Whenever I smell asphalt, I think of Maureen. That’s the last sensation I had before I blacked out; that thick smell of asphalt. And the first thing I saw when I woke up was her face. She said she’d fix my bike. Free. No strings attached. I should’ve known then that things are never that simple. Yeah, when I think of Maureen, I think of two things: asphalt… and trouble. – Opening monologue

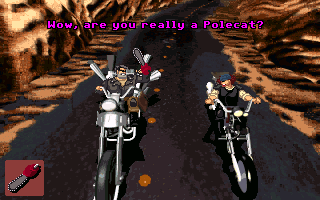

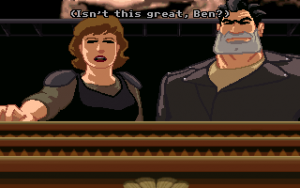

The world of Full Throttle seems to be expansive desert wasteland, filled with dilapidated businesses, scummy bars, and long, open roads. Cars seem powered by hover technology, but that’s the only hint of a futuristic setting. It might seem like a nightmare to a normal person, but it’s the way of life for the Polecats, a group of bikers in this quasi-apocalyptic landscape. Keeping up turbo powered, flame-exhaust-spewing motorcycles is a drain on the wallet, though, leaving the Polecats hard up for cash. They stop at a bar, and, in a stroke of what appears to be luck, they’re contracted as bodyguards for Malcolm Corley, president of Corley Motors, the last company in the country still producing the bikes they love. Despite being a bit old in the tooth, Malcolm is a lively gentleman, filled with stories from his younger glory days, and he’s heralded as something of a hero amongst all the biker gangs. Naturally, the Polecats are enthused.

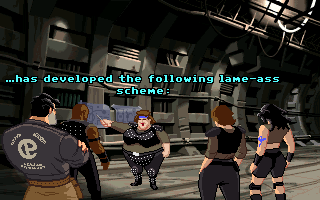

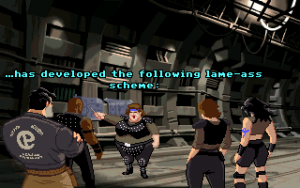

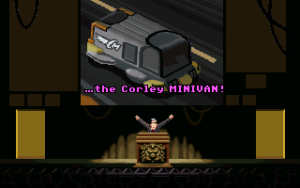

Their leader, Ben, isn’t quite so convinced. He has something of a bad feeling, especially when he meets Adrian Ripburger, vice president of Corley Motors, an all-business corporate suit who cares little for bikers or their culture, but does like to take their money. Before Ben can properly decline, Ripburger and his thugs rough him up and chuck him in the dumpster, convincing the rest of the gang to go along with his plans. Ripburger, it seems, has a devious plot to murder Corley and stage a hostile takeover of the company, turning the product line entirely to minivans. If this weren’t insidious enough, he plans to pin the murder on the Polecats.

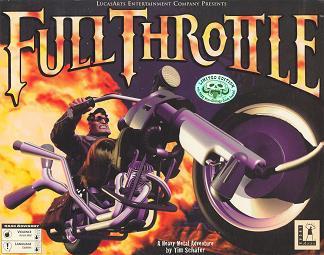

And so begins Full Throttle proper, the first game by soon-to-be-revered developer Tim Schafer. Although Schafer had previously worked on other Lucasarts titles, including Monkey Island 2 and Day of the Tentacle, Full Throttle was his first truly original project. In many ways, it’s a bit different from typical Lucasarts fare, which gained a reputation for silly, light-hearted works like Monkey Island and Sam & Max Hit the Road. While Full Throttle still has something of a cartoony artstyle, the visuals are much darker, the tone much more serious. That’s not to say the game isn’t funny, it’s just that the humor is more subdued.

