machine” and an “eraser eraser machine”.

An example of sprite edit due to cultural issues. A very thorough guide about changes made during the localization process can be read on Earthbound Central. This patch now actually restore the quasi-entirety of those original subtleties.

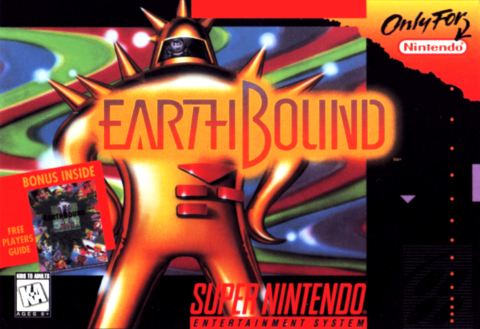

EarthBound was released on August 17, 1994, exactly five years and one month after the first episode. The release benefited from a pretty strong marketing campaign, including TV ads starring a friend of Itoi’s called Takuya Kimura who so happens to be one of Japan’s most popular pop idols. Of course, EarthBound was a success as hundreds of thousands of copies were sold within the first weeks, and gamers who were thrilled by the prospect of playing the sequel to Mother were absolutely compelled. It basically left a permanent mark in the history of Nintendo, the Super Famicom and video game as a whole; Itoi’s success was at its zenith. It was successful enough for Nintendo to decide it wouldn’t repeat the same error it did with the first episode. The English localization was completed in less than a year later. And for what would be renamed EarthBound for overseas release, Nintendo chose not to skimp on the marketing in this region either. Glorified by the now infamous slogan This game stinks!, the game was sold in an oversized box containing a game guide and scratch’n’sniff cards. It was definitely very ’90s marketing. Maybe too much, actually.

Sadly, it fell short. EarthBound sold barely more than 150,000 copies in spite of the “effort” that went into that humongous ad campaign, which is estimated to have cost around $2 million. Most video game magazines basically ignored the game, and the few that actually bothered to “review” it lambasted it for not looking like Final Fantasy or for having childish graphics. Retrospectively, this failure isn’t all that of a surprise. The game aimed to break from usual RPGs from the start, and that may have been ahead of its time in a region where even traditional JRPGs would not really enter the mainstream until the release of Final Fantasy VII in 1997. The rather dubious marketing didn’t really help either, especially since that “stinky game” was more expensive than the standard price. Of course, American adults were not interested in the game at all, contrary to Japanese adults who still played Mother even though the “casual boom” of the Famicom had weakened by then.

Nintendo drew a conclusion from this disaster: Never again! A bitter failure that would only be compensated by the cult following EarthBound would later gather when a combination of democratized emulation and Super Smash Bros. fame allowed for it to finally become popular, especially in Europe where it was virtually unheard of. The game’s relative though often exaggerated rarity and its late raise in popularity made its exchange value go through the roof at one point, now with a complete mint condition of the game weighing in the thousands of dollars and loose cartridges selling for more than $200. Thankfully, the game finally made an appearance on the Wii U Virtual Console, as well as on the SNES Classic console, so at least it is widely legally accessible for English speaking fans. In the end, EarthBound is a legend: It is widely (and rightly) considered as one of the best games ever produced by Nintendo in Japan. That the Kyoto giant knew well, and is wasn’t before long that a third episode was, hum… well, that’s a pretty long story.

In the 2003 release Mother 1 + 2 for the Game Boy Advance, the changes to Mother 2 are minimal. The screen view is smaller, and the music suffers from some fuzziness, but otherwise it’s mostly the same.

Screenshot Comparisons