Released not long after the first game, Fallout 2 is in many ways similar to its predecessor. The game reuses Fallout’s engine (with some modifications) and many of its assets so it both looks and plays like Fallout. What makes the sequel different from the original is an increased scope (not only is the game world much bigger, most of the towns now have multiple optional quests of interconnected chains – many of them requiring travelling from one place to another), sillier tone and a story which builds on the themes from the previous game to show next steps in the process of rebuilding the world.

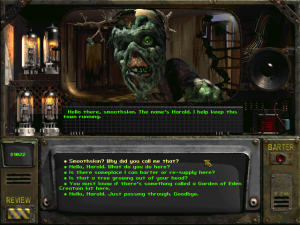

After the events of Fallout, Vault Dweller founded a village called Arroyo. Due to its remote location, its inhabitants developed a tribal culture isolated from the outside world in which stories about the life of the protagonist of a previous game became legends. Player character in Fallout 2 is The Chosen One: Vault Dweller’s grandson tasked with finding ‘holy GECK’ (Garden Of Eden Creation Kit) – a device which allowed people living in the Vaults to make plants grow in the wasteland, making it possible to once again live on the surface. Despite the mission being set up in a similar way to the water chip quest from the previous game, this time there’s no urgency – The Chosen One will not be able to find GECK in time and in the end he’ll have to save Arroyo from a very different threat.

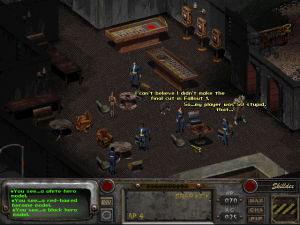

Fallout 2 introduction is stylistically similar to the beginning of the previous game, although the purpose seems different: while everything from Vault 13 to Shady Sands worked as an unintrusive tutorial, Temple of Trials and Klammath are designed in away that is rather challenging for those used to the previous game: getting your first gun takes quite a long time and it has to be reloaded after each shot, status-inflicting enemies are more common and the only way of healing that is both reliable and affordable temporarily reduces perception. In other words, a high-endurance melee fighter stands a better chance of surviving early quests than a typical gunslinger. Annoyingly, the rest of the game still favors ranged combat so you need to choose between annoying combat in the beginning or annoying combat near the end.

Like its predecessor, Fallout 2 is less concerned with an overall plot and more with the smaller stories of different post-apocalyptic communities. A big difference is that now they’re not completely separate: quests often require travel between settlements on diplomatic or covert missions and the endings for many of the towns are influenced by what happened elsewhere. This makes sense as the problems they’re dealing with have a larger scale: expansionism, organized crime, pollution.

