Among Fallout fans, there are two conflicting ideas about what Fallout actually is. To many players, Fallout is about exploring the post-apocalyptic wasteland, shooting raiders and participating in conflicts which will shape the future of the world (or rather what remains of it). Others will say it’s not enough – for them, Fallout is a game about difficult choices, complex mechanics and extreme non-linearity.

Such divide among the fans stems from the fact that Fallout can be thought of as two loosely connected series developed by different teams with different approaches to both gameplay and narrative. The first two mainline games are a product – or maybe a catalyst – of the 1990s computer RPG revival and carry all the common traits of this movement. They’re played from isometric perspective, they put a lot of focus on player agency and their difficulty is less in choices made during the combat and more in preparation and character building. Fallout 3and 4, created by Bethesda, are more similar to that studio’s flagship The Elder Scrolls series (especially later titles like Oblivion and Skyrim): they’re exploration-heavy first person action-RPGs set in a large, freely explorable (due to both lack of explicit ‘invisible walls’ and the controversial level scaling mechanics meant to provide steady difficulty during the whole playthrough) open world.

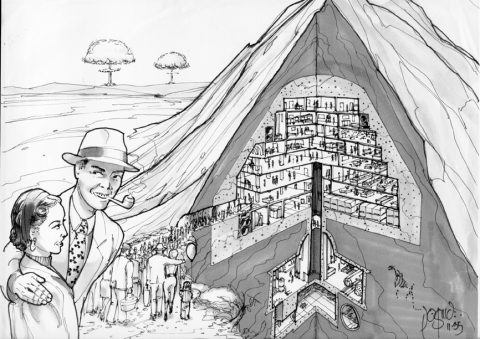

As different as the games in the series can be, they always contain a few common elements: SPECIAL (Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility, Luck) character building system, an outsider protagonist who can change lives of different communities but never belongs to any of them and a memorable Fallout setting: a retrofuturistic (1950s style: vacuum tubes, huge computers and bulky mechanical devices) world of nuclear-powered cars, laser guns and household robots devastated by a global conflict which killed the majority of population and reduced the survivors to scavenging the ruins of old civilization while trying to rebuild the world. It’s a world where what remains of the optimistic ‘raygun gothic’ sci-fi is locked in massive underground shelters (‘Vaults’) while the outside world looks like something between the wild west and Mad Max. It’s the world which tried to pretend it’s still golden age even as it descended into a nuclear war, leaving behind both commercials full of smiling people and irradiated craters crawling with mutated beasts.

Originally, Fallout was supposed to be a sequel to Wasteland, Interplay’s older post-apocalyptic RPG. When the company wasn’t able to acquire rights to the title from Electronic Arts, they decided to look for a different license and started working on a game with similar setting based on the rules of a tabletop RPG GURPS. When the deal with GURPS publisher fell through during the game’s development (apparently, due to the game’s violent content), Vault 13: A GURPS Post-Nuclear Adventure was retooled into Fallout: A Post Nuclear RPG, SPECIAL system was created and the series as we now know it was born.

During the development of Fallout, Black Isle Studios created a set of simple rules which would then define the most important things about the experience. According to those rules, each problem encountered by the player should be possible to solve in multiple ways, each skill should be useful, the game should use dark humor but not slapstick, different playstyles should be possible and decisions should have consequences. Despite the fact that every game occasionally broke some of those rules, there’s no doubt that they were extremely important for early Fallout games: those general ideas which drove the development were the same things that fans of the series appreciate the most.

Fallout soon gained a large cult following which not only warranted a sequel but also started something which can be described as a new subgenre of RPG: after Fallout came a number of Fallout-like games which borrowed its many recognizable elements: gameplay heavy on stats and skills, freeform character building not restricted by predetermined classes, multiple solutions to almost every quest and endings which consisted of multiple independent segments coming together to show how player’s choices helped shape the game’s world. While games like that are still being made by small but dedicated indie teams (see recent UnderRail set in the tunnels of a massive metro system and Age of Decadence in which the post-apocalyptic future doesn’t look to different from ancient Rome) and even bigger budget titles adopt some of those elements (e.g. the Fallout-style multiple endings in Pillars of Eternity), to this day the most remarkable Fallout-like has to be Arcanum created by many of the same people who made Fallout.

