When thinking of Japanese RPGs, one will typically think of an anime-styled game like Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest, with linear, story-driven gameplay. This is very different than the typical Western made RPG, where famous games, such as the Fallout series, focus on free roaming adventure and character creation. Nestled somewhere in between these two styles is Squaresoft’s SaGa series. A first glance at the series will immediately bring to mind a typical JRPG, with its anime character designs that look similar to many of Square’s other series, with Final Fantasyobviously springing to mind. However, delving deeper reveals that the series has just as much in common with Western RPGs, with open ended, free roaming exploration being a key element.

The series is the brain-child of Akitoshi Kawazu, who is also responsible for many of Square’s other games noted for an open-ended style of gameplay, such as Legend of Mana for the PlayStation and Final Fantasy: Crystal Chroniclesfor the Gamecube. He has always been known for his experimental style of game design, often trying out new, oftentimes strange, features in his games, and he’s especially known for being the guy behind the oddball Final Fantasy II for the Famicom. This can easily be seen by how different his takes on the popular Mana and Final Fantasy franchises were compared to the main titles in their respective series. His rather avant-garde manner of game design can be seen throughout the SaGa series. And, while certainly not all of his strange ideas wind up being gold, it certainly makes for an interesting experience. Another important person associated with many of the games is composer Kenji Ito. First contributing to the soundtrack of SaGa 2 on the Game Boy, he ended up composing the soundtracks of all but three of the remaining games.

At ten games, plus several remakes, SaGa is one of Squaresoft’s longest running franchises. Yet, it has never reached the level of popularity that many of their other series receive. This is especially true in the United States, where the games are largely unpopular. This is perhaps due largely to its rather Western take on exploration, which may alienate many fans of the more typical JRPG. Perhaps, too, it is due to its often confusing, complicated gameplay features, which are not always fully explained in-game. Certainly, Akitoshi Kawazu’s experimental gameplay features play no small part in alienating its fair share of potential fans as well.

The SaGa series started off as a fairly standard trio of RPGs on the Game Boy. Although these first three games certainly had their fair share of quirks, they still played in a manner that would be immediately familiar to any fan of Japanese RPGs. However, it was with the release of Romancing SaGa on the Super Famicom that the series began to really establish itself as the strange hybrid of Western and Eastern styles that it became known for. Beginning with that game, and continuing in nearly every game that followed, the series largely tossed linearity out the window. Instead, the player is given the whole game world to explore as he likes, with dozens of quests available that he can accept and complete in nearly any order. As a result of this freedom, the series may, at first, seem to be much sparser in plot than most other JRPGs. However, this is not the case. Rather than having a story presented in a specific, linear manner, the player is instead allowed to find, and piece together, story elements by completing various quests. Each game also contains dozens of recruitable characters, scattered throughout the world. The ability to be able to form your personal dream party out of all of the available characters is one of the most pleasurable elements in the series. The freedom the series gives the player allows for multitudes of possibilities. You can attempt the same game with a completely different party, doing the quests in an entirely different order, resulting in a rather different experience. Thus, replay value has always been one of the series’ strongest points.

Further distinguishing itself from other RPGs is the way in which characters develop in SaGa. With the sole exception of SaGa 3 on the Game Boy, the series has never used the typical system of experience points and level ups that most other games in the genre utilize. Instead, character stats will sporadically increase at the conclusion of battle. Although there is an element of randomness to this growth, stats will typically increase as you use related skills in battle. Hence, using magic in combat will often reward you with an increase in intelligence, while attacking with a melee weapon will help increase strength. Equipment, too, has always had a rather unique system, with nearly every game in the series allowing you to equip your party members with multiple weapons at once, allowing you to quickly switch to a variety of attacks in battle with ease.

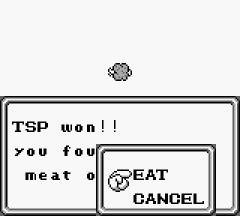

Perhaps the most famous feature of the series, however, is the way in which new special attacks are learned. When attacking in battle, a party member will occasionally have a light bulb appear above their head, and unleash a new attack which, from then on, is permanently acquired. While the likelihood of having this occur is based on the characters’ weapon skill level, there is an element of randomness. So, it can be frustrating when a high level character just can’t seem to learn the attacks you want. On the other hand, there is nothing quite as cool as getting lucky, and learning a powerful attack early in the game. First introduced in Romancing SaGa 2, the name of this feature has been referred to in future games as both “Sparking” and “Glimmering”, and has been used in every SaGa game since.

The series first landed on the shores of the United States with the original installment in 1990. Interestingly enough, however, it was not released here under the SaGa name. Instead, it was renamed after the recently released Final Fantasy. Thus, the trio of SaGa games on the Game Boy is known in America as the “Final Fantasy Legend” trilogy. This has led many people to believe that these three games are merely spinoffs of the popular Final Fantasyfranchise, not realizing that they were, in reality, the beginning of an entirely different series. The Romancing SaGatrilogy, released on the Super Famicom in Japan, never saw release in the United States. However, the series returned to the United States with the launch of SaGa Frontier for the PlayStation, and every game since has also seen release here. Unfortunately, they have remained decidedly unpopular, consistently scoring poor reviews from professional gaming magazines and websites. Ironically, it is the series’ crowning achievement, its open ended gameplay, that is the cause of much of the criticism. Invariably comparing the games to more mainstream titles, reviewers often mistake the lack of linearity for an absence of purpose, inaccurately claiming the games to be devoid of plot. Also a target of criticism is Akitoshi Kawazu’s habit of implementing strange, experimental features in his games, a fact that culminated in the highly experimental, but utterly maligned, Unlimited Saga.

