- Psychic 5

- Esper Boukentai

- Psychic 5 Eternal

In the 8-bit era, several hybrid genres were developing, but none more prominently than action-adventures. The Legend of Zelda had brought it to popularity, but there were so many different subsequent takes on the formula. Some added RPG elements in varying degrees, whereas others changed the perspective from its top-down origins. Perhaps the strangest beast of them all was the side-scrolling variant, which made the action much more fluid than with the overhead perspective, but brought a slew of problems all on its own. The most prominent issue with this style of gameplay was in building a big, rich world that was also easily traversed and explored. Since this had no single obvious solution, there were an incredible number of different approaches, until the games industry did what it always does: finding one that works and stick to it like an immutable formula.

The question that needed to be answered: How does one create a side-view world worth exploring without just making it into one long, flat drag from one end of the world to another? Some games, like Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest and Lord of the Sword actually don’t answer this question, making their worlds mostly a straight run, thereby making backtracking an absolute chore, though to be fair, Simon’s Quest did use staircases in its dungeons to round them out. Games like Blaster Master and Metroid throw in a bunch of platforms, the former keeping the levels relatively flat, and the latter making players groan whenever they enter yet another overly long vertical section. Some, like the NES version of Rambo, treated the world as though it were overhead, giving the player northern and southern paths to different trails, creating an illusion of depth, so to speak. The Battle of Olympus and Jikuu Yuuden: Debias did something similar, but implemented it with caves and doorways. The Legend of Zelda‘s own sequel, Adventure of Link, separated the game into different side-scrolling sections by having an overworld map to connect them all. Esper Boukentai decided to solve the problem with one of the most creative, obtuse, and flat out bizarre ideas ever: moon jumping.

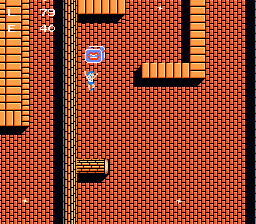

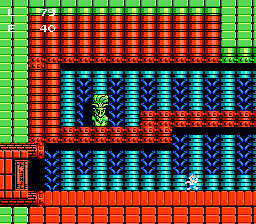

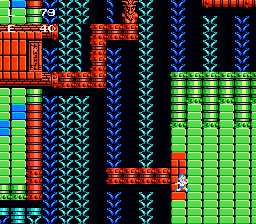

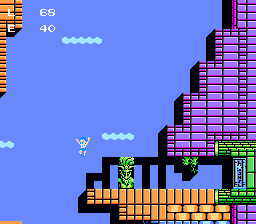

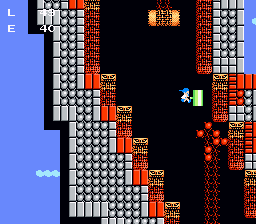

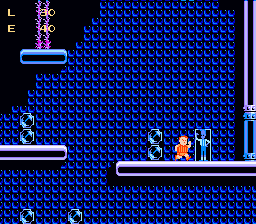

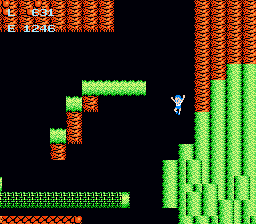

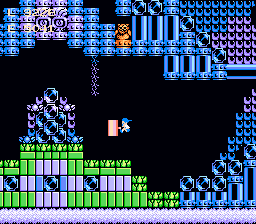

Now, jumping higher than is realistic in video games is absolutely nothing revolutionary. Super Mario Bros. lets you jump pretty high; Psychic 5, the game’s own spiritual predecessor, lets you jump even higher; the little-known Low-G Man carries in its name how high its protagonist can jump. The protagonists’ jump heights in these games are all just pathetic compared to that of Esper Boukentai; the first, well-rounded character can jump more than two whole screens upward in a single leap at the beginning of the game. Like in Psychic 5, you can hold down to jump lower, as well as hold up to float downward, though this time, jumping higher requires only holding the jump button. As your level increases, your jump gets even higher, reaching heights that seem nothing short of impractical.