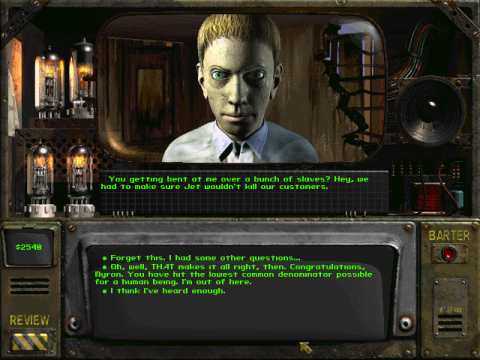

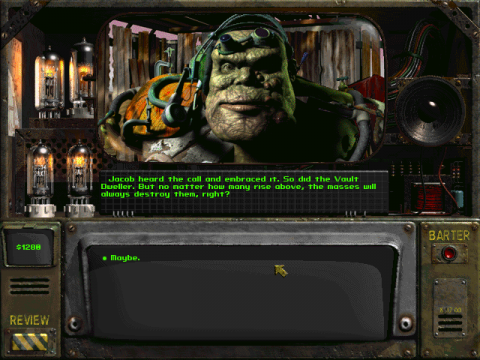

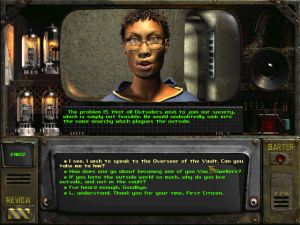

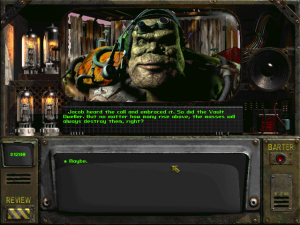

Communities in Fallout 2 are a bit uneven when compared to the first game but there’s no denying they have a lot of personality to them: places like New Reno with its conflict between four criminal families (and a huge number of possible endings), New California Republic (based on one of the possible endings for Shady Sands in Fallout) trying to rebuild old America, bureaucracy and elitism of Vault City or the surprisingly good human-mutant relations in Broken Hills are all interesting and memorable. Unlike in first Fallout, the same amount of character was given to recruitable NPCs so you can now travel through the game’s world with a ghoul (not really undead – ghouls in the world of Fallout may look and move like zombies but they’re mutants and most of them act just like normal humans) medic, a super mutant sheriff, a tribal warrior who communicates with spirits, a cybernetic dog or an intelligent but evil teenager responsible for the creation of an addictive and destructive drug Jet.

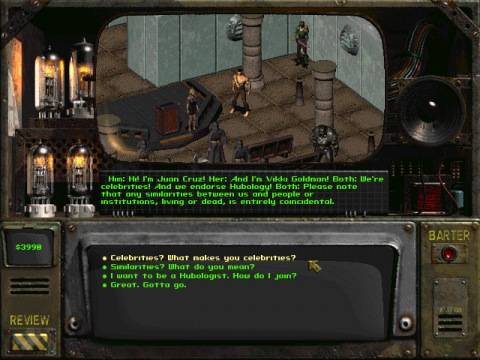

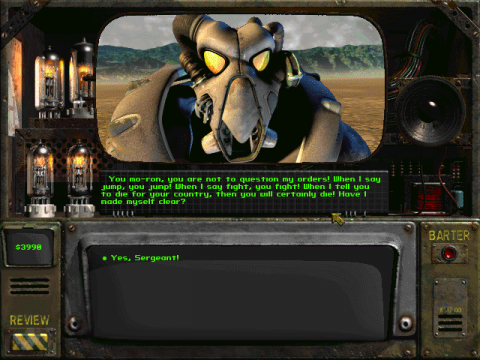

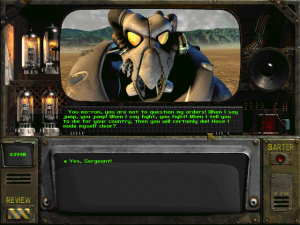

In many ways, Fallout 2 attempts to outdo Fallout by adding more of the things that made the first game memorable: more towns, more companions, more secrets, more special encounters, more large-scale battles, more weapons, more humor. As a result, the game feels serious than its predecessor. The protagonists ‘fish out of the water’ status is much more pronounced and some parts of the game – especially in New Reno – feel like a post-apocalyptic version of a story about a teenager from the province coming to the big city, with all the sex and drugs-related implications it usually carries. Most of the humor in Fallout 2 works well but it does have a tendency to overdo it with references (although to be fair it’s nothing new for the series – even in the first game you could randomly find things like TARDIS from Doctor Who or a corpse of someone squashed by what seems to be a Godzilla-like monster). The funniest thing has to be the angry sergeant you can meet while infiltrating one of the late-game locations who thinks you’re an incompetent soldier and berates you for not having a uniform, not guarding a hangar or not having proper documents.

Sex, drugs and violence of Fallout 2 made the game rather controversial at release. The biggest source of outrage was the fact that the player is able to kill children (even though an action like that is never encouraged and leads to a major reputation loss). Because of that, many versions of Fallout 2 are censored – often in a really stupid way which doesn’t remove the children but makes them invisible, meaning that the player can earn a childkiller reputation by a complete accident.

While most of the gameplay is kept similar to the first game, there’s a noticeable difference in how some of the stats and skills work. Charisma is now much more important as it determines your follower limit. Random encounters are far more difficult so outdoorsman skill can come in handy, especially near Vault 13 and San Francisco as enemies there (remnants of Master’s army and Enclave patrols respectively) can be extremely deadly. The game also offers a bigger choice of perks, although the useful ones tend to be the ones that already existed in Fallout and were useful there.