Unfortunately, the early XXI century and the decline in popularity of traditional cRPGs that came with it weren’t kind towards the series and after the third game was cancelled and a few unsuccessful spin-offs were released, Interplay had to sell their intellectual property. A few years later, the franchise was, depending on how you look at it, either rescued or destroyed by Bethesda with their take on the series which brought in millions of new fans but also strayed far from the rules which governed the design of the first two titles.

Nowadays, Fallout is a multi-million dollar franchise with a strong, creative fan community. It is one of the most popular RPG series, with the ‘Vault Boy’ character (a cartoon man used as a visual representation of various game mechanics and other aspects of the series) being an instantly recognizeable icon. Fallout games are among the most popular targets for modders who do everything from fixing bugs and restoring cut content to completely reshaping the games.

Links:

Official website

Fallout Wiki

A brief history of Fallout at Eurogamer

Why Fallout is the best nuclear war story ever told at Medium

Fallout begins with a short intro cutscene showing pre-apocalypse television: advertisements of Vaults, nuclear-powered cars and ‘Mr. Handy’ robots as well as a news segment in which soldiers in power armor execute a man before waving towards a camera. The whole thing is set to ‘Maybe’ by The Ink Spots. After that, camera zooms out from the TV and we’re shown ruins of a city, followed by opening credits and a slideshow of war-themed photographs. This segment also contains the famous ‘war never changes’ speech performed by actor Ron Perlman which both provides insight into the history of Fallout’s universe and highlights the game’s main themes. Such introductory videos and narrations would become an obligatory part of each game in the series (the mainline titles at least) but they’re the best here, in the first game: the hypocritical optimism of pre-apocalypse world is both funny and scary, Perlman’s monologue carries a lot of weight and in a few short minutes we’re given a lot of background on the world of Fallout without any obvious exposition dump.

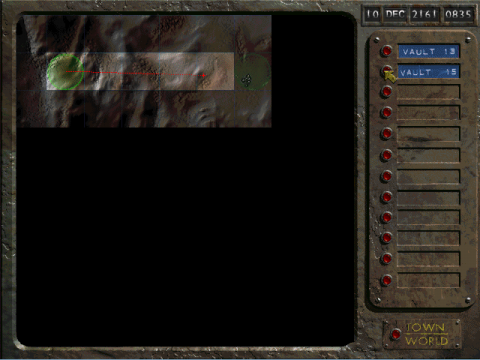

Fallout does a lot of similar things in its early stages: the difficulty of your quest is established by the remains of previous explorer just outside of the Vault doors (‘You see Ed. Ed’s dead.’). As you move towards Vault 15, there’s a small town called Shady Sands between you and the goal of your quest which serves as a tutorial area showcasing many important mechanics in an easy to understand way (although the game is so complex that you’ll probably want to read the manual anyway): holstering your weapons in civilian areas, bartering, town maps, NPC recruitment (Ian), status effects (radscorpion extermination quest), time-based events (‘rescue Tandi’ quest) while the very fact that Shady Sands is there shows that you can discover unknown locations by exploring the map. From the storyline perspective, it’s not too important (with an exception of one of the town’s endings which sets up a major political power for future games) but you do learn that the communities in the game’s world are independent, that people make a living by farming and scavenging and people need to fight against both mutated beast and gangs of raiders who terrorize local towns.

The game’s protagonist is Vault Dweller: an inhabitant of Vault 13 sent into the outside world to get in contact with other Vaults in hopes of finding a replacement for a broken water purifier chip, a device essential for the Vault’s survival. The game allows you to pick from three premade characters (one for each of combat, stealth and diplomacy archetypes) but it’s generally more fun (and better, when you figure out how to properly build a character) to create your own Vault Dweller. That’s because the story of Vault Dweller is a one driven by the player, not by the developer – the game’s design aims to give the players tools to express themselves by making decisions and designing their own character’s skills and personality. The story of Fallout is not set in stone, it reacts to the character you as a player create.

