At the turn of the 21st Century, the Real Time Strategy genre was reaching its peak in popularity. It had already seen the rise of several classic titles, including Command and Conquer, Starcraft and the historical Age of Empires series. It’s into this environment that Rick Goodman, one of co-founders of Ensemble Studios (and later founder of Stainless Steel Studios in 1997), sought to create an epic-scale RTS unlike what had been seen before. In a December 2010 interview by IGN with both him and writer-designer Stefan Arnold, the goal from the start was to combine the best of RTS gameplay (like Goodman helped innovate with in Age of Empires) with that of empire-building (reminiscent of Civilization and city-builders like the Caesar games). Encompassing historical, modern and even futuristic elements, the resulting concoction would be relatively novel compared to its competition.

The result is Empire Earth, released by Sierra Entertainment (as Sierra On-Line) for PC on November 13, 2001. The game didn’t quite live up to its lofty ambitions and was very much a product of its time, soon to be overshadowed by other titles. Nonetheless, it’s not for nothing that it, like the franchise it launched, was seen as a serious contender. And that even now, it remains an alluring piece of work.

At a glance, the gameplay would be familiar to anyone who’s played Age of Empires or its successors. You have “Citizen” worker units (recruited from Town Centers or Capitols) that are used to gather resources and build structures. Military troops can be trained from prequisite buildings (such as barracks and stables), provided there are enough funds. There is also a “rock-paper-scissors” mechanic at play, as well as “Hero” units (In the form of “Warrior” and “Strategist” type pairs) that can help turn the tide of battle. And on top of having provisions for a “wonder” victory – the wonder themselves come with their own bonuses, such as the Library of Alexandria allowing you spot enemy structures across the map – you can even “age-up” to unlock more powerful unit types and upgrades. Coupled with flexible skirmish/multiplayer options and a scenario editor, it can almost feel like deja vu. The devil, however, is in the details. Specifically, how Empire Earth takes all of the above and tries to go further.

One of the very first things you’d notice is how there are 14 “Epochs” as opposed to the relative handful usually expected in an historical title. This alone could arguably be said to be one of Empire Earth’s biggest selling points. Beginning with the Prehistoric Age (complete with cavemen and primitive grunting), a full-length match can cover 500,000 years of human history and beyond in a single sitting. But rather than just having the building styles or the UI design update accordingly, the transition from one Epoch (or general Epoch group) to another is more pronounced. The voices and attire of your Citizens, for instance, visibly change over time (eventually looking like white-collar workers with crisp American accents), while each successive unit upgrade makes them progressively more powerful; get left behind, and you’ll find out why even swarms of spearmen are hard pressed to defeat a handful of Imperial Age infantry. In addition, the game notably goes an extra mile by depicting the future (culminating in the Nano Age of the 2200s); whether it’s the sleek sci-fi aesthetics and laser tanks or Cyber mechs at your disposal – eventually, you’d be able to viably field whole armies of them, from anti-infantry Pandoras to the Prophet-esque Hades – this was something that few historical games really did outside of turn-based fare like Civilization: Call to Power. While such a vast scale and seemingly disparate styles would risk making the overall experience feel a bit disjointed – certain eras could easily feel like jumping through different genres altogether – the end result remains consistent and fluid enough that it’s not overwhelming.

Then, there are the smaller touches that make Empire Earth stand out, which highlight the empire-building elements. For instance, in place of simple drop-off points like in Age of Empires, Citizens build Settlements, which can be “populated” permanently by five units to become Town Centers, which provide additional productivity bonuses and morale boosts, as well as the ability to train more workers and hero units; “populating” 10 more Citizens, meanwhile turns those structures into Capitols, which have even more bonuses (such as economic technologies). Temples, meanwhile, not only train Priests that can convert enemies to your side and powerful if expensive Prophets (support units that cast “Calamities” like earthquakes), but also provide protection from said powers to anything within its radius. Then there’s the mechanic of upgrading individual attributes of units (such as attack strength or armor), which can be carried over to subsequent successors down the line and opens up new options on how to specialize them; according to Goodman and Arnold in the same IGN interview, this is meant to simulate “incremental technological and practical changes.”

