- Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers

- Beast Within, The: A Gabriel Knight Mystery

- Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned

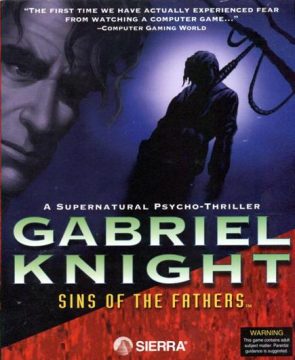

As computer gaming ages, there’s a growing call for the medium to mature, to tell more adult stories beyond the pulp fantasies of a vast majority of games. Many graphic adventure games from the likes of Sierra or LucasArts, while enjoyable, erred more on the cartoonish side, telling light and humorous stories. For a long time, Sierra’s sole “mature” series was Police Quest, although that was of little interest to anyone who didn’t care for crime drama, and it frequently fell into goofiness anyway, despite its best efforts. In 1994, Sierra introduced Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, in an attempt to take adventure gaming to a new level.

Gabriel Knight is the creation of Jane Jensen, an aspiring author who eventually became an actual author after the death of golden age Sierra (officially bookended with the release of Gabriel Knight 3 in 1999). Working her way through the ranks, she eventually assisted Roberta Williams with the story in King’s Quest VI, which is largely regarded as the reason why that entry is so remarkably better than the rest of the series. Given the chance to write and direct her own game, she created one of the deepest and most adult computer games ever developed.

Gabriel Knight is the titular star of the series, an American author turned demon hunter. It neatly straddles the line somewhere between mystery and horror genres – its closest literary comparison would probably be Stephen King, but even that arguably sells the games short. He and his partner, Grace Nakamura, investigate a series of crimes, each heavily entwining historical fact with mythological fiction.

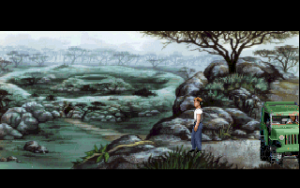

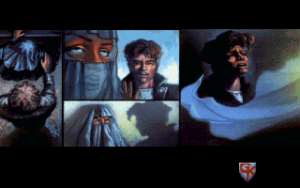

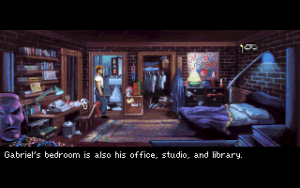

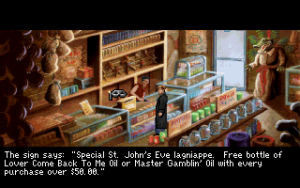

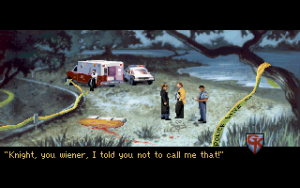

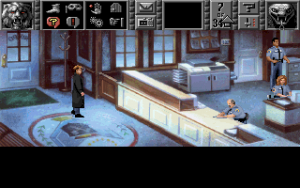

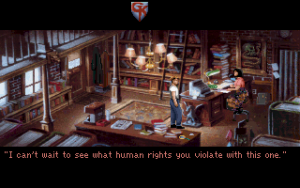

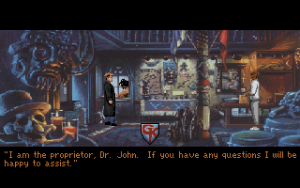

There are three games in the series, each radically different from a technological standpoint. The first game is like most Sierra games – 2D, VGA graphics, with an icon-based parser – and covers Gabriel’s investigations into several voodoo-related murders in New Orleans, as well as his own family’s secret past. This one received the benefit of a full remake for its 20th anniversary. The second game heavily utilizes digitized photography and full motion video using live actors, and takes place in Germany, as Gabriel hunts down an apparent herd of werewolves. The third game is entirely 3D using polygonal graphics, and takes place in a small chateau in France, where Gabriel solves a mystery regarding vampires and the Holy Grail.

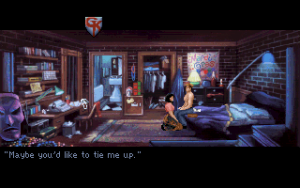

Gabriel Knight, our hero, is a New Orleans native. He’s smart and handsome, but also a bit of an arrogant jerk, and a huge slacker to boot. His few novels have failed, and he resorts to living in the backroom of his New Orleans book store, St. George’s, which also isn’t exactly raking in the dough. His assistant is the lovely Grace Nakamura, the sole employee of his sad little book store. She’s repelled by his chauvinistic mannerisms – the word she uses to describe him is “lout” – but she finds herself subtly attracted to him nonetheless.

