- Wasteland

- Wasteland 2

- Wasteland 3

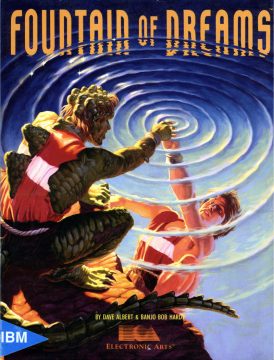

- Fountain of Dreams

- Wasteland in Other Media

Wasteland’s reception came at a time when Electronic Arts was radically altering its business strategy. Its CEO at the time, Trip Hawkins, characterized it as a shift from an elite to a mass market, focusing not on the “esoteric”, but the mainstream. Its back catalogue would be ported to the burgeoning gaming console market, while sequels to its properties would start to be developed in-house.

Such was the case with Wasteland: While it was developed by Interplay, Electronic Arts was the owner of the intellectual property. EA attempted to replicate its success, but without the creative talent behind the original game, its attempts would fall short and only two games would be published before the plug was pulled. Both would use a new engine built from scratch to replicate the feel of the Wasteland engine, but with only a fraction of its functionality – just enough to release them just two years after Wasteland made the waves.

One of these games was Escape from Hell, the off-beat pastiche of conventions that could have been a cult classic, were it not for its subpar gameplay and limited reactivity. The other was Fountain of Dreams.

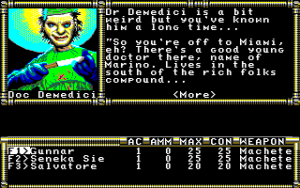

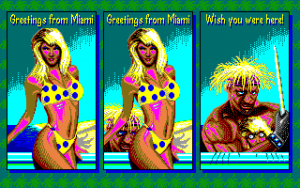

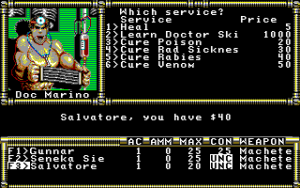

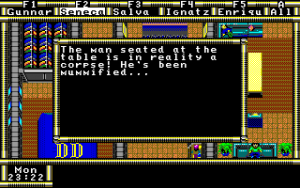

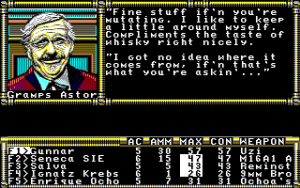

The game is set in post-nuclear Florida, separated from the mainland by seismic shocks unleashed by the nuclear bombing of Georgia. The peninsula itself was attacked with neutron bombs and chemical weapons to remove the human presence and preserve Cape Canaveral and other technology for the subsequent invasion.

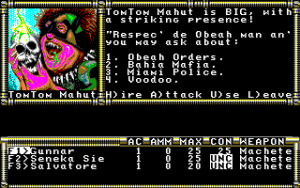

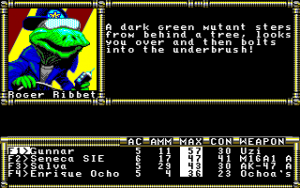

Humans survived and Florida devolved into a patchwork of city states, with the largest of them being Miami. The city took a secondary nuclear salvo, fracturing into a Byzantine web of factions warring for dominance over the city, and kept in check by the ruthless Miami Police Department. Now, half a century after the Change, mutations run rampant in the population, killer clowns lurk in the shadows, and you get plopped right in the center of the quagmire to try and find some sanity in a world gone mad.

The setting outlined in the manual promises a game that could stand up to Wasteland as a worthy follow-up. Unfortunately, the apple has fallen far from the tree, tumbled down the hill, and wound up in the radioactive muck of the sawgrass-infested Everglades.

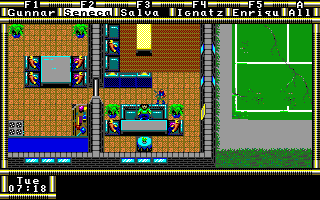

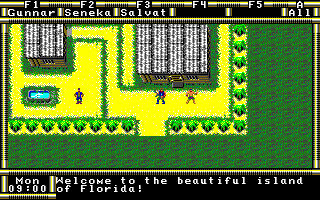

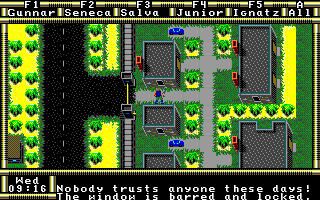

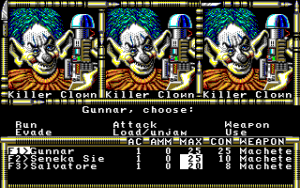

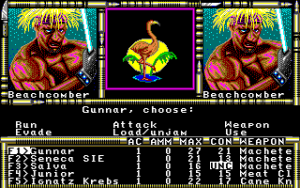

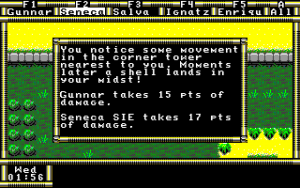

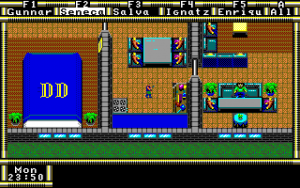

As soon as you enter the world map with your three intrepid Floridians, the game’s limited scope becomes apparent: The patchwork of city states is nowhere to be seen, or even the coastline for that matter. You’re corralled into a small area around Miami by a literal wall surrounding the city. The only other locations are the starting compound that gets wiped out by killer clowns not long after the start of the game, the killer clown base, and the Everglades. They aren’t even a distinct separate map, but a tangle of damaging plants you meander through at random to resolve the main plot and find the titular fountain to save humanity from mutations.