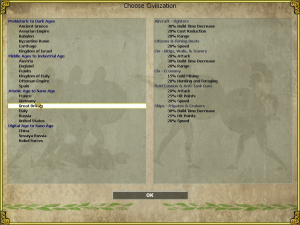

This isn’t to ignore the game’s other noteworthy aspect. While Empire Earth comes with pre-made factions (from Ancient Egypt to futuristic China), it also features a unique “Civilization Builder.” With a maximum of 100 “Civ Points” available in most skirmish and multiplayer bouts, you could spend those points on myriad bonuses; these can range from specific unit perks (like a 20% attack boost for bomber aircraft) that take up only a handful of points to more powerful enhancements (such as 20% cost reduction for Citizens) that are comparatively expensive to purchase. Although some of these bonuses work better for certain playstyles or Epochs than others – playing as the Byzantine Empire or having a cavalry-heavy build during the futuristic Digital Age wouldn’t necessarily be all that useful – the variety of options presented (along with being able to save your custom factions) provide ample room for versatility without being too overwhelmed. As this applies as well to enemies, whether it’s AI or other players, it also means that each subsequent bout wouldn’t be the same.

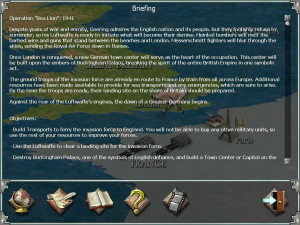

Empire Earth’s campaign mode is no less ambitious, though it’s here that the shortcomings start rearing themselves. Comprised of 37 scenarios overall, there are four campaigns available – covering the Greeks, English, Germans and Russians – set in distinct time periods; this isn’t including the “Learning” tutorial, which chronicles the rise of the Phoenicians and Byzantines. While the briefings are delivered through voiced-over text (much like in the original Age of Empires), the actual scenarios feature myriad in-game cutscenes (with cinematic zooms and character interactions) and scripted events that try to give the impression of a dynamic landscape, not unlike Warcraft III released a year later. Although largely based on reality (including a recreation of how the Trojan War would have historically happened), starting with the final German scenario (which has you undertaking the infamous Operation Sealion), the plot also starts taking a turn for the fanciful. This is epitomized in the futuristic Russian campaign, which begins with the rise of Grigor Stoyanovich in the (then distant) year of 2018 and soon turns into a sci-fi adventure involving a world-conquering “Novaya Russia,” laser-spewing robots and time travel; while not quite on par with a Command and Conquer plot, the twists and characters are interesting enough to catch your attention. The actual scenarios, meanwhile, are lengthy affairs – towards the end of their respective campaigns, these can last for over an hour, depending on difficulty – with different mission objectives (with Civ Points awarded for completing them) and varied situations (such as a hero-centric stealth sections and epic-scale battles). But while these, alongside unique structures and units, prevent the action from being repetitive, they also come across in practice as more puzzle-like and less friendly to experimentation; as enemies tend be well entrenched or persistent, some scenarios can at best be tricky and at worst, devolve into trial and error in finding a specific solution. Which isn’t necessarily helped by what you’d hear while doing so.

The game’s audio, even for its day, is woefully uneven. The menu/intro theme (composed by Ed Lima and Steve Maitland) is memorable in how over-dramatic yet fittingly epic it is, complete with rousing orchestral moments and battle sounds. On the other hand, the rest of the soundtrack, though suitably atmospheric, doesn’t always seem to fit to the action on-screen and can quickly become repetitive over the course of a single match. Then there’s the voice acting, which could be described as either amateurish (with the noted exception of David Fielding of Power Rangers fame) or cringe inducing. This is especially evident when units and hero characters speak in with accents other than American, whether it’s the laughably bad French voices in the English campaign or the corny dialogue when playing as Novaya Russia. Coupled with somewhat canned sound effects, and the result drags the experience down more than it complements it, though it’s not without some unintended charm.