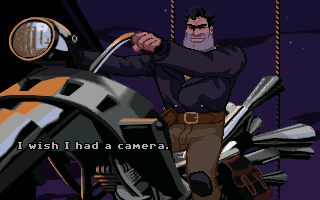

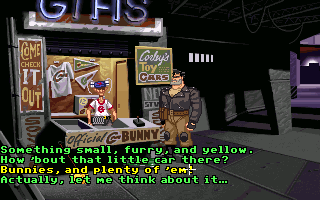

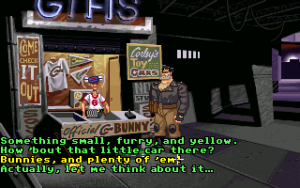

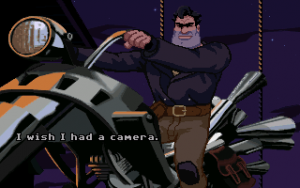

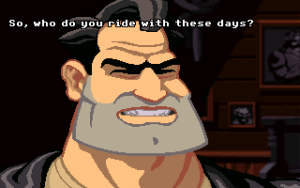

At the center of this is Ben (last name: Throttle, although this isn’t officially stated in the game or manual, due to sensitivities over a similarly named character in the cartoon Biker Mice from Mars, which aired around the same time as the game.) He’s huge, with a 50s superhero-style lantern jaw, a permanent five o’clock shadow, and eyes that appear to be permanently squinting. He’s voiced with a low grumble that somehow manages to convey a bit of emotion without really changing tone. He’s gruff and slightly sarcastic, although some of the laughs come from the contrast of sticking such a manly man in slightly emasculating situations, like stealing a horde of cute, mechanical bunnies to clear a minefield.

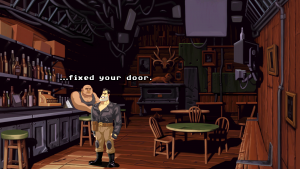

The first time you control Ben, he’s still stuck in that dumpster, left for dead and none too pleased with the thugs who stuck him there. Your first act is to break out of it by punching straight through its lid. You can stick around and kick it, if you’d like (“Take that.” He quips nonchalantly. “And that.”) You’re unable to start your bike (“Some joker took my keys.” Ben states, slightly irritated. “I don’t like that.”) so the first step is to get back inside the bar. The door, of course, is conveniently stuck, but that’s nothing a quick boot won’t fix. The bartender will claim ignorance, although he’ll talk quickly when you grab his nose ring and slam him into the table. (“You know what might look better on your nose? The bar.”)

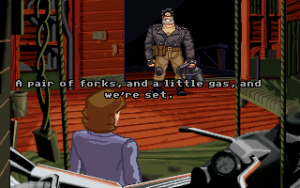

Ben drives away but finds his bike has been tampered with, causing him to crash and once again finding him unconscious. This time he wakes up in the company of a mysterious woman who calls herself Mo (short for Maureen), who seems to know a whole lot about motorcycles. Ben doesn’t quite know it just yet, but Mo is the lost daughter of Malcolm Corley, and she plays an important role in putting a wrench in Ripburger’s plans. But before they can do that, Ben needs to search the local town for tools, all of which involve breaking and entering in some capacity.

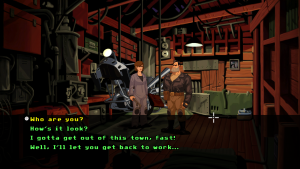

These two introduction sections set the tone for the entire game of Full Throttle. Like any point and click adventure, there are puzzles, but many of them revolve around simple (and occasionally clever) use of force. This obviously suits Ben’s demeanor, as he’s more of a “beat up dudes, don’t bother asking questions” sort of guy anyway. It uses an advanced version of the SCUMM engine which technically ditches icons altogether. Instead, when the mouse hovers above something you can interact with, it turns red. Hold down the mouse button and a board pops up, allowing you to look at, interact with, talk to, or kick whatever you’ve highlighted. The board itself is appropriately themed, with a blazing skull and painted flames. The right mouse button will bring up the inventory, although you don’t really use it all that often.