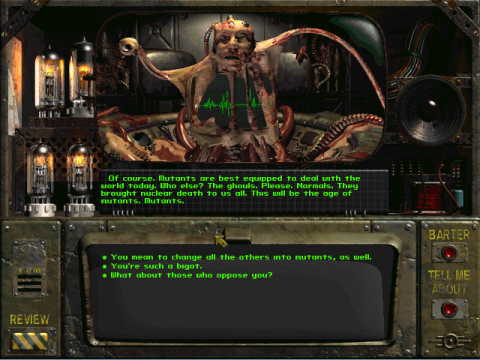

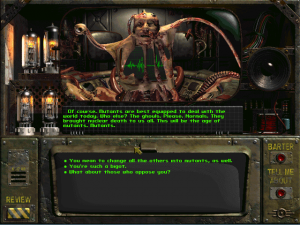

Fallout’s main storyline begins with the search for water chip but later focuses on the threat of an army of super mutants. Famously, the conflict is not just about overcoming the powerful enemy but also about the ideas behind it: are humans equipped to survive in the post-apoalyptic environment? Is the survival of humanity even a good thing or will it lead to another destructive war? Are mutants the future or just an evolutionary dead end? While the final boss can be defeated in combat or through sabotage, it’s also possible to either join him or convince him that his plans can’t succeed. Unusually for an RPG, all main objectives in Fallout have a time limit – if your search for the chip takes too long, inhabitants of Vault 13 dies and it’s game over. In the game’s second half the limit is more generous so it’s hard to lose because of that but the longer you take, the further the mutant army gets which leads to getting a bad ending in more towns.

But the main story, while generally good, isn’t where the game really shines. No, the best thing about Fallout is all the little stories you find when exploring the wasteland. Each of the places you visit has its own – mostly self-contained – plot about people living in the world after the fall of civilization. There’s Junktown with its conflict between a righteous mayor and a rich casino owner who works with locals criminals (originally, the ending was supposed to be better if you don’t help the mayor as he would become a power-hungry tyrant to highlight that a seemingly obvious moral choice can have unpredictable consequences but it was changed before release), there’s a trading town called The Hub which suffers because someone or something is attacking their caravans and there’s the aforementioned Shady Sands and their trouble with Road Warrior-style raiders. The best of them has to be Boneyard though: a town on the ruins of Los Angeles ruled by a corrupt militia called The Regulators, with a questline potentially leading to player character arming local rebels and helping overthrow the bad guys in a huge showdown in which everyone on the map joins the fight (unfortunately, this means that actually playing through the whole thing requires a whole lot of waiting for all the combatants to make their moves).

Separate, unrelated plot threads of Fallout work together to form an internally consistent world: a disorganized post-apocalyptic West Coast where immediate survival is still an issue but the question about how to rebuild the world is becoming increasingly more important. Scavenging and hunting are common but so is farming (two-headed cows called brahmin are a common source of food) and trading (brahmin are helpful once again as they can pull wagons made from broken cars). NPCs in Fallout are often preoccupied with finding necessary supplies but they also try to create rules for their new communities, even if they can never agree what kind of rules they want. The different ideas are exemplified by a few ‘global’ factions whose influence goes beyond single towns: Brotherhood of Steel which aims to protect old world technology (often from other inhabitants of the wasteland), Followers of the Apocalypse who want to bring peace so that the next apocalypse won’t happen and Children of the Cathedral who value unity above anything else.

