Intelligent Systems got its start with programmer Toru Narihiro being tasked with porting games from Nintendo’s Famicom Disk System to the format compatible with the more widely used Nintendo Entertainment System’s for overseas production. Known primarily in the early years for developing software-creation-tools, both hardware and software, Intelligent Systems worked closely with Nintendo R&D1 and developed many games that were functionally hardware tech demos like Wild Gunman, Duck Hunt, and Gyromite. Before long, the effort became an offshoot company that was a branch of Nintendo. The drive to make something in a different direction was held, and so Narihiro along with Satoru Okada, Kenji Nishizawa and Gunpei Yokoi sought to develop a simulation game, and the change in direction for the joint-stock company began with Famicom Wars. The goal was to create a strategy game similar to SystemSoft’s Daisenryaku series, which originated on Japanese PCs, but adapted for the younger, wider audience of the Famicom.

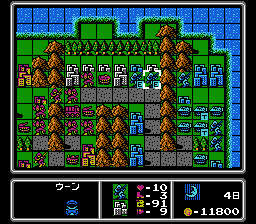

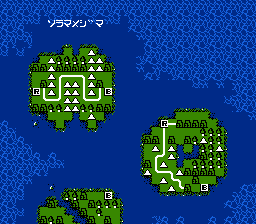

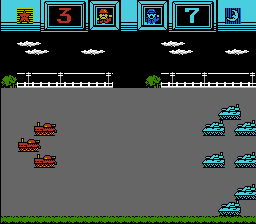

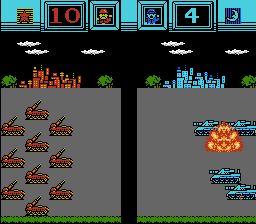

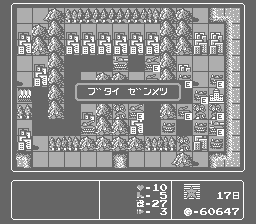

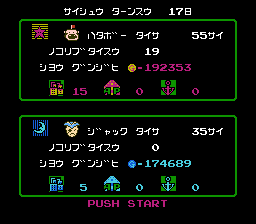

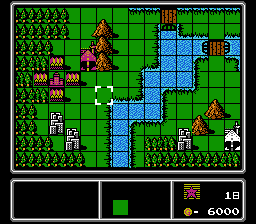

Within Famicom Wars there are two armies, Red Star and Blue Moon. They vie for dominance on a series of non-connected maps for no narratively established reason. These maps are square-grids that host various terrain and structures. To achieve victory, an army must either capture the opponent’s Headquarters (HQ) or destroy all of the opponent’s units which causes a Route. In the pursuit of these efforts, each army will deploy infantry and various modern military war machines, such as tanks, anti-air guns, and self-propelled guns (known through the series as artillery). Red Star and Blue Moon will take turns, with each full round where both armies take a turn being denoted as a day. All units cost funds and must be constructed from appropriate deployment facilities, which in turn can’t construct anything if a unit is occupying its space whether friendly or hostile. Funds are accrued on a day to day basis, the value of which being determined by the total number of properties that the army controls. Only the infantry type units can capture properties that are either neutral or enemy-owned; so while they’re not particularly capable of destruction, they are highly important units for the overall success of the battle.

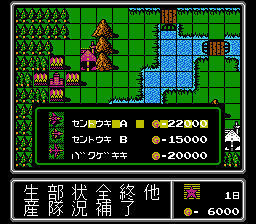

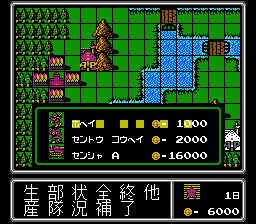

The general flow of gameplay involves the respective armies sending out waves of infantry to take initial properties, and eventually deploying tanks and other units to eliminate the enemy’s units. There are three fundamental unit type: Direct, Indirect, and Support. Direct units roll up next to other units they can engage with on the map and open fire, while Indirects can fire upon relevant enemy targets several squares away at the cost of not being able to move and attack at the same time. Support units consist of transportation units such as armored personnel carriers (APCs), transportation helicopters, and naval landing craft which carry slower units quickly or help land units cross water; there is also the Supply unit which will restore a ground unit’s fuel or ammunition. The transportation units are capable of firing back, leaving them to be a utilitarian ‘middle ground’ option.

