- Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir

- Famicom Detective Club Part II: The Girl Standing in the Back

- BS Detective Club: The Past that Disappeared in the Snow

- Famicom Detective Club (Switch Remakes)

This article covers the original Famicom version. For the Switch remake, please see Part 4 posted later in the week!

In 1985, Yuuji Horii’s murder mystery Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken was ported from its microcomputer origins to the Famicom, where it sold over 700.000 carts and more or less single-handedly popularized and formalized the Japanese adventure game (ADV) genre. In the wake of the Portopia port, ADV games were soon pouring in on the Famicom. Nintendo’s first own attempt at the genre was the 1987 Famicom Mukashi Banashi: Shin Onigashima released on two double-sided disks for the Famicom Disk System (FDS). While popular, the game, which was based on Japanese fairy tales and rather silly in tone, was a far cry from the suspense of Portopia, and for one of their next ADV games, Nintendo set out to create a murder mystery of their own: Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir.

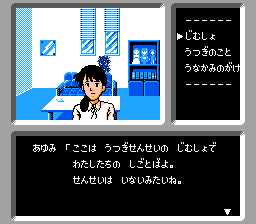

While most murder mystery games at the time featured adult protagonists, Famicom Detective Club was an early example of teenage sleuths in the genre. You play as a 17 year old boy who wakes up on a beach with memory loss, apparently caused by head trauma after falling off a cliff. A local man named Amachi finds you and takes care of you until you have recovered your health. Remembering nothing, you return to the beach and meet a girl named Ayumi Tachibana that has been looking for you. You learn that the two of you work at Utsugi Detective Agency and that you were investigating a potential murder case in a country side village when you suddenly went missing. You also learn that you are an orphan and that Utsugi took you in as his protégée. In typical fashion of the time, the player is then asked to name the protagonist, implying that they should choose their own name to increase the immersion (there is no default option but the character’s unofficial name is Naoya Takada, which was the name used in a Kieta Koukeisha gamebook published by Futabasha). Determined to regain your missing memories, you return to the village where people seem to know you as the detective who is investigating the suspicious circumstances surrounding the death of the matriarch of the Ayashiro clan, one of the wealthiest families in the country. However, as more murders occur, the villagers start to rumor about a curse from the Sengoku-era that if an Ayashiro is killed they will be resurrected from their grave and seek vengeance on all around them…

The game came on two disks released two months apart, but should be seen as one single game, as the second disk can only be started when the player has finished the first. The first disk (Zenpen) is sadly a slow an mostly uneventful affair that focuses mainly on setting up the intricacies and intrigues of the Ayashiro clan and their staff. It is not until the second disk (Kouhen) that the game starts to pick up pace, and this disk does overall feel more polished and has some minor improvements such a few redrawn locations and character sprites, and giving the protagonist a small inventory. There is even a 3D maze at the very end of the game, yet another thing the game copies from Famicom Portopia. The re-released version in the Famicom Mini-series on the Gameboy Advance combines the two disks into a single game (Zengouhen: “first and final parts”). This is probably the best way to play the game since there is a lot of disk swapping and risk of getting disk errors on the FDS version.

The game’s biggest issue, however, is that it is extremely linear even for an ADV game. Most of the time, you cannot roam freely through the world but have to go to scenes and locations that the exact order game has decided for you. This heavily scripted presentation does not lend itself that well for an investigative murder mystery game, but would not feel out of place in a film or novel. In fact, Kieta Koukeisha at times feels like a precursor to the visual novel genre in the way it offers a lot of dialogue and a more limited player interaction than in many of its contemporaneous peers. Sadly, in the instances where the game actually allows you to choose where to go and whom to talk to, the narrative often loses traction and you have to walk around a lot and inquire about the same topics over and over until you trigger flags that let you progress (a common issue found in many ADV games). There are a few subplots, but they aren’t among the game’s strong points. The one regarding the protagonist’s amnesia is interesting on paper and does manage to add some nerve to the first hour or so of the game, but soon begins to muddle the storytelling. It feels like you are retracing your own steps without knowing if anything you find is significant, or is something your character already solved prior to falling off the cliff. Worse, at times the amnesia subplot is almost forgotten (oh, the irony) among the narratively ambitious, but somewhat disjointed intrigues of the Ayashiro household. There is another subplot about looking for your real parents that works slightly better, mainly because it mostly runs orthogonally to the main plot.

The game does not do a great job of explaining how the different villages and cities you visit are geographically related, but the manual features a nicely illustrated map that mitigates this issue.

The music generally sounds great, but the same tracks repeat a lot, and thus sadly end up becoming a nuisance, but the addition of some new, suspenseful tracks in disk two alleviate this to some extent. There is also a little jingle that plays every time when you uncover important facts. At first this does not seem that special, but as the game progresses the positive conditioning from hearing this sound so often does actually help bring your focus back into the game, had your mind started to wander from the sometimes long-winded dialogue. Nevertheless, it is difficult not to compare this game disfavorably to the Famicom port of Yuuji Horii’s Hokkaido Rensa Satsujin: Ohotsuku ni Kiyu which was released in the same year, 1987. Okhotsk has excellent graphics (especially the character sprites) and a pacing that despite having some issues of its own arguably flows better and is less linear than Kieta Koukeisha.

Screenshot comparisons

FDS GBA

FDS GBA

FDS GBA

1988 game book published by Futabasha and origin of the unofficial name of the protagonist (Naoya Takada)

References and further reading

A previous HG101 text on this game has appeared in:

Kalata, K. & Hubbard D. (2017) HG101 Presents: The Complete Guide to the Famicom Disk System

The game was featured on Game Center CX episode 145 (2012), which could be a good place to start for those wanting to watch a subtitled playthrough/commentary.

Interview with Sakamoto regarding the game (among other things):

High quality scans of the manuals. It featured an illustrated introduction to the story and characters, a map, and a “detective journal” in which you could fill out the clues you’ve learned about the different people:

https://www.gamingalexandria.com/wp/2018/10/famicom-tantei-club-kieta-koukeisha-zenpen/

https://www.gamingalexandria.com/wp/2018/10/famicom-tantei-club-kieta-koukeisha-kouhen/

Japanese blog entry about Futabasha’s Kieta Koukeisha game book, with examples of the illustrations within:

https://dafe4345fsfgrghyu.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-116.html

Seishi Yokomizo’s novel The Inugami Family (犬神家の一族, “Inugami-ke no Ichizoku”, 1951) is one of the more well-known cases of one of Japan’s most famous fictional detectives, Kosuke Kindaichi. Despite Sakamoto claiming Dario Argento as his main inspiration, the similarities between the The Inugami Family and Kieta Koukeisha are numerous and thinly veiled: a rich family living in a mansion in a small Japanese village, whose members are in a dispute over a will from the recently deceased family head; a large and complex cast of relatives and their staff; a coveted family treasure that only the true heir will inherit; a curse cast over the family in the past; a number of murders related to the power struggle over the will; a potential heir that has gone missing; an ornate tobacco case that holds a secret; and a particular method of murder that is difficult to detect. The book has been published in English as the The Inugami Curse (Stone Bridge Press, 2007; Pushkin Vertigo, 2020). There are also two Japanese film adaptations from 1976 and 2006, both by director Kon Ichikawa.