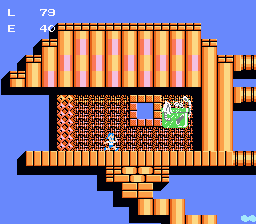

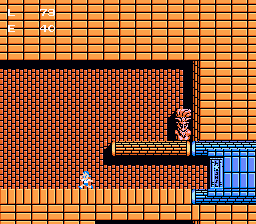

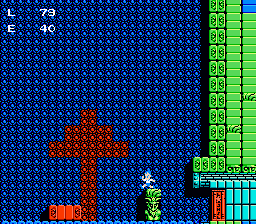

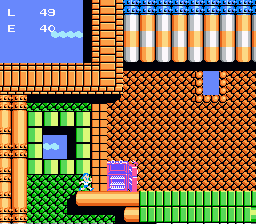

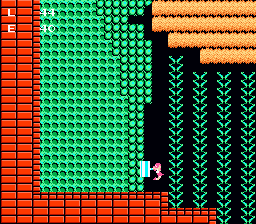

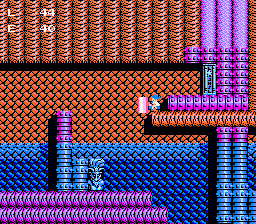

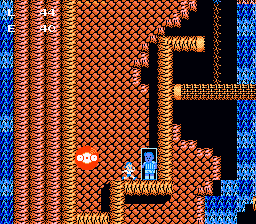

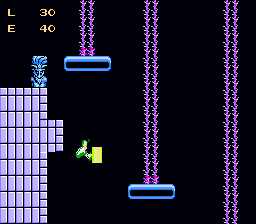

So how well does this solution actually work? Well, like the game’s overall quality, it’s so simultaneously good and bad that it’s hard to say for sure. The castle in which the entire game takes place is, at the very least, competently designed around your jump height. Pitfalls are back, but placed in such a way that you can’t just leap immediately back to where you were, thereby making them actual hazards that still warrant inclusion. The other neat thing about the level design in relation to your jump is that certain areas require impossibly high jumps until you find a higher jumper – now hidden behind crystal blocks, rather than in jars – or increase your level. At any rate, the moon jump does its job of getting you around the game’s world efficiently.

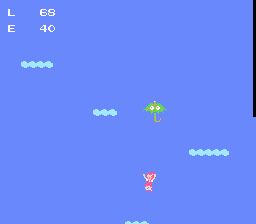

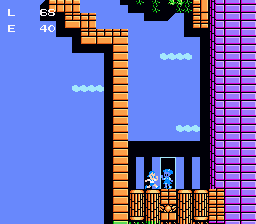

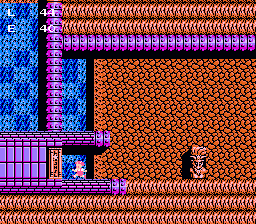

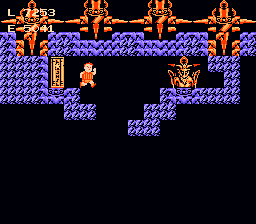

While it is great for exploring, the moon jumping causes a new problem that can end the game very quickly. Forget how awkward combat is in Psychic 5, because Esper Boukentai makes it excruciating with any normal kind of strategy. Your jump is much higher, making it easier than ever to overshoot your enemy, and this time, the cartoony inanimate objects with googly eyes not only fly upward out of your way as you jump toward them, but also spawn mass amounts of fast-moving homing projectiles that can stop your heart in half a beat. You can dispel them en masse with a swing of your hammer, but getting it to connect isn’t so easy. It is possible to become competent and even good at combat, but it takes a lot of practice; the best strategy is to engage enemies in enclosed spaces, where you can pin them against the ceiling. That way, when you jump toward them, they have nowhere to go vertically, and once you meet them, you can keep yourself in the air by repeatedly wailing away with your hammer, just like in Psychic 5. It’s by no means perfect, of course, but with enough practice, you can fairly easily defeat most enemies without taking a single hit.