Yet, despite its lack of critical acclaim, SaGa has managed to stay just popular enough to stay alive. Although it is not, and most likely never will, become one of Square’s mainstream series, it has managed to last for over fifteen years, which is certainly no small feat.

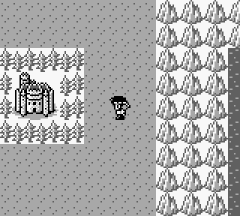

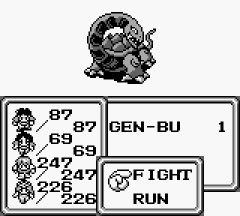

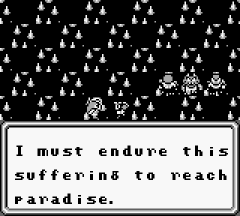

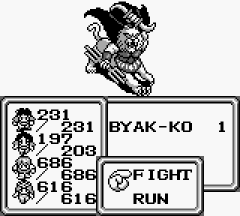

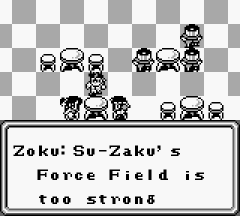

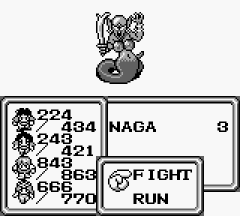

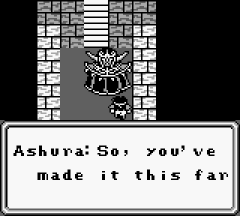

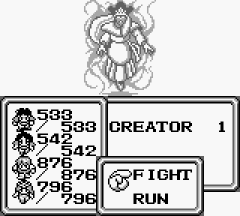

The first game in the series landed on the Game Boy in 1989. It’s a fairly typical JRPG, with a completely linear story and a battle system that looks as if it were taken straight out of Dragon Quest. Perhaps the game’s most interesting feature is its setting. The story focuses on a massive tower that connects to multiple worlds. The different worlds that connect to the tower range from typical fantasy settings to post-apocalyptic wastelands, creating an interesting contrast. The main bad guys are members of the Chinese constellations – Gen-bu the turtle, Sei-ryu the dragon, Byak-ko the tiger, and Su-zaku the bird. These are all lead by Ashura, the Japanese god of war. The game ends with a battle with the “Creator”, which is typically interpreted as taking down the Christian god. (He is called “Kami” in Japan, which means, of course, “God”.)

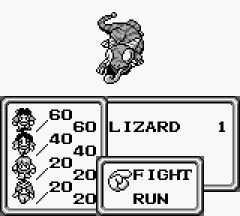

You take the role of an adventurer living in the world that exists at the base of the tower who, along with up to three companions, attempts to take on the tower’s challenges and reach the top, venturing through the different worlds in the process. All of the characters in the party are created by the player, and can be chosen among three classes:

Humans

Humans learn no natural abilities. Instead, they can utilize more equipment than the other two races. Up to eight weapons and pieces of armor can be equipped at one time, making them very versatile in attack and defense. However, they can only develop their traits by buying stat raising potions, making it an expensive procedure to increase their battle prowess.

Mutants

Mutants randomly increase their stats at the end of battle. In addition, they can naturally have up to four special abilities. Unfortunately, these are gained and lost at random, and unless the player saves constantly, they may find themselves having their good skills replaced by useless ones.

Despite its linearity and very basic battle system, it does have certain elements that would eventually develop into the traits that the SaGa series is noted for. Probably the most infamous of these is weapon durability. Unlike most games, where buying a weapon means being able to use it as much as you want, all weapons in Final Fintasy Legend come with a certain number of uses. Every time a particular weapon is used in an attack, its durability decreases, and once it reaches zero, the weapon breaks. This system, or a variation of it, would be used in several of the later SaGa games. Equally important is the way in which characters develop. In this game, experience points are not awarded, nor do the characters have levels. Each of the three character classes develops in a different way, and the way in which Mutants develop is a clear precursor to the system that would become the trademark of the series.

Although it seems rather dated by today’s standards, its quirks still make it a notable game for the system. If nothing else, it’s interesting to see the series in its infancy, when the developers were still experimenting with elements that would eventually become the backbone of the later sequels.

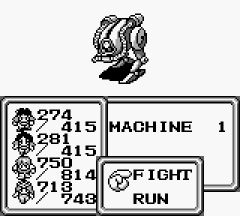

The game was later remade for the WonderSwan Color in 2002. In addition to receiving a substantial graphical facelift, several minor tweaks, taken from the later games, were included that made things a little more convenient. Many bugs were fixed, and you can now go through several events with only one party member (you needed the full roster of four before). Key items are kept in a separate place and are now impossible to get rid of, so you can no longer screw yourself over by discarding an important item. A few names were changed because they were viewed to be potentially infringing: the “Beholder” (from Dungeons and Dragons) became “Death Eye”, the “Nezumi Otoko” and “Nezumi Musume”, both references to Gegege no Kitarou, were changed to “Nezumi Oyaji” and “Nezumi Onna (“Mouse Old Man” and “Mouse Woman”). The “Mobile Suits” enemy was too close to Gundam, so they became “Mobile Machines”. This remake was later ported to cellular phones, with a few minor changes, the most noticeable being the addition of kanji due to the higher resolution display. Both versions of the remake remained only in Japan.

Links:

RPG Land: History of SaGa A brief history of the series.

Moby Games: SaGa Universe Basic information on the individual SaGa games.