Long after the Super Nintendo faded from relevance in America and Europe, the Nintendo Power service ensured its survival in Japan into the 21st century. Part of its success comes from offering a cheaper method of buying games (you’d download them onto a flash cartridge at a special kiosk), but just as much of it comes from the quality of the games it offered. Small though its library might have been, it still contained some of the system’s best titles, whether they were updated rereleases like Famicom Tantei Club: Part II and Metal Slader Glory, or original titles like Fire Emblem: Thracia 776, Power Lode Runner, and Sutte Hakkun.

Famicom Bunko: Hajimari no Mori definitely belongs to the latter category. Released in mid 1999, first impressions would lead you to believe it’s a very humble game. Outside creating Earthbound Beginnings, its developer Pax Softnica isn’t known for creating too much else. Their biggest claims to fame, as they were, were a trilogy of adventure games for the Famicom Disk System, including the two Famicom Mukashi Banashi games, Shin Onigashima and Yuyuki, and Time Twist. However, there’s no evidence showing that Famicom Bunko is connected to these, nor any other series of games. Still, none of this should undercut the level of craft that went into constructing Famicom Bunko. Going beyond surface appearances and the simple summer love story that structures the game, you see a game that makes very poignant commentary about the preservation of the environment and Japan’s cultural traditions, all of it rendered through clever religious imagery and design choices.

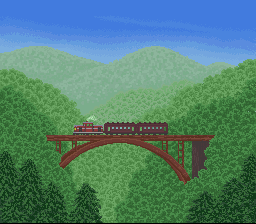

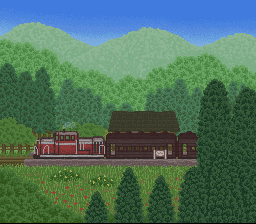

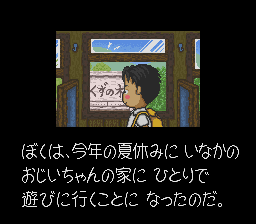

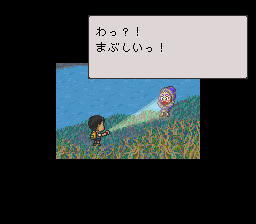

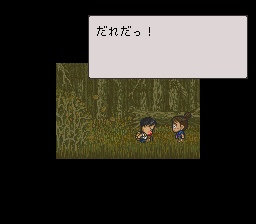

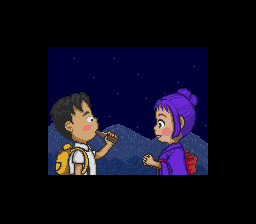

Not that this is what you’re presented with upon starting the game. When you first begin playing, Famicom Bunko looks and plays like an ordinary Japanese adventure game: you spend most of your time selecting actions from a menu at the bottom of the screen, trying to figure out what sequence you need to advance the narrative. And the narrative appears equally conventional. Shortly after stepping off the train and arriving in his grandfather’s rural village (where he’ll be spending his summer vacation), the young protagonist tumbles down a hill and meets a mysterious girl. After that brief encounter with her, he spends the rest of his time in the village trying to reunite with her. Some of the story’s principal actors include:

Characters

Protagonist

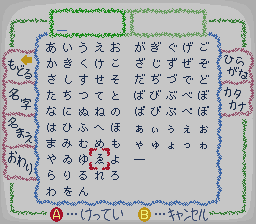

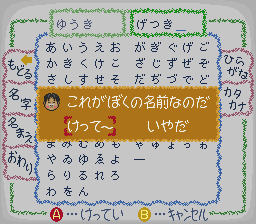

A young boy whom the player gets to name, he basically functions as a stand-in for the player. Unlike a lot of player cyphers, though, this character is very vocal and has a distinct personality of his own.