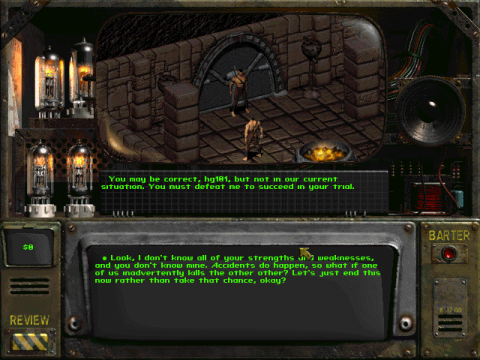

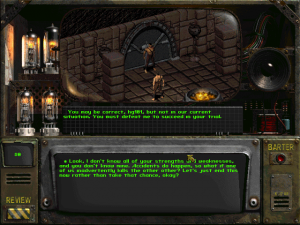

Encounter design is a big step down when compared to Fallout: the difficulty of many of the fights is based purely on the fact that they have a large number of enemies who do a lot of damage and have a lot of health. This leads to some of the fights (especially in the early game when you’re not well prepared and in the late game when the enemy difficulty is ramped up significantly) becoming extremely tedious: clearing Wanamigo mine or fighting through the tanker’s lower deck is not easy but it’s also not fun. The developers also seemed to have learned the wrong lesson from Fallout’s big fight in Boneyard as many of the random encounters now contain groups of NPCs (both hostile and non-hostile towards the player) facing off against each other – unfortunately, when it happens so often and without any sort of context it just doesn’t carry the same weight; also, it’s as slow as it was in the first game which means that using anything other than the fastest combat speed setting will make those battles insufferably boring. The final boss is easily the worst about it as he has maximum possible number of hitpoints, all stats maxed out and is equipped with unique (and extremely powerful) weapons. Of course this is still a Fallout game so you don’t need to fight him directly (although this time a purely diplomatic solution is not possible).

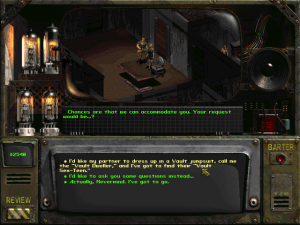

One of the coolest new additions to Fallout 2 is Chrysalis Highwayman – a broken nuclear-powered car you can repair through a lengthy quest. It might not have a big impact on the gameplay (basically, you can travel faster between the times and put heavy items in the car’s trunk but you need to refuel it with sources of energy which could otherwise be used to power energy weapons) but there’s just something amazing about driving a rusty muscle car through the post-apocalyptic wasteland while the game’s only guitar-based track plays in the background. As The Chosen One puts it (referencing The Blues Brothers): ‘it’s 106 miles to Arroyo, we’ve got a full fusion cell, half a pack of RadAway, it’s midnight, and I’m wearing a 50 year old Vault 13 jumpsuit. Let’s hit it’.

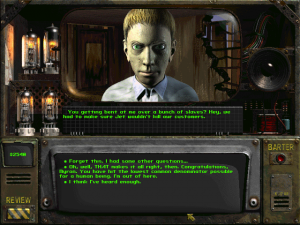

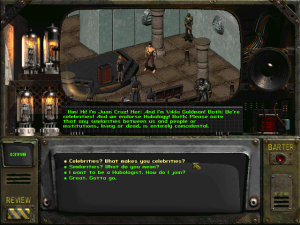

Another interesting – and much more substantial – change to the gameplay is the revamped karma system. In addition to the general karma score, the player now earns separate reputations in different places. The game also allows player to obtain reputation perks with unique (positive or negative) effects by performing specific actions like joining the mafia, becoming a slaver or starring in a porn film (Fallout technically had this feature too but there only very few of those and their effects weren’t noticeable).

Fallout 2 is an extremely buggy game. While some of the most obvious issues (like the car’s trunk following the player like a companion) were removed through official patches, most of them weren’t and the differences between Windows 95/98 and modern operating systems make some of them even worse. Some of the game’s endings are inaccessible (e.g. it’s not possible to get the good ending for Vault 13), some temporary allies become hostile on accidental friendly fire and they make their whole town hostile as well (watch out for that when protecting the caravans) and the AI quirks are as exploitable as in the original Fallout. On modern systems, memory-related crashes are common and the game can hang up when calculating NPC movements during combat – it usually recovers but given how often it happens, it makes random encounters even more annoying. It is highly reccommended to play the game using unofficial bugfixes.

It’s hard to say if Fallout 2 is better than the original or not. It’s certainly less focused and much less polished, suffering from very short development time. On the other hand, it’s also a very ambitious, deep and complex game based around a highly non-linear (even moreso than in Fallout), interconnected set of narratives. Like Darklands before it and Arcanum a few years later, it’s a game that is occasionally not fun to play but the strong parts are so much more memorable than the bad things that it leaves a great lasting impression.

Fallout 2 is the last oldschool Fallout game. Other games in the series didn’t follow the gameplay style of the original two, with spinoff titles belonging to a variety of genres and mainline titles turning into first-person action RPGs.