Some of the puzzles are a bit more action-focused, especially right at the end, where you need to think (and act) quickly under a strict time limit. You can, technically, die, but the game immediately starts over the segment from the beginning, so there’s no need to save constantly, keeping alive another hallmark of Lucasarts gaming, while still throwing in a sense of danger and excitement that’s usually missing.

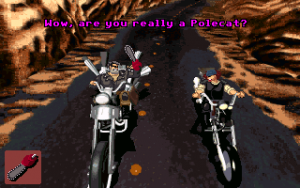

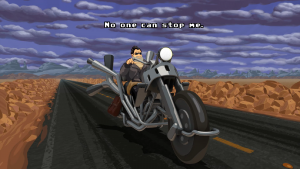

About halfway through the game, you can control Ben’s bike directly as you speed along the highway. The visuals are displayed with sprites over looping full motion video, probably using the same technology as Rebel Assault. Thought it looks nice, in reality, there’s not much control here, because there only a few locations at opposite ends of a straight line. You can, however, exit on to Mine Rd. for some combat. In order to get a few vital items, you need to defeat various members of opposing bike gangs. Although you start off with a mere tire iron, beating up thugs eventually awards you with better torture devices like maces, chains, 2x4s, and chainsaws.

In some ways, these sections are pretty gratifying, because controlling a bike simply by pointing and clicking completely removes the visceral feel of flying down the road. Alas, adventure games have never been known for their quality action segments, no matter how hard they try, and unfortunately Full Throttle is no different. The bike-to-bike fighting is sluggish and awkward at best, and frustrating at worst. Most of the time, victory depends on choosing the right weapon and bashing away, although the battles that necessitate some skills – like grabbing a pair of goggles from a biker still in motion – requires steady driving and some vaguely abstract sense of timing. You don’t get to choose your battles, either, you simply come across bikers randomly, and you may need to fight several pointless battles until you happen upon the one you want. (There is a way to cheat by hitting Shift-V to win any bike fight, at least.) There’s also another segment where you control a car in a destruction derby. This section isn’t really focused on reflexes or even action, although it’s an interesting device for puzzle solving, even if the controls are still pretty irritating.

The shift away from abstract puzzle solving and more towards action was definitely a conscious choice. Although Lucasarts had produced several CD-ROM games, most of them were identical to their disk releases, only adding in voiced dialogue. Full Throttle is their first game that really puts the medium to use, with tons and tons of cutscenes for a full cinematic experience. They wanted something that anyone could see to the end, without getting stuck up on mindbenders with obtuse solutions.

Still, the problem faced by Full Throttle is the same one faced by Japanese RPGs when they got too cinematic – it’s a bit focused too much on story-telling and not enough on interaction. It’s also startlingly linear, especially compared to the freeform design of other Lucasarts games, and it’s remarkably short. Even without a guide, anyone can probably see the whole game in less than five hours. Still, it’s an amazing experience while it lasts, and doesn’t feel over bloated by unnecessary subplots or tacked-on puzzles.

At least it looks fantastic, even years after its release. Instead of using compressed FMV like many games of the time, Full Throttle pulls off most of its animation using the in-game engine, looking much like the intro scenes from Day of the Tentacle and Sam & Max Hit the Road. Much like these, it runs in 320×200 256-color VGA, using lots of flat coloring and pixellated black outlines. Despite its quaintness, there’s a certain unique charm to the style – as much as The Curse of Monkey Island, released two years later and running in 640×480 SVGA, might be superior on a purely technical level, there’s something amazing about seeing beautifully pixel drawn artwork, drawn so huge and animated so smoothly. The full motion video backgrounds of the scenery, however, are heavily compressed, and the artifacting is definitely noticeable, although it’s used sparingly and doesn’t detract too much overall. It sounds fantastic too, featuring at least a few vocal tracks from a “real” biker gang called “The Gone Jackals”. It fits perfectly, and the handful of other instrumental tracks provide more than adequate ambiance.