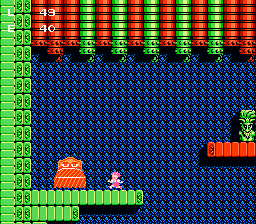

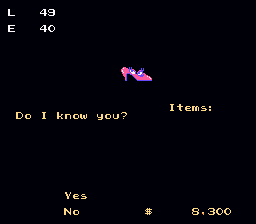

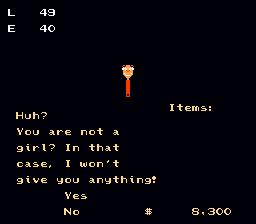

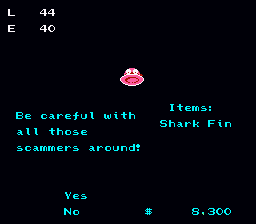

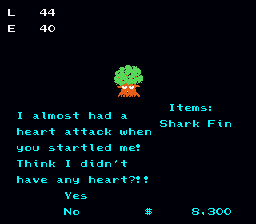

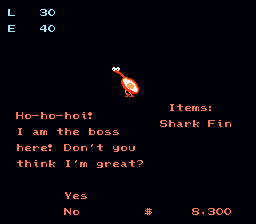

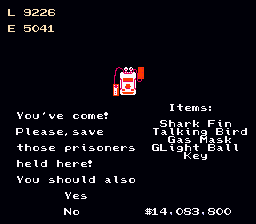

This time, you may not want to fight every single Pee-Wee’s Playhouse-conceived nightmare; some of them are actually quite friendly. In fact, the denizens of the castle come in three varieties: helpful, aggressive, and jerk. By pressing Start, you can engage any being in conversation, which will sometimes give you choices. Some will help you by giving hints, money, or items. Others will attack you afterwards, but since they’d have attacked you anyway, it’s no big loss. The ones you really have to mind are the third variety; they seem nice at first, but all they want is to scam you out of your money, which is very important in this game.

Money is used to buy items that are necessary to finish the game, as well as restoring of your life and esper power. That’s pretty standard, of course, but what isn’t so standard is that there is a virtually finite quantity of money in Esper Boukentai. For the most part, you can only find money in treasure chests; there are two beings – a spoon and a candy jar – that will give you a very small sum of money whenever you talk to them, but the amount is so negligible that it’s best to hope that you don’t have to resort to that. Worse yet is the fact that you lose two thirds of your total every time that you die.

The varying temperaments of the sentient furniture will provide you with a dilemma each time you encounter one. You can speak to or attack each and every single one of them, so unlike in most games, your course of action is less than crystal clear. This decision is made all the more difficult by the fact that even some of the friendly enemies move in a way that suggests aggression, so you never really know what’s going to come out of each encounter. You can certainly smash everything to death, just to be sure, and while the game doesn’t punish you for doing so, it also doesn’t reward you; killing a friendly creature will not bring you any experience points.

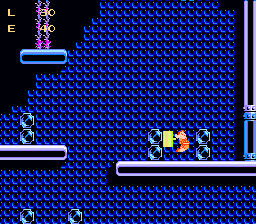

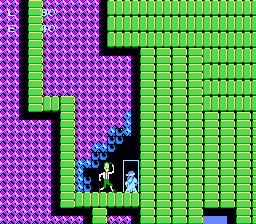

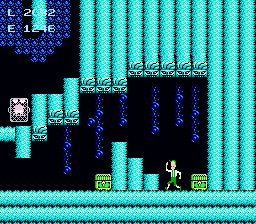

It is also rather easy to bring them back; like in Psychic 5, each room is broken into several different spawn zones. This seems to be a function of the hardware’s limitation, in order to limit the game to only one or two of the considerably large sprites on the screen at a time. Whatever the reason, all you need to do is move in any direction until you hear the audio cue, telling you that you’re in a different zone, and then move right back into it again. This can also be exploited when grinding; there’s a spot in the Ice Room where you can just edge off of a platform and get right back on before falling, spawning two new enemies; you can reach your maximum level in a very short time by doing this.