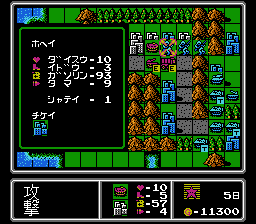

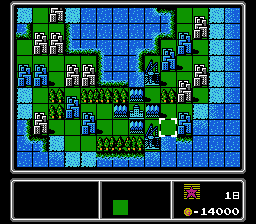

The terrain plays a factor, with more open terrain such as roads or plains leaving units vulnerable while cities or mountains will reduce casualties a distinct amount. A somewhat clever abstraction is that unit health and strength operates on thresholds ranging 1 to 10, with a total unit health consisting of 10 thresholds of 10. So when a unit takes 45 points of damage, they drop from 10 health to 6, but the same damage again would bring it from 6 to 1. When units engage in battle with an enemy unit, each fires a volley at the same time as the other. As a result, it is wise to attempt to use stronger units against weaker ones in direct combat, or utilize indirect units to shell others at a distance. The unit list in Famicom Wars is rather rudimentary, with later installments merging or dividing existing units into new units with more defined roles and adjusted costs.

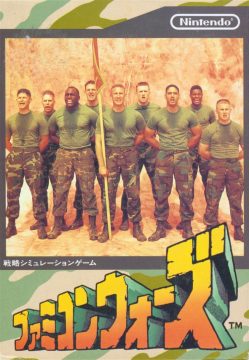

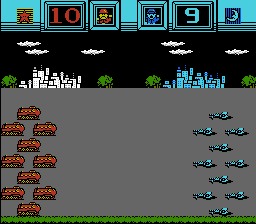

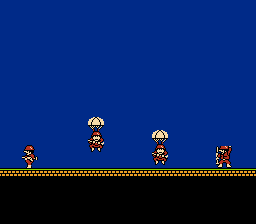

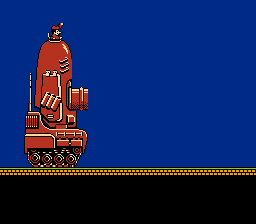

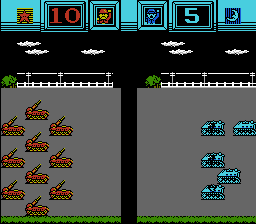

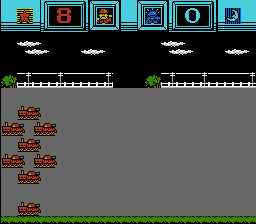

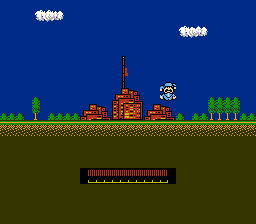

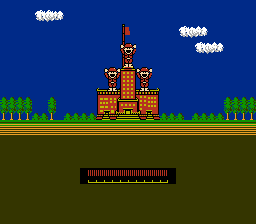

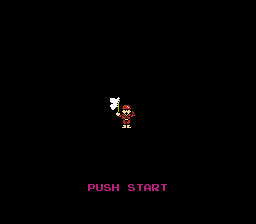

The graphics are a bit difficult to look at, as the palette is stretched a bit thin. They serve their purpose and it’s clear what unit or property belongs to who. One of the more notable aspects of the visuals is that when units engage with each other, the game shifts from a top-down map to a side-by-side scene of the battle unfolding as little cartoony soldiers and war machines are blown away. Similar little vignettes play at other times, including when boarding a transport or capturing a property. There’s even an amusing albeit brief animated introduction as soldiers from the two sides duke it on, only for one side to be scared off by an enormous tank. The audio is functional, though sparse. What tracks there are were composed by the famous Hirokazu ‘Hip’ Tanaka, and carry some similar signatures of his found in Kid Icarus and Metroid.

Overall, the experience is rather clunky. The maps can be a bit large and scroll in slow, tile-wide chunks that take quite a bit to view the entire field. Transportation units will lose their action if another unit boards them, in addition only one unit can disembark at a time in the case of the Lander. There’s little incentive to engage the enemy without having a distinct show of force due to the ‘even trade’ nature of direct combat. The menus are slow, cumbersome. Even moving units is rather arcane as the player is given no indication of where a unit can actually move, short of selecting it and attempting to drag the cursor to an invalid tile in which case it will simply not move. When the AI takes its turn, it has to navigate the menus the same as the player; combined with its need to stop and think about its moves rather frequently, it all only serves to delay things unnecessarily. Most damning of all however is the fact that the maps provide a large number of production facilities early on, with any facilities captured in the middle of the map being incapable of producing units. This results in a lot of front-loaded micro management and it can be a large number of in-game days before first contact with the enemy, this makes game-play rather tedious and prone to stalemate situations.

Famicom Wars was received quite warmly on a critical level upon its release, owed largely to its nature as a simulation and strategy game at a time where finding anything with such depth in a console game format was quite rare. In more recent years, however, it’s difficult to think of it as more than a proof of concept than a genuinely entertaining game. That being said; for a foundational entry one could do far worse, and advancement in development would set the groundwork for making sister-series Fire Emblem a much smoother experience. Famicom Wars would distinguish Intelligent Systems as more than just the tech-team. Narihiro would go on to have a role as either director or producer in all of the series’ successive entries, and provide similar contributions for the Fire Emblem series as well.