The voice acting is also uniformly excellent. Roy Conrad completely defines badass as Ben, while Mark Hamill does a lovably slithering Ripburger. Even the minor characters have recognizable voices – the leader of the Vultures is played by Tress MacNelle, using the same voice she later used for the evil character Mom in Futurama, and Maurice LaMarche, famous for his Orson Welles impersonation (and the voice of The Brain from Pinky and the Brain), supplies the voice of Nestor, one of Ripburger’s henchmen.

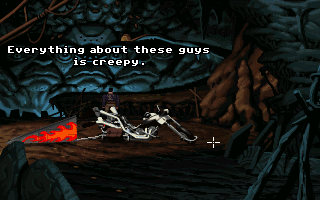

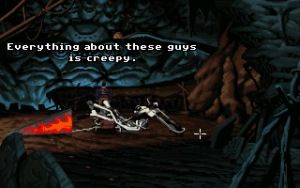

So even though it’s over way too soon, Full Throttle has earned itself the title of an adventure gaming classic. Schafer’s strengths don’t always lie in the dialogue like many other adventures, but rather in the world he creates. Although not quite as fleshed out as the Day of the Dead-themed afterlife in Grim Fandango, or the psychic training camp of Psychonauts, two of his later games, Full Throttle largely succeeds he creates a unique world that works on its own interior rules while still being relatable. Like the rock and roll soundtrack suggests, there’s a universal theme of rebellion, especially against heartless corporations, which can resonate deeply even if you couldn’t care less about Harleys or real life biker culture. The background story is also remarkably deep, especially the cultures given to the rival biker gangs. The Rottwheelers consists of a bunch of stupid but tough thugs, the Vultures are all about snark and speed, while the creepy Cavefish – wearing goggles and clad almost entirely in mummy-like bandages – view their way of life as something of a religion. These are barely touched upon in the game, and there certainly would’ve been room for expansion, had a follow-up ever come to fruition.

There were actually two different attempts to create a sequel to Full Throttle. The first, beginning around 1999, was Full Throttle: Payback, to be helmed by Larry Ahern, one of the artists from the original game and one of the project leads from The Curse of Monkey Island. From day one there appeared to be management issues – Tim Schaefer, the man behind the original game, was not asked to be part of the development team, effectively distancing himself from him and his baby. Other issues from the higher-ups also caused development to stall during the conceptual stage, and thus, it didn’t make it very far off the ground. All that exists are some concept sketches. The plot was to involve Ben attempting to stop an assassination attempt on Father Torque, the former leader of the Polecats, while taking down an evil governor who was in cahoots with Ripburger.

The second game, Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels, was announced in 2003 for the PC, PlayStation 2 and Xbox. The project lead was Sean Clark who, unlike Larry Ahern, had not worked on the original Full Throttle. Rather than an adventure game, it was supposed to be more focused on action. The game’s press release makes mention of 35 different “levels”, which makes it sound quite a bit divorced from the original structure. It also mentions it having over 40 weapons, further emphasizing its focus on combat. The plot involved Ben teaming up with Maureen and Father Torque to take down the Hound Dogs, a new rival gang. It got much further into development, even appearing as a hands-on demo at E3 2003. The reason for its cancellation is much less nebulous than its predecessor – the game simply wasn’t shaping up to be very good, and Lucasarts just figured to cut its losses early on. Given that the abandonment of point and click elements messed up Kings Quest: Mask of Eternity, and further damned both Leisure Suit Larry: Magna Cum Laude and Box Office Bust, maybe it was for the best.

Links:

The Rise and Fall of Full Throttle Includes interview excerpts about the cancelled games.

Adventure Gamers – Full Throttle A review of the game.

Screenshot Comparisons