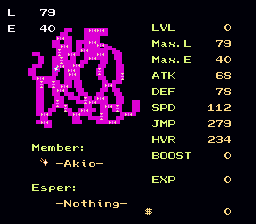

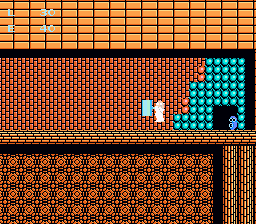

Leveling up raises your stats, but this brings a lot more to the table than usual in this kind of game. Of course, it governs your maximum Life (hit points), Esper (magic points), attack power, defense, and movement speed, but it also governs your jump height, the speed of descent when hovering, and “Boost”. Boost is a stat that takes some time to figure out; it doesn’t seem to affect anything, and always remains curiously low, never increasing beyond three. What it does – oddly enough – is determine which doors you can or cannot open. Doors do not open just by touching them; you must first touch the corresponding idol in the room to unlock a door. You’ll get an audio cue telling you whether or not you can open the corresponding door, and that is determined by your Boost value, which is shared among all characters, like Life and Esper. It may seem a bad decision to require the player to grind in order to open certain doors, but this ensures that you are of an adequate level to tackle the baddies in the ensuing area.

Keeping to the theme of bizarre design choices, even leveling has its share of oddities. Your hammer is a different color at each level, so that you can always tell what it is without entering the menu. Despite that, your level will never increase after reaching the required number of experience points unless you enter the menu, whereupon you will be treated to a fanfare and a message telling you that you’ve done so.

Strangest of all is the Esper stat. Magic points are a very familiar concept in vide games, but in Esper Boukentai there only seems to be one single special power in the entire game to use them: Stormball. Despite its impressive name, it is nothing more than a rotating shield that drains your Esper with time. Given that there is no knockback in this game and that the hit detection is especially sketchy with this power, it is effectively useless, and with it, the entire Esper stat.

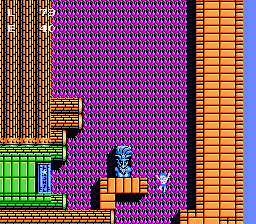

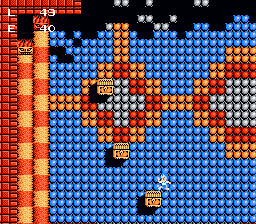

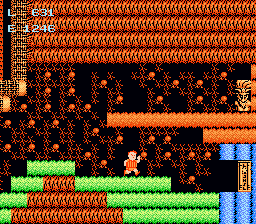

Even the audiovisual department is a mixed bag. The music is pretty hit or miss, but if you listen closely, you can recognize some of the characters’ themes from Psychic 5. What makes it so strange is that talking to a denizen or even sometimes moving between zones will change the music completely, giving you the “wrong” music for the area. The visuals are very difficult to assess. The bright colors are quite lovely when contrasted with a pitch black background, but it seems that The Devil’s interior decorator forged some of the backdrops and their textures from the very fabric of chaos; there’s blank space, zigzags, bricks, logs, and some of the most unusually-patterned wallpaper this side of the 1970s all in the same screen, and that’s not even the worst of it.

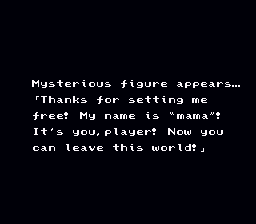

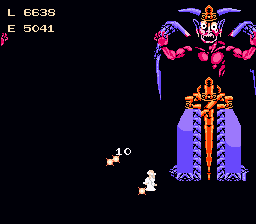

Story in such an old game is almost never anything that’s going to change your life in any meaningful way, but it was clever for what it was, and the conversations were entertaining. Save your friends and a mysterious prisoner from The Devil’s castle was all that this game needed, and the ending is enough to elicit a chuckle. You open the final door and discover that the mysterious prisoner is you. That’s right: you saved yourself from imprisonment by the evil overlord; go outside and play with your friends or something. Okay, so maybe it will change your perspective on life; it’ll make you take that important step back and say to yourself, “What did I just do with the last few hours of my life?”

Esper Boukentai was never released in English, but there is a fan translation patch that makes the dialogue accessible. While it was a Famicom exclusive in the day, it has been released on the Japanese retro game platform Project EGG.