Komurasaki

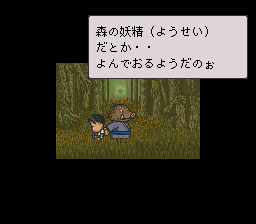

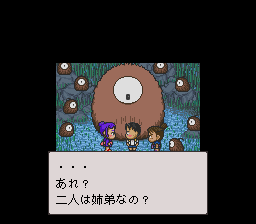

The girl the main character meets at the start of the game, Komurasaki is part of a tribe of youkai called the Ayakashi. She wants to reunite with the main character, too, yet she also has her own goals she works to achieve: restore the forest surrounding her village and keep its people from moving somewhere else.

Kojirou

A friend of Komurasaki’s and a fellow Ayakashi. He’s presented as a vaguely antagonistic character throughout most of the story, yet he ultimately proves to be one of the protagonist’s allies by the end.

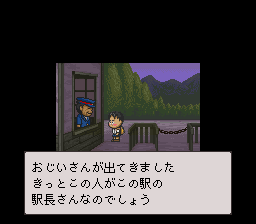

Grandpa

Besides being the main character’s grandpa, he’s also the spitting image of a modern priest: he spends his days riding his scooter around town, fulfilling the people’s spiritual needs. While he’s happy to tell his grandson about the town’s history and its various personalities, he mostly trusts his grandson to his own devices while he attends to his own business.

Neighborhood kids

A group of kids whom the protagonist first meets at a local school. Like Kojirou, they start off antagonistic to him before becoming his friends. Unlike Kojirou, their antagonism is less ambiguous: they tease the main character over minor things, steal his belongings, and express very little interest in being his friend.

Judging by these descriptions, you’d probably characterize the game as a normal slice of life story with a Pocahontas-esque romantic subplot to spice things up. And to their credit, Pax Softnica clearly has the skill necessary to make that angle work. Wandering around the village carries a certain appeal to it. Some of that’s because of the colorful personalities populating it (even beyond those that were just listed), but just as much comes from the variety of activities the village offers. Each day holds something new and exciting for the main character to discover, like helping the adults fish or playing menko with the neighborhood kids. It’s only natural this would spark some innate curiosity in you and make you want to explore and get involved with the world around you. The music only carries those ideas further: the tracks maintain a constant sense of activity with their playful flutes, the laid-back attitude in their strings, and their consistently upbeat tempos. This helps ensure that Famicom Bunko can maintain a youthful enthusiasm in just about any moment.

In some ways, this isn’t that surprising. Famicom Bunko was released in 1999, right around the same time as games like Gokinjo Boukentai, Boku no Natsuyasumi, and Ihatovo Monogatari; similar games that also took great interest in the everyday. (Famicom Bunko and Boku no Natsuyasumi even share the “end each day on a crayon-colored diary entry” motif.)

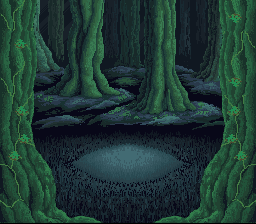

Unlike many of its contemporaries, though, Famicom Bunko has greater ambitions beyond creating a pleasing mood. One of the most frequently recurring pieces of imagery throughout the game is the forest, or in some cases, the lack of one. On his second day in the village, the protagonist’s grandfather tells him the story of Donguri Forest: once the pride of the village, all the trees were cut down for lumber, reducing the forest to a field of stumps. The consequences from that decision were long lasting, maybe even permanent: despite it happening many years prior to the story’s inception, Donguri Forest has yet to grow back. So the game has a clear environmentalist message embedded in its story, but it wouldn’t make that much sense to read it through the lens of industrialization. Instead, given all the religious imagery like fog, forests, and the various mythical creatures populating both, it’s safe to say that Famicom Bunko approaches the topic from a Shinto perspective. More specifically, the game draws on Shinto ideas like respect for nature, interdependence between human and kami, and the idea of completing one’s self through the world surrounding them. By letting their forest fall into such ruin, the people of the village have both lost an important cultural heritage and left themselves with an incomplete existence.

