Licensed games will always leave gamers skeptical. After all, why trust what is essentially a marketing process? That’s especially true for those of us who have grown up during the ’90s. That era’s bargain bins were overflowing with mediocre adaptions and even M&M’s or Barbie ad games. Of course, a whole lot of licensed games are actually very good production.

Now, that’s about how it happened in the West. So, what about Japan? After all, most of its licensed video game products are adapted from manga or anime series. There are exceptions: Capcom’s adaptation of the 1989 horror film Sweet Home for the Famicom ended up being celebrated as a fore-runner of the survival-horror genre, and the first episode of the Nintendo DS series inspired by the famous Game Center CX TV show was even localized in the US. And then, when these licensed titles aren’t based off any manga or anime, the results can certainly be intriguing. After all, the creator of the Mother series, Shigesato Itoi, has his own fishing game; heck, there’s even a Mameshiba title that was released on the 3DS! But let’s go back in the ’90s with Tetsuya Komuro’s Gaball Screen.

The name of “Tetsuya Komuro” may not ring any bells, but he’s actually one of the most succesful pop music producers of the ’90s. Albums he has worked on adds up to 70 millions sales in Japan alone, and he’s often credited for introducing dance music in the Japanese mainstream, shaping post-2000 J-pop in the process. He’s collaborated with countless artists, from Western boy bands and Japanese idols to such legends as Jean-Michel Jarre, Nile Rodgers or Ryuichi Sakamoto. He is part of different acts such as the electro-dance band globe, as well as the synthpop group TM Network and the trance trio Gaball. Quite a career indeed.

It also happens that he decided to produce a video game when he was at the peak of his success, in 1996. The title was developed by an obscure studio called System Sacom that disappeared two years later. It was published by a Sony-owned record label called Antinos Records,which had only published pop idols singles on the system so far. Yup, singles, not games, but considering the imminent halt these “non-games” would come to, it probably wasn’t all that successful. Don’t worry, though – Gaball Screen clearly is a real game. Well, sort of.

The game opens on a cutscene featuring Komuro himself, composing with his large synthesizer in his awful ’90s CG hi-tech living room. He then suddenly stops playing his keyboard and opens a present box whose content reveals itself to be a pair of sports shoes, and just puts them aside on his sofa. Okay? He then decides to get up and score a three-pointer with his baske ball because, yeah, he has a basketball backboard in his living room and he does whatever the hell he wants to. Eventually, he just takes his briefcase and leaves. And you won’t see him again for the rest of the adventure! That’s right – he’s not even the hero of his own game. But let’s get back to that present box we mentioned earlier. Just after the door closes behind Komuro, one of the two shoes starts glowing and finally comes to life, for some reason. That thing then starts fooling around with Komuro’s synthesizer, and it obviously ends badly. There is a short circuit or something and the whole thing has CDs bursting out. The sheepish shoe thus decides to amend his wrongdoings by chasing these stray CDs and get them all back by travelling between the different virtual worlds inside the synthesizer.

Makes perfect sense.

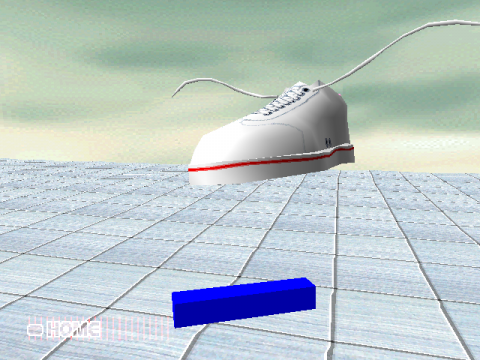

So yeah, you control a shoe. But not just any shoe – a flying shoe. You start in Komuro’s living room, but there’s nothing to do here – apart from scoring a three-pointer like your master – and the only thing you have left to do is dash toward the synthesizer’s screen like in the intro. Once inside the instrument, you get to a menu that is actually a playlist of tracks produced by Komuro, seven in total. Each of these tracks is connected to a set of specific universes, but you can freely choose the order in which you complete them and leave anytime you want to get back to the menu.

Once you have selected a track, you’re thrown in one of those universes. They’re basically rather small game areas with different themes (beach, kitchen, stadium, etc) in which a bunch of different items, decorations or characters with which you can interact lie around. Some will just answer with a purely cosmetic gimmick, but some are vital to your progression. And since your goal is to find all these CDs, what you’ll have to do is interact with as many elements as possible in the hope of uncovering them. Some will simply give you the CD downright, but some others will require you to solve a (very simplistic) riddle. The gameplay remains extremly stripped down overall, and the core idea is just to make the player interact with whatever crosses his path and let him see what happens; it’s about exploring different universes rather than being a challenge of any kind.

Every universe inside a track has a specific number of CDs hidden in its vicinity, and you can only access the next one by uncovering all of these. When you set foot in a universe, an indicator in the upper-right corner of the screen will indicate how many CDs are to be found in the area. You’ll have to find them all in one go in order to keep them. Well, “in one go” may seem a bit of a strong expression, as most universes will only require a few minutes to be completely explored. But these CDs aren’t just a bunch of artifacts you have to collect to progress!

Each CD represents an instrument of the track you’re “in”, and the background music is gradually restored as you find them back. Once you’ve uncovered all five CDs that are scattered around the universes, you’re rewarded with a music video. When a track has been completed, the button that was used to let you into the universes is replaced with one that allow you to watch a music video of said track, in studio quality and featuring vocals. And when you’ve unlocked them all, you even gain access to a bonus clip. It should be especially noted that these music videos are from the ’90s. It’s true they have their own campy charm, but only as long as you watch it from far away.

However, even though the game is definitely a low-cost production, it’s kind of fun to roam around in. Its universes are all diverse, colorful, sweet and rather crazy. You are going through a world where shoes can come to life, fly in the air and score three-pointers after all. The result, with its downgraded yet charmingly weird appearance, looks like a mix between WarioWare and LSD: Dream Emulator. In this surrealist virtuality, you’ll go shopping through a paper-made Paris, ride a soap around a bathroom inhabited by a giant octopus and even scratch breakbeats in a run-down American suburb populated by hip-hop aliens. That’s the whole game’s point of interest, in the end: Simply being a shoe and flying around these absurd worlds in Komuro’s synthesizer is more fun than looking at cheesy music videos, but the music is definitely a part of Gaball Screen‘s atmosphere.

Now, don’t expect avant-garde stuff. Komuro is an important figure of modern electronic music, it’s true, but he mainly produced accessible tracks for the mainstream public. What you’ll hear in this game is the kind of stuff that was broadcast on TV or the radio and was all the rage in clubs back then: dance-pop, contemporary R&B and even eurodisco. In other words, it’s all “easy listening” material. And while it does sound flashy, it’s a perfect addition to the game’s ambiance as it gives it a strangely fitting mushy and hip feel. It’s so cheesy, you can almost smell it through the screen. Here goes the playlist :

SHUBI-DUBI, DUBI-DUBA featuring Yukie Nakama

Yume no Tsuzuki featuring the NO! Galers

CRY-MAX featuring Rina Chinen

….I’m not in love featuring Chie Iwashita

DO I, DO IT featuring the B☆KOOL

waiting for… featuring Ryoko Shinohara

discovery featuring Takashi Utsunomiya

detour featuring Utsunomiya again, along Naoto Kine and Tetsuya Komuro himself.

In the end, it’s a bit hard to judge Gaball Screen. Sure, it’s a (strange) marketing stunt, but if you try to put yourself in the shoes of the developers that were commissioned with such a project, you actually start realizing how cool it is that they managed to turn that thing into a playable LSD-like oddball.