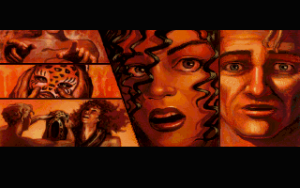

Sins of the Fathers begins with a nightmare – images of spilled blood on a ritual dagger, and a woman burnt at the stake, culminating in a foreboding image of Gabriel’s own limp body hung on a tree. This dream, actually a vision of his distant ancestor, is explained further in the included graphic novel. Waking up in a cold sweat, Gabriel stumbles up out of bed to face the world. Upon reading the newspaper, he learns of a series of “voodoo murders”, ritualistic killings that appear to have an association with the voodoo religion. The experts dismiss this as crockery, but Gabriel sees it as opportunity to get some inspiration for his next novel and sets off to investigate. He just happens to have an in – Detective Mosely, his old childhood buddy, has been assigned to the case, and allows Gabriel access to the crime scene in exchange for a place in his book. What begins as a casual curiosity soon explodes into not only an expose on the underground voodoo cults of Louisiana, but also an exploration of Gabriel’s long forgotten – and cursed – family history. He soon becomes involved with Malia Gedde, a wealthy socialite with deep ties of the history of New Orleans, an affair which brings him closer to both his past and the mystery. He is also pestered by the constant messages from a German who identifies himself as Wolfgang Ritter. Gabriel eventually flies to Europe to meet him, where he learns that he’s the last in a long line of Schattenjägers, demon hunters from the days of yore. From there, Gabriel must not only solve the murders, but meet his ancient destiny, and stop the nightmares that have plagued his family for generations.

Characters

Gabriel Knight

Gabriel Knight, our hero, is a New Orleans native. He’s smart and handsome, but also a bit of an arrogant jerk, and a huge slacker to boot. His few novels have failed, and he resorts to living in the backroom of his New Orleans book store, St. George’s, which also isn’t exactly raking in the dough. Voiced by Tim Curry.

Grace Nakamura

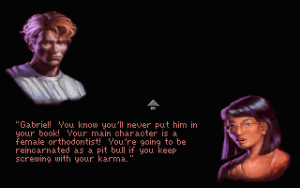

Gabriel’s assistant is the lovely Grace Nakamura, the sole employee of his sad little book store. She’s repelled by his chauvinistic mannerisms – the word she uses to describe him is “lout” – but their sexual tension is undeniable. When not chastising him, she does research for his various investigations. Voiced by Leah Remini.

Detective Franklin Mosely

Gabriel’s childhood buddy, Mosely is a detective at the New Orleans Police Department, who has been assigned to the Voodo Murders case, and allows Gabriel access to the crime scene in exchange for a place in his book. Voiced by Mark Hamill.

Malia Gedde

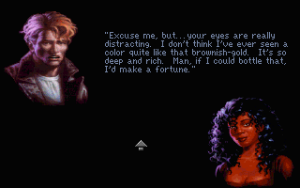

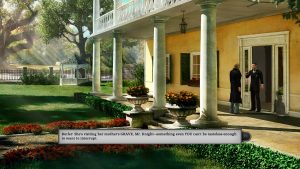

A wealthy socialite with deep ties to the history of New Orleans. Although initially repelled by Gabriel’s advances, she eventually succumbs to her desires and begins some nighttime visits. Her unfortunate involvement in the case eventually causes Gabriel to open his eyes to reality. Voiced by Leilani Jones.

Wolfgang Ritter

Gabriel’s long lost relative from Germany, who eventually enlightens our hero on his family history. He lives in Schloss Ritter, a castle in Rittersburg, Germany, which Gabriel eventually visits. Voiced by Efrem Zimbalist Jr.

The game is divided into ten “days”, each day beginning with Gabriel getting a cup of coffee and reading the newspaper, keeping up on current events. From there, you can access a map to ride around New Orleans including the famous French Quarter and Jackson Square, and the surrounding areas, including Tulane University and Bayou St. John.

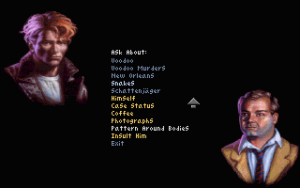

The interface utilizes more icons than the standard Sierra game – in addition to “walk” and “look”, the standard “use” icon has been broken down to “push” and “operate”. You can also choose to “talk” to people for brief dialogues, or “interrogate” for more in depth questioning. In some ways, the extra verbs make it feel like an earlier LucasArts game, but all it really does isthings. The screen view is letterboxed, with the icon bar appearing at the top of the screen, and the dialogue on the bottom. Not only does this lend to the movie-like feel, but it also prevents the text from blocking the visuals.