Looking at the town in its current condition, it’s hard not to feel convinced by the game’s arguments. On one level, the townspeople are aware of the gravity of the situation. Remind them of the incident in some way, and a lingering sadness will fill the air as they remember what they’d done as a community and the near impossibility of recovering from that damage. Yet rather than at least try to make amends, the people live in a sort of ignorance, going about their daily business without giving much thought to anything beyond it. Which isn’t to say the game rebukes modern ways of life or anything like that; it’s careful enough to approach the topic with more of a lamenting tone than a moralizing one.

At the same time, though, the game shows enough of awareness to explore just how detrimental the peoples’ focus on their daily business can be. It’s like they live in their own secluded bubbles where time doesn’t move: they’re happy to either stay where they are or cycle through the same set of actions all day, and unless the main character penetrates that bubble and asks them for help, that’s exactly what they’ll do. While this disengaging with the outside world definitely makes their lives easier, it doesn’t help them overcome the original loss of Donguri Forest. If anything, it only lets the problem stagnate further, as they’ve completely sidestepped the issue of actually doing anything about it. Things are getting so bad, in fact, that the Ayakashi themselves are forced to move to another forest whose spiritual power isn’t as faint as the one they’re currently living in.

Conversely, this would also explain why the main character is so valuable to the story. Not only is he able to remind the people about an important aspect of themselves that they’d either forgotten or never took that seriously in the first place (several people think of the Ayakashi as a mere folk tradition), but because he’s the only character who can move freely and advance time forward, he’s also able to bridge the gap between individuals and help them move forward. This hints toward perhaps the game’s greatest strength: the interplay between the story and the way it’s told. Famicom Bunko has all sorts of clever little tricks to ensure content and form play off each other in a meaningful way. Some of them appear in the narrative itself: the story uses parallels between the main story and the old lady’s fairy tale to explore just how valuable the past can be, and then lends the world a sense of intrigue and mystery by filling the main story with a lot of aimless wandering (which somehow leads the protagonist to his current goal).

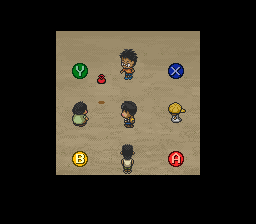

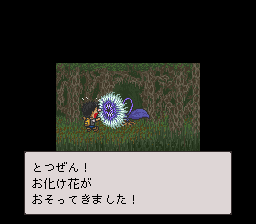

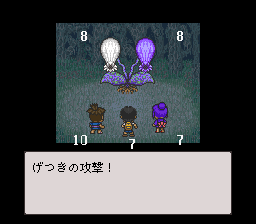

However, many of the game’s more impactful techniques show up during play. Famicom Bunko is a more flexible game than appearances would lead you to believe. Although the game plays like an adventure game for the most part, the story is split up into six days, and each day contains one or two simple mini-games to help break up the action. They act as a nice diversion from the regular gameplay, but these mini-games also let the game achieve a variety of moods it might be able to achieve otherwise. Each one feels like it was fine tuned to get as great an emotional impact in that small window of time as possible, whether it’s the serenity of fishing by the river, the competitive spirit behind a couple of rounds of menko, or that one tense moment where you have to sneak past an angry bulldog Solid Snake style, cardboard box included. (In case you’re wondering: yes, the dog does pee on the box in the end.) The end of the game in particular is crammed full of these memorable moments. Standing out among them are the evocative series of RPG battles against the forest’s creatures as the protagonist makes his way toward the titular Forest of Origins. It’s hard to explain what makes them work without spoiling some major plot developments, though, so it’s best that you experience them for yourself.

Looking back on Famicom Bunko, it’s hard to tell what level of success, if any, the game enjoyed. Being a Nintendo Power release must have limited its availability, and while it later became available on Virtual Console (both for Wii and Wii U), it hasn’t garnered any real attention outside that. It’s a shame, too, because Famicom Bunko is easily one of the strongest games the Nintendo Power service had to offer. The game demonstrates some strong command over its form, knowing what to borrow from other games while setting itself apart with strong themes and intelligent game design. Like many under-appreciated gems, Famicom Bunko‘s the kind of game where after finishing it, you wonder why more people haven’t heard of it already.

Links:

Famicom Bunko Official website, written from the main character’s perspective.