The visuals, utilizing 3D graphics through the Titan engine, have not aged well at all. On a technical level, Empire Earth very much looks like a product of its time. With the exception of walls and docks, structures are not fully rendered at all, which is disguised by a lack of camera rotation outside of select in-game cutscenes. The units themselves come across as blocky and lacking in much detail (be it low textures or having sprites in place of proper models), especially when zoomed in; the faces seen on infantry and Citizens are low-resolution pictures stretched across their heads unnaturally. The art direction, meanwhile, is generally solid, doing an ample job conveying thousands of years and some decent sci-fi aesthetics for the future portions to boot. This, is undermined, however, by how limited the pallet is, and not just simply with how some buildings are recycled in the campaigns (such as the Tower of London standing in for the Kremlin). With the exception of certain campaign-only buildings (such as Chinese pagodas), the aesthetics are largely Western, no matter what civilization you’re playing as; you could play as Japan, but still wind up with Roman-style soldiers or vaguely American fighter planes.

Then there are the flaws in the gameplay itself. The pacing of an average full match can be off-putting for some, especially as the early-game is heavy on just trying to get your economy functioning enough to “age up” from the Prehistoric Age. The tendency for the generally competent AI (or other players in multiplayer) to hunker down also means that matches can devolve into hour-long standoffs. The Civ Points and Civilization Builder features also only go so far in making each faction (custom or pre-set) distinct outside of stat bonuses; it doesn’t help either how, in addition to the Western-centric aesthetics, there are no playable unique units outside of the campaigns. The result is an experience that isn’t for everyone and not quite as grand as advertised.

These failed to stop Empire Earth from being a success. By 2002, it had sold over a million copies worldwide. Reception from critics at large was similarly favorable, many commenting on the similarities with Age of Empires positively, though some chided it for its less than stellar graphics and audio, among others. It also went on to win myriad industry awards, including GameSpy’s “PC Game of the Year” for 2001 and a “Gold Award” from German magazine PC Action.

RTS fans at large, meanwhile, also came to appreciate it. Despite not quite matching Goodman’s vision, Empire Earth was (and remains) seen as a classic in many gamers’ eyes for its solid gameplay and sheer ambition. Not many titles, even now, allow for real-time battles between knights in armor in a single match and lumbering laser mechs. Since its multiplayer servers went offline in 2008, a small but loyal fanbase has continued to sustain its presence online even while finding ways to make it compatible to modern systems.

Sierra, however, wasn’t quite done with the game just yet.

Empire Earth: The Art of Conquest – Windows (2002)

Even before the release of Empire Earth, Sierra already had plans for an expansion pack in mind. Unlike the main game, however, this would be made by Mad Doc Software (known as Rockstar New England since 2008) rather than Stainless Steel Studios; the latter would eventually enter a multiple title publishing deal with Activision in 2002. The new studio tasked by Sierra, however, wasn’t chosen out of the blue, as it had also been involved the original’s creation. Incorporating community feedback into their designs, the developers sought to deliver more of Rick Goodman’s winning formula while adding their own touches.

The result of those efforts is Empire Earth: The Art of Conquest, which came out on September 16, 2002 for PC; a Gold Edition (combining it with the original game) would come out on March 27, 2003. It was met with a rather lukewarm reception at best on release. But warts and all, it still manages to shine through.

Some of the most notable additions in the expansion can be found in the inclusion of a 15th Epoch: The Space Age. Set further down the timeline, this not only makes some of your structure even more futuristic or grants robotic Citizens. But it also opens access to new units and upgrades, many of which coincidentally tie to the introduction of space-based maps; building a Space Dock, for instance, unlocks spacecraft such as capital ships and corvettes with which to traverse the stars separating one “planet” from another. Combined with the ability to build a powerful Teleporter to quickly transport armies (albeit with some lag time), these add even more to the late-game and help make Empire Earth more distinct from the competition.

The other changes aren’t as immediately obvious, though are no less notable. The pre-set factions (which now include Japan and Korea) come with new “Civ Powers” this around, which can also be accessed for custom factions builds in the Civilization Builder. These Civ Powers are particularly varied and aren’t just limited stronger stat buffs (though some are available only for select Epochs), whether it’s the United States having an economy-boosting Market or Japan’s unique Cyber Ninja unit. While not quite substantial at a glance, these still help in making each side even more distinct. Meanwhile, apart from the space-related elements, there are also some graphical improvements compared to the original; tanks, for instance, now leave tread marks on a desert landscape, while artillery fire can create more evident craters on the battlefield. These are combined with new hero units and refined multiplayer options (including online matchmaking), resulting in a peculiar package that nonetheless retains much of what worked the first time around.