The writing is almost uniformly excellent – with the occasional slightly silly line – bolstered by some excellent voice work found in the CD-ROM version. Tim Curry provides the voice of Gabriel, which is a love-it-or-hate-it ordeal – it’s distinct, to be certain, but there’s still something off about a British actor trying to do an American Southern accent. Leah Remini plays Grace with an appropriate amount of sarcasm that makes her amusing without coming off as caustic, and Mark Hamill does a less overdone Southern accent as the voice of Mosely. The narrator is played by Virginia Capers, an elderly African-American woman with a very thick New Orleans drawl. She adds plenty of color, but she also talks really slowly, to the point where it’s better to enable text and click through the descriptions.

There are a number of reasons why Gabriel Knight stands out amongst its peers. For starters, its approach to storytelling is much more mature than practically any other game out there, adventure or otherwise. It’s more than just violence, sex and profanity – there’s plenty of that, although it’s rarely too explicit. Simply, Gabriel Knight’s writing and characterizations are head and shoulders above most other adventure games. In most Sierra games, you just click the “talk” icon on someone and exchange a bit of dialogue. In Gabriel Knight, these are far more fleshed out. They take place on an entirely different screen, on a black background, with portraits lip-synched with the spoken dialogue. You can ask any of these people about any of the important topics regarding your investigation. Most of them are in some way relevant to the mystery, but the last option with any character is simply to ask them about themselves. Assuming you’re talking to someone who’s willing to open up, here they will go into huge detail about their background, their likes and dislikes, and other tidbits about their personality. It makes every other character in every other adventure game look like nothing more than a cardboard cutout.

Gabriel, too, is given a far deeper background than your average protagonist. In this game, you can visit your aging grandmother, and have lengthy discussions about your family history, how your grandparents (and parents) met and fell in love, their immigration into America, their life ambitions. You can talk to Mosely, who’s gone from Gabriel’s childhood buddy to a detective with the New Orleans police, and either chat about the case or simply reminisce about old times. You can even exchange playful insults, if you want, which highlights the boyish nature of their relationship. You rarely see depths plumbed this deeply in any kind of interactive narrative.

It also highlights some of the contrasts between video game narratives and literary narratives. During the course of the game’s ten days, you spend about seven of them simply wandering around New Orleans, interrogating people, following up on leads, conducting research, and generally just uncovering background info. It’s not until the seventh day – roughly 3/4 through the game – that you actually leave New Orleans for a quick jaunt through Gabriel’s ancestral home in Germany, before leaving for a tomb in Africa, and then finally returning home for the final encounter. In other words, it takes a sizable chunk the game in order for the “adventure” to truly begin. As the story progresses, it also introduces more supernatural elements, although like Indiana Jones, they’re saved for the climatic scenes. It might feel a bit slow paced at first, but all of this backstory is necessary for the final stages of the game, and make the payoff all the more satisfying.

Where the characterizations really pay off is right at the very end, where you’re presented with a very clear “good ending/bad ending” choice. Suffice to say, the bad ending is… pretty bad, where the surviving characters mourn the departed ones. During the course of the game, death scenes are rare, but when they do happen, they’re really gory – a quick run-in with a mummy results in Gabriel’s heart being torn from his chest. It’s shocking, but perhaps required by something that would call itself a “horror” game. So many adventure games, especially Sierra’s, have prided themselves on haphazardly killing the player characters, for the sake of humor or frustration. Here, it’s legitimately emotional, and even a bit heartbreaking. And that’s when you know that Jensen has done a damn good job.

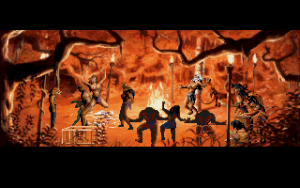

It’s also clear that Jensen is pretty astounded behind the history of voodoo, particularly the brand that originated in Louisiana. New Orleans voodoo is a mixture of African traditions and Catholicism, which sprung up due to the slave trade in the South in the 1800s. Much time is spent exploring the history of voodoo, its misconceptions, and most importantly, how real voodoo has nothing to do with the ritualistic murders being committed in game. It’s pretty educational, and this depth of knowledge largely characterizes the Gabriel Knight series.