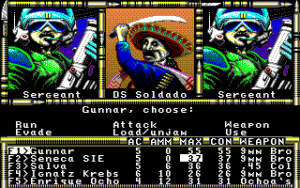

It’s a lofty goal that’s difficult to achieve, thanks to the game’s structure. You’re given very limited information and even less direction. Plot progression occurs in spite of your efforts, rather than thanks to them, as you meander through Miami, slaughtering local cultists, gangsters, and interfering in the affairs of local factions just because you can. Even with one of the few walkthroughs in hand, trying to figure out the next step and then figuring out how to set the correct flags is a challenge.

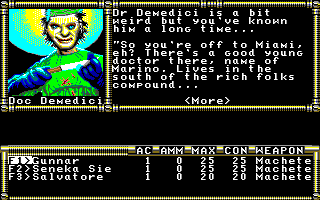

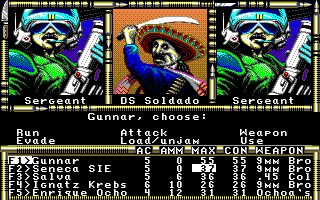

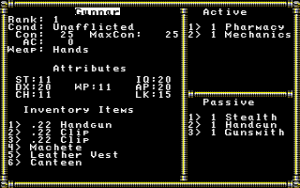

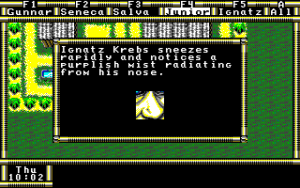

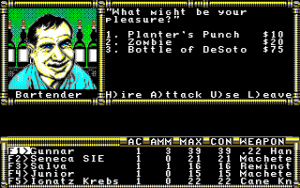

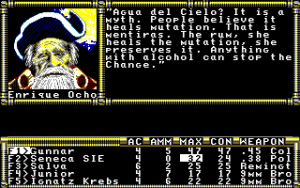

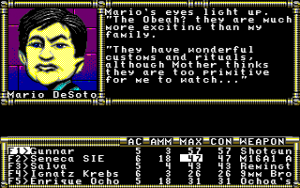

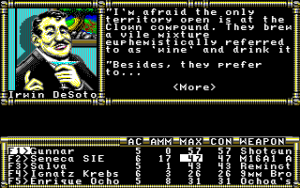

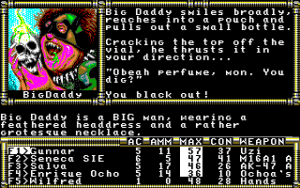

The character system is another matter entirely. The game offers seven attributes (Strength, Intelligence, Dexterity, Will Power, Aptitude, Charisma, and Luck) tied to twenty skills divided into active (such as lockpicking or medical skills) and passive (weapons, perception, and others). Rather than select skills to learn, you pick specific classes for your initial characters. An additional wrinkle provided by the mutation system. As you fight Floridian wildlife, your characters can be exposed to various mutagens that can trigger a limited number of mutations. These are additional skills, in effect, but eventually inhibit healing unless you have a supply of DeSoto rum that can counteract that effect.

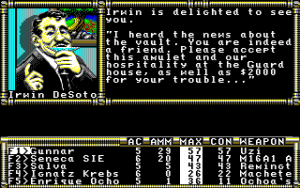

Much of that is rendered meaningless by the game’s structure. Only Intelligence and Aptitude really matter, since they govern how much you can improve your skills through use, while most skills are learned either by paying fees or simply reading books found in the DeSoto compound in Miami. There’s no skill point or attribute requirement. Even without that, the recruitable characters you come across will quickly fill out any gaps in the skill assortment. Even the mutation system is only skin deep: Most don’t provide a concrete benefit and once contracted, they can only be mitigated with the aforementioned rum, turning them into a money sink, rather than a strategic choice.

If you’re willing to stick with the game, put up with the same four types of mutant animals spawning everywhere, mend the fences between the Beachcombers and the OhOhs, make peace between humans and mutants, and wipe out the killer clown menace that someone thought was a good idea to include in the game, you’re treated to a still picture, a text box, and a feeling of wasted time.

There are hints that a game of much greater scope was attempted, one that would do justice to the manual’s description. Commented out skills such as pickpocket, boating, and forgery hint at a greater world. Assets released by Alan Murphy, one of the artists that worked on both Fountain and Escape, indicates that a parody of Disney World was planned, to build on the demented world of the mutated isle of Florida.

Fountain of Dreams was a flop, regarded as, at best, a pale imitation of Wasteland. In the words of the legendary Scorpia, it was a game that captured the form, but not the essence of its forerunner.