Fallout is a turn-based RPG played from an isometric perspective, with maps placed on a hex-based grid. The game has a tactical combat based around the concept of action points, which means that each turn can include amount of movement, attacks, reloading weapons and access to inventory and the player has to maximize damage dealt to enemies, healing and defense (unspent action points are added to armor class – which is the opposite of the old Dungeons and Dragons armor class so you want it to be as high as possible – for the remainder of the round). Spending an additional action points on an attack allows targeting of specific body parts to either reduce the enemy’s combat effectiveness (e.g. they’ll get less action points after having their legs wounded and their aim will be worse when you damage their eyes) or do extra damage. Some weapons also have an optional automatic firing mode which quickly kills everything in your way (enemies killed this way will often have a special gory death animation) but is less accurate, often resulting in civilians or your companions getting shot instead of the enemy.

Combat effectiveness of each character depends on a set of different stats and skills: strength influences unarmed damage, perception gives a better hit chance, endurance determines the number of hitpoints, more agility means more actions per round and high luck makes it easier to hit critically and harder to drop your weapon or damage yourself. Different weapons also have skills associated with them which means that the player is able to get better at using them as the game goes on (skills are increased on level up while SPECIAL stats generally stay the same for the duration of a whole game, outside of a few scripted ways to gain them and loss related to wounds and radiation sickness). In addition to stats and skills, the game also has traits chosen during character creation and perks gained while leveling up which affect the player character in more specific, sometimes unique ways.

Stats, skills, traits and perks in Fallout are related not only to combat but also to other aspects of gameplay. It’s possible to build a completely non-combat character and rely on persuasion, stealth and knowledge. While a truly pacifist playthrough might not be possible as solving the main quest will cause a few deaths one way or another, you can do everything with dialog and skill checks, without once throwing a punch or using a weapon. Fallout is all about choice and if the player choses not to be an action hero, it will respect that decision.

Most of Fallout’s visuals have aged well. While the isometric graphics are nice consistently good, the best thing about the game’s look are ‘talking heads’: special animations shown during dialog with important voiced characters. Those were created by digitizing actual physical clay models and animating them, which made everything look a little different from the usual low-poly 3D graphics of the time. Some of the interface elements look really great as well: vacuum tube amplifier through which the conversations are played, menus based on mechanical buttons, even the analog display in every elevator. The only thing that looks kind of bad are movement animations which seem very unnatural due to hex-based pathfinding (it doesn’t help that they’re rather slow in combat which gives you a lot of time to look at everything that’s wrong with them).

The game’s soundtrack made by Mark Morgan consists of dark and atmospheric ambient music. It does its job but unlike with the composer’s Planescape: Torment soundtrack, only a few tracks (e.g. the ones that play in Mariposa and Boneyard) are memorable outside of the context of the game. Unfortunately, those tracks are also the ones that don’t seem to be entirely original as Mariposa theme seems to contain samples of Brian Eno’s Alternative 3 while the Los Angeles music is very similar to Grass by Aphex Twin. The game seems to use sampled music in other places as well, although those tracks are brought up most often as the similarities are the most obvious. Sound effects and voice acting (used only for certain characters as most are text-only) are generally very good, with the latter having a few noticeable highlights like the intro speech or dialog with The Master.

On a technical level, Fallout is mostly competent which would later prove to be an exception rather than a rule as the games in the series are known for their bugs. There are some issues with combat AI (both enemies and companions will fixate on one opponent and will fight him until one of them dies, even if the said opponent is running away while somebody else is shooting them in the back) and one of the endings becoming inaccessible but otherwise, the game plays fine. On modern computers, the game is playable (albeit with an occasional crash due to memory management issues) as newer releases include widescreen support although it is better to turn the resolution down as it doesn’t scale things, it just draws more of them on the screen.

Fallout is an amazing game and one of the most important RPGs of its time. Its systems are well designed, its worldbuilding its brilliant and the amount of meaningful choice it gives to the player is just impressive. While its interface takes a while getting used to (although it quickly becomes second nature) and the complexity means that it’s not a game you just pick up and play, it becomes insanely rewarding after you learn how to play it. It’s not as big of a time investment as one may think anyway: the game is much shorter than other mainline Fallout titles.