The structure does lead to some irritating problems when it comes to progression. Each day will end once certain events are accomplished, and oftentimes you find yourself running around in circles until you stumble upon the trigger that allows the game to continue. Compared to some other Sierra games, though, Gabriel Knight is much friendlier. While the puzzles can be difficult, they’re rarely too illogical. Some of them are typical adventure scenarios, like distracting police offers with a doughnut cart. Others involve interpreting drum codes (which is pretty easy) and translating a symbolic language (which isn’t). Since the game won’t progress unless you solve all the necessary puzzles, there’s really no way to get stuck, not counting a few instances if you save in a stupid place at the end of the game. In other words, it’s pretty progressive, as far as adventure games go.

The soundtrack was provided by Robert Holmes, and it’s one of the best heard in a Sierra title. The song most often heard is Gabriel’s theme, done as a dramatic orchestration on the title theme, and as a lighter, piano theme in St. George’s Books. Much of the music does an excellent job of bolstering the atmosphere.

The CD version can also be run in SVGA mode – optional for DOS, but mandatory for Windows. In truth, it’s pretty cheap – the icons and character portraits have all been redrawn in the higher resolution, but the backgrounds and sprites have just been resized, so there’s little actual benefit. The Windows version also improperly scales the font, making it look jaggy and ugly. The game is also notoriously buggy, and was hard to get to run on modern PCs for a long time, but thankfully there are some fan made patches and installers available now.

In 2012, Jane Jensen and her husband Robert Holmes turned to Kickstarter to fund a new studio called Pinkerton Road, When successful, it published an original game called Moebius, before following it up with a full remake in Sins of the Father in 2014. Both were co-developed with Phoenix Online Studios, who had previously worked on the King’s Quest fan game The Silver Lining.

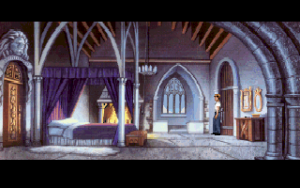

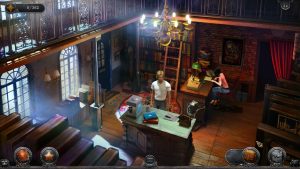

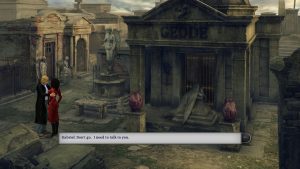

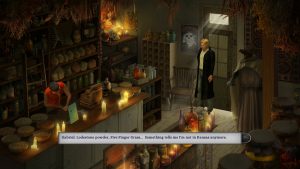

Sins of the Father is a ground up remake, with completely redrawn high resolution 2D backgrounds, polygonal rendered characters, and brand new voice acting. However, it’s obvious that they were working on a limited budget, and while the remake certainly doesn’t look bad, it does often fall into the uncanny valley. The background are routinely gorgeous, but the animations of the character models tend to be robotic. The close-up dialogue portraits looked fine in 2D, but in 3D, with the characters’ dead eyes, it just looks weird.

The masters of the voice acting had been lost, and the sound quality was too poor, plus the team was unable to rehire the original actors, so everything needed to be done from scratch. The replacements did an excellent job, but arguably nothing stands up to the talent from the original. Two exceptions: the narrator is similar to Virginia Capers but speaks much quicker, making her a little more appropriate, and anyone who found Tim Curry’s obviously overdone accent to be painful will probably welcome the new guy. The one aspect that’s unarguably better is the soundtrack. Robert Holmes re-recorded all of the original soundtrack using better quality instrumentation and it all sounds fantastic.

Much of the core of the game remains identical, down to most of the dialogue, but there’s been some tweaks here and there. The game has been restructured a bit so different events occur in different days – for example, in the original you could visit Gabriel’s grandmother at any time, but here you need to wait until the fourth day (despite her still leaving a message for him right at the beginning). A few puzzles and events have changed slightly too, to match up with the Gabriel Knight novel, which Jensen had written a little bit after the game was published. The interface has changed a bit to reduce some of the more redundant commands too.

The goal of the revamp was to expand the audience of the original game, beyond just classic adventure game fans who’d already played the original. To that ends, the game is fairly successful, as a casual audience would be unlikely to find the same faults as a more experience gamer would, and would be less likely to tolerate the original’s popping audio and blurry VGA visuals. But for fans of the original, it ends up redundant – perhaps because the original was so excellent, there’s very little here that makes the remake more attractive, especially the subtle things that reveal its low budget.

Screenshot Comparisons