The Art of Conquest also comes with three new campaigns, though it’s around here that the execution stumbles. With a total of 18 scenarios (six for each), you get to witness the rise of Rome (from Marius to Caesar’s exploits), fight the Japanese in the Pacific theater of World War II and follow the travails of the Kwan Do family as it forges its legacy through colonizing (and freeing) Mars. Unlike Empire Earth proper and even Age of Empires, however, the presentation tries to be more documentary-like, whether it’s having the voiced briefings be excerpts from in-universe records or how the in-game cutscenes (which tend to be longer and with a bit more theatrical flair this time around) seem to be told from a more neutral perspective. In practice, this makes the actual scenarios – though just as challenging, if tricky as those in the original game – feel more detached and somewhat out of place for how there’s less to feel invested in. This isn’t helped by how the Roman and Pacific sections come off as retreading the Greek and German ones (at least the latter half) except with new palettes, as well as how the new voicework sounds either uninspired or plain bad. Nor how some of the scenarios can come off as unfinished, such as unvoiced lines of dialogue and the rushed nature of the final chapters of their respective stories; the Asian one infamously has no ending or so much as a final cutscene whatsoever, despite the epic “Mars vs. Earth” conflict being set up.

This isn’t to neglect some of the other flaws that become apparent the more you play. Civ Powers are rather unbalanced and can be stacked over in the Civilization Builder, easily resulting in custom factions being potentially overpowered; China’s “Just In Time Manufacturing,” for instance, not only allows for insta-building units for extra cost, but spans every Epoch, meaning that it lasts an entire match as opposed to many other Civ Powers. Meanwhile, the much-touted Space Age elements are woefully wasted, with spacecraft (save for Space Fighters) acting like naval vessels and the void of space itself being nothing more than a sci-fi palette swap for water; that there aren’t as many upgrades and aesthetic changes as there would otherwise be in previous Epochs also give the impression of these being half-baked. The new unique buildings and units, though useful, also don’t go far enough in breaking original game’s “sameness” issues or leave as much as their presence suggests. Thus, at points it can feel like you’re playing a glorified mission-pack more than anything else.

It’s no surprise, then, why more than a few reviewers brought up how The Art of Conquest either didn’t offer much to justify its $30 price tag or was generally disappointing, using many of the same points. This inevitably led to a very mixed reception upon release, garnering a 66% on GameRankings and 63% on Metacritic. Gamers were similarly torn over the expansion at the time, as it didn’t seem to live up to the standards set by the original game.

Yet despite the criticisms, The Art of Conquest was still praised for retaining much of what made the original such a hit, with Gamespot even applauding the audio. As part of the Gold Edition, its features and additions came to be more appreciated by fans for how these added to the overall gameplay; flawed in execution as they were, being able to use SAS Commandos as the UK or fight bombastic space battles remained enjoyable. Neither did the lukewarm reviews damage Empire Earth’s reputation in the long run.

More than just becoming a classic, with fans looking back with nostalgia, the game continues to have a small yet loyal fandom. Not only would these fans be responsible for various modpacks (whether gameplay tweaks or graphical mods) and custom scenarios, many hosted by HeavenGames. But they would also help keep Empire Earth alive online long after Sierra’s servers were shut down on November 1, 2008. Whether through third-party applications like GameRanger or fan-made lobbies such as NeoEE, you’re still likely to find players duking it out now as back in 2001.

Its initial time in the sun, however, was not to last. On May 6, 2003, a few months after the launch of the Gold Edition, Big Huge Games’ Rise of Nations was released to the public. A unique, if even more refined blend of Age of Empires and Civilization, the praise lavished on that Microsoft-published RTS (both from critics and gamers) soon stole the proverbial thunder from Empire Earth.

Sierra and Mad Doc Software would eventually return with a proper